Abstract

Successful implementation of the ocean economy depends on the capacity of the state agents, effective systems of collaborations, leadership, and consensus on policy framework. Ocean economy poses a challenge regarding striking a balance between social and economic development as well as environmental conservation. Through document analysis, this paper examined the challenges faced by Ocean Phakisa model of South Africa. The ocean economy of South Africa, known as ocean Phakisa, is based on the Big Fast Results concept used in Malaysia, hence this study analysed its conceptualization and institutionalization. The focus of this study was more on the fundamental challenges that hinders the implement ability of the Ocean Phakisa model. This study may add value to the policy discourse around South Africa’s Ocean economy. The findings of this study show that although ocean Phakisa is modelled on the Malaysian Big Fast Results, however, there are shortcomings regarding governance, inclusivity, leadership, policy certainty and conflict of interests. To ensure effective implementation of Ocean economy in South Africa, it is vital to reconsider the enabling elements of Operation Phakisa model. Among these elements are; overarching policy that underpin ocean economy, governance and institutional arrangement as well as effective mechanisms of managing contradictions. Some of the recommendations involves the reconfiguration of the driving champion of Ocean Phakisa based on mandates, the institutional mechanism which is inclusive and spatial planning which takes into consideration the sea land interface.

Keywords: Operation phakisa; Ocean’s economy; Big fast results; Blue economy

Introduction

About two-thirds of our planet is covered by the ocean which provides critical ecosystem services that are essential to people’s well-being, food security, economic development and job security. The oceans economy provides considerable growth prospects while also posing problems due to the multifaceted complexities of its implementation and intrinsic conflicting interests. The South Africa’s Ocean economy model is called Operation Phakisa (Phakisa meaning ‘to hurry’ in Sesotho). However, the intensive pressure, especially posed by the economic development activities to the ocean ecosystems is vast. Balancing environmental conservation with economic development is always a challenge because most governments and businesses prioritize economic growth, often at the expense of the environment. The OECD [1] describes the ocean as the next great economic frontier as it holds potential for wealth and economic growth, employment and innovation. The concept of oceans economy was endorsed in 2012 Rio DE Jeneiro held by the United Nations Conference on sustainable development [2]. Globally, the concept of ocean economy is underpinned by commitments such as the 17 United Nations (UN) Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which include goals and targets that aim at accelerating nation’s development while balancing social, economic, and environmental sustainability. Globally, the ocean economy which consists of marine tourism, aquaculture, shipping, and other ocean activities approximately generate $2.5 trillion per year [2].

According to the OECD [2] during the mid-1990s, ocean economic activity has surged, leading to both an unprecedented use of ocean resources and exponential development of new products to use the ocean. This continuing growth of the ocean economy, often outpacing the growth of the global economy, boosts economies and jobs but also increases environmental impacts, contributing to further damage of the ocean’s health.

South Africa is endowed with coastal resources and account for more than 2,850km of the coastal stretch. About 5.4% (57 736km2) of the South African ocean is protected by 42 Marine protected areas. Over 33% of South African population lives in coastal areas including fishing communities. However, fishing communities are considerably the poorest of the poor and face many challenges that render them vulnerable [3].

In South Africa, coastal goods and services alone are estimated to contribute over a third (35%) to our gross domestic product (GDP). The concept of the ocean economy is defined as that ‘portion of the economy that relies on the ocean as an input to the production process or which by geographic location, takes place on or under the ocean’ [4]. Ocean’s economy includes activities such as offshore oil gas exploration, shipping, shipbuilding and marine equipment, fisheries and fish processing, aquaculture as well as coastal and marine tourism [5]. While there is no accepted definition of the concept of an ‘oceans economy’, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines the ocean economy as the sum of the economic activities of ocean-based industries, together with the assets, goods, and services provided by marine ecosystems [2].

Methods

To gain insights and understanding about the challenges of Ocean Phakisa, this study used document analysis. Document analysis is a systematic approach for reviewing or evaluating documents, both printed and electronic material [6]. This paper examined two areas of Ocean Phakisa, that is, conceptualization and execution. Since Ocean Phakisa is a benchmark exercise, this study examined the benchmarker’s perspective in terms of conception and execution. Data was gathered through government documents, academic papers, and print media. Thematic analysis was used to frame the discussions and the themes that emerged from document analysis are discussed in the next section.

Historical Background of Blue/Ocean Economy

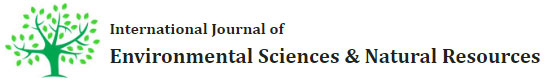

In 2012 The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development was held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil under the two-pronged theme that is: a) a green economy in the context of sustainable development poverty eradication; and b) the institutional framework for sustainable development. The Green Economy was also introduced and promoted as a solution to the global financial crisis and the global climate crisis [7]. South Africa attended the conference represented by former President Jacob Zuma. Since green economy is mainly concerned with terrestrial environment, many coastal countries were concerned about its relevance to them [8]. This concern from coastal countries gave birth to the concept of blue economy which was viewed as the sustainable economic model that considered conservation-based utilization and management of oceans and their coasts. To this end the report titled Green Economy in a Blue World was released in 2012 [9]. From this background, it can be deduced that Blue Economy share a part of its origin in the concept of the Green Economy [10] and both are strongly underpinned by a principle of sustainable development. Although the two concepts are interrelated, however, they can be differentiated from each other. The Green Economy is more incline towards sectors of transport, energy, and on occasion forestry and agriculture whereas the Blue Economy focuses on sectors such as fisheries, marine resources and coastal resources [10]. From this historical background it is apparent that the South African Ocean Phakisa model is a hybrid of both the Green Economy and Blue Economy as it is shown in the Table 1. This hybrid model raises a question about the blueness of the Ocean Economy as the blue aspect of the ocean economy advances the sustainability agenda.

According to Table 1, there are inherent conflicts in South Africa’s Operation Phakisa model due to different sectoral mandates. For example, both the marine protected areas and offshore oil and gas exploration are seeking expansion within the exclusive economic zone. Currently only 5.4% of the marine environment within the South African mainland EEZ is protected [11] and the rest is subject to a right or lease for offshore oil and gas exploration or production. The South African government has signalled its enthusiasm to exploit these resources by openly promoting the drilling of 30 hydrocarbon exploration wells off South Africa’s coast within a decade [12]. Challenges of Blue or Ocean Economy are also exacerbated by the misconception that this type of economy is a distinct economic sector, as opposed to a broader philosophy for economic growth. Making matters worse is the fact that South Africa does not have a national green economy strategy [13] which should clarify distinctions and synergies with Blue Economy.

Results and Discussion

Discussions about the complexities of implementing Ocean Phakisa in South Africa are framed around six focus areas, that is, i) conceptualization of Ocean Phakisa, ii) discussion about terminologies, iii) conflict of interest, iv) valuing the ocean, v) marine spatial planning fragmentation and vi) the land-based problems. Struwig et al. [5], also studied challenges of oceans economy in South Africa, however, they focused on the following areas; pollution, mainly oil spills and dumping at sea, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, climate change and disease events. Zulu et al. [14], focused on the challenges faced by SMMEs operating in the ocean economy in KwaZulu-Natal province. The six focus areas which were identified through document analysis are discussed below.

Conceptualization of ocean phakisa

Ocean’s economy agenda of South Africa is part of Operation Phakisa. Operation Phakisa is a benchmark exercise which was modelled from the Malaysia’s government transformation programme (GTP) which followed the Big Fast Results (BFR) methodology. The Malaysia GTP was designed to implement vision 2020 which was developed in 1991 by prime minister Mahathir bin Mohamad [15]. In 2010, government of Malaysia announced an economic transformation programme to grow the economy of the country. Since the government of Malaysia had only ten years to implement this special programme they adopted a BFR methodology. The GTP was based on the government reform agenda called People first, Performance Now which was introduced by prime minister Najib. To successfully implement this programme, the government of Malaysia employ different strategies which are discussed below:

a) Special purpose vehicle: The prime minister of Malaysia established a special ministry called Performance Management and Delivery Unit (PEMADU) to drive the government transformation programme. PEMADU was housed in the prime minister’s office and tasked with the responsibility of monitoring and improving the performance of government ministries through effective implementation and coordination of the GTP [16].

b) Political Champion: A specific minister was appointed by the prime minister to lead the implementation of the GTP [17]. This new minister had special skills from the corporate world such as turnaround strategic and investment capabilities.

c) Technical support structures: Delivery task forces (DTFs) was formed, one in focus area. Chaired by the Deputy Prime Minister (initially the PM) and attended by the minister of the lead ministry, other relevant ministers, CEO of PEMANDU and senior civil servants.

d) Accountability, monitoring and evaluation: The DTF meets every month to assess the progress on NKRAs and resolve any impediments to achieving performance targets [18].

e) Financial support: As the flagship programme, the GTP received substantive funding from government in order to implement the special interventions.

Although South Africa’s operation Phakisa is modelled on the Malaysians GTP, however, the differences are quiet glaring. For example, South Africa’s Ocean Phakisa is not implemented through a special purpose vehicle. Despite the high strategic and cross cutting nature of Ocean Economy, government failed to house the programme in the presidential office. From inception, Oceans Phakisa despite being copied from GTP of Malaysia, show poor institutionalisation. Discrepancy in institutionalisation of Ocean Phakisa can undermine the implementation of the projects. Notable, lack of cohesion in ocean governance is one of the fundamental challenges of Ocean Phakisa as identified by the Parliamentary monitoring group [19]. Contrary to the latter, one of the success factors of the Malaysian GTP was the well-coordinated governance of the programmes through clearly defined accountability structures.

Discussion of terminologies: oceans vs blue economy

The government of South Africa chose the concept of oceans economy as a policy position for the country. This concept is contained in the oceans economy master plan which is part of operation Phakisa. The field of ocean economics is still evolving after several decades of effort, and the use of oceans economy concept remains uneven and confusing [20]. The Ocean Economy describes economic activity that indirectly or directly uses the ocean as an input or from the production side [21]; it can also describe economic activity from the consumption side, often applied to the commercial and recreational fishing industry (NOAA, 2016). According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD Citation2016), the ocean economy is defined as the economic benefit and value realised from the earth’s oceans and coastlines. The ocean economy is one that includes all economic activities closely linked to the ocean resources and environment and / or dependent to some meaningful degree on the ocean’ (Hosking 2017). This definition has been accepted as the most appropriate for South Africa.

The question is whether or not this definition includes freshwater aquatic resources, or it is only confined to the seawater. This is necessary because, one of the economic sectors of Ocean Phakisa is aquaculture. Most countries around the world opted for the concept of blue economy. The Blue Economy describes the sustainable use and conservation of aquatic resources in both marine and freshwater environments. This includes oceans and seas, coastlines and banks, lakes, rivers and groundwater. The blue economy also encapsulates not only the economic benefits, but also addresses the needs and effects on the environmental and social aspects of these transactions [22]. The definition of Oceans Economy which has been adopted by South Africa isentrenched on the oceans as the geographical space of interest. South Africa shows a well-articulated commitment to develop its oceans economy. Turning to the imperatives of a blue economy, the latter is not explicit in South Africa’s focus on the ocean economy [23]. Vreÿ [23] examined documents associated with operation Phakisa to identify the blue economic commitment of ocean economy and he uncovered the absence of an overt blue economic rationale in the ocean leg of Phakisa. However, the architects of Oceans Phakisa argue that policy documents such as National framework for Marine Spatial Planning (of 26 May 2017) and Marine Protected Areas commits State departments and agencies of Phakisa to environment-sustainable nexus. Environmental groups argue that, oil and gas exploration is particularly incompatible with other uses of the ocean – such as fishing, ecotourism, and conservation – as the toxic pollution from cumulative operational oil spills or major spills (should there be a catastrophic wellhead blowout) will be carried by ocean currents and wind and will not respect spatial boundaries (such as declared marine protected areas or defined critical biodiversity areas) in the ocean’s fluid and dynamic environment [24]. South Africa’s option of ocean economy instead of blue economy seems to raise a question regarding environmental sustainability and the land sea interface.

Conflict of interest

The conflict of interest which this paper explores relates to the mandate that is associated with the department that drives oceans economy in South Africa, the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment. The discourse about conflict of interest is underscored by the following questions:

a) Does Ocean Phakisa’s economic agenda threaten the environment and the coastal ecosystem?

b) Shouldn’t the Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and Environment (DFFE) oversee protection of coastal ecosystems from possible risks associated with ocean economy, rather than lobbying for the commercialization of the coast?

In South Africa, oceans economy is implemented through oceans economy master plan which is the initiative of Operation Phakisa (Phakisa meaning ‘to hurry’ in Sesotho). Coordination of Ocean Phakisa was assigned to the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment by the cabinet of South Africa. Despite the potential of conflict of mandates, DFFE accepted the mandate to drive oceans economy which from its inception has a pure economic agenda. Ocean economy has recently gained widespread attention globally as a new economic frontier with the potential to boost economic growth and employment [25]. Ocean Phakisa was established in 2014 to stimulate oceans economy. When the Department presented in 2009/2010 on ocean policy to Cabinet, it was asked about the significance of the ocean. The Department commissioned an economic study in 2010 to determine the contribution of the ocean to the South African Economy, in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Jobs [26]. This approach expounds the fundamental conflicting point for the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment. The economic study was generally linked to GDP and job creation rather than natural capital approach which focuses on nature’s carrying capacity. The department is mandated by the constitution to ensure that everyone has the right to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well being as well as to protect the environment for the benefit of present and future generations. Professor Mandy Lombard, when presenting in the Portfolio Committee on Environmental Affairs [27], asked if the Department of Environmental Affairs is mandated to care for the environment, how it would balance economic objectives with environmental concerns, especially if the marine spatial Bill (MSP) Bill sits within it. One of the objectives of the Marine Spatial Planning Act [28], is to conserve the ocean for present and future generation and this is the direct mandate of DFFE. Often, marine conservation is likely to be in direct conflict with development initiatives of oceans economy.

Ocean Phakisa focused on the following areas: marine transport and manufacturing, offshore oil and gas, aquaculture and fisheries, coastal and marine tourism, and small harbours development. It is worth noting that some of the above-mentioned focus areas of oceans economy are in direct conflict with the core mandate of DFFE. Just as an example, environmental impact assessment which stem from chapter five of NEMA is constantly viewed as the red tape by the development proponents including ministries with the core mandate of economic growth. As the competent authority of the EIA processes, DFFE should not be conflicted thereby using the EIA processes to rubberstamp development at the expense of the environment. In fact, to fast track the offshore and gas exploration, Department of Mineral Resources rationalise the permitting system through a policy called One Environmental System [29]. This system removed the need to undergo EIA processes for offshore oil and gas seismic surveys. According to One Environmental System, Department of Mineral Resources is responsible for issuing environmental authorisation for mining companies rather than Department of Environmental Affairs. This is viewed as a conflict of interest by some environmental advocacy groups and civil society since this arrangement assigns environmental oversight function to a department which is mandated to promote mineral extractions. Furthermore, environmental groups argue that One Environmental System was propelled by influential and powerful economic players in mining and energy industry rather than environmental protection authorities. Lowering of standards to protect the environment does little to instil confidence that Phakisa’s oceans economy prioritises environmental concerns [23].

Another area of potential conflict between ocean Phakisa and DFFE is the marine protected areas. Marine protected areas are governed under the National Environmental Management: Protected Areas (NEMPA) (Act 57 of 2003) and Marine LivingResources Amendment Act 5 of 2014 by the government through the Department of Environment, Forestry & Fisheries (DEFF). South Africa’s Ocean, coastal and terrestrial zones are managed by the Department of Environment, Forestry & Fisheries (DEFF). The Department of Environmental Affairs manage these MPAs through a variety of management authorities, such as CapeNature, Eastern Cape Parks and Tourism Agency (ECPTA), Nelson Mandela Bay Metro (NMBM), South African National Parks (SANParks), Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, and iSimangaliso Wetland Park Authority (IWPA). In line with the international protocols the minister of Environmental Affairs has the obligation to expand marine protected areas (MPAs) to reach 10% coverage of South Africa’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). In fact, the Marine Protected Area Expansion strategy actually calls for 20%. 5% of South Africa’s Ocean (EEZ) is protected and About 90% of the oceans in South Africa’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) are under lease for oil and gas exploration or extraction [30]. Some of the features of ocean Phakisa such as of Oil and gas, fishing, coastal development is listed as some of the pressures which are a threat to marine ecosystem. In dealing with these pressures, DFFE is the main authority which has the mandate to defend and protect the environment without being conflicted by economic interest.

Valuing the ocean

To what extent does the ocean economy contribute to the country’s GDP? [31] This was a question which was interrogated by the initiators of ocean Phakisa. According to government of RSA [32], from the economic analysis of the total ocean sectors (in 2010), it was estimated that the oceans economy could contribute between R129 to R177 billion by 2033 and create between 800 000 to 1 million Jobs. However, in most instances the value proposition for oceans economy is mainly based on the ocean-based industries, excluding the value of the marine ecosystems. According to Kaiser & Roumasset [33] marine ecosystems encompass oceans, salt marshes and intertidal zones, estuaries and lagoons, mangroves and coral reefs, the water column including the deep sea, and the sea floor. Although measuring the value of marine ecosystems is a difficult and complex exercise [34], however, the agenda for the ocean economy should take nature’s value and carrying capacity into account. Similarly, the question about the cumulative effect of the ocean economy to the marine ecosystems is not adequately addressed in the Oceans Economy Master Plan of South Africa. According to the OECD [2] during the mid-1990s, ocean economic activity has surged, leading to both an unprecedented use of ocean resources and exponential development of new products to use the ocean. This continuing growth of the ocean economy, often outpacing the growth of the global economy, boosts economies and jobs but also increases environmental impacts, contributing to degrade further ocean health [2].

When assessing ocean Phakisa founding documents, it is apparent that the value proposition for oceans economy was mainly based on the output of economic growth and job creation. The economic model that was adopted to determine the economic value of the ocean is not clearly articulated. Masie & Bond [35] view ocean Phakisa’s model as reckless in relation to social justice, the environmental commons and meaningful economic empowerment. Tate et al. [36] submit that Phakisa’s ocean valuation methodology within the oft-quoted report by Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) marine economists calculates only the positive contribution of the ocean’s economy to ‘ecosystem services’ generated through ‘competitive markets. Some scholars have criticised Ocean Phakisa’s economically dominant, extractivism narrative, especially with regards to social injustices that are inflicted upon local coastal communities, indigenous people and small-scale fishers [37-40].

To differentiate between Blue and Ocean/Marine economy, Mcllgorm [41] introduce a concept of Total Economic Value (TEV), a framework used in environmental economics to value natural resources. According to this framework, goods are broadly classified into use value (from the use of the good), and non-use values (from not using the good). Use values are classified into direct values (values arising from the direct use of resources), indirect use values (values arising without degrading resources), and option values (values held for future use). Non-use value is classified into existence value (value arising from the existence of the resource) and bequest value (value arising from the use of the resource by future generations). It is apparent that the model used to calculate the value of the coast in South African Ocean Phakisa is not based on the Total Economic Value, therefore, there is a high risk that oceans economy in its current form might compromise future generations which is one of the constitutional guarantees in terms of section 24 of the RSA Constitution. Furthermore, natural capital shrinking due to extraction of non-renewable marine resources such as petroleum, gas and mineral resources is not duly considered when coastal valuation is conducted. although social and ecological impacts are acknowledged by Operation Phakisa, there has been critique regarding the initiative’s inability to effectively balance social, environmental and democratic values, and that economic objectives are narrowly calculated [42].

Marine spatial planning fragmentation

In South Africa, Marine Spatial Planning framework is regarded as the mechanism for ensuring multi- sector coordination and effective implementation of oceans economy. One of the objectives of the Marine Spatial Planning Act [43] is to provide for institutional arrangements for the implementation of marine spatial plans and governance of the use of the ocean by multiple sectors. The question is whether the Marine Spatial Act, has legitimacy and acceptancy among the planners and scientists alike as an authoritative framework over the marine space. The MSP lacks the overarching framework for ocean governance because of the lack of legislation for the National Environmental Management of the Oceans (NEMO) [44]. There is a statutory void in which the MSP is placed. The success of the marine spatial planning requires the involvement of multiple actorsand stakeholders at different governmental and societal levels. Based on its objectives, MSP also has a mandate over the ocean governance and the ocean is dynamic and fluid, meaning, it has a strong interface with the land. However, the land sea interface within the MSP is not clearly articulated and this create a gap.

One of the objectives of the Marine Spatial Act is to promote sustainable economic opportunities which contribute to the development of the South African ocean economy through coordinated and integrated planning. Governance and stakeholder engagement are key to effective ocean management, i.e., co-ordination across government as well as the engagement of all relevant stakeholders – scientists, business, user industries and associations – in the process [45]. For the promotion of good governance, the marine spatial planning framework of South Africa, commits to enable coordination with terrestrial and coastal planning as much as possible. However, in terms of institutional arrangements, the ocean governance proposed in the MSP is not in line with the principles of cooperative governance as espoused in chapter three of the constitution. Ocean governance is used loosely without considering principles of multiplicity, integration, and collaboration. According to CSIR [20] there appears to be concentration of power at the national sphere of government that is not indicative of a willingness to consider the critical role of provincial and local government; and civil society, including private sector, amongst others. Local government has a planning mandate especially over the terrestrial spaces. Inadequate consideration of local government clearly shows a lack of sea land interface.

The MSP proposed the following institutional arrangements, that is, director General committee on marine spatial planning and the ministerial committee on marine spatial planning. The MSP states that the Marine Area Plan boundaries will extend up to the high-water mark. According to the ICM Act, coastal municipalities are responsible for the coastal public property. The coastal public property also includes the high-water mark including the admiralty reserve. Therefore, disregarding local government in the MSP institutionalization and governance arrangements is counterproductive. Natural marine processes, ecosystems and species are not confined to maritime legal boundaries [46]. Park [47] defines ocean economy as the economic activities that take place in the ocean, receive outputs from the ocean, and provide goods and services to the ocean. The latter indicate that oceans economy cannot be limited to the marine space only, however there is strong interconnection between the land and the sea. Any planning framework which promotes oceans economy should have a strong land sea interface in order to ensure integration, cohesion and coordination.

Public participation and inclusivity

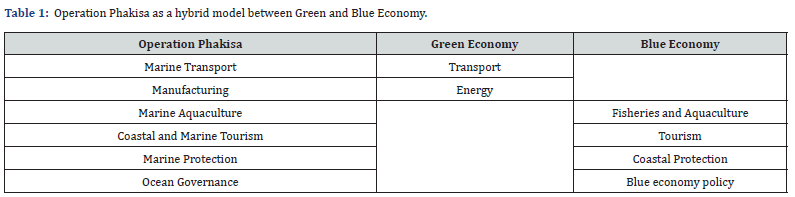

The success of ocean economy hinges on ocean governance structures and frameworks and the initiators of Ocean Phakisa proposed the following structure (Figure 1):

Marine Spatial Planning is an integral part of Ocean Economy. Public participation is a crucial element of coastal and marine planning for its long-term democratic legitimacy and sustainability [48]. Marine Spatial Planning has been described by the IOC (of the UNESCO) as a public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in maritime areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives that are usually specified through a political process [49]. To drive oceans economy South African government developed a Marine Spatial Planning Act (Act No 16 of 2018) to provide basis for marine spatial planning. However, the question is whether or not the public participation process was inclusive and satisfactory is fundamental since MSP is a public process which involve multiple stakeholders. Flannery and Healy argue that there is a growing concern that MSP is not facilitating a paradigm shift towards publicly engaged maritime management and that it may simply repackage power dynamics in the rhetoric of participation to legitimise the agendas of dominant actors. Making submissions at the Portfolio Committee on Environmental Affairs, SCIR [18], made assertions that the MSP was severely challenged in terms of consultation, oversight, and participation. Power seems to be concentrated at the national level of government, which does not seem to reflect a willingness to consider the important role those other stakeholders play. Therefore, the largest threat to the MSP’s success continues to be the lack of transparency, inclusiveness, and involvement. Just like the ocean Phakisa governance structure, the Marine Spatial Act, recognises the following structures:

a) National Working Group

A National Working Group on Marine Spatial Planning comprises of officials nominated from the departments of defence, energy, environmental affairs, fisheries, mineral resources, planning monitoring and evaluation, public enterprises, science and technology, telecommunications, tourism, transport, rural development and land affairs.

b) Directors-General Committee

A Directors-General Committee on Marine Spatial Planning includes Directors-General from the departments of defence, energy, environmental affairs, fisheries, mineral resources, planning monitoring and evaluation, public enterprises, science and technology, telecommunications, tourism, transport, rural development and land affairs

c) Ministerial Committee

The Ministerial Committee on Marine Spatial Planning comprises of Ministers responsible for defence, energy, environmental affairs, fisheries, mineral resources, planning monitoring and evaluation, public enterprises, science and technology, telecommunications, tourism, transport, rural development and land affairs

Land based problems (sewage and solid waste)

Coastal cities and towns are an integral part of oceans economy. However, urbanization problems such as estuary and coastal water pollution have a direct impact to oceans economy pillars such as aquaculture, coastal tourism, marine protected areas and coastal biodiversity. According to Mail & Guardian [50] South African cities have a serious sewerage problem. Due to their strategic location and existing infrastructure, coastal cities in South Africa will pay an important role in ocean Phakisa. However as shown in Table 2, all coastal cities of South Africa have a sewage problem which spill into estuaries and beaches. According to the Green Drop Report, 67.6% of the wastewater treatment works fail to adequately clean raw sewerage. The situation has been made worse by load shedding and natural disasters which took place in areas such as eThekwini metropolitan municipality. The interaction between land-based systems and ocean have the direct impact to oceans economy. For example, coastal run-off and eutrophication, acidification through increasing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and poor water quality through pollution lead to changes in fish migration patterns and even extinction of fish stocks [2]. Furthermore, polluted beaches undermine coastal tourism and compromise jobs and the economy.

Source: Author.

Poor solid waste management is another land-based problem which will jeopardise oceans economy ambitious targets. Leon Grobbelaar, a former president of the Institute of Waste Management of Southern Africa, says SA’s landfills are in a “terrible state; the worst they have been in decades” [55]. Municipalities throughout the country are facing crises of solid waste disposal and management. Poorly managed solid waste ultimately ends up in rivers which carry a great deal of plastic waste from land intothe sea [56]. According to Li et al. [57] up to 80% of marine plastic debris is from land-based sources. According to Mani et al. [58] the Durban area in South Africa is particularly impacted by those challenges. Naidoo [59] found that urban area of Durban was responsible for the high levels of plastic particles found in most estuaries along the coastline of Durban. Five rivers, including the Umgeni River, carry an annual combined 1,340 tons of plastic waste towards the Indian Ocean leading to vast accumulations of particulate matter pollution on Durban’s beaches. The uMngeni River and Estuarine System is considered as one of the most polluted riverine systems in South Africa and a major contributor of plastic waste entering the Indian Ocean [60,61]. Plastic waste poses a serious threat to marine species such as fish, seals and turtles which are often entangled by the plastic or sometimes mistake the plastic waste as food and ingest its material [62]. Marine pollution is worsened by heavy rains and flash floods which carry loads of debris into the estuaries and ocean, affecting ports operations and the economy (see Figure 2).

Concluding Remarks and Recommendations

This study succeeded in advancing a problematic discourse about Ocean Phakisa which is a blue economy model of South Africa. This was done through document analysis by critically analysing the conceptualisation and institutionalization of Ocean Phakisa. When Operation Phakisa was launched, ocean economy was viewed as the programme to grow the economy and create jobs. Economic growth was the main purposes for government of South Africa to initiate Ocean Phakisa. The ocean was viewed as a good business opportunity to exploit in order to grow the economy. Even though South Africa was part of the UN Conference on Sustainable Development which was held in Rio de Janeiro in 2012 which reinforced the blue economy concept, South Africa chose a different concept that, is, the ocean economy. This approach by South African government creates uncertainty regarding environmental sustainability outlook of Ocean Phakisa model as well as inclusivity. To avoid uncertainty, South Africa should align itself with Africa’s blue economy Policy and the rest of the world by adopting the concept of blue economy. Furthermore, South Africa’s blue economy should be entrenched in the national legislation which seeks to embrace the land sea interface. Currently, Ocean Phakisa is driven through Ocean Economy Master Plan of 2030. However, the masterplan failed to garner support from broader stakeholders and it is not anchored to any piece of legislation that is specific on blue economy, except sector legislation. South Africa should align itself with the concept of blue economy because the ocean development should take into consideration economic growth, equitable beneficiation and ecosystem health. The definition of oceans economy should not only include the ocean-based industries but also the natural assets and ecosystem services that the ocean provides.

South Africa’s Ocean economy was benchmarked from the Malaysia’s Big Fast Results Methodology. However, deviation from the benchmarked strategy in an effort to contextualize the implementation is one of the benchmarking problems. In Malaysia, the Government Transformation Programme (GTP) was located in the Prime Minister’s office to ensure effective implementation, avoid conflicts of interest, and establish authority. However, the South African cabinet assigned the role of coordinating ocean economy to the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. This has compromised both the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment in terms of its mandate and the implementation of ocean economy. DFFE commissioned an economic study to determine the economic value of the ocean, rather than a study to determine the capital value of the ocean ecosystem in line with their mandate. Although environmental economics is a discipline within environmental management, however, DFFE has a specific mandate, which is environmental protection. This study recommends that South Africa’s Ocean Phakisa in its current form should be housed in the office of the President. This will ensure proper coordination and avoid conflict of interests.

Inadequate involvement of different stakeholders such as local government undermines the efforts of ensuring sustainable ocean economy. Municipalities play a critical role in the land sea interface through planning and services. Poor municipal planning and service delivery can undermine ocean economy initiatives. The overarching framework of ocean economy should include coastal municipalities in planning and governance arrangement. Therefore, it is imperative that city planners participate in the ocean economy, where the objectives of the marine sector and urban planning are intertwined. Effective waste management practices are necessary for the ocean economy to succeed because coastal cities serve as a land-sea interface. Municipalities are essential to the ocean economy because of their unique and shared roles in infrastructure, public services, economic growth, transportation, health, and environmental management. Unless the government localizes the ocean economy, resistance from local actors will persist and impede implementation. The ocean economy should engage not only industry participants and national governments, but also local communities, to ensure that the benefits are equitable. The Constitution of RSA assigns local government with a responsibility to promote social and economic development in their localities. To create more economic opportunities, cities should rethink local economic development and incorporate green and blue economic aspects. A localised ocean economy should give rise to blue Small, Medium, and Micro Enterprises (SMMEs) who play an active role in sectors such as marine renewable energy, shipping, fisheries and aquaculture, coastal tourism and marine biotechnology. Meaningful awareness and capacity building initiatives, particularly among the formerly underprivileged regions, should support this localization of the ocean economy.

Increasingly, it is acknowledged that the sectoral approach within the ocean space fails to optimize economic opportunities and safeguard environmental protection. In order to address this shortcoming, government gazetted National Environmental Management of the Ocean White Paper of 2014. The White Paper contends that over the next five years South Africa will transition from the current sector-based ocean management approach to a coordinated cross-sectoral planning scheme. However, in 2008, the Integrated Coastal Management Act was also proposed as a solution to tackle the problem of fragmentation and lack of coordination in coastal landscapes and seascapes. Given that both legislations are under the jurisdiction of DFFE, it is imperative to seek public consensus about their distinct purposes and interconnectedness.

Government should embrace a principle of holism that ensure a meaningful implementation of the source to sea management strategies. The water cycle links land, freshwater, coastlines, and the ocean; consequently, activities taken in a single area can have ripple effects in other parts of the cycle. Currently section 69 of the ICM Act (2008) regulate the discharge of effluent that originate from a source of land into coastal waters. The National Water Act, 1998 (Act 36 of 1998) regulate the disposal of affluent into freshwater systems. In addition, environmental health inspectors are required to investigate factors that contribute to water pollution and other health risks according to Section 83 of the National Health Act (61 of 2003). Currently the wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) from municipalities are not in good standing and poor waste management results to pollution into rivers and sea. However, compliance mechanisms and intergovernmental relations interventions are not yielding any positive results. There is a need to come up with a singular legislative framework which will address the source to sea pollution.

References

- United Nations (2022) Blue Economy: Oceans as the next great economic frontier.

- OECD [The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] (2016) The Ocean Economy in 2030, Paris: 2016.

- Ismail AA (2022) The role of institutions in supporting coastal communities at risk from climate change: A case study of Buffeljagsbaai, South Africa. Faculty of Science, Department of Environmental and Geographical Science.

- Walker T (2018) Securing a sustainable ocean economy: South Africa’s approach. Institute for Security Studies. Pretoria, South Africa.

- Struwig M, Van den Berg A, Hadi N (2023) Challenges in the ocean economy of South Africa. Development Southern Africa 41(1): 1-15.

- Fischer C (2006) Research Methods for Psychologists: Introduction through Empirical Studies. USA, Elsevier Inc.

- UNRIC (2022) Green Economy: A Path Towards Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication.

- UNEP (2016) Blue Economy Concept Paper.

- UNEP (2016) Green Economy in a Blue World: Synthesis Report.

- Smit C (2024) A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Blue Economy with Specific Reference to South Africa. Stellenbosch University

- Mann-Lang JB, Branch GM, Mann BQ, Sink KJ, Kirkman SP, et al. (2021) Social and economic effects of marine protected areas in South Africa, with recommendations for future assessments. African Journal of Marine Science 43(3): 367-387.

- (2014) The Presidency, Republic of South Africa. Operation Phakisa – Oceans Economy.

- Rethabile Melamu (2020) The green economy – a win-win strategy for South Africa. Mail & Guardian.

- Zulu BC, Zondi BW, T Ngwenya (2023) Challenges faced by SMMEs operating in the ocean economy in KwaZulu-Natal province: A quantitative study. SAJESBM 15(1).

- Daly E, Singham S (2011) Jump-starting Malysia’s grown: An interview with Idris Jala. McKinsey Quarterly, McKinset & Company.

- Ram J, Jeffery DK, Hope K, Peters A, Durant I (2017) Implementation: Delivering Results to Transform Caribbean Society. Economics Department of the Caribbean Development Bank.

- Malaysia’s Government Transformation Programme (GTP) (2010) Progress of the Government Transformation Programme Perspectives from the top. Jabatan Perdana Menteri Annual Report 2010.

- Siddiquee NA (2014) Malaysia’s government transformation programme: A preliminary assessment. Intellectual Discourse 22(1): 7-31.

- Parliament of the Republic of South Africa (2020) Operation Phakisa: Aquaculture, Small Harbours, Marine Protection Services, And Ocean Governance.

- Kildow DJT, Judith T (2021) Preparing a Workforce for the New Blue Economy: The importance of the new blue economy to a sustainable blue economy: an opinion. Working Papers

- The National Ocean Economics Program, NOEP (2020).

- Voyer M (2017) (Commonwealth of Australia) The Blue Economy in Australia

- Vreÿ F (2019) Operation Phakisa: Reflections Upon an Ambitious Maritime-Led Government Initiative. Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies 47(2).

- The Green Connection (2023) Marine spatial plan flawed because oil and water do not mix.

- Scandizzo PL, R Cervigni, Ferrarese C (2018) A CGE Model for Mauritius Ocean Economy. In: F Perali, PL Scandizzo (Eds.), In the New Generation of Computable General Equilibrium Models. New York: Springer, pp. 173-203.

- Briefing to the Portfolio Committee on Environmental Affairs (2017) Hearing on the Marine Spatial Bill. South Africa.

- The Portfolio Committee on Environmental Affairs (2017) Ocean Economy Colloquium, Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environmental Affairs.

- Marine Spatial Planning Act (2018) (No. 16 of 2018).

- Solomon JM (2023) In the wake of ancestors, Dreaming of a Sacred Sea: Beyond the Battle against the Oil and gas Phakisa Imaginary. African Journal Alternation 30(1).

- Fearon G, Laing R, Bracco A, Reich D (2023) An oil spill model for South African waters. Trajectory and fate analysis of deep-water blowout spill scenarios.

- Potgieter T (2018) Oceans economy, blue economy, and security: Notes on the South African potential and developments. J Indian Ocean Reg 4(1): 49-70.

- Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment (2020) Towards a South African Oceans Economy Master Plan (Draft V3.0), Draft Discussion Document.

- Kaiser B, J Roumasset (2002) Valuing indirect ecosystem services: The case of tropical watersheds. Environment and Development Economics 4: 701-714.

- OECD (2016) The Ocean Economy in 2030, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Masie D, Bond P (2018) Eco-capitalist crises in the ‘blue economy’: operation Phakisa’s small, slow failures, in the book, The Limits of Capitalist Solutions to the Climate Crisis by Dorothy Grace Guerrero. Wits University Press.

- Tate D, Haines R, Hosking S, Kaczynski W, Thou G, et al. (2012) Development of the Methodology for Identifying and Assessing the Economic Contribution to the South African Economy of the Goods and Services [Ecosystems and Biodiversity] Yielded bythe Oceans and Coasts Environment. School of Economics, Development Studies and Tourism, Faculty of Economics and Business Sciences. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, report prepared for the Department of Environmental Affairs

- Boswell R, Thornton JL (2021) Including the Khoisan for a More Inclusive Blue Economy in South Africa. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 17(2): 141-160.

- Isaacs M, Hattingh J (2022) Activist Litigation as Form of Social Innovation to Transform Governance for Small-Scale Fisheries in South Africa. Presentation at 4WCSF.

- Le Fleur Y, Nangle M, Mannarino C (2023) Resisting the Waves of Ocean Grabbing: Challenges, Priorities and Strategies in the Small-Scale Fishers’ Governance Struggle Against the Ocean Economy in South Africa. Development, pp. 1-7.

- Solomon J (2023) In the Wake of the Ancestors, Dreaming of a Sacred Sea: Beyond the Battle Against the Oil and Gas Phakisa Imaginary. Alternation 30(1): 72-102.

- McIlgorm A (2016) Ocean Economy Valuation Studies in the Asia-Pacific Region: Lessons for theFuture International Use of National Accounts in the Blue Economy. of Ocean and Coastal Economics 2(2).

- Masie D, Bond P (2018) Chapter 15: Eco-Capitalist Crises in the ‘Blue Economy’: Operation Phakisa’s Small Slow Failures. In: V Sagtar (Ed.), The Climate Crisis: South African and Global Democratic Eco-Socialist Alternatives. Wits University Press, pp. 314-335.

- Republic of South Africa. Marine Spatial Planning Act, 2018 (No. 16 of 2018).

- Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) (2017) Briefing to the Portfolio Committee on Environmental Affairs Public Hearings on the Marine Spatial Planning Bill (B9-2017).

- Lukambagire I, Matovu B, Manianga A, Bhavani RR, Anjana S (2024) Towards a collaborative stakeholder engagement pathway to increase ocean sustainability related to marine spatial planning in developing coastal states. Environmental Challenges 15: 100954.

- OECD (2016) The Ocean Economy in 2030, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Park KS (2014) A study on rebuilding the classification system of the ocean economy. Center for the Blue Economy in Monterey Institute of International Studies, Monterey, California.

- Wilke M (2023) Comparing Public Participation in Coastal and Marine Planning in the Arctic: Lessons from Iceland and Norway. Coasts 3(4): 345-369.

- Ehler C, Douvere F (2009) Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by Step Approach Towards Ecosystem-based Management. Manual and Guides No 153 ICAM Dossier No 6. Paris: Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission UNESCO IOC, p. 99.

- Patel O (2024) Myriad causes of SA’s water crisis. Mail & Guardian.

- News24 (2023).

- Herald Live (2022).

- Daily Maverick (2023).

- IOL (2023).

- Wadula P (2022) No more space for SA’s waste. SA is running out of room to dump millions of tons of garbage. Business Live.

- Ryan P (2018) Plastic pollution update. African Birdlife.

- Li W, Tse HF, Fok L (2016) Plastic waste in the marine environment: A review of sources, occurrence and effects. Sci Total Environ 566-567: 333-349.

- Mani T, Gutsa T, Khan M, Lebreton L, Trois T (2021) CAPTURE – Climate Change Adaptation amid Plastic Waste Transport in the Umgeni River Environment. Proceedings SARDINIA2021.

- Naidoo T (2018) Microplastic concentration on the urban coastline of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa and it’s impact on juvenile fish. University of KwaZulu Natal, School of Life Science.

- Carnie T (2013) Umgeni River ‘one of dirtiest’in South Africa.

- Naidoo T, Glassom D, Smit AJ (2015) Plastic pollution in five urban estuaries of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Marine Pollution Bulletin 101(1): 473-480.

- Mkhize S (2020) Impacts of Plastic Pollution on our Marine Economy and Environment.

- Aldersley M (2019) Alarming footage shows South African port swamped in plastic waste and debris after heavy rain and flash flooding.