Abstract

Genetic diversity and population structure of Clarias gariepinus were evaluated by analyzing genetic distances among Sudanese populations and comparing them with reference sequences obtained from GenBank. Pairwise genetic distance (π) estimates indicated substantial variation, ranging from complete genetic identity (π = 0.000) to moderate divergence (π = 0.056). The greatest genetic distance was recorded between the Al-Rahd 2 population and an Indian reference sequence (KX946613), reflecting notable genetic differentiation. Similarly, Al-Rahd 2 exhibited relatively high divergence (π = 0.048) from populations originating in North Korea, Thailand, Congo, Brazil, and Bangladesh, suggesting possible historical isolation, limited gene flow, or distinct evolutionary trajectories. Conversely, several Sudanese populations demonstrated very low to zero genetic divergence when compared with global reference sequences. Abu-Gasba 1, Khashm Al-Girba 3, and Sennar 2 were genetically identical (π = 0.000) to sequences from Egypt and Indonesia. In addition, Abu-Gasba 1 and Khashm Al-Girba 3 showed complete genetic similarity with populations from a broad geographic range, including Nigeria, Ethiopia, Uganda, China, Turkey, Bangladesh, and India. This widespread genetic uniformity suggests strong connectivity and dispersal across regions. A slightly elevated but still minimal genetic distance (π = 0.002) was observed between Khashm Al-Girba 4 and several Asian and African reference populations. The findings reveal a combination of localized genetic differentiation and extensive genetic homogeneity in C. gariepinus, highlighting patterns of dispersal, introduction, and population connectivity.

Keywords:Clarias gariepinus; Population Structure; Genetic divesity; Phylogeney

Introduction

The Nile fauna is rich in fish species [1], including Clarias gariepinus which covers most of the African countries [2]. The taxonomic status of C. gariepinus, in the Sudan, needs to be clarified for better utilization of the fish and identification of a candidate population to develop in aquaculture and exploit on a sustainable manner..

Genetic diversity is a critical measure in fish population studies [3,4], in determining the survival of species and in providing information about the formation of stocks [5]. Recently, molecular tools and techniques were used to refine the taxonomy of some freshwater fish species in Sudan [6-11].

DNA barcoding is a useful and precise identification and characterization tool of species [12]. It has become the technique of choice for identification of fish species, using a short mitochondrial DNA sequence of cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene [13]. A region of the CO1 gene is approved by the Consortium for Barcode of Life (CBOL) for assembling DNA barcodes. This is the only gene sequence currently approved for DNA barcoding [12]. Polymorphic DNA markers provide genetic link to traits of interest useful in identification and in genetic improvement programmes [7]. They also establish relationships with other populations of the same species in other geographical areas [14]; differentiate between species in a specific country [2] and can establish the origin of an introduced species.

The objective of the present work was to study the systematic status of three populations of C. gariepinus from the Nile and one from an inland lake using molecular mitochondrial DNA and to add to the Sudan Gene Bank data.

Material and Methods

Fish specimen

One hundred twenty-three specimens of Clarias gariepinus fish were obtained from 4 sites. Collection sites were Sennar (Blue Nile), Abu-Gasaba (White Nile), Khashm Al Girba (Atbara River) and Al Rahad (an inland lake in the Midwest).

Tissue sampling

Tissue samples from the left pectoral fin and from the second left gill of each specimen were taken and preserved individually in 5.0ml autoclaved plain labeled tubes, and kept in absolute alcohol at -20ºC, as described by [6].

Molecular techniques for identification

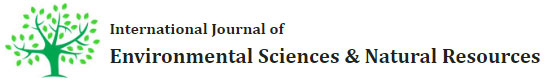

The genomic DNA was extracted from the preserved tissue samples using the Potassium Acetate method following [15]. The PCR amplification was conducted following the procedure described by [16]. The PCR machine (G-STORMA S/N 482-0642) was used to generate the reaction. For the amplification of DNA of C. gariepinus species, two CO1 primers (KF929769F and KF929769R, size and 560bp) were used following [17].

In the initial denaturation step, the contents of the PCR tubes were heated to 95°C for 5 minute to separate the two strands of the template DNA, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 0.3 second. The temperature was decreased rapidly, and the annealing temperature was 60°C for 0.45 seconds. The final step was achieved at 72°C for 1 minute. A final extension cycle was 72°C for 5 minutes, and the machine was programmed to store the reaction at 4°C for 4 minutes until collected. A Nano- Drop (ND-1000) Spectrophotometer Apparatus was used to assess the quality, quantity and the purity of the samples. Gel electrophoresis, using (Bio RAD CE S/N 62S54249), was used to insure the reaction was successful and gave the proper bands which were photographed. The product size was estimated using a 100bp DNA ladder.

Sequencing

For sequencing the best 10 CO1 fragments with proper bands (2 from Sennar, 2 from Abu Gasaba, 2 from Al-Rahd ad 4 from Khashm Al-Girba) were used. The nucleotide sequences obtained were used to search for homology with mitochondrial genes in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, using the BLAST programme to identify the species following [18]. Accession numbers were obtained for the most similar hit with the lowest e-value and highest score. Sequences were visualized using Finch TV Version 1.4.0 and trimming was done using BioEdit version 7.0.3.5.).

NCBI BLAST and BOLD Identification systems analysis

The obtained sequences were blasted to the National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and (Bold systems) to infer the similarity and differences with the global C. gariepinus.

Statistical Analysis

The evolutionary distances were computed using Tamura 3-parameter method described by [19]. Sequence’s analysis was used to model evolutionary rate differences among the four populations with the highest log likelihood. The exploratory search was obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of estimated pairwise distances using the Maximum Likelihood method and Jukes-Cantor model (1969) following [20]. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) were automatically shown next to the branches. There was a total of 447 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA11 [21]. Codon positions included were 1st+2nd+3rd+Noncoding. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. This analysis involved 29 nucleotide sequences. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees following [20].

Results

Molecular analysis results

PCR amplification of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (CO1) gene produced clear and consistent amplicons of approximately 560bp across all individuals from the four sampled populations. All positive samples exhibited identical banding patterns, indicating successful and specific amplification of the target CO1 fragment. No amplification was observed in the negative control, confirming the absence of contamination and the reliability of the PCR assay (Figure 1).

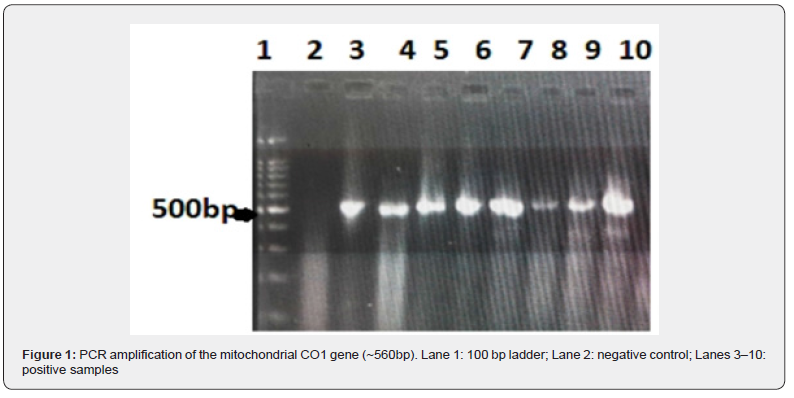

Phylogenetic relationship analysis

A phylogenetic tree was constructed to evaluate the genetic relationship differences among the four population samples (Figure 2). All sequences of C. gariepinus, formed two major clusters. Khashm Al Girba samples cluster separately in one clade. Sennar 2 and Abu- Gasaba 1 formed a sister taxon, and they formed one clade with Abu- Gasaba 3. Sennar 1 and Al-Rahd 2 formed a sister taxon, and together they form one clade with Al-Rahd 1.

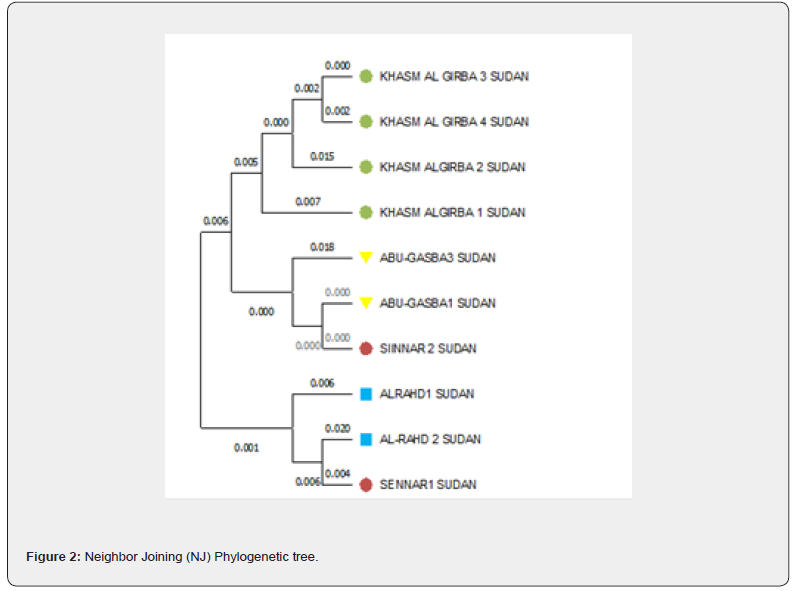

Pairwise genetic distances in native C. gariepinus

In the Sudan, the highest genetic distance (Table 1) was (π = 0.048) between Khashm Al-Girba 2 and Al-Rahad 2, followed by (π = 0.045) between Al-Rahad 2 and Abu-Gassaba 3. The lowest genetic distance was found between Sinnar 2 and from Abu- Gassaba1 sample (π = 0.000).

NCBI BLAST and BOLD identification systems analysis results

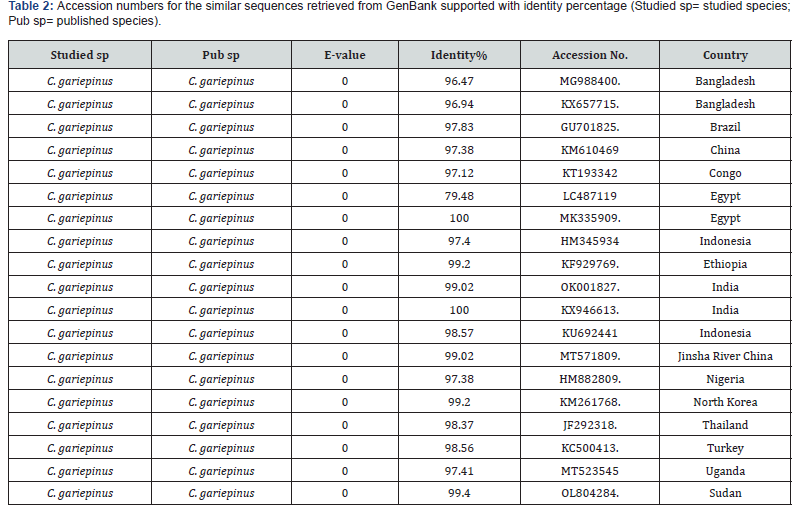

A comparison of 10 studied sequences to infer the similarity and differences with the global C. gariepinus was made. Based on Blasting, NCBI search Bold systems of known identity from GenBank, 19 similar sequences were selected. The values showed that the identity between countries varied between 79.48% and 100% (Table 2).

Global phylogenetic tree analysis with native C. gariepinus

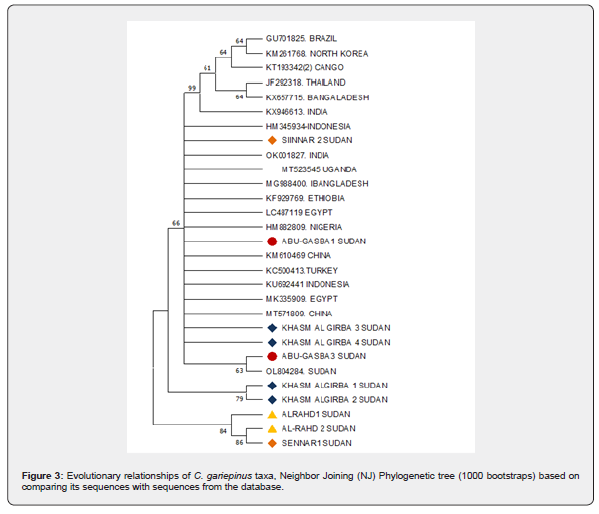

The Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree (Figure 3) of partial mtCO1 C. gariepinus from the four populations was compared with the reference sequences based on Blast, NCBI search of known identity. The GenBank Values at the nodes indicated bootsrap support of 1000 replication. An evolutionary relationships of C. gariepinus using MEGA11 was made. All sequences of C. gariepinus formed two major clusters. Cluster I consisted of the sequences of Abu-Gassaba 3 Sudan sample and reference Ol804284 Atbara River of the Sudan branched as sister taxa from the same node, while, Khashm Al-Girba 3 and 4, Abu-Gassaba 1 and 2, Sennar 2, showed sister taxa with MK335909 and LC487119 Egypt, KU692441 and HM345934 Indonesia, OK001827 India, MT523545 Uganda, MG988400 Bangladesh, KF929769 Ethiopia, HM882809 Nigeria, KM610469 China, KC500413 Turkey, MT571809 China.

However, Cluster II formed C. gariepinus from Sennar 2 and Al-Rahd 2 formed a-sister-taxa, and they formed one clade with Al-Rahd 1. This result from the phylogenetic tree indicated that three of the studied native C. gariepinus populations were closely related to each other than to one of Sennar and the two sequencing from Al-Rahd population.

Global phylogenetic tree analysis with native C. gariepinus

The Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree (Figure 3) of partial mtCO1 C. gariepinus from the four populations was compared with the reference sequences based on Blast, NCBI search of known identity. The GenBank Values at the nodes indicated bootsrap support of 1000 replication. An evolutionary relationships of C. gariepinus using MEGA11 was made. All sequences of C. gariepinus formed two major clusters. Cluster I consisted of the sequences of Abu-Gassaba 3 Sudan sample and reference Ol804284 Atbara River of the Sudan branched as sister taxa from the same node, while, Khashm Al-Girba 3 and 4, Abu-Gassaba 1 and 2, Sennar 2, showed sister taxa with MK335909 and LC487119 Egypt, KU692441 and HM345934 Indonesia, OK001827 India, MT523545 Uganda, MG988400 Bangladesh, KF929769 Ethiopia, HM882809 Nigeria, KM610469 China, KC500413 Turkey, MT571809 China.

However, Cluster II formed C. gariepinus from Sennar 2 and Al-Rahd 2 formed a-sister-taxa, and they formed one clade with Al-Rahd 1. This result from the phylogenetic tree indicated that three of the studied native C. gariepinus populations were closely related to each other than to one of Sennar and the two sequencing from Al-Rahd population.

Global genetic distance of C. gariepinus versus native C. gariepinus

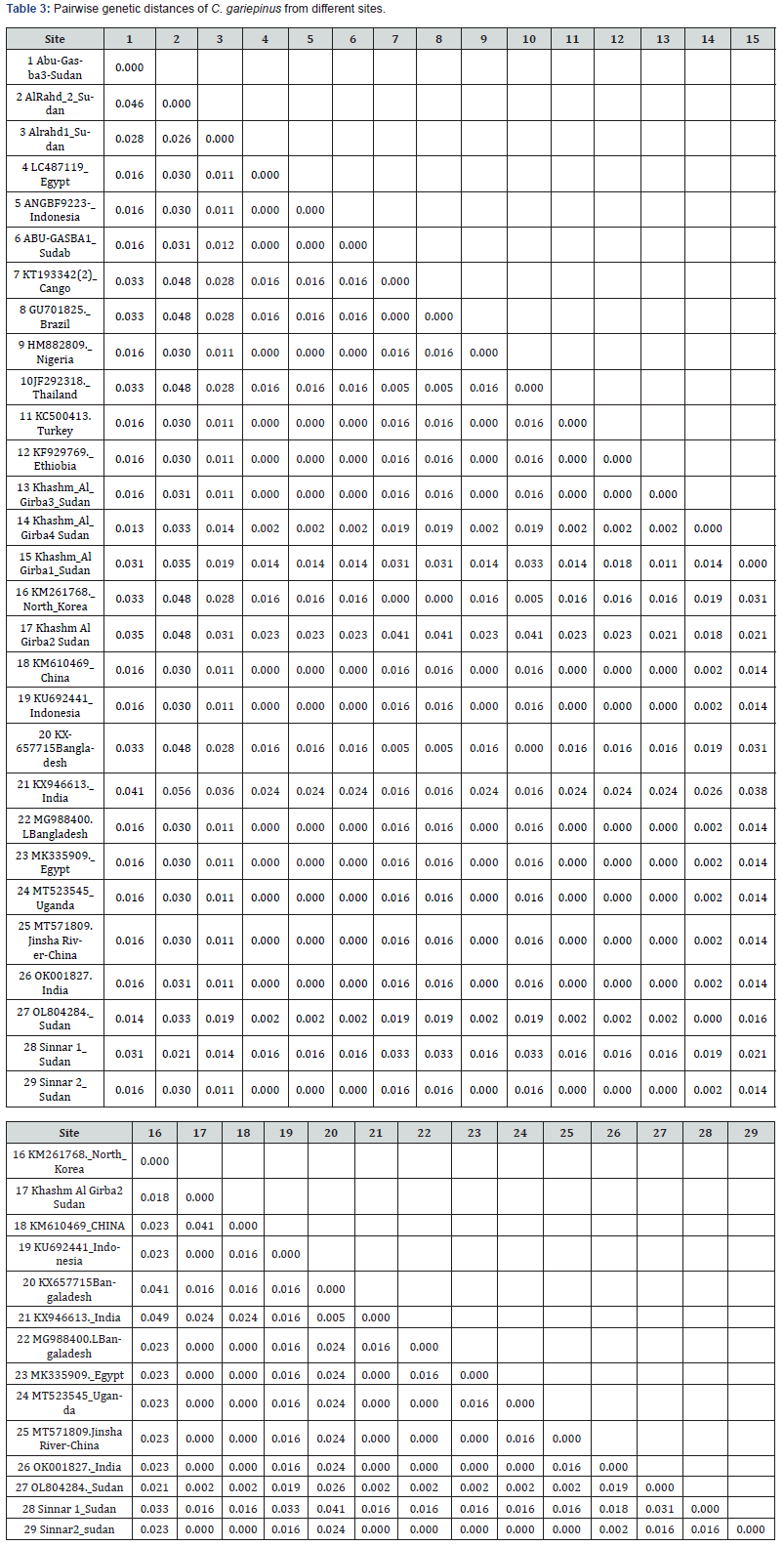

The genetic distance among the analyzed C. gariepinus populations ranged from 0.000 to 0.056 (Table 3). The highest genetic divergence (π = 0.056) was observed between the Al- Rahd 2 population and the reference C. gariepinus sequence from India (GenBank accession KX946613). This was followed by a genetic distance of π = 0.048 between Al-Rahd 2 and sequences from North Korea (KM261768), Thailand (JF292318), Congo (KT193342), Brazil (GU701825), and Bangladesh (KX657715).

In contrast, very low levels of genetic divergence (π = 0.000) were detected between the Sudanese populations Abu-Gasba 1, Khashm Al-Girba 3, and Sennar 2 and reference sequences from Egypt (LC487119) and Indonesia (ANGBF9223). Similarly, Abu- Gasba 1 showed zero genetic distance (π = 0.000) with sequences from Nigeria (HM882809), Turkey (KC500413), Ethiopia (KF929769), Indonesia (KU692441 and ANGBF9223), Bangladesh (MG988400), Egypt (MK335909), Uganda (MT523545), China— Jinsha River (MT571809 and KM610469), and India (OK001827).

Zero genetic divergence (π = 0.000) was also observed between Khashm Al-Girba 3 (Sudan) and sequences from Bangladesh (MG988400), Egypt (MK335909), Nigeria (HM882809), Uganda (MT523545), China—Jinsha River (MT571809 and KM610469), India (OK001827), Indonesia (KU692441), and Turkey (KC500413).

A slightly higher genetic distance (π = 0.002) was recorded between Khashm Al-Girba 4 (Sudan) and reference sequences from China (KM610469), Bangladesh (MG988400), Egypt (MK335909), Indonesia (ANGBF9223), Nigeria (HM882809), and Uganda (MT523545).

Discussion

In terms of abundance and economic importance, C. gariepinus is the second most common and widely distributed freshwater fish species in the Sudan [22,23]. The present study aimed to contribute to C. gariepinus taxonomy and add to its molecular biology using PCR. It indicated that the four populations belong to one species. The sequences of the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) mitochondrial gene are extensively used to determine inter and intra species relationships and to draw their evolutionary trees [11,24,25].

Sequences of CO1 was used in this study to draw the phylogenetic tree to allow for comparison of the results with similar studies retrieved from GenBank database showed that the interspecies genetic divergence based on the substitution pattern ranged from 0.000 to 0.056 for the COI gene. This indicates that the native C. gariepinus are closely related with most of the reference groups. It seems that C. gariepinus originated from Africa, and due its high environmental tolerability it spread to almost all continents and gaining popularity in aquaculture [26]. According to [27] in Brazil and since its market interest was low, the species was used as sport fish. They reported that uncontrolled escapes happened and the fish propagated to the Amazon River branches and lakes and became the top invader there. Molecular genetics was used to follow the origin and movement of the C. gariepinus out of Africa [4,14,28,29]. The phylogenetic results drawn by [28], showed that C. gariepinus from Africa, Asia and Turkey are closely related. None of the Sudanese studied individuals was found closely related to GU701825 from Brazil, KX657715 from Bangladesh, KX946613 from India, KM261768 from North Korea, JF292318 from Thailand and KT193342 from Congo. The results indicated that the variation in this species is very wide internationally.

The phylogeny analyses identified identical groups between native Khashm Al-Girba 3 and 4, Abu-Gassaba 1 and Sennar 2 and most of the members of the two groups from the Genbank. The first group, a reference of African Sudanese C. gariepinus, mainly clustered with Uganda, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Egypt. The second one related to a reference of Asian C. gariepinus found in Thailand, China, Bangladesh, India and Indonesia. All these groups were closely related to each other and derived from the same clade. The sequences of Abu-Gassaba 3 Sudan sample and Ol804284 Sudan retrieved from genbank branched as sister taxon from the same node. Sennar 2 is showing the greatest diversion from the most of the native C. gariepinus.

Another important aspect in the population genetics of C. gariepinus is its capacity to hybridize with other species from the same genus, or with other genera belonging to its family [30,31]. Some of these hybrids are well-known to grow faster than the parent native species [32-35]. Some cases of escapes from farms [27] of these hybrids to the wild were recorded. This may cause some degree of genetic introgression and hence possible changes on the distribution of different conservation units of C. gariepinus in the wild as normally expected by preference to certain environmental conditions over the others.

Conclusion

The findings showed that the populations of C. gariepinus are phenotypically the same. The native C. gariepinus fish populations are closely related with most of the reference groups reported from Africa and Asia. The bioinformatics analyses of phylogenetic trees, and the median joining network data show a close proximity between the Sudanese C. gariepinus samples and the Indonesian ones.

Ethics: Ethics approval and consent to participate, human and animal rights, consent for publication and availability of data and material are not applicable.

Funding Statement by: The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research supported the field workk at Sinnar and Al Rahadl.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Acknowledgement

Mr. Mutasim Yousif, Director of Fisheries Reteach Centre of Khashm El-Girba, provided C. gariepinus from Khashm El Girbara. AI was used to verify reference digital object identifier (DOI) and uniform resource locator (URL).

References

- Neumann D, Obermaier H, Morti ZT (2016) Annotated checklist for fishes or the Main Nile Basin in the Sudan and Egypt based on recent specimenrecord (2006-2015). Cybium 40(4): 287-317.

- Van Steenberge MW, Vanhove MP, Chocha M, Larmuseau MH, Swart BL, et al. (2020) Unravelling the evolution of Africa's drainage basins through a widespread freshwater fish, the African sharptooth catfish Clarias gariepinus. Journal of Biogeography 47(8): 1739-1754.

- Kirk H, Freeland JR (2011) Applications and Implications of Neutral versus Non-neutral Markers in Molecular Ecology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 12(6): 3966-3988.

- Abdul-Muneer PM (2014) Application of Microsatellite Markers in Conservation Genetis and Fisheries Management: Recent Advances in Population Structure Analysis and Conservation Strategies. In: NA Doggett (Ed.), Genetics Research International 2014.

- Elberri AL, Galal-Khallaf A, Gibreel SE, El-Sakhawy SF, El-Garawani, et al (2020) DNA and eDNA-based tracking of the North African sharptooth catfish Clarias gariepinus. Molecular and cellular probes 51: 101535.

- Ebraheem HA (2012) Morphometrics, Meristics and Molecular Characterization of Oreochromis niloticus, Sarotherodon galilaeus and Tilapia zilli (Cichlidae) from Kosti, Sennar, Khashm El Girba and Al Sabloga. M. Sc. Thesis, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Khartoum, Sudan, 2012.

- Mohammed ATM, Mahmoud ZN, Abushama HM (2019) Morphometric Measurements, Meristic Counts, and Molecular Identification of Alestes dentex, Alestes baremoze, Brycinus nurse, and Brycinus macrolepidotus from the River Nile at Kreima. The Open Biology Journal 7: 25-38.

- Ahmed EY, Hamid MM, Mahmoud ZN, Hagar EA, Masri MA (2020) Meristic, morphological and genetic identification of the fish Brycinus nurse (Alestidae) from Sennar, Blue Nile. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 8(4): 373-376

- Omer OM, Abdalla HA, Mahmoud ZN (2020) Genetic Diversity of Two Tilapia Species (Oreochromis niloticus and Sarthrodon galilaeus) Using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA. The Open Biology Journal 7: 3-9.

- Hassan HA, Mahmoud ZN, Abukashawa SMA (2021) Molecular Characterization of Oreochromis niloticus, Sarotherodon galilaeus and Coptodon zillii (Cichlidae) from Kosti, Sennar, Khashm El Girba and Al Sabloga. In: Dr. Aditya Gupta (Ed.), Latest trends in Fisheries and Aquatic Animal Health (Volume 2). Published by AkiNik Publication. ISBN Number: 978-93-90541-67-6.

- Abd Alrasoul EYA (2023) Meristic Morphological and Molecular identification of Eletric Catfish (Malapterurus electricus) from Sudan, with a description of a Subspecies. M. Sc. Thesis, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Khartoum.

- Hubert N, Hanner R, Holm E, Mandrak NE, Taylor E, et al. (2008) Identifying Canadian freshwater fishes through DNA barcodes. PLoS ONE 3(6): e2490.

- Lakra WS, Singh M, Goswami M, Gopalakrishnan A, Lal KK, et al. (2016) DNA barcoding Indian freshwater fishes. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27(6): 4510-4517.

- Behmene IE, Bachir BB, Homrani A, Daoudi M, Vazquez FJS, et al. (2020) Morphometric and genetic diversity of an African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) population from Southeast Algeria. African Journal of Ecology 60(4): 1287-1292.

- Ghossein RA, Ross DG, Salomon RN, Rabson AR (1994) A search for mycobacterial DNA in sarcoidosis using the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Clin Pathol 101(6): 733-737.

- Dinesh KR, Lim TM, Chan WK, Phang VP (1996) Genetic variation inferred from RAPD fingerprinting in the three species of tilapia. Aquacult Int 4: 19-30.

- Folmer O, Hoeh WR, Black MB, Vrijenhoek RC (1994) Conserved primers for PCR amplification of mitochondrial DNA from different invertebrate phyla. Molec Mari Biol Biotech 3(5): 294-299.

- http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi.

- Tamura K (1992) Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G+C-content biases. Molecular Biology and Evolution 9(4): 678-687.

- Tamura K, Nei M (1993) Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 10(3): 512-526.

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S (2021) MEGA 11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38(7): 3022-3027.

- Hagar EA (2017) Growth and quality of the catfish Clarias gariepinus Cultured in Backyard. Ph. D. Thesis, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Khartoum.

- Mahmoud HHY (2018) On the Quality of Clarias gariepinus from Turdat El Rahad, North Kordofan State. M. Sc. Thesis. Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Khartoum.

- Abbas EM, Soliman T, El-Magd MA, Kato M. et al (2017) Phylogeny and DNA barcoding of the family Sparidae inferred from mitochondrial DNA of the Egyptian waters. J Fish Aquat Sci 12(2): 73-81.

- Parvez I, Rumi RA, Ray PR, Pradit S, Ray PR, et al. (2022) Invasion of African Clarias gariepinus Drives Genetic Erosion of the Indigenous batrachus in Bangladesh. Biology 11(2): 252.

- Clarias gariepinus. Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme. In: Pouomogne V (Ed.), Fisheries and Aquaculture. Rome.

- Vitule JR, Umbria SC, Aranha JMR (2006) Invasion note: Introduction of the African catfish Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) into Southern Brazil. Biological Invasions 8: 677-681.

- Geba KM (2015) North African sharptooth catfish Clarias gariepinus in silico analyses. Journal of Bioscience and Applied Research 1(4): 184-191.

- Ola-Oladimeji F (2021) Population genetics of fast-and slow-growing strains of Clarias gariepinus (Osteichthyes: Clariidae) as revealed by microsatellite markers. Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisherie 25(2): 21-35.

- Sobczak M, Panicz R, Sadowski J, Polgesek M, Kujawska JZ, et al. (2022) Does Production of Clarias gariepinus × Heterobranchus longifilis Hybrids Influence Quality Attributes of Fillets? Food 11(4): 2074.

- Yi Y, Lin CK, Diana JS (2003) Hybrid catfish (Clarias macrocephalus x gariepinus) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) culture in an integrated pen-cum-pond system: growth performance and nutrient budgets. Aquaculture 17(1-4): 395-408.

- Teugels GG, Ozouf-costz C, Legendre M, Parrent M (1992) A karyological analysis of the artificial hybridization between Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) and Heterobranchus longifilis Valenciennes, 1840 (Pisces; Clariidae). Journal of Fish Biology 40(1): 81-86.

- Adeyemo AA, Oladosu GA, Ayinla AO (1994) Growth and survival of fry of African catfish species, Clarias gariepinus Burchell, Heterobranchus bidorsalis Geoffery and Heteroclariasreared on Moina dubia in comparison with other first feed sources. Aquaculture 119(1): 41-45.

- Na-Nakorn U, Kamonrat W, Ngamsiri T (2004) Genetic diversity of walking catfish, Clarias macrocephalus, in Thailand and evidence of genetic introgression from introduced farmed gariepinus. Aquaculture 240(1-4): 145-163.

- Tiogue CT, Nyadjeu P, Mouokeu R, Tekou G, Tchoupou H (2020) Catfishes (Siluriformes, Clariidae): Exotic (Clarias gariepinus Burchell, 1822) and Native (Clarias jaensis Boulenger, 1909) Species under Controlled Hatchery Conditions in Cameroon. Advances in Agriculture.