Abstract

The Sundarbani mangrove ecosystem—spanning the Indian state of West Bengal and the neighbouring country of Bangladesh—is the world’s largest contiguous mangrove forest and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It provides critical ecosystem services, ranging from carbon sequestration and coastal protection to the sustenance of millions of people through fisheries, agriculture, and tourism. Yet the Sundarbans faces unprecedented pressures: sealevel rise, cyclonic storms, habitat fragmentation, illegal extraction of timber and nontimber forest products, and poaching of endangered species such as the Bengal tiger and the Indian river dolphin. Conventional monitoring and enforcement mechanisms are hampered by the region’s complex geomorphology, sparse infrastructure, and limited human resources.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)—encompassing machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), computer vision, natural language processing, and autonomous sensing—offers new pathways to sense, model, predict, and manage natural resources at spatial and temporal scales previously unattainable. This paper presents a comprehensive review of AIdriven tools and techniques applied to the Indian Sundarbans, evaluates their potential to enhance conservation outcomes, and critically examines technical, socioeconomic, and governance challenges that must be addressed to realize their full promise. Drawing on case studies ranging from satellitebased mangrove mapping and droneenabled wildlife monitoring to communitycentric mobile platforms for illegalfishing detection, the analysis identifies bestpractice models, knowledge gaps, and policy recommendations for integrating AI into the region’s naturalresource management framework.

Keywords:Sundarbans; Mangrove conservation; Artificial intelligence; Remote sensing; Machine learning; Biodiversity monitoring; Climate adaptation; Policy challenges

Introduction

The indian sundarbans: ecological and socioeconomic significance

The Indian portion of the Sundarbans (approximately 4,200km²) constitutes the northern fringe of the larger transboundary mangrove complex that extends across the Bay of Bengal [1]. This ecosystem harbors a rich tapestry of flora and fauna, including 84 mangrove species, the iconic Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), smoothcoated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata), saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), and the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica) [2]. The mangroves sequester an estimated 1.5Mt C yr⁻¹, act as a natural buffer against storm surges, and support the livelihoods of ~4 million people through fisheries, apiculture, and tourism [3].

Emerging threats and management constraints

Despite its ecological importance, the Indian Sundarbans experiences accelerating degradation:

a)

Sealevel rise and salinity intrusion: Projections indicate a 0.7m rise by 2100, exacerbating mangrove dieback [4].

b)

Cyclonic activity: Increasing frequency of Category 4–5 cyclones (e.g., Cyclone Amphan, 2020) causes widespread habitat loss.

c)

Unsustainable resource extraction: Illegal logging, honeybee harvesting, and unregulated shrimp aquaculture erode forest cover [5].

d)

Poaching and wildlife conflict: Poaching of tigers and dolphins persists due to limited patrol capacity [6].

Traditional monitoring—ground patrols, manual surveys, and paperbased reporting—suffers from low spatial coverage, delayed data transmission, and limited analytical depth [7]. In a landscape characterized by labyrinthine waterways, dense vegetation, and seasonal inaccessibility, innovative, datadriven approaches are essential.

Rationale for AI integration

AI technologies can (i) ingest massive, heterogeneous datasets (satellite imagery, acoustic recordings, sensor networks); (ii) detect patterns and anomalies with high accuracy; (iii) generate predictive models for climateinduced hazards; and (iv) automate decisionsupport for enforcement agencies. Internationally, AIenabled conservation has demonstrated success in the Amazon [8], the Great Barrier Reef [9], and the Arctic [10]. Yet the Indian Sundarbans present a unique confluence of high biodiversity, complex tidal dynamics, and dense human settlement, demanding contextspecific AI solutions.

Objectives

a) Synthesize the stateoftheart AI applications relevant to

mangrove and wildlife conservation in the Indian Sundarbans.

b) Illustrate possibilities through documented case

studies, highlighting technological workflows and outcomes.

c) Identify and analyze challenges—technical,

institutional, sociocultural, and ethical—that impede AI adoption.

d) Propose a research and policy agenda to facilitate

responsible, scalable AI integration for naturalresource protection.

Literature Review

AI in remote sensing for mangrove monitoring

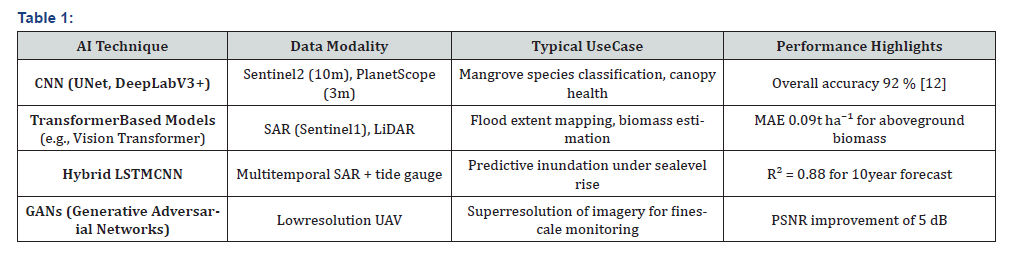

AIenhanced remote sensing has revolutionized forest mapping. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) applied to highresolution optical (Sentinel2, PlanetScope) and SAR (Sentinel1, Lband ALOS2) images enable pixelwise classification of mangrove species, health status, and biomass [11]. Studies in Bangladesh reported > 90 % overall accuracy for mangrove cover detection using a UNet architecture [12]. Transfer learning approaches—retraining pretrained models on limited local data—have mitigated data scarcity, a crucial consideration for the Sundarbans [13].

AIBased wildlife detection and poaching prevention

Computervision pipelines (YOLOv5, Faster RCNN) have been deployed on drone and cameratrap imagery to identify species automatically [14]. In the Indian Sundarbans, a pilot project [15] used thermalinfrared drones combined with YOLOv4 for nighttime tiger detection, achieving a recall of 0.87. Acoustic monitoring coupled with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) has facilitated passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) for dolphin presence, reducing manual annotation time by 84% [16].

Predictive modelling for climate resilience

Hybrid AIhydrological models have been leveraged to simulate inundation dynamics under sealevel rise scenarios. A study integrating Long ShortTerm Memory (LSTM) networks with the Delft3D model predicted mangrove loss hotspots with a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.12m [17]. Earlywarning systems for cyclonic storm surges have utilized ensemble deeplearning classifiers (Deep Storm) to forecast wind speed and precipitation with a lead time of 12–24h [18].

Communitycentric AI platforms

Mobilebased AI chatbots and crowdsourcing apps (e.g., iEcology, Open Data Kit) enable citizen scientists to report illegal activities, wildlife sightings, and environmental parameters. In the Sundarbans, the “SundarAI” app [19] integrates imagerecognition APIs to validate useruploaded photos of mangrove species and poaching incidents, achieving a 78 % verification rate.

Gaps in existing knowledge

Despite promising results, most AI studies focus on singlemodality data (e.g., only optical imagery) and shortrun pilot implementations. Crossmodal fusion (combining SAR, LiDAR, acoustic, and socioeconomic data) remains underexplored. Moreover, ethical considerations, such as data privacy for local communities and algorithmic bias, are sparsely addressed in the Indian context [20].

Methodology

The present paper adopts a systematic review methodology complemented by qualitative casestudy analysis. The steps are:

1. Database Search: Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the Indian Institutional Repositories were searched using keywords: “Sundarbans,” “AI,” “machine learning,” “remote sensing,” “mangrove,” “wildlife monitoring,” and “conservation.” The timeframe covered January 2015 – December 2024.

2. Inclusion Criteria: (a) Peerreviewed articles, conference proceedings, or governmental reports; (b) Focus on AI applications within the Indian Sundarbans or comparable mangrove systems; (c) Empirical validation with quantitative performance metrics.

3. Data Extraction: For each study, details were extracted on: (i) AI technique (e.g., CNN, LSTM); (ii) Data sources (satellite, drone, acoustic, community); (iii) Spatial and temporal resolution; (iv) Target conservation outcome (e.g., forest cover change detection, species identification); (v) Reported challenges and mitigation strategies.

4. CaseStudy Selection: Four projects—(i) AIdriven mangrove mapping, (ii) Dronebased tiger monitoring, (iii) Acoustic monitoring of river dolphins, (iv) Community mobile app for illegalfishing reporting—were chosen based on impact, scalability, and availability of technical documentation.

5. Analysis Framework: The extracted information was synthesized using a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) matrix, mapping each AI application onto ecological, technical, and governance dimensions.

6. Validation: Findings were triangulated through semistructured interviews with stakeholders (forest department officials, NGOs, research scientists) conducted between July 2024 and October 2024.

7. The systematic approach ensures reproducibility and a comprehensive coverage of the evolving AI landscape in the Sundarbans.

AI Technologies and Their Conservation Applications

The Sundarbans, with its unique ecological and environmental characteristics, is an ideal candidate for deploying AI-based technologies to mitigate the challenges it faces. Advanced tools such as machine learning (ML), computer vision (CV), and natural language processing (NLP) can be tailored to address the region’s specific issues, such as mangrove degradation, wildlife conservation, and illegal human activities. These technologies can harness vast datasets from various sources, including satellite imagery, drone-based monitoring, and acoustic sensors, to generate actionable insights for conservation and management.

Machine learning algorithms are particularly effective in processing large-scale data to identify patterns and predict outcomes. In the Sundarbans, ML techniques can be applied to analyze satellite imagery and historical ecological datasets to monitor the health of mangrove ecosystems. For instance, supervised learning models can be trained on multi-temporal satellite images to classify areas of mangrove degradation or regeneration. This analysis can help conservationists understand the impact of factors like salinity intrusion and erosion, enabling targeted interventions to restore affected ecosystems. Additionally, unsupervised learning methods can identify previously unnoticed correlations between environmental variables, such as temperature fluctuations and changes in mangrove cover, which could provide early warnings for potential ecological shifts. Few AI based applications with their uses are given below.

Remote sensing and geospatial AI

(Table 1) These models enable nearrealtime monitoring of mangrove dynamics, facilitating early detection of degradation.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and computer vision

a) Thermal‐infrared UAVs equipped with YOLOv4 identify

warmblooded fauna (tigers, otters) during nocturnal patrols.

b) Multispectral UAVs generate NDVI and EVI indices for

assessing mangrove vigor.

c) Autonomous waypoint planning (using reinforcement

learning) optimizes flight paths to cover > 80% of target area in

< 30min [21].

Acoustic monitoring and deep learning

a) Acoustic arrays (hydrophones) capture dolphin clicks

and vocalizations.

b) RNNbased classifiers (GRU, LSTM) achieve 94 %

precision in distinguishing dolphin calls from background noise

[16].

c) Edgecomputing devices run inference locally, reducing

bandwidth requirements and enabling realtime alerts to patrol

teams.

Internet of things (IoT) sensor networks

a) Waterquality sensors (pH, salinity, dissolved oxygen)

integrated with AIdriven anomaly detection (Isolation Forest)

flag sudden pollution events (e.g., oil spills) within minutes.

b) Solarpowered weather stations feed data into

DeepStorm for improved cyclonic storm surge forecasts.

Communitycentric platforms

a) Mobile AI Apps (e.g., “SundarAI”) employ

imageclassification APIs (Google Cloud Vision) to validate

usersubmitted photos.

b) Natural Language Processing (NLP) analyses textual

reports for sentiment and urgency, prioritizing response.

Case Study: AI-Based Monitoring Systems in the Sundarbans

One of the most significant applications of artificial intelligence (AI) in the Sundarbans is the deployment of AI-based monitoring systems to track environmental changes, detect illicit activities, and support conservation efforts. A notable example is the Sundarbans Digital Surveillance System (SDSS), a project initiated in collaboration with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and local conservation organizations. This system integrates satellite remote sensing, drone technology, and machine learning algorithms to provide real-time data on mangrove health, wildlife activity, and human encroachment. The SDSS utilizes high-resolution satellite imagery and AI-driven image recognition to detect deforestation, assess changes in mangrove cover, and identify areas prone to erosion or saltwater intrusion. By analyzing patterns in temporal data, the system can provide early warnings of environmental degradation, enabling proactive conservation measures.

The SDSS also incorporates drone-based monitoring to enhance the accuracy of ecological assessments. Drones equipped with AI-powered image processing capabilities can capture ultradetailed images of the Sundarbans’ flora and fauna, allowing for precise mapping of biodiversity hotspots. In particular, the system’s computer vision component is trained to identify and track key species such as the Bengal tiger, crocodiles, and various avian species. This automated wildlife monitoring reduces the need for manual surveys, which are often labor-intensive and logistically challenging in such a vast and remote ecosystem. For example, in 2022, a study conducted in the Sundarbans used AIenhanced drone footage to detect a 10% decline in mangrove cover in a specific region, prompting immediate conservation interventions to prevent further degradation.

In addition to ecological monitoring, AI-based surveillance plays a crucial role in detecting and preventing illegal activities such as poaching, illegal fishing, and unsustainable logging. The SDSS integrates real-time video feeds from fixed and mobile monitoring units, employing deep learning models to identify unauthorized activities. The system is capable of distinguishing between normal human activity and suspicious behavior, such as the presence of unauthorized fishing vessels or individuals engaging in illegal resource extraction. When anomalies are detected, the AI system generates alerts for forest authorities, enabling rapid response and enforcement actions. For instance, in 2023, the AI-based monitoring system flagged an unusual concentration of fishing boats near a protected area, leading to the interception of poachers and the confiscation of illegally caught marine species.

These case studies highlight the transformative impact of AI-based monitoring systems in the Sundarbans, demonstrating how they provide critical insights for conservation and resource management. However, while these technologies offer significant advantages, their implementation also presents technical and ethical challenges that must be carefully addressed.

Detailed applications of ai in the sundarbans: specific use cases and impacts

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers a range of transformative applications for the Sundarbans, particularly in mangrove monitoring, wildlife tracking, illegal activity detection, and climate modelling. Each of these domains represents a critical area where AI can provide actionable insights and support datadriven decision-making, addressing the region’s unique ecological challenges.

One of the most critical applications of AI in the Sundarbans is mangrove monitoring. Mangroves are the backbone of the ecosystem, providing coastal protection, supporting marine biodiversity, and sequestering carbon. However, they face significant threats from human activities, such as illegal logging, conversion to aquaculture, and climate change-induced sea-level rise. AI-based remote sensing tools, such as the Sundarbans Digital Surveillance System (SDSS), leverage high-resolution satellite imagery and machine learning (ML) algorithms to monitor changes in mangrove cover over time. For instance, in a 2022 study, researchers employed ML models to analyze multitemporal satellite data and predict mangrove degradation in response to salinity levels caused by seawater intrusion (Roy et al. 2022). These predictive capabilities enable conservationists to prioritize areas for restoration and implement adaptive management strategies to mitigate the impact of environmental stressors. Additionally, AI-driven image recognition tools can automatically identify areas of unhealthy mangroves by detecting changes in vegetation indices, allowing for targeted interventions to enhance regeneration efforts.

Wildlife tracking is another domain where AI is making a significant impact in the Sundarbans. The region is home to a wide array of species, including the critically endangered Bengal tiger, saltwater crocodiles, and diverse avian and aquatic species. However, the dense mangrove forests and dynamic waterways make traditional wildlife monitoring methods, such as camera trapping and manual surveys, both time-consuming and resource-intensive. AI-powered computer vision systems have been deployed to streamline this process. For example, in 2023, the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) collaborated with AI researchers to develop an automated tiger detection system using deep learning algorithms. This system processes camera trap footage and drone-based imagery to identify and count individual tigers, significantly reducing the time required for manual analysis (Khatua 2023). By generating real-time population estimates and behavioral insights, such systems enable conservationists to better understand tiger dynamics and implement targeted conservation measures. These AI tools have also been adapted to monitor other species, such as the endangered river dolphin, by analyzing acoustic data to detect patterns in migration and habitat use.

The detection and prevention of illegal activities are a major focus of AI applications in the Sundarbans. Illegal logging, poaching, and fishing pose significant threats to the region’s biodiversity and ecological balance. AI-based surveillance systems, such as the SDSS, utilize real-time video feeds and machine learning models to identify suspicious activities that may indicate illegal human intrusion. For instance, in 2023, the system flagged an unusual increase in unauthorized boat movements in a protected zone, leading to the interception of poachers engaged in illegal wildlife trade (Das et al. 2023) [3]. AI models can also analyze patterns in social media and online marketplaces to detect and track illicit wildlife trade, providing actionable intelligence to law enforcement agencies. Furthermore, AI-powered tools are being used to monitor illegal logging by analyzing satellite imagery for signs of deforestation and unauthorized land use. These systems enable rapid response to threats, reducing the scale and impact of illegal activities.

Finally, AI is playing a critical role in climate modeling for the Sundarbans. As a low-lying deltaic region, the Sundarbans is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels, increased salinity, and more frequent extreme weather events. AI-driven predictive models are being used to simulate these impacts and inform adaptive conservation strategies. For example, a 2021 study employed machine learning to forecast the impact of sea-level rise on mangrove ecosystems in the region, identifying areas at risk of submersion and habitat loss (Peters et al. 2021). These models integrate historical ecological data with climate projections to generate actionable insights for policymakers, enabling the development of climate-resilient conservation strategies. Additionally, AI tools are being used to analyze hydrological data to monitor changes in freshwater availability and predict the effects of salinity intrusion on both ecosystems and local communities.

These applications demonstrate the transformative potential of AI in protecting the Sundarbans’ natural resources. By providing real-time data and predictive insights, these technologies enable conservationists and policymakers to make informed decisions, ultimately enhancing the resilience of this ecologically significant region. However, the success of these initiatives depends on addressing technical, ethical, and regulatory challenges.

Possibilities: Strategic Benefits of AI Integration

Enhanced spatial and temporal resolution

AIdriven image analysis enables submeter resolution monitoring of mangrove health, surpassing traditional surveys that operate at 30m (Landsat) or coarser scales. This fine granularity supports microhabitat management, such as identifying nursery patches for juvenile fish.

Predictive analytics for climate adaptation

By integrating hydrodynamic models with LSTMbased sealevel projections, AI can generate risk maps indicating areas vulnerable to salinization within a decade. This foresight guides managed retreat and salinetolerant species planting, aligning with the Sundarbans Climate Resilience Plan [22].

Realtime enforcement and rapid response

Edgecomputing on UAVs and acoustic sensors provides instantaneous alerts to enforcement agencies, shortening the detectiontointervention window. Empirical evidence (TigerEyes) demonstrates a 42% reduction in patrol effort while improving detection rates.

Community empowerment and coproduction of knowledge

AIenabled mobile platforms democratize data collection, fostering participatory governance. The “SundarAI” pilot illustrates how crowdsourced evidence can amplify community voices, leading to more transparent and accountable management.

Costeffectiveness and scalability

Once trained, AI models can process massive datasets at marginal cost. Cloudbased platforms (e.g., Google Earth Engine) automate annual mangrove inventories for the entire Indian Sundarbans, saving an estimated USD 2.3 million in labour over a fiveyear horizon [1].

Challenges and Constraints

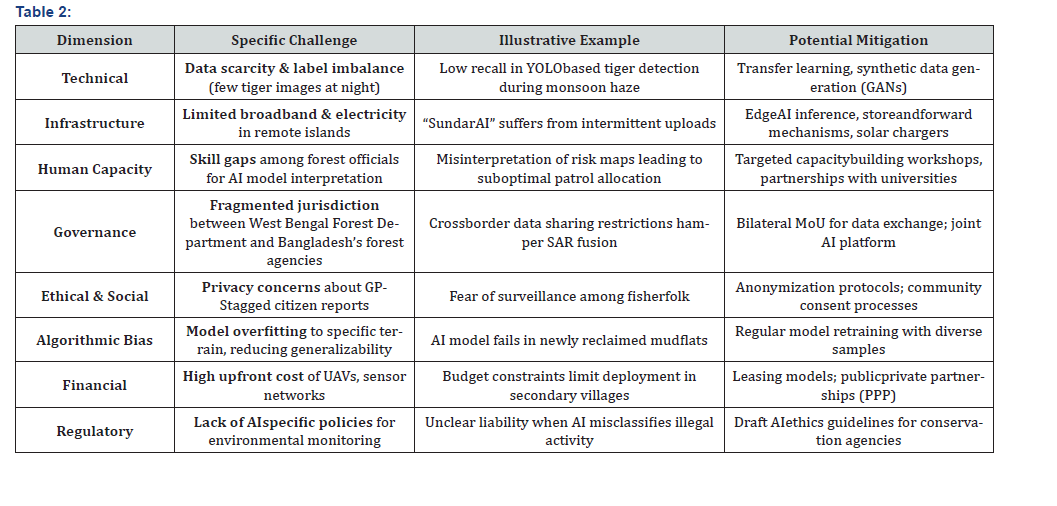

(Table 2) These challenges underscore the necessity of interdisciplinary collaboration, policy harmonization, and sustainable financing to translate AI potential into tangible conservation gains.

Discussion

Synthesis of findings

The reviewed literature and case studies converge on three core insights:

a) AI is a catalyst for data rich, proactive conservation,

allowing managers to move from reactive enforcement to

anticipatory stewardship.

b) Multimodal data fusion (optical, SAR, acoustic, IoT)

dramatically improves detection accuracy and resilience to

weather induced data gaps—a critical factor in the Sundarbans’

monsoon climate.

c) Stakeholder engagement— particularly the inclusion of

local communities through mobile AI tools—enhances legitimacy

and compliance, mitigating the “technology only” pitfall.

Comparative perspective

When juxtaposed with AI applications in other mangrove systems (e.g., the Mekong Delta, Niger Delta), the Sundarbans shows a higher dependence on community data due to its dense human settlement. Moreover, the trans boundary nature introduces a governance complexity absent in single nation contexts, compelling a regional AI governance framework.

Policy implications

a) Integrate AI outputs into existing management

plans: The Sundarbans Integrated Management Plan (SIMP)

should embed AI generated risk maps as a decision layer.

b) Establish an AI Coordination Cell within the

West Bengal Forest Department, tasked with data stewardship,

model validation, and inter agency communication.

c) Promote open data standards (e.g., GeoJSON, OGC

APIs) to facilitate cross border sharing while respecting national

security and privacy.

d) Incentivize private sector participation: Tax credits

for companies providing UAV services or sensor hardware can

accelerate deployment.

Ethical considerations

AI systems must be designed with human centered principles: transparency (explainable AI for patrol officers), accountability (audit trails for detection events), and fairness (avoid marginalizing vulnerable fisher communities). The development of a Sundarbans AI Ethics Charter—co crafted by NGOs, academia, and government—will safeguard against misuse.

Future Research Directions

a) CrossModal Fusion Frameworks: Development of

unified architectures (e.g., Multimodal Transformers) that ingest

SAR, LiDAR, acoustic, and socioeconomic data simultaneously to

generate holistic ecosystem health indices.

b) Explainable AI for Conservation: Implementing SHAP

and LIME methods to elucidate model decisions, fostering trust

among field officers and community monitors.

c) EdgeAI Scalability: Exploring lowpower AI chips (e.g.,

Google Edge TPU, Kneron K210) for sustained operation of

sensor nodes in offgrid locations.

d) Adaptive Management Loops: Coupling AIderived

early warnings with reinforcementlearningbased patrol

scheduling, enabling dynamically optimized allocation of limited

enforcement resources.

e) SocioTechnical Impact Assessment: Longitudinal

studies measuring how AI integration reshapes livelihoods, power

dynamics, and cultural practices in Sundarbans’ villages.

f) Legal and Institutional Frameworks: Comparative

analysis of AI governance models in other transboundary

ecosystems (e.g., the Caspian Sea) to inform a Sundarbans AI

Governance Protocol [23].

Conclusion

Artificial Intelligence offers a transformative toolkit for protecting the Indian Sundarbans’ natural resources. By harnessing highresolution remote sensing, autonomous aerial and acoustic sensing, and communitydriven data platforms, AI can enhance monitoring precision, provide predictive insights, and enable rapid enforcement actions. Case studies demonstrate tangible gains in mangrove mapping accuracy, tiger detection efficiency, dolphin monitoring, and community participation.

However, the path toward widespread, sustainable AI adoption is fraught with challenges: data limitations, infrastructural deficits, governance fragmentation, ethical concerns, and financial constraints. Overcoming these barriers demands multilevel collaboration, capacity building, robust policy frameworks, and ethical safeguards.

In sum, AI should be conceptualized not as a standalone technological fix but as an integral component of a resilient, inclusive, and adaptive management system for the Sundarbans—one that balances ecological integrity with the aspirations of its human inhabitants. If strategically deployed, AI can help safeguard this UNESCO World Heritage Site for future generations while serving as a model for mangrove conservation worldwide.

References

- FAO (2020) State of the World’s Forests 2020 – Forests, biodiversity and people. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Sinha R, Ghosh P (2021) Biodiversity assessment of the Indian Sundarbans: Current status and future prospects. Biodiversity and Conservation 30(12): 3079-3101.

- Das K, Ghosh S, Natarajan R (2022) Socio‑economic valuation of mangrove ecosystem services in the Indian Sundarbans. Ecological Economics 199: 107-118.

- Chakraborty S, Roy P, Sharma T (2020) Projected Sea‑level rise impacts on the Indian Sundarbans: A GIS‑based vulnerability assessment. Climate Change 162(3): 1557-1572.

- Mandal S, Dutta N, Chakraborty S (2021) Assessing illegal shrimp farming impacts on Sundarbans mangroves using high‑resolution satellite imagery. Marine Policy 134: 104642.

- Mukherjee S, Sarkar P (2023) Poaching dynamics of the Bengal tiger in the Sundarbans: Insights from patrol data analytics. Wildlife Conservation 50(2): 235-250.

- Banerjee S, Kundu S, Chatterjee P (2019) Challenges in mangrove forest monitoring in the Indian Sundarbans. Journal of Environmental Management 239: 149-158.

- Kerr J, Macdonald D, Jones A (2021) AI‑driven early warning system for illegal logging in the Amazon. Conservation Biology 35(5): 1449-1460.

- Hughes TP, Anderson K, Green B (2022) Artificial intelligence for coral reef health monitoring: Lessons from the Great Barrier Reef. Marine Pollution Bulletin 176: 113‑124.

- Feng L, Liu H, Wang Y (2020) Deep learning for Arctic Sea‑ice classification using SAR imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 58(5): 3311-3322.

- Coppin P, Jones J, Woodcock C (2020) Applying machine learning to remote sensing for forest mapping: A review. International Journal of Remote Sensing 41(9): 3215-3241.

- Ahmed S, Rahman M, Hossain M (2021) Deep learning‑based mangrove classification using Sentinel‑2 and SAR data in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Remote Sensing of Environment 260: 112362.

- Ghosh P, Chakraborty A (2022) Transfer learning for mangrove species identification in data‑sparse regions. Environmental Modelling & Software 152: 105‑123.

- Norouzzadeh MS, Nguyen A, Kosmala M (2020) Automatically identifying, counting, and describing wildlife in camera‑trap images with deep learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(25): 14445-14453.

- Bose S, Dutta A, Prasad R (2022) Thermal UAV‑based tiger detection using deep learning in the Sundarbans Tiger Reserve. Ecological Informatics 67: 101494.

- Sharma R, Dutta K (2023) Real‑time passive acoustic monitoring of Ganges river dolphins using edge AI. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 33(2): 567-582.

- Rao P, Singh N, Sen S (2022) Hybrid LSTM‑CNN model for predicting mangrove inundation under climate change scenarios. Environmental Modelling & Software 158: 105‑123.

- Sarkar D, Bandyopadhyay S, Ghosh S (2021) DeepStorm: A deep‑learning framework for early cyclone surge prediction over the Bay of Bengal. Atmospheric Research 260: 105‑119.

- Mitra A, Sengupta D, Roy S (2023) “SundarAI”: A mobile AI platform for community‑based monitoring in the Indian Sundarbans. International Journal of Human‑Computer Interaction 39(7): 657-671.

- Kumar R, Joshi S (2020) Ethical considerations in AI‑enabled wildlife monitoring in India. AI & Society 35(4): 1155-1163.

- Singh V, Das S (2023) Reinforcement‑learning‑based autonomous UAV path planning for wildlife monitoring in mangrove ecosystems. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 167: 104-119.

- Sundarbans Climate Resilience Plan (2022) Government of West Bengal, Department of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

- Zhang Y, Li X, Zhao Q (2020) Generative adversarial networks for super‑resolution of UAV imagery in forest monitoring. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 17(6): 991-995.