Abstract

This study aimed to describe and quantify meristic characters, measure morphometric traits, and conduct molecular characterization of Malapterurus spp. collected from two locations: Kosti (White Nile) and Khashm El Girba (Atbara River). A total of 13 specimens were obtained from each site. Meristic and morphometric data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, regression analysis, and correlation matrices. Molecular analysis was performed using DNA barcoding of the mitochondrial Cytochrome Oxidase I gene to infer phylogenetic relationships between specimens from both locations and to compare them with reference sequences from GenBank. Meristic counts did not show significant differences between the two populations (p≥0.05). However, morphometric analyses revealed statistically significant differences (p≤ 0.05–0.001) in several morphological traits. While meristic traits and PCR amplicon patterns were largely similar, variations in morphology and Cytochrome Oxidase I sequences suggest that the Khashm El Girba population may represent a subspecies of M. electricus or a cryptic species within the genus Malapterurus. Further comprehensive studies across the Nile River system, including its tributaries and reservoir lakes, are recommended to determine whether these populations represent a distinct subspecies of M. electricus, a new species, or previously unrecognized cryptic diversity within Malapterurus.

Keywords:Characterization; Malapterurus electricus; Malapterurus minjiriya; Sudan

Introduction

Fish represent a vital source of nutrition for humans and hold substantial economic value as both a commodity and a source of income. Beyond their dietary importance, fish also provide various products such as pharmaceutical compounds, oils, and leather [1]. Additionally, fish play significant roles in cultural practices, including rituals, festivals, ceremonies, and ethno-medicinal traditions, and are even used in black magic in some African societies [2]. Among the 31 families of catfishes (Order: Siluriformes), only the family Malapteruridae is known to possess an electric organ [3]. These specialized organs generate electric discharges used primarily for defense and territorial behavior, with the intensity of the discharge often varying depending on whether the intruder is a conspecific or not [4].

The species Malapterurus electricus is widely distributed across Africa, particularly within the Sudanian ichthyofaunal province [5]. This species can reach a standard length of up to 122cm and a body weight of approximately 20kg. Morphologically, it is characterized by a grayish-brown dorsum and flanks, with the ventral surfaces being off-white to cream-colored [6]. The electric organ of M. electricus is capable of producing intermittent discharges ranging from 300 to 400volts, with discharge amplitude increasing proportionally with body size [4].

Sagua [7] described Malapterurus minjiriya as a new species from Lake Kainji, Nigeria. This species is generally large and greyish in appearance, while M. electricus exhibits a pale yellowish coloration when freshly caught. Morphologically, M. minjiriya has a wide head, mouth, and snout in contrast to M. microstoma, which possesses a narrower mouth and snout. M. minjiriya has been molecularly characterized by Oladipo et al. [8] from Nigerian inland water bodies and is reported to be widely distributed throughout the Niger River and Volta River systems [7]. It has also been recorded in the White Nile tributaries in Ethiopia and the Omo River [9], and was more recently documented from floodplain rivers in Alitash National Park, Ethiopia [10]. These distribution patterns place both M. electricus and M. minjiriya within the Sudanian ichthyofaunal province.

A comprehensive taxonomic revision of the family Malapteruridae was conducted by Norris [11], who described 14 new species and reorganized the family into two genera: Malapterurus, comprising 16 species divided into “broadmouth” and “small-mouth” groups based on oral morphology, and Paradoxoglanis, comprising three species. Norris noted that taxonomic challenges were encountered during examination of preserved specimens, particularly due to post-mortem shrinkage and deformation caused by the high fleshiness of these fishes.

The use of meristic counts, morphometric measurements, and molecular genetic tools has become essential in modern taxonomic studies, providing more reliable species identification compared to traditional morphological indices [12]. The advancement of DNA barcoding has further facilitated species identification and phylogenetic comparisons through reference databases such as GenBank and the Barcode of Life Database [13]. Recent genomic studies, such as the complete mitochondrial genome sequencing of M. electricus by Li & Jiang [14], have enhanced our understanding of phylogenetic relationships within Siluriformes, using analyses of 13 protein-coding genes across 43 species.

The present study aims to identify Malapterurus species collected from Kosti and Khashm El Girba employing meristic counts and morphometric measurements; and DNA barcoding of the cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene region to construct phylogenetic relationships and compare the sequences with existing data in the GenBank database.

Material and Methods

A total of 26 Malapterurus specimens were collected, comprising 13 individuals from Kosti (White Nile) and 13 from Khashm El Girba (Atbara River). From each specimen, tissue samples approximately 0.5cm³ in size were excised from the dorsal fin and the first gill arch using sterilized, autoclaved instruments to avoid contamination. Each tissue sample was placed in an individual sterile tube and preserved in 100% molecular-grade ethanol for subsequent DNA analysis.

Whole fish specimens were stored on ice immediately after collection to maintain tissue integrity and were transported to the Department of Zoology, University of Khartoum. Upon arrival, specimens were subjected to meristic counts, morphometric measurements, and molecular procedures.

Meristic counts and morphometric measurements

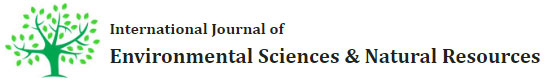

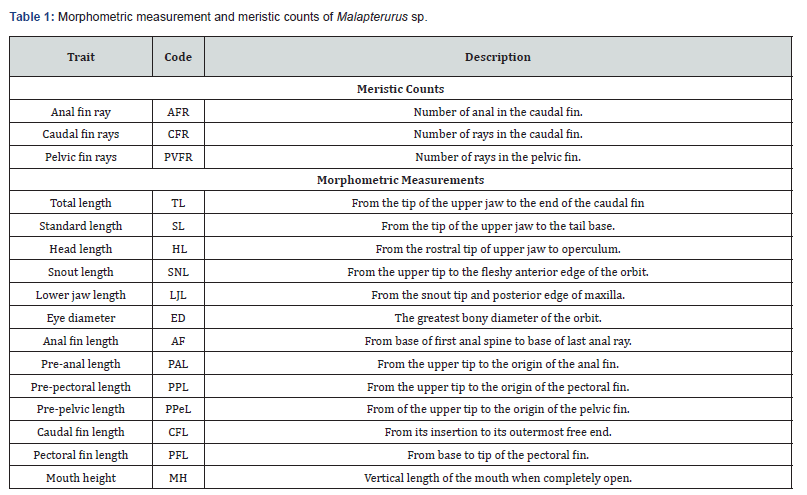

From each identified specimen three meristic counts and 15 morphometric measurements (Figure 1 & 2, Table 1) were recorded from the left side of each fish specimen using a measuring board, a tape and a vernier caliper as appropriate.

DNA extraction using potassium acetate (KAc):

Genomic DNA was extracted from preserved tissue samples following the protocol described by Ghossein et al. [15], with slight modifications. Approximately 100μL of extraction buffer— composed of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 50mM Tris-HCl, 25mM NaCl, and 25mM EDTA, adjusted to pH 8.0—was added to each tissue sample in a 1.5mL microcentrifuge tube. If the pH exceeded 8.0, dilute HCl was added; if lower, NaOH was used to adjust the pH. The tissue was homogenized gently using a sterile glass rod.

Samples were incubated at 68°C for 15 minutes in a water bath. Following this, 100μL of 0.099M potassium acetate (KAc) was added to each tube, which were then placed on ice for 45 minutes and gently inverted periodically to ensure uniform distribution. The samples were centrifuged at 14,000rpm for 10 minutes to pellet cellular debris and protein precipitates. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and this centrifugation step was repeated twice for thorough purification.

DNA was precipitated by adding 600μL of absolute ethanol and incubating the samples at −20°C for at least 2 hours or overnight. After precipitation, tubes were centrifuged at 14,000rpm for 15 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. The DNA pellet was washed with 100μL of 70% ethanol and centrifuged again at 14,000rpm for 10 minutes. This washing step was repeated, followed by a final wash with absolute ethanol. Tubes were inverted on sterile tissue paper and air-dried for approximately 2 hours. DNA purity and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Model: DN1000).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Amplification of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase

subunit I (COI) barcode region was performed using a cocktail of

four oligonucleotide primers:

F2_t1: 5′-TGT AAA ACG GCC AGT CAA ACC ACA AAG ACA TTG

GCA C-3′

FishF2_t1: 5′-TGT AAA ACG GCC AGT CGA CTA ATC ATA AAG

ATA TCG GCA C-3′

FishR2_t1: 5′-CAG GAA ACA GCT ATG ACA CTT CAG GGT GAC

CGA AGA ATC AGA C-3′

FR1d_t1: 5′-CAG GAA ACA GCT ATG ACA CCT CAG GGT GTC

CGA ATA AYC ARA A-3′

PCR reactions were prepared using a commercial PCR premix (Vivantis) in a final volume of 25μL, containing 10pmol of each primer, 2μL of extracted DNA (270-450ng/μL), and 14μL of nuclease-free distilled water.

The PCR thermal cycling protocol was as follows:

Initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, 35 cycles of:

Denaturation at 94°C for 15 seconds, Annealing at 54°C for 25

seconds, Extension at 72°C for 1 minute, Final extension at 72°C

for 5 minutes and Hold at 4°C.

Optimal results were obtained by adjusting the cycling conditions to 30 cycles and lowering the annealing temperature to 49°C. Reactions were performed using a Bioneer thermal cycler.

Amplification success was verified by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel in 1× TBE buffer. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and bands were visualized under UV light. A 100bp DNA ladder (Vivantis) was used as a molecular size marker.

Sequencing and sequence analysis

PCR products were purified and commercially sequenced bidirectionally at BGI (China). Raw sequence data were assembled, visually inspected, and edited using MEGA version 6.06. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the MUSCLE algorithm integrated within MEGA.

Statistical and phylogenetic analysis

Morphometric and meristic data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Version 10.0). Student’s t-tests were conducted to compare the mean values of traits between the two collection sites. Regression analyses were performed to assess correlations among morphometric traits.

Phylogenetic analysis of COI sequences was conducted using MEGA X and GenAlEx 6.5 software. A phylogenetic tree was constructed to visualize genetic relationships among the Malapterurus specimens and to compare them with reference sequences from GenBank.

Results

Morphological characterization

The collected specimens of Malapterurus spp. exhibit a fleshy, elongated, and nearly cylindrical body characteristic of members of the family Malapteruridae. The body surface is soft and devoid of scales or spines, presenting a smooth integument.

The coloration pattern is generally pale brown to gray, irregularly marked with distinct dark or black blotches distributed along the bod back.

The head is relatively broad and slightly depressed anteriorly. Eyes are small, circular, and laterally positioned, reflecting adaptation to turbid or low-light habitats. The lips are thick and fleshy, surrounding a wide terminal mouth. Two short maxillary barbels are present on the upper jaw, while four longer mandibular barbels arise from the lower jaw margins.

The pectoral and anal fins are rounded, each supported by 6–8 soft fin rays, and are inserted approximately midway between the snout tip and the caudal base. The anal fin is long and bears 10–12 soft rays. The adipose fin is located posteriorly and dorsally just before the caudal fin.

The caudal fin is rounded and with 16-19 rays, giving the posterior end a blunt appearance.

The lateral line originates above the base of the pectoral fin and extends continuously to the middle of the caudal peduncle.

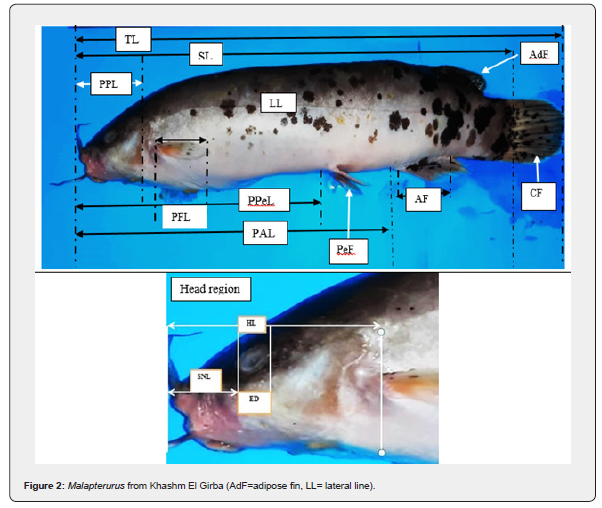

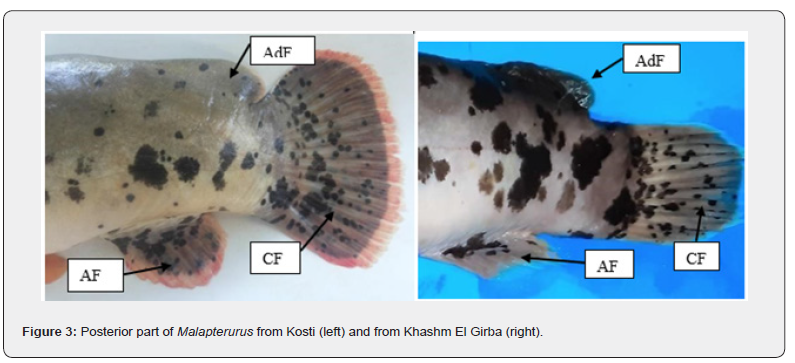

However, variations in pigmentation intensity and fin ray counts noted between the two populations, were illustrated in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 2.

Overall, the diagnostic traits confirm that all examined individuals belong to the genus Malapterurus, sharing typical morphological adaptations of electric catfishes.

The comparative morphological assessment of Malapterurus specimens from Kosti and Khashm El Girba (Figure 3, Table 2) reveals several consistent external distinctions suggestive of ecological or population-level differentiation. The lateral line in Kosti individuals is irregular and slightly undulating, whereas in Khashm El Girba specimens it remains nearly straight, indicating possible variation in the mechanosensory system associated with local hydrodynamic or substrate conditions. Head morphology also differs, being pointed in Kosti fish and rounded in those from Khashm El Girba.

The adipose fin is continuous with the body in Kosti individuals but distinctly separated in specimens from Khashm El Girba. This difference may hold taxonomic relevance or reflect adaptation to differing swimming efficiencies. The caudal fin of Kosti fish is truncate and fan-shaped, suited for brief periods of rapid movement, while that of Khashm El Girba specimens is rounded, enhancing maneuverability in different water currents. Coloration of the caudal fin further distinguishes the two populations: Kosti individuals display a predominantly black fin with a pale margin, whereas those from Khashm El Girba exhibit a uniform pale grey coloration, potentially linked to visual signaling.

Body shape varies markedly between populations. Kosti fish possess a non-cylindrical form with a distinct dorsal hump, while Khashm El Girba specimens are more cylindrical and streamlined, possibly reflecting adaptation to faster or deeper waters. Pigmentation patterns also differ: Kosti specimens exhibit broader interspaces between irregular blotches, with dense melanophore concentration toward the posterior region, whereas Khashm El Girba individuals show narrower interspaces and more continuous pigmentation along the mid-ventral line. The anal fin in Kosti fish is rounded, contrasting with the longer, tapering form in Khashm El Girba individuals.

These differences probably resulted from environmental factors and need more study to interpret their taxonomic importance.

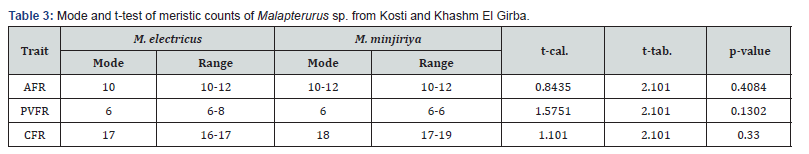

Descriptive statistics

The results in Table 3 show meristic count comparisons between Malapterurus electricus and M. minjiriya from Kosti and Khashm El Girba. The mode was used as a descriptive measure, and t-tests were applied to compare the traits. For AFR, PVFR, CFR, the calculated t-values (0.8435, 1.5751, and 1.1010) are lower than the tabulated t-value (2.101) at the significance level α=0.05. Corresponding p-values (0.4084, 0.1302, 0.3300) all exceed 0.05, indicating that there are no statistically significant differences between the two populations for these meristic traits (Table 3).

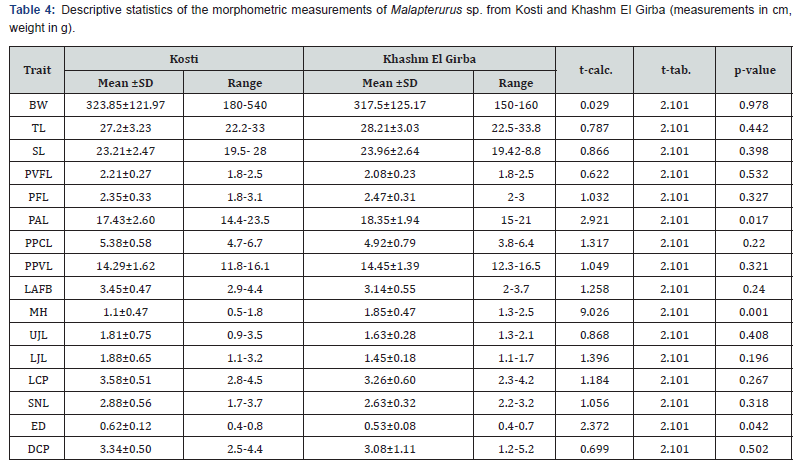

A comparative analysis of morphometric traits between Malapterurus specimens collected from Kosti and Khashm El Girba (Table 4) revealed that the majority of traits did not differ significantly between the two populations (p>0.05). This indicates a high degree of morphological similarity, suggesting that these populations may belong to the same species or exhibit only minor geographical variation.

Specifically, traits such as body weight (BW), total length (TL),

standard length (SL), pelvic fin length (PVFL), pectoral fin length

(PFL), prepectoral length (PPCL), prepelvic length (PPVL), length

of adipose fin base (LAFB), upper jaw length (UJL), lower jaw

length (LJL), length of caudal peduncle (LCP), snout length (SNL),

and depth of caudal peduncle (DCP) all showed no statistically

significant differences (p>0.05). The calculated t-values for these

traits remained below the critical value (t-tab. =2.101), reinforcing

the absence of significant morphological divergence. However,

three traits exhibited statistically significant differences between

the populations:

a) Preanal Length (PAL): Individuals from Khashm El Girba

had significantly longer preanal lengths (p=0.017), suggesting a

potential variation in body proportion.

b) Maximum Head Height (MH): A highly significant

difference was observed in head height (p = 0.001), with

Khashm El Girba specimens showing greater values. This trait

may reflect ecological or functional adaptations specific to local

environmental conditions.

c) Eye Diameter (ED): Also differed significantly (p=0.042),

with larger values in the Kosti population. This may relate to

sensory adaptations.

These significant differences in MH, PAL, and ED could represent localized adaptations, intraspecific variation, or the presence of cryptic diversity. Nonetheless, as the majority of morphometric traits remain statistically indistinguishable, the overall morphological divergence between the two populations appears limited.

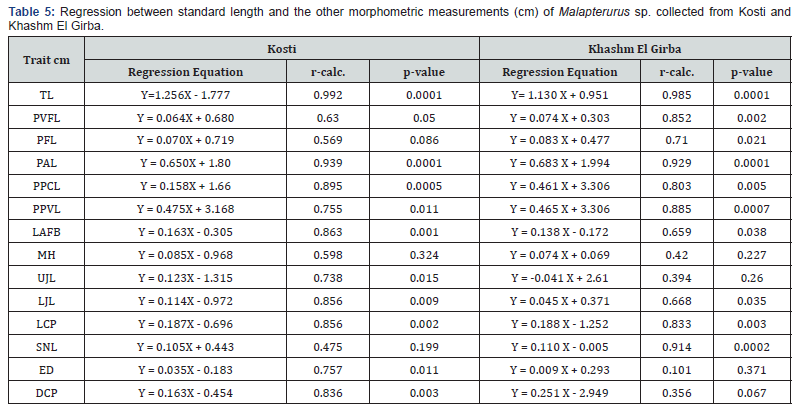

Linear regression analyses (Table 5) were conducted to examine the relationships between various morphometric traits (dependent variables) and standard length (independent variable) in Malapterurus spp. populations from Kosti and Khashm El Girba. The results show a high degree of linearity in several traits, although the strength and significance of these relationships varied between traits and populations.

Strong correlations (r>0.85, p<0.01)

Both populations exhibited strong and statistically significant

correlations between standard length and several key traits:

a) Total Length (TL): Exhibited extremely strong positive

correlations in both Kosti (r=0.992) and Khashm El Girba (r=0.985),

with highly significant p-values (p=0.0001). This indicates a

consistent and predictable relationship between standard and

total body length, which is expected in morphometric scaling.

b) Preanal Length (PAL), Prepectoral Length (PPCL), Lower

Caudal Peduncle Length (LCP), and Eye Diameter (ED) (in Kosti)

also showed strong and significant correlations, confirming these

traits scale proportionally with body size in both populations.

c) Snout Length (SNL): Showed a very strong correlation

in the Khashm El Girba population (r = 0.914, p=0.0002), but

was weaker and non-significant in Kosti (r =0.475, p=0.199),

indicating potential regional variation in how snout length scales

with body size.

Moderate correlations (r=0.6–0.85)

Traits such as: Prepelvic Length (PPVL), Length of Adipose Fin Base (LAFB) and Lower Jaw Length (LJL), demonstrated moderate (r=0.6–0.85) but significant (p-0.0007, p-0.038 and p=0.035. respectively) correlations in both populations. The regression coefficients suggest these traits increase with standard length, albeit with more variability than the primary body dimensions.

Maximum Head Height (MH) and Upper Jaw Length (UJL) in both populations showed low correlation coefficients (r<0.75), with non-significant p-values, particularly in Khashm El Girba, where the relationships were negligible (p>0.2).

Weak or non-significant correlations

Several traits exhibited weak or non-significant relationships with standard length: The eye Diameter (ED) in Khashm El Girba showed a very weak and non-significant correlation (r=0.101, p=0.371), contrasting with a moderate and significant correlation in the Kosti population (r=0.757, p=0.011). This could suggest environmental or genetic factors influencing eye development in the two locations. Depth of Caudal Peduncle (DCP) in Khashm El Girba also showed a non-significant correlation (p =0.067), whereas in Kosti the relationship was statistically significant (r=0.836, p= 0.003).

Molecular identification of the electric catfish specimens

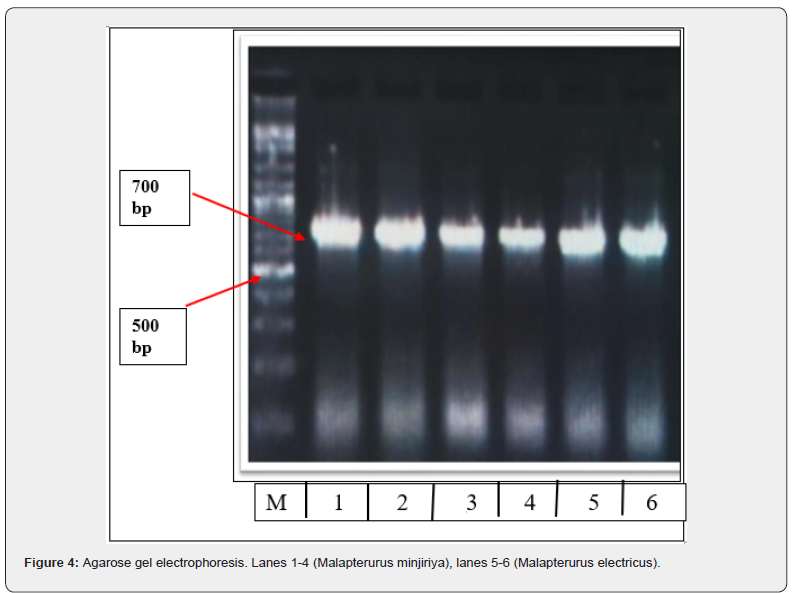

Two specimens from Kosti and four from Khashm El Girba were selected for analysis based on the quality and purity of their extracted DNA. PCR amplification of the mitochondrial CO1 gene produced amplicons of approximately 700 base pairs. The fragment sizes were confirmed using gel electrophoresis with a 100bp DNA ladder as a molecular size marker (Figure 4).

Sequence analysis

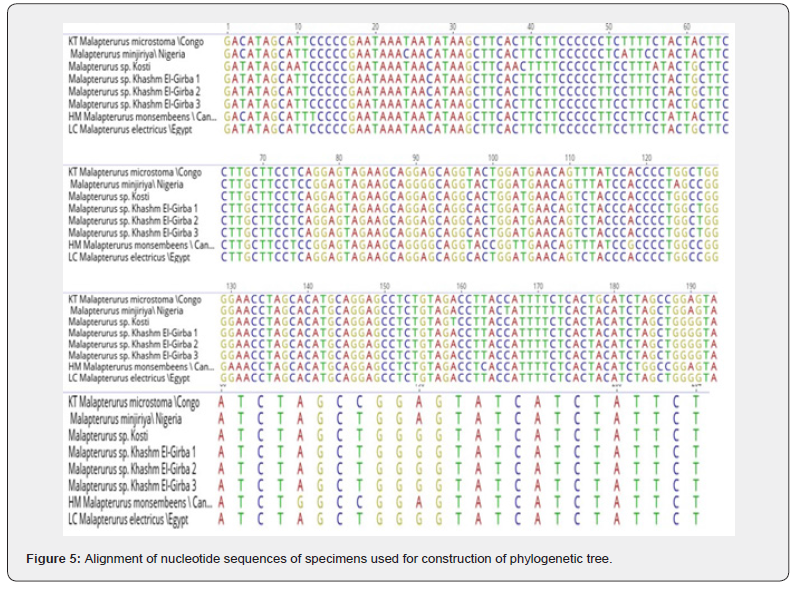

A total of ten CO1 gene sequences were obtained, five from each location. However, six sequences were excluded due to low quality and poor read reliability. The remaining four highquality sequences were subjected to BLAST analysis against the NCBI GenBank database, revealing a 97% identity match with Malapterurus electricus. These sequences were subsequently used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the Geneious Prime software (Figure 5). The figure revealed a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of mitochondrial or nuclear DNA sequences from different species or populations within Malapterurus spp. The sequences showed:

a) The alignment includes individuals from various

geographic locations: Sudan (e.g., Kosti and Khashm El-Girba),

Congo, Nigeria, and Egypt.

b) The taxa represented include Malapterurus microstoma,

M. minjiriya, M. monsembeensis, and undescribed Malapterurus

spp., indicating a possible phylogenetic or biogeographic trait.

c) Most of the bases from position ~30 to ~70 are

conserved across taxa (many repeated ‘C’ and ‘T’ residues),

indicating a functionally important or evolutionarily constrained

region. Positions like 2, 3, 6, 7, 14, and 22 show single nucleotide

polymorphisms (SNPs), suggesting these could be phylogenetically

informative or diagnostic sites. These variations can help infer

relationships among taxa and identify possible cryptic species.

d) High similarity among the Khashm El-Girba samples (1–

3) implies they may represent a single lineage or closely related

population.

e) The Congo and Egypt samples showed similarities but

are distinguishable from each other and the Sudanese specimens,

suggesting possible speciation or geographic structuring.

f) Many positions (e.g., 144–148, 160–168) are identical

across all sequences, indicating evolutionary conservation. These

are likely corresponded to functionally important regions (e.g.,

protein-coding genes or structurally conserved RNA regions).

g) Positions such as 133, 137, 151, 174, 181, 188, and 198

showed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). For example,

position 137: (M. microstoma (Congo): T; M. minjiriya (Nigeria):

C and Malapterurus sp. Kosti and Khashm El-Girba: C) suggestsed

possible divergence between M. microstoma and other lineages.

h) Malapterurus monsembeensis from Congo and M.

electircus from Egypt are similar to each other but distinct from

the Sudanese samples.

i) Malapterurus microstoma (Congo) shows notable

differences, especially in variable sites, indicating potential

genetic isolation and deeper divergence.

j) The presence of multiple fixed nucleotide differences

among taxa supports the hypothesis of reproductive isolation and

speciation. For example, Position 188: Congo sample (G), while

others showed C, G, or T, suggesting lineage-specific mutations.

k) Differences between Malapterurus species/populations

from West Africa (Nigeria), Central Africa (Congo), Northeast

Africa (Sudan, Egypt), and unknown (monsembeensis) reflect the

phylogeographic structure of the genus. These patterns likely

reflect historical river system separations, vicariance events, or

long-term isolation in distinct freshwater systems.

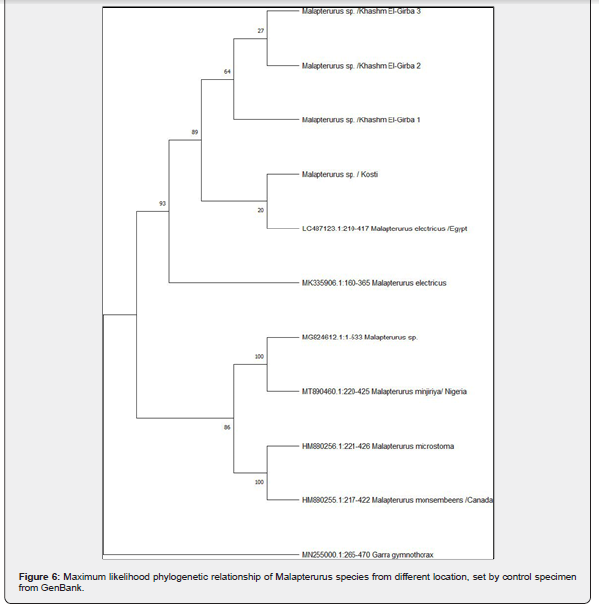

The maximum likelihood or neighbor-joining tree, Figure 6, showed the evolutionary relationships among different species or populations within Malapterurus spp. based on genetic sequence data.

The tree is rooted with Garra gymnothorax (MN255000.1:265- 470) as an outgroup, which provides a reference point for the evolutionary divergence of the ingroup (Malapterurus sp.).

Bootstrap values are shown on the nodes, representing the statistical support for each clade. Values close to 100 indicate high confidence in that branch’s validity.

The Malapterurus sequences formed two main clades (Figure

6):

Clade A (upper part) including individuals from Khashm El-

Girba (1, 2, 3) and Kosti (all Sudan).

These group are close to sequences identified as M. electricus from Egypt (LC487123.1) and another M. electricus sequence (MK335906.1), suggesting these samples may represent the same species. The low bootstrap support at certain nodes (e.g., 20, 27) may indicate genetic similarity.

Clade B (lower part) including sequences from Nigeria (MT890460.1: M. minjiriya and M. microstoma: HM880256.1); M. monsembeens from Canada (HM880255.1) which is likely a database location rather than native origin and a MG824612.1: Malapterurus sp.This clade shows strong bootstrap support (86– 100), indicating well-supported differentiation among these taxa.

The tree shows clear genetic divergence within Malapterurus, supporting the existence of multiple distinct species. The Sudanese populations (Khashm El-Girba and Kosti) appear closely related to M. electricus, but possibly form a distinct subclade, suggesting they may represent regional variants or subspecies.

Malapterurus minjiriya, M. microstoma, and M. monsembeens form a highly supported and genetically distinct clade, indicating strong species boundaries.

Discussion

In general, Kosti specimens showed more consistently strong and significant linear relationships across a broader range of traits. Khashm El Girba specimens, while also showing several strong correlations, exhibited more variability and weaker associations in traits related to cranial morphology (e.g., MH, UJL, ED). Maximum Head Height (MH) and Upper Jaw Length (UJL) in both populations showed low correlation coefficients (r<0.75), with non-significant p-values, particularly in Khashm El Girba, where the relationships were negligible (p>0.2). This indicates that these head-related traits may not scale consistently with body size, possibly reflecting ecological or behavioral adaptations rather than simple allometric growth.

The observed differences in regression slopes and intercepts for traits such as total length (TL) and preanal length (PAL) may indicate delicate regional variations in growth trajectories between the Kosti and Khashm El Girba populations. These variations could be attributed to environmental influences— such as differences in habitat structure, food availability, or water parameters—as well as potential genetic divergence between the populations. Such factors can affect allometric growth patterns, leading to population-specific morphological scaling relationships. Overall, the Malapterurus specimens from Kosti exhibited more consistent and statistically significant linear relationships across a wider range of morphometric traits when compared to those from Khashm El Girba. In contrast, although the Khashm El Girba population demonstrated some strong correlations, greater variability was observed, particularly in traits associated with cranial morphology—such as Maximum Head Height (MH), Upper Jaw Length (UJL), and Eye Diameter (ED). Specifically, both MH and UJL exhibited low correlation coefficients (r < 0.75) in both populations, with non-significant p-values, especially in the Khashm El Girba group (p > 0.2). These weak correlations suggest that cranial traits may not scale predictably with overall body size, potentially reflecting ecological or behavioral differentiation rather than simple allometric growth.

Variability in cranial proportions is often linked to ecological specializations, such as differences in prey type, feeding strategies, or habitat use [16,17]. In electric catfish, where feeding and electroreception are closely tied to cranial morphology, such variations may indicate localized adaptations or developmental plasticity in response to environmental conditions [18]. The reduced consistency of head-related traits in the Khashm El Girba specimens may thus reflect population-level divergence shaped by ecological pressures or differing selective regimes.

Furthermore, the observed differences in regression slopes and intercepts for key body traits such as Total Length (TL) and Pre-Anal Length (PAL) between the two populations suggest distinct growth trajectories. These differences may be indicative of regional variation in developmental patterns, possibly driven by environmental heterogeneity. Factors such as habitat complexity, prey availability, hydrological dynamics, and water chemistry have been widely recognized as drivers of phenotypic plasticity and morphological differentiation in freshwater fishes [19-21].

The divergence in allometric scaling patterns may reflect underlying genetic differentiation between the two populations. Geographic isolation and limited gene flow can lead to microevolutionary changes, which in turn affect the ontogenetic routes of morphological traits. In this context, the morphological discrepancies between the Kosti and Khashm El Girba populations may not only be environmentally induced but may also signify incipient speciation or cryptic diversity, particularly in light of the weak molecular divergence observed in COI-based analyses.

The interaction between genetic and environmental influences on morphometric variation has been widely acknowledged in ichthyological research, particularly in studies addressing population structure and species delimitation [22]. Therefore, the current findings stress the importance of integrating both morphometric and molecular approaches to better understand the evolutionary and ecological processes shaping diversity within the Malapterurus genus.

Molecular analyses of Malapterurus spp., through mitochondrial markers such as COI, enable the alignment of conserved and variable genetic regions, providing a foundation for phylogenetic inference. Methods such as Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference utilize these alignments to reconstruct evolutionary relationships, estimate genetic distances, and infer divergence times among taxa [23]. These phylogenetic frameworks are essential for resolving species boundaries, especially in groups with cryptic diversity or overlapping morphological traits, as has been suggested in Malapterurus [8,18].

Species delimitation based on molecular evidence has led to several taxonomic revisions within the genus, highlighting the need for integrative approaches combining morphology and genetics [22]. Such efforts are critical for accurately characterizing biodiversity and ensuring proper classification, especially in understudied freshwater taxa.

Furthermore, identifying distinct evolutionary lineages within Malapterurus has direct implications for conservation biology. Recognizing cryptic or geographically restricted species can inform conservation priorities and strategies, particularly in light of habitat degradation and hydrological alterations affecting African river system.

Molecular phylogenetics also supports biogeographic studies by elucidating historical dispersal and isolation patterns. For instance, phylogeographic analyses can help trace lineage diversification and migration routes across major African basins such as the Nile, Niger, and Congo systems, offering insights into the continent’s freshwater evolutionary history [24,25].

Norris [11] classified the family Malapteruridae into two genera: Malapterurus and Paradoxoglanis, and further subdivided Malapterurus into 16 species, based on mouth morphology into broad- and small-mouthed species.

Iyiola et al. [26] reported an enigmatic Malapterurus species (GenBank accession: MG824612) from north-central Nigeria. Subsequently, Oladipo et al. [8] identified this specimen as M. minjiriya using cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) barcoding. While the morphological characteristics of the Malapterurus specimens from Khashm El Girba closely resemble those described by Iyiola et al. [26] and Oladipo et al. [8], molecular analyses in the present study, based on COI sequencing, contradict Oladipo et al. [8], taxonomic placement. Instead, our genetic data suggest that the Khashm El Girba specimens are more closely related to M. electricus, potentially representing a subspecies or a cryptic lineage within M. electricus.

One plausible explanation for the existence of cryptic species is proposed by Bickford et al. [22], who argued that organisms relying on non-visual modalities for communication and reproduction (e.g., sound, vibration, pheromones, or electric signals) are more likely to harbor cryptic diversity. This hypothesis is supported by studies on African weakly electric fish of the family Mormyridae [27], where cryptic speciation has been well documented.

Jirsová et al. [28], employing mitochondrial markers (COI, Cytb), investigated cryptic diversity in African squeaker catfish and found that multiple morphotypes and intermediates were conspecific, despite inconclusive nuclear data. They introduced the notion of “species-like” entities to describe taxa lacking consistent morphological differentiation. Similarly, the present study provides molecular evidence supporting the conspecificity of Malapterurus specimens exhibiting morphological variation, suggesting the potential presence of cryptic subspecies, consistent with the findings of Jirsová et al. [28].

Conclusion

Structuring and species-level divergence within Malapterurus. Sudanese Malapterurus may require taxonomic re-evaluation, as they may not be genetically identical to known M. electricus from Egypt. Additional sampling and morphological comparisons are needed to clarify species boundaries, especially for unnamed “Malapterurus sp.” entries. This phylogenetic analysis is consistent with species diversification driven by geography and possibly ecological specialization.

The tree supports molecular identification as a reliable method for distinguishing among Malapterurus species.

Ethics

Ethics approval and consent to participate, human and animal rights, consent for publication, availability of data and materials are not applicable.

References

- Nelson JS (2006) Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0- 471-25031-7.

- Orilogbon JO, Adewole AM (2011) Ethnoichthyological knowledge and perception in traditional medicine in Ondo and Lagos States, southwest Nigeria. Egyptian Journal of Biology 13: 1-8.

- Howes GJ (1985) The phylogenetic relationships of the electric catfish family Malapteruridae (Siluroidei). J Nat Hist 19(1): 37-67.

- Rankin CH, Moller P (1986) Social behavior of African electric catfish, Malapterurus electricus, during intra and interspecific encounters. Ethology 73(3): 177-190.

- Neumann D, Obermaier H, Moritz T (2016) Annotated Checklist for fishes of the Main Nile Basin in the Sudan and Egypt based on recent specimens records (2006-2015). Cybium 40(4): 287-317.

- Abu Gideiri YB (1984) Fishes of the Sudan, Khartoum University Press, p. 166.

- Sagua VO (1987) On a new species of electric catfish from Kainji, Nigeria, with some observations on its biology. J Fish Biol 30(1): 75-89.

- Oladipo SO, Nneji LM, Anifowoshe AT, Nneji IC (2020) Molecular characterization of Malapterurus minjiriya Sagua, 1987 and phylogenetic relationships within the genus Malapterurus (Silurifomes, Malapteruridae) from Nigerian inland water bodies. Journal of Fish Biol 97(6): 1865-1869.

- Golubtsov AS, Berendzen PB (1999) Morphological evidence for the occurrence of two electric catfish Malapterurus spp. species in the White Nile and Omo- Turkana systems (East Africa). Journal of Fish Biology 55(3): 492-505.

- Eyayu A (2019) Fish Biology and Fisheries of the Floodplain Rivers in the Alitash National Park, Northwestern Ethiopia. A thesis submitted to the Department of Zoological Sciences, Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology (Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences), p. 285.

- Norris SM (2002) A revision of the African electric catfishes, family Malapteruridae (Teleostei, Siluriformes), with erection of a new genus and descriptions of fourteen new species, and an annotated bibliography. l". Annalen van het museum voor Midden-Afrika (serie Zoölogie). Tervuren, Belgium.: Royal Museum for Central Africa 289: 1-155. ISSN 1781-

- Omer OM, Abdalla HA, Mahmoud ZN (2020) Genetic Diversity of Two Tilapia Species (Oreochromis niloticus and Sarthrodon galilaeus) Using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA. The Open Biology Journal 7: 3-9.

- Hubert N, Hanner R, Holm E, Mandrak NE, Taylor E, et al. (2008) Identifying Canadian Freshwater Fishes through DNA Barcodes. PLoS ONE 3(6): e2490

- Li Y, Jiang H (2022) The complete mitochondrial genome of electric catfish Malapterurus electricus and its phylogeny. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour 7(3): 525-527.

- Ghossein RA, Ross DG, Salmon N, Rabson AR (1994) A Search for Mycobacterial DNA in Sarcoidosis Using the Polymerase Chain Reaction. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 101(6): 733-737.

- Wainwright PC, Alfaro ME, Bolnick DI, Hulsey CD (2004) Many-to-one mapping of form to function: A general principle in organismal design? Integrative and Comparative Biology 45(2): 256-262.

- Clabaut C, Bunje PME, Salzburger W, Meye A (2007) Morphological divergence and convergence in African cichlids: The role of evolutionary constraints and ecological factors. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 91(1): 103-113.

- Sullivan JP. LavouéS, Hopkins CD (2000) A phylogenetic analysis of the electric catfish family Malapteruridae (Teleostei: Siluriformes) based on mitochondrial DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 16(3): 403-417.

- Rohlf FJ, Marcus LF (1993) A revolution in morphometrics. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 8(4): 129-132.

- Schaefer SA, Lauder GV (1996) Testing historical hypotheses of morphological change: Biomechanical decoupling in loricarioid catfishes. Evolution 50(4): 1661-1675.

- McGuigan K, Franklin CE, Moritz C, Blow MW (2003) Phenotypic variation and response to selection in wild populations of rainbow fish. Evolution 57(1): 104-118.

- Bickford D, Lohman DJ, Sodhi NS, Peter KL, Meier R, et al. (2007) Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 22(3): 148-155.

23. Felsenstein J (2004) Inferring Phylogenies. Journal of Classification 22(1): 139-142

24. Pinton A, Agnèse JF, Paugy D, Otero OA (2013) large-scale phylogeny of Synodontis (Mochokidae, Siluriformes) reveals the influence of geological events on continental diversity during the Cenozoic. Mol Phylogenet Evol 66(3): 1027-1040.

- Markert JA, Schelly RC, Stiassny ML (2010) Genetic isolation and morphological divergence mediated by high-energy rapids in two cichlid genera from the lower Congo rapids. BMC Evol Biol 10: 149.

- Iyiola OA, Nneji LM, Mustapha MK, Nzeh GC, Oladipo SO, et al. (2018) DNA barcoding of economically important freshwater fish species from north–Central Nigeria uncovers cryptic diversity. Ecology and Evolution 8(14): 6932-6951.

- Feulner PD, Kirschbaum F, Schugardt C, Ketmaier V, Tiedemann R (2006) Electrophysiological and molecular genetic evidence for sympatrically occurring cryptic species in African weakly electric fishes (Teleostei: Mormyridae: Campylomormyrus). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39(1): 198-208.

- Jirsová D, Štefka J, Blažek R, Malala JO, Lotuliakou DE, et al. (2019). From taxonomic deflation to newly detected cryptic species: Hidden diversity in a widespread African squeaker catfish. Nature Scientific Reports 9: 15748.