Abstract

This paper examines the operationalization of Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs) in Asia, highlighting their transformative potential for achieving inclusive biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and sustainable development goals. It also emphasizes the potential of OECMs to advance the reporting of Target 3 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KM-GBF), showcasing their role in advancing integrated, area-based conservation approaches across diverse ecosystems. Drawing on over a decade of collaborative efforts facilitated by the Asia Protected Areas Partnership (APAP), especially focusing on OECMs since 2023, the study synthesizes insights from national dialogues in Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam, Sri Lanka and the Republic of Korea, along with an APAP regional workshop on OECMs in Japan. It identifies key challenges in governance, spatial integration, and monitoring and proposes actionable solutions tailored to the region’s socio-political and ecological contexts. Emphasizing the integration of participatory governance models, advanced monitoring frameworks, and cultural and socio-economic values, the paper situates areas reporting as OECMs as pivotal towards enhancing ecological connectivity and fostering inclusive conservation strategies. By aligning global guidance with regional, national, and local realities, this study provides a roadmap for effectively operationalizing OECMs in Asia and beyond.

Keywords: OECMs; Biodiversity conservation; Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework; Spatial planning; Participatory governance

Introduction

The global conservation community increasingly acknowledges OECMs as a critical complement to protected areas in biodiversity conservation [1,2]. Initially introduced as part of the Target 11 of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets of the Strategic Plan of Biodiversity 2011-2020, and subsequently defined by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) at the 14th Conference of the Parties as “a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity,” OECMs extend conservation benefits to include associated ecosystem functions, services, and locally relevant cultural, spiritual, and socio-economic values [3]. Invited by the CBD to provide guidance to CBD Parties, the IUCN has played a significant role in conceptualizing and advancing OECMs within global conservation policy, particularly through the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA). The IUCN WCPA has been instrumental in developing the OECM guidance and toolkit, in addition to technical support to help countries identify, recognize, and report OECMs as part of their national conservation strategies. By ensuring that areas delivering effective conservation outcomes—whether through diverse governance such as led by Indigenous peoples, local communities, sustainable resource management bodies, or private conservation initiatives—are acknowledged within the global biodiversity framework, IUCN and the IUCN WCPA have facilitated the mainstreaming of OECMs into conservation planning.

OECMs are expected to play a crucial role in advancing the targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, particularly Target 3, which calls for conserving at least 30% of the planet’s land and sea areas by 2030 [4]. By recognizing areas outside protected areas networks that deliver effective biodiversity outcomes, OECMs contribute to the achievement of this ambitious target [5-7]. The proper identification and strategic distribution of OECMs can strengthen ecological connectivity and sustain critical ecosystem services in areas of highest ecological significance. Additionally, recognizing and effectively managing OECMs has the potential to provide inclusive solutions that integrate local communities and accommodate diverse governance models [8]. This alignment underscores the importance of OECMs as essential tools for achieving global conservation goals while addressing socio-economic and cultural dimensions of biodiversity conservation and management at the national, regional, and global level [9].

Despite their potential, OECMs remain underutilized due to the limited common understanding and capacity needed by governments and civil society stakeholders for their identification, governance recognition, and integration into national broader conservation strategies, including domestic laws and policies. The IUCN-WCPA emphasizes that OECMs should be recognized and reported based on their conservation outcomes, regardless of their primary management objective [10,11]. These recognized OECMs hold significant potential to enhance ecological connectivity, protect critical ecosystems, and contribute to landscape and seascape conservation [12].

This paper delves into these unresolved issues, examining the pathways through which OECMs can be effectively operationalized. By leveraging insights gained from national dialogues as well as regional workshops in Asia since the adoption of the KM-GBF in 2022, it identifies actionable solutions for addressing governance complexities, enhancing spatial integration, and strengthening monitoring mechanisms. These solutions emphasize participatory governance models, advanced data reporting frameworks, and the strategic integration of OECMs into broader conservation of landscapes and seascapes. Furthermore, the analysis underscores the transformative potential of OECMs to address multifaceted environmental, social, and economic challenges, aligning them with global biodiversity targets and sustainable development goals. Through the practical approach of OECMs dialogues, the paper situates OECMs as a pivotal mechanism for fostering resilience and connectivity across ecosystems while supporting equitable and inclusive conservation strategies to further secure biodiversity conservation.

Methodology

This paper represents the culmination of over a decade of collaborative efforts facilitated through the Asia Protected Areas Partnership (APAP). APAP is a regional platform that enhances collaboration, knowledge exchange, and capacity-building among conservation stakeholders in Asia. It promotes best practices in protected and conserved area management and supports international commitments like the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). Recognizing the importance of inclusive conservation, APAP highlights OECMs as key to achieving GBF Target 3, ensuring biodiversity conservation extends beyond protected areas into sustainably managed landscapes and seascapes. APAP has worked on policy matters including a regional workshop on OECMs held in Tokyo in 2024 to provide strategic guidance for this study [13]. Through its initiatives, national dialogues on OECMs were organized in countries such as Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam, the Republic of Korea and Sri Lanka. The country experiences including the national dialogues brought to the regional workshop held in Japan, served as a critical forum for synthesizing regional perspectives and identifying shared challenges and opportunities.

The research process involved extensive consultations and discussions with partners across Asia, including policymakers and conservation practitioners. These consultations were designed to identify key barriers and solutions related to the identification, recognition, and operationalization of OECMs. The paper draws on insights from APAP meetings, field-based case studies, and thematic analyses of governance, spatial planning, and monitoring frameworks. By integrating these diverse perspectives, the study provides a comprehensive examination of OECM implementation challenges and offers actionable recommendations tailored to the Asian context.

Integration into Spatial Planning

OECMs are instrumental in maintaining ecological connectivity and conserving functional ecosystems beyond conventional protected areas [14]. Integrating OECMs into national and potentially to regional spatial planning frameworks ensures these measures contribute to broader terrestrial and marine conservation goals, enhancing resilience and ecological integrity at multiple scales [15-18].

To optimize integration, national spatial plans should prioritize OECMs as key components of conservation networks [9]. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) play a pivotal role in identifying and mapping OECMs, enabling policymakers to visualize ecological connectivity and prioritize protected areas and OECMs for conservation [19]. Spatial planning should also help policymakers in addressing land-use conflicts, ensuring that biodiversity conservation aligns with economic and social development goals [20].

Furthermore, OECMs can serve as strategic buffers and steppingstones that connect fragmented landscapes. By incorporating OECMs into urban and rural development policies, planners can enhance biodiversity corridors, especially in regions experiencing rapid industrialization and infrastructure expansion [21,22]. Collaborative planning approaches involving multiple stakeholder-local communities, private sectors, and government agencies—are essential to ensure the ownership and accountability necessary for effective implementation [23].

Marine OECMs play a vital role in marine conservation by recognizing and supporting areas that achieve effective conservation outcomes outside conventional protected area frameworks [17,24]. Integrating marine OECMs into spatial planning is essential for addressing gaps in marine biodiversity conservation, ensuring connectivity between protected areas, and strengthening ecological resilience in the face of climate change and other threats. However, several challenges hinder their effective identification, designation, and integration into national and regional conservation strategies.

A primary challenge in the marine realm is the significant gap in baseline ecological, social, and economic data, which limits the ability to identify, map, and monitor areas with high conservation value. Addressing this requires investment in high-quality data collection and leveraging remote sensing, geographic information systems, and marine spatial planning tools to improve the identification and long-term monitoring of OECMs [25]. Additionally, the dynamic and interconnected nature of marine ecosystems, where species and ecological processes often transcend national boundaries—such as migratory species with extensive ranges—complicates the delineation of OECM boundaries and the assessment of consistent conservation outcomes. To ensure ecological resilience and support species migration, OECMs must be integrated within broader networks of protected and conserved areas, with adaptive spatial planning approaches that respond to evolving ecological and socioeconomic conditions.

The overlapping of multiple sectoral activities, including fishing, shipping, and tourism, further complicates the designation and management of marine OECMs. A participatory and multisectoral approach is essential to align conservation objectives with sustainable resource use and ensure that marine OECMs contribute meaningfully to biodiversity goals [25]. Furthermore, many countries lack clear policies and legal frameworks to formally recognize marine OECMs, integrate them into national reporting systems, and embed them within spatial planning processes. Strengthening policy mechanisms and governance structures will be critical to maximizing the potential of OECMs in marine conservation.

Given the increasing recognition of marine OECMs in Asia, it is essential not to overlook their foundational elements, such as robust data collection, cross-sectoral engagement, and legal recognition. Country-level examples could provide valuable insights into how these challenges are being addressed and how marine OECMs can effectively contribute to biodiversity conservation and the achievement of Target 3 of the Kunming- Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework [17,24].

In general, challenges remain in defining and implementing OECMs effectively, including aligning them with global definition and standards. After the CBD-COP14 decision 14/8 was adopted, IUCN WCPA has prepared a global standard [26]. However, the global standard is not designed for the adaptive use at regional and national context. The management of OECMs requires robust monitoring and reporting mechanisms. OECM recognition faces resistance in some contexts due to stakeholders’ unfamiliarity and concerns over potential land-use restrictions, displacement, or conflicts—challenges historically associated with protected area expansion. In regions with complex land tenure systems, fears of losing autonomy or increased regulation further contribute to hesitancy. Additionally, some government agencies and conservation practitioners question OECMs’ long-term effectiveness, governance, and monitoring, as they exist in multi-use landscapes where biodiversity conservation must be balanced with economic activities like agriculture, fisheries, and tourism. Ensuring sustainable conservation outcomes without undermining livelihoods remains a key challenge.

The Sundarbans, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Bangladesh, integrates OECMs into national spatial planning by designating buffer zones for sustainable resource use. These zones maintain ecological connectivity and support the livelihoods of local communities. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have been employed to identify and map these areas, ensuring alignment with biodiversity conservation goals while addressing land-use conflicts [27,28].

China has delineated Ecological Red Lines (ERLs), which refers to the areas where ecological functions are important and fragile, with significant ecological value. Take Fuzhou’s Ecological Red Lines (ERLs) as an example: it integrates mountain-sea ecosystems, covering 5,082.05km², including 1,008km² of protected areas. They span native forests, estuarine wetlands, river zones, and mountain-sea corridors. Managed by the Fuzhou Municipal Bureau, the program enhances connectivity and biodiversity through scientific research, spatial planning, and conservation measures like mangrove restoration and ecosystem monitoring. By integrating land and marine efforts, Fuzhou’s ERLs demonstrate the value of strategic planning, innovation, and collaboration for sustainable conservation [29].

Thailand has developed national criteria aligned with the CBD definition as well as IUCN WCPA criteria. Based on the national criteria, Thailand has identified potential OECM sites such as the Lower Songkhram River Basin, Nakhon Phanom (Ramsar site), and the Toyota Biodiversity and Sustainability Learning Center in Chachoengsao, owned by Toyota Motor Thailand Co., Ltd. [13].

In Bangladesh, the Forest Department has been developing a national programme on OECMs in collaboration with various stakeholders since CBD COP 15. Under the SUFAL Innovation Grant Program of the Bangladesh Forest Department, Arannayk Foundation, an NGO, undertook a project to facilitate the establishment of a national mechanism for OECMs and to identify at least 45 OECMs in Bangladesh for national recognition and reporting [13].

The Republic of Korea has developed the K-OECM Toolkit, aligning with the CBD criteria outlined in Decision 14/8 and the IUCN guidelines to establish a systematic national approach. The 5th National Biodiversity Strategy (2024-2028) incorporates relevant provisions and outlines plans to create the necessary conditions for identifying OECMs. As part of this effort, the Republic of Korea has identified approximately 30 potential OECM types, which generally align with the OECM concept. These include “Conservation Properties,” “Conservation Agreements,” “Buffer Zones of World Natural Heritage Sites,” “Temple Forests,” and “Green Belts” (restricted development zones), among others [30]. Nepal is in the process of drafting a national guideline on OECMs [31], as well as India.

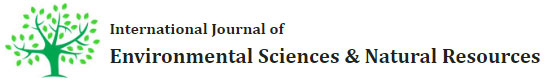

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of selected OECMs across different Asian countries, highlighting their ecosystem contexts, spatial planning approaches, and conservation outcomes. These cases illustrate how OECMs are integrated into broader landscape and seascape planning, contributing to biodiversity conservation, ecological connectivity, and sustainable resource management. The comparison underscores the diverse governance mechanisms and planning strategies used to ensure OECMs effectively complement protected areas while addressing national and regional conservation priorities.

Reporting and Monitoring OECMs

Robust reporting and monitoring mechanisms are essential for consistent and accurate data collection and representation [32]. Aligning reporting protocols with the United Nations Environment Programme - World Conservation Monitoring Centre’s (UNEP-WCMC) World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA-OECMs) ensures global consistency and comparability. National reporting should follow CBD cycles, typically every 4-6 years, with interim updates to reflect dynamic changes in OECM statuses [33,34].

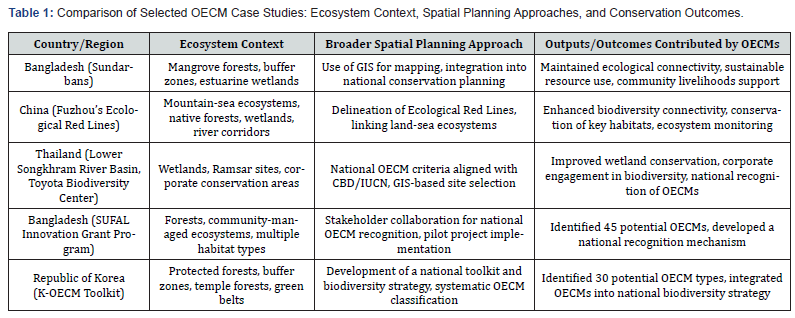

A critical challenge in reporting OECMs relates to the sovereignty of data, particularly when areas such as Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IP&LCs) territories or military zones are designated as OECMs. Many IP&LCs territories contain sensitive cultural information, while military zones often involve restricted access due to national security concerns. To address these issues, governments should collaborate with IP&LCs and the government agencies in charge of national defense to establish protocols that ensure the identification and protection of sensitive data while enabling effective reporting. For example, anonymizing data on boundaries or implementing controlled access policies can help balance transparency with security and sovereignty considerations (Figure 1).

Further complicating matters are the divergences between federal and provincial or state-level priorities. In general, countries with decentralized governance systems, discrepancies in conservation priorities can result in inconsistent reporting. Establishing a central authority responsible for coordinating OECMs reporting across administrative levels—in consultation with local stakeholders—can mitigate these challenges [35]. Finally, defining who reports to the WD-OECM (e.g., national agencies versus regional bodies) is essential to ensure accountability and clarity in the reporting process, along with a simplified data reporting format in the WD-OECM.

The Republic of Korea has developed a government-wide integrated protected area database (KDPA) through the Ministry of Environment, in collaboration with the Korea Protected Area Forum (KPAF). This database is regularly reported to the WDPA, and the same process is being applied to OECM recognition and reporting.

Regional CBD Technical and Scientific Cooperation Centres can play a critical role in standardizing data collection, validation, and quality assurance across countries in collaboration with UNEPWCMC and national governments. These centres can also facilitate capacity-building initiatives, equipping national agencies with the technical expertise needed for accurate reporting [36,37].

To further enhance monitoring system, advanced remote sensing technologies and citizen science platforms could also be employed. These tools may offer innovative cost-effective, realtime solutions for tracking biodiversity outcomes and ecosystem health in OECMs. Moreover, integrating artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques can potentially improve data analysis, helping to identify trends and inform adaptive management practices.

Vietnam’s Cu Lao Cham-Hoi An Biosphere Reserve incorporates OECMs into its monitoring framework by using citizen science platforms to gather data on marine biodiversity. Collaborative efforts between local communities and conservation agencies address sovereignty concerns, particularly in reporting data on fishing zones. This participatory approach ensures compliance with CBD reporting requirements while safeguarding sensitive information.

A stocktaking report on OECMs in China [29] introduces the general concept and categories of OECMs, summarizes relevant policies and the legal framework, and presents case studies. However, challenges remain, particularly regarding unclear responsibilities among government agencies and the need to balance top-down and bottom-up approaches, especially in the reporting and monitoring of OECMs in China.

Governance Structures

Effective governance frameworks tailored to OECMs’ diverse contexts are crucial. Governance must recognize the unique ecological, social, and cultural characteristics of each OECM while ensuring alignment with broader conservation objectives. Collaborative governance models that engage the landowners including sub-national governments, private sector, NGOs as well as IP&LCs and other rights holders ensure inclusivity and transparency for the adequate management of OECMs, [38,39].

Governance structures should classify OECMs based on their management objectives—primary, ancillary, or secondary. Each category requires distinct criteria for conservation commitment, operational accountability, and longevity [10]. Primary OECMs often involve stringent protection measures, while ancillary OECMs may require adaptive management strategies to balance conservation with other land-use priorities.

For the private sector, systematic certification systems, financial and tax incentives, and a supportive legal framework could be instrumental in actively engaging businesses in the establishment, management, and reporting of OECMs.

For IP&LCs-managed OECMs, formal agreements, comanagement arrangements, and secure land tenure systems are essential to ensure long-term conservation outcomes [40]. Capacity-building initiatives that empower IP&LCs with technical, legal, and financial resources are crucial for fostering effective governance [41,42]. Strengthening governance structures through participatory approaches can also enhance conflict resolution mechanisms, ensuring equitable decision-making processes. A simplified free prior informed consent (FPIC) process for OECMs may be customized to address local communities’ concerns and to promote enhanced community inclusion in the OECMs identification and management frameworks.

Application of participatory governance models that involve all relevant stakeholders are encouraged to ensure transparency and inclusivity, which are essential for the long-term success of OECMs [43,44]. This approach recognises the diverse contexts in which OECMs operate and allows for flexibility in governance while maintaining conservation outcomes [45].

Conservation efforts in Cheorwon Crane Land, recognized as an OECM in the Republic of Korea, represent a collaborative initiative between local farmers and various organizations, including the National Nature Trust and the Cheorwon Crane Protection Association, to safeguard endangered crane habitats. These efforts have significantly boosted crane populations through sustainable agricultural practices, ecotourism, and community-led conservation initiatives. The National Nature Trust plays a central role in managing conservation assets like Cheorwon Crane Land, supported by legal frameworks and financial mechanisms. This integrated approach not only enhances ecological preservation but also fosters local economic development, exemplifying a successful conservation model that balances human and wildlife interests [46].

Nepal’s Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) exemplify effective governance for OECMs, where local communities manage forest resources under formal agreements with the government. These groups employ participatory governance models to ensure inclusivity and equitable decision-making. Secure land tenure and co-management arrangements have strengthened long-term conservation outcomes while empowering local stakeholders [47].

Japan introduced its formal national OECMs certification system in 2023. 184 sites were certified as “Nationally Certified Sustainably Managed Natural Sites” as of February 2024. The certified cites have been registered on the WD-OECM as Japan’s first set of OECMs, spanning 48,000 hectares which excludes overlaps with protected areas. Japan’s national criteria for OECMs have been prepared based on the IUCN’s guidance for OECMs [13].

Table 2 provides a comparative overview of different OECM governance structures, categorizing them into Indigenous Peoples & Local Communities (IPLCs), private sector, sub-national governments, NGO & trust-managed OECMs, and multi-stakeholder collaborative governance. It highlights key governance features, real-world case examples, and the challenges associated with each governance type. The comparison underscores the diverse approaches to OECM management and the need for tailored governance frameworks that balance conservation objectives with socio-economic and policy considerations.

Enabling Policies and longevity of OECMs

Mainstreaming OECMs through enabling policies ensures their resilience and adaptability in dynamic conservation landscapes [20]. Flexible policies accommodate evolving conservation insights and allow for adaptive management approaches [48,49]. Such policies are particularly valuable in addressing unforeseen challenges, such as climate change and socio-economic shifts [50].

To secure the longevity of OECMs, it is vital to establish clear legal and institutional frameworks. Ancillary and secondary OECMs—often managed by private entities or IPLCs—may require targeted incentives, such as tax breaks, capacity-building grants, or technical assistance, to sustain conservation commitments over time [51,52]. Policy frameworks should also include provisions for monitoring compliance and evaluating the effectiveness of management practices to adapt to changing circumstances.

The Republic of Korea has enacted policies to protect cultural heritage forests, many of which qualify as OECMs. Tax incentives and grants for private landowners encourage sustainable management practices. Legal frameworks ensure these forests are preserved against urban development pressures, enhancing their ecological and cultural significance over time [53]. The Republic of Korea is revising the Act on the Conservation and Use of Biodiversity to systematically establish an OECM management framework. This includes defining key concepts, identifying potential sites, outlining registration procedures, and forming a consultative body to support implementation.

In Japan, “the Act on Promoting Activities to Enhance Regional Biodiversity” law was enacted in April 2024 to further promote voluntary activities by the private sector and other stakeholders who contribute to the establishment and management of OECMs [13].

OECMs as Nature-Based Solutions

OECMs contribute significantly to climate resilience and disaster risk reduction by preserving ecosystems that provide essential services, such as carbon sequestration, flood control, and storm protection [54,55]. Positioning OECMs as integral components of national and regional climate adaptation strategies enhances their relevance and funding prospects [16,56]. This approach aligns with the growing recognition of nature-based solutions in addressing biodiversity loss and climate change [11,57]. However, this dual role also necessitates that OECMs are supported by robust policy frameworks and adequate funding, particularly from climate finance mechanisms [58].

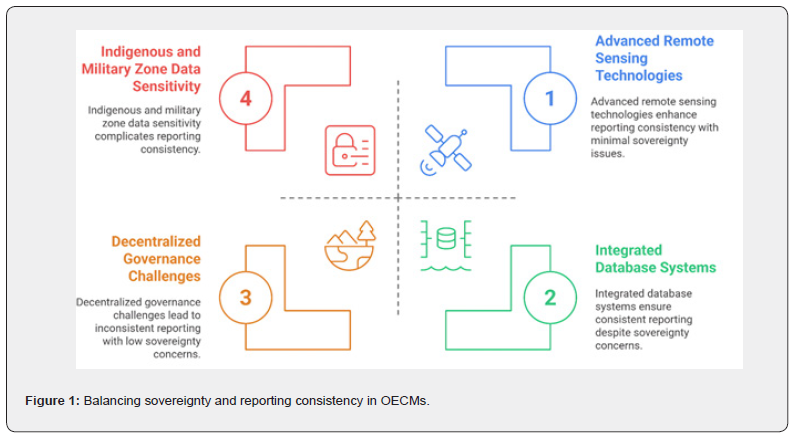

The effective implementation of OECMs offers a range of benefits that extend beyond biodiversity conservation, positioning them as critical tools for addressing broader socio-ecological challenges. As recognized under the IUCN Nature-based Solutions (NbS) Global Standard, OECMs contribute to multiple objectives, including climate resilience, sustainable resource management, and inclusive governance. These benefits are interconnected, ensuring that OECMs not only secure long-term ecological outcomes but also support local livelihoods, promote equitable decision-making, and enhance economic viability.

The IUCN NbS Global Standard provides a framework to

ensure that conservation interventions, including OECMs, are

effective, sustainable, and equitable. The standard consists of

eight criteria, which OECMs can help fulfil in the following ways

(Figure 2):

1. Effectively addressing societal challenges – OECMs

support climate resilience, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable

livelihoods by maintaining healthy ecosystems that provide

critical services such as water purification, food provisioning, and

coastal protection. For example, Thailand’s mangrove ecosystems,

recognized as OECMs, play a vital role in mitigating climate change

impacts and reducing disaster risks. Community-led restoration

projects in Krabi province have improved carbon sequestration

and provided storm protection. These initiatives align with

national climate adaptation strategies and demonstrate the socioeconomic

benefits of OECMs.

2. Designing for scale – OECMs contribute to conservation

at landscape and seascape levels by integrating diverse governance

models, including Indigenous and community-led initiatives. By

enhancing ecosystem connectivity, OECMs complement protected

areas in addressing large-scale conservation challenges such

as habitat fragmentation and species migration in response to

climate change.

3. Delivering biodiversity benefits – As areas governed and

managed to sustain long-term biodiversity outcomes, OECMs help

maintain ecological integrity. They support species conservation,

protect ecosystem functions, and provide refuge for climatesensitive

species, aligning with global biodiversity conservation

goals.

4. Economically viable – OECMs create economic

opportunities by promoting sustainable natural resource

management, ecotourism, and community-based conservation

enterprises. Their ability to attract investment through

mechanisms such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF) further

enhances their viability.

5. Balancing trade-offs – Effective OECMs incorporate

participatory decision-making that ensures fair trade-offs

between conservation and development needs. For example,

Japan prepared a “Potential Map of Ecosystem Conservation/

Restoration to Promote Eco-DRR” as an easy-to-use visual guide

to apply Eco-DRR for sustainable land use and management [59].

This map is expected to be used to plan and manage OECMs by

applying NbS concepts and approaches.

6. Managed adaptively based on evidence – OECMs

contribute to long-term conservation success through ongoing

monitoring, evaluation, and adaptive management, particularly in

response to climate change. Traditional ecological knowledge and

community-driven governance play a vital role in ensuring that

these areas continue to meet conservation and socio-economic

objectives.

7. Sustainably governed – OECMs recognize and support

diverse governance models, including Indigenous and local

community stewardship, private-sector conservation, and multistakeholder

partnerships. This diversity strengthens conservation

effectiveness and enhances the sustainability of governance

arrangements.

8. Ensuring equity and inclusivity – OECMs uphold the

rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities by securing

land tenure, respecting traditional knowledge, and ensuring fair

benefit-sharing. These principles reinforce the social legitimacy

and long-term success of OECMs as NbS.

‘Figure 3 highlights how OECMs contribute to the eight criteria of the IUCN NbS Global Standard, demonstrating their role in biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, governance, and equity. The assessment, based on a qualitative scoring (1- 10), shows that OECMs excel in biodiversity benefits, adaptive management, and inclusivity, while financial sustainability and scalability require further investment. This visualization underscores the importance of OECMs as effective, nature-based conservation tools that complement protected areas and support global environmental goals.

Furthermore, OECMs can serve as nature-based solutions supporting community resilience during crises [60]. By preserving ecosystem services like water purification and food provisioning, they offer direct benefits to local populations whose livelihoods may be disproportionately impacted during pandemics. OECMs can also be integrated into recovery plans by promoting sustainable development pathways that prioritize both environmental conservation and socio-economic stability [61].

Securing financing from global climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), can bolster OECM implementation and management [62,63]. Additionally, integrating OECMs into nature-based solution initiatives enhances their visibility and strengthens stakeholder engagement. Highlighting the socioeconomic benefits of OECMs, such as improved livelihoods and community resilience, can also generate broader support and investment [11].

Incorporating OECMs into national climate adaptation strategies also underscores their role in delivering ecosystem services, enhancing their relevance in broader environmental and policy frameworks [16,56]. This approach aligns with the growing recognition of nature-based solutions in addressing biodiversity loss and climate change [11,57].

Embedding OECMs in National Biodiversity Strategies

Incorporating OECMs into National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) ensures alignment with biodiversity targets and encourages stakeholder collaboration [9,64,65]. Aligning with National Action Plans and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) is equally important. Embedding OECMs within these strategies provides a structured framework for their recognition, monitoring, and reporting, linking them to global biodiversity objectives [33,66].

Strategic action plans should include clear indicators for measuring the effectiveness of OECMs, ensuring their contributions to biodiversity goals are quantifiable [67]. Furthermore, integrating OECMs into sectoral policies, such as agriculture, forestry, and urban planning, amplifies their conservation impact. This alignment ensures that OECMs are not only recognized but actively contribute to national and international commitments under frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [68].

Vietnam integrates OECMs into its National Biodiversity Strategy by recognizing locally managed fisheries and agroforestry systems. These measures contribute to biodiversity targets and Sustainable Development Goals. Clear indicators for measuring the effectiveness of these areas ensure their contributions are documented and aligned with global objectives [69].

Japan has developed its 30by30 Roadmap, outlining key actions to achieve Target 3 domestically. This includes the certification of conserved areas as OECMs, based on the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan of Japan 2023–2030. To facilitate the roadmap’s implementation, Japan launched the 30by30 Alliance for Biodiversity, a multi-stakeholder platform comprising businesses, local governments, and NGOs. Alliance members aim to strengthen area-based conservation efforts and showcase leading examples that contribute to the 30by30 target [59].

China updated its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) in 2024 for the period 2023–2030, aligning it with the KM-GBF. For the first time, OECMs have been formally recognized in national biodiversity policy, listed under Priority Action 9: In Situ Conservation of Biodiversity. The strategy prioritizes standardizing OECMs and conducting pilot demonstrations to enhance their implementation [29].

In ASEAN, efforts to advance OECMs are led by the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity (ACB). In 2019, ACB organized a regional workshop on Aichi Target 11 and OECMs, fostering collaboration in East and Southeast Asia on recognizing, reporting, and supporting OECMs. In 2021, ACB convened an Experts Meeting on OECMs and the Post-2020 GBF, focusing on regional challenges and opportunities. Beyond these meetings, OECMs are integrated into broader ASEAN initiatives, including the Regional Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (under development), the ASEAN Heritage Parks Regional Action Plan (2023–2030), and the ASEAN project on effectively managing ecological networks of marine protected areas in large ecosystems [13].

In Malaysia, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES) has incorporated OECMs and Target 3 in the recent review of its NBSAP [70]. Additionally, the Ministry is developing a National Framework for OECMs which is expected to be rolled out by late 2025.

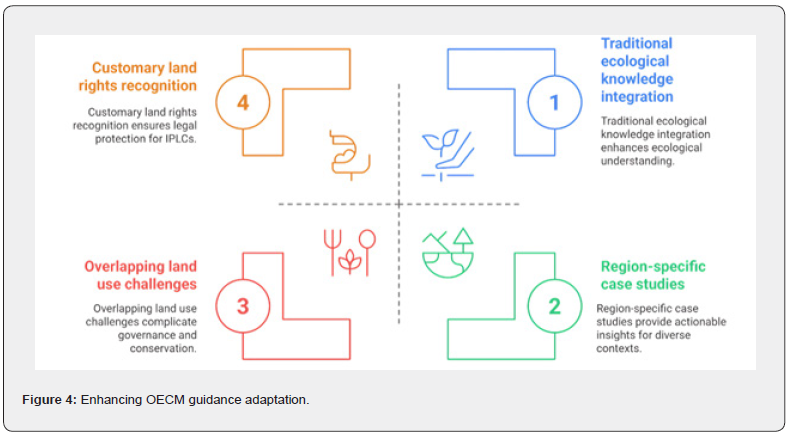

Adapting Global OECM Guidance

Adapting global OECM guidelines to national contexts requires a nuanced understanding of diverse governance structures and land tenure systems [1]. The current IUCN guidelines [10] touch on these aspects but lack essential strategies at the regional, national and local contexts, as well as for addressing the complexities inherent in decentralized governance models or traditional land use practices. For example, in regions where Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) manage land, ensuring legal recognition of customary land rights is critical. Similarly, integrating private land conservation efforts into OECM frameworks necessitates clear protocols for collaboration and monitoring. By incorporating case studies and best practices from countries that have successfully aligned OECM implementation with local governance and tenure systems, the guidance could provide more actionable insights and foster wider applicability. Developing tailored criteria and governance models ensures that OECMs are culturally relevant, ecologically viable, and locally acceptable [1,10]. However, the current IUCN guidance does not sufficiently address the specific challenges of tailoring these criteria to diverse cultural and ecological contexts. For instance, integrating traditional ecological knowledge with scientific methodologies often lacks clear procedural frameworks, leaving room for inconsistencies. Furthermore, the guidance underrepresents the complexity of managing OECMs in areas with overlapping land uses or contested governance. Addressing these gaps requires more comprehensive tools for stakeholder engagement, contextualizing ecological assessments, and aligning conservation goals with local values and socio-political realities. Providing region-specific case studies and practical applications would significantly enhance the usability and effectiveness of the guidance.

Incorporating traditional ecological knowledge from IP&LCs enhances the effectiveness of OECMs, particularly in culturally sensitive landscapes. Collaborative frameworks that integrate scientific and traditional knowledge foster innovation and inclusivity in conservation strategies [41,71,72]. For instance, the ICCA Consortium has successfully demonstrated how Indigenous Peoples’ Conserved Territories and Areas effectively blend traditional ecological knowledge with scientific methods to achieve long-term conservation outcomes. In Nepal, the Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) illustrate a model where local communities actively manage forest resources while receiving technical support from conservation agencies. Despite these successes, gaps remain in the IUCN guidance for systematically implementing such frameworks. Specifically, there is a lack of detailed methodologies for facilitating knowledge exchange and addressing power imbalances between scientific and traditional stakeholders. Developing protocols that emphasize co-creation of knowledge and equitable governance can bridge these gaps, ensuring more robust and inclusive conservation strategies. Efforts should also focus on building technical and institutional capacities to adapt and implement global guidelines effectively at local levels. Specifically, technical capacities should include training in GIS for participatory mapping and monitoring, as well as skills in biodiversity assessment methodologies to ensure accurate data collection and analysis. Institutional capacities should focus on establishing frameworks for participatory governance, enhancing collaboration between stakeholders, and creating mechanisms for long-term funding and resource allocation. Development of these capacities can be facilitated through targeted training programs, knowledge exchange workshops, and partnerships with international conservation organizations that provide technical expertise and funding support. Additionally, fostering local expertise by engaging universities and research institutions can help build a sustainable pipeline of skilled professionals dedicated to OECM management.

Figure 4 provides a visual illustration of the elements that allow to enhance OECM guidance adaptation for specific contexts.

In Japan, various types of OECMs have been recognized, including satoyama and satoumi (socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes), urban green spaces, shrine forests, and more. The classification of these areas is flexible, provided they meet the criteria outlined in Japan’s national OECM recognition scheme [13].

At the national level, it is important to adopt an appropriate and accessible name for OECMs to enhance public understanding and engagement. For instance, the Republic of Korea introduced the term ‘Nature Coexistence Areas’ (자연공존지역 / Jayeon Gongzone Jiyeok in Korean) as a more relatable designation for OECMs [73]. This name was selected based on expert consultations and a public survey, aligning with the Convention on Biological Diversity’s 2050 vision of “Living in Harmony with Nature” and the core principles of OECMs [30].

Japan’s satoyama landscapes serve as a strong example of how global OECM guidance can be successfully adapted to local contexts. These traditional socio-ecological landscapes and seascapes integrate biodiversity conservation with sustainable human livelihoods. The application of tailored criteria that incorporate cultural heritage and traditional ecological knowledge has strengthened their management and recognition under OECM frameworks [74].

Currently, the IUCN China Office is working in close collaboration with the Chinese OECM expert group to adapt the OECM standards. Once the customized OECM standards, criteria, toolkit, and guidelines are in place, the identification and evaluation of potential OECMs in China will become more accurate and efficient [75-77].

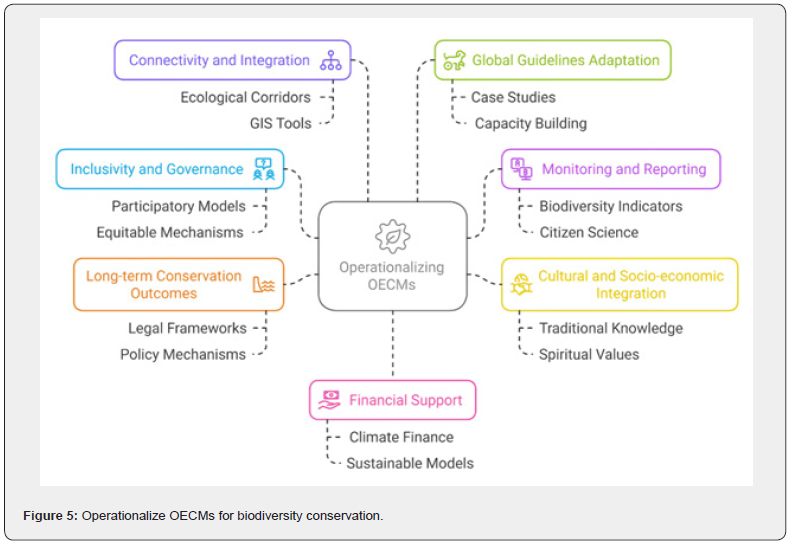

Recommendations: Solutions and Pathways

To address the identified challenges and gaps in the

implementation of OECMs, the following solutions and pathways

are recommended (Figure 5):

1. Enhancing inclusivity and equitable governance:

Strengthen participatory governance models that actively involve

landowners, other key stakeholders, and rights holders such as

Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs), the private

sector, and women and youth in the entire range of decisionmaking

processes. Establishing clear mechanisms to ensure

equitable participation and addressing power imbalances will

help foster inclusivity. For example, co-management agreements

that formally recognize customary land rights can empower IPLCs

to contribute effectively to OECMs management.

2. Developing adaptive monitoring and reporting

frameworks: Implement robust monitoring systems that

integrate both biodiversity and socio-economic indicators.

Fostering citizen science, utilizing advanced technologies, such

as remote sensing and AI-driven data analysis, can enhance realtime,

efficient and sustainable monitoring. Additionally, creating

region/national-specific reporting guidelines aligned with CBD

cycles will improve consistency and comparability of OECMs data.

3. Integrating cultural and socio-economic values:

Expand the guidance to include detailed methodologies for

incorporating cultural, spiritual, and socio-economic values into

conservation strategies. Practical tools for integrating traditional,

Indigenous and local ecological knowledge and scientific methods

should be developed, with specific examples of successful

applications.

4. Securing long-term conservation outcomes:

Establish legal and institutional frameworks to ensure the

longevity of OECMs. Policy mechanisms, such as conservation

easements, tax incentives, and land-use zoning as well as formal

certification schemes, can provide stability and protect OECMs

from future land-use changes or policy shifts. Building adaptive

capacities and enabling appropriate conditions within relevant

institutions will further enhance resilience to socio-economic

and environmental pressures. Moreover, a holistic conservation

approach that integrates both protected areas and OECMs is

necessary. Promoting and revitalizing a culture of coexistence

with nature—deeply rooted in the traditions of the Asia Region—

will be key to sustaining conservation efforts over the long term

5. Promoting connectivity and integration: Integrate

OECMs into larger conservation networks to strengthen

ecological connectivity and landscape-scale conservation efforts,

including the application of comprehensive planning systems

such as NBSAPs and national land use plans. Detailed strategies

for linking OECMs with existing protected areas, corridors, and

seascapes should be prioritized. Tools like Geographic Information

Systems (GIS) can play a critical role in visualizing and optimizing

connectivity.

6. Adapting global guidelines to local contexts: Tailor

global guidance to reflect diverse governance structures and

ecological realities according to the regional, national and local

context. Providing actionable case studies and templates that

align with local socio-political dynamics will ensure the guidance

is practical and implementable. Capacity-building initiatives

should be designed to equip stakeholders with the skills needed

to adapt guidelines effectively.

7. Securing financial support: Mobilize funding from

global climate and biodiversity finance mechanisms, such as the

Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Global Environment Facility

(GEF). Demonstrating the co-benefits of OECMs, such as their role

in climate adaptation and community resilience, will help attract

investment from a wider set of donors. Establishing sustainable

financing models at the local, national and regional levels,

including ecotourism and payment for ecosystem services, can

further support the long-term management of OECMs.

By implementing these solutions, OECMs can be operationalized more effectively, addressing current limitations while maximizing their potential to achieve global biodiversity targets.

Conclusion

The operationalization of OECMs presents both challenges and opportunities, particularly within the Asian context, where diverse socio-ecological landscapes, varying levels of economic development, intensive land use, and deeply ingrained cultural traditions shape conservation strategies. Addressing these complexities requires a nuanced approach that integrates governance, reporting, and spatial planning mechanisms tailored to local realities.

The current IUCN guidelines provide a robust foundation for advancing OECMs but fall short in offering detailed methodologies for ensuring inclusivity and adaptability. In some regions of Asia,where Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) manage vast and ecologically significant territories, equitable participation is paramount. Similarly, engagement of the private sector, other landowner, and applying landscape approach is also important. The participation of women, youth and other stakeholders is equally critical. Frameworks such as Nepal’s Community Forest User Groups demonstrate how participatory governance models can empower a wide range of stakeholders, ensuring conservation measures align with cultural and social priorities.

Adaptability is another critical dimension. Rapid urbanization and habitat fragmentation in regions like Southeast Asia require integrating OECMs into spatial planning frameworks. Technological innovations can help map ecological networks and support the creation of biodiversity corridors, strengthening ecological resilience and connectivity. Complementing these tools with real-time monitoring technologies enhances adaptive management, enabling timely responses to socio-economic and environmental changes.

Embedding OECMs in national biodiversity strategies, as seen in Vietnam’s integration of locally managed fisheries into its NBSAP, provides a pathway for aligning local initiatives with global biodiversity targets. Governance structures must reflect the diversity of stakeholders, with mechanisms to ensure equity and inclusiveness. This includes fostering trust through legal recognition of land rights, co-management agreements, and sustained capacity-building efforts.

In Japan’s satoyama landscapes, the blending of traditional ecological knowledge with conservation science illustrates the potential of adapting global OECM guidelines to local contexts. This approach underscores the need for tailored criteria that honour cultural heritage while achieving ecological goals. Such adaptations not only make OECMs more relevant but also strengthen their legitimacy among stakeholders.

OECMs also play a crucial role in addressing climate challenges. By serving as nature-based solutions, they enhance resilience to climate change and mitigate disaster risks through ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration and flood control. Policymakers must prioritize integrating OECMs into national climate adaptation strategies and mobilizeng resources from global climate funds, ensuring the long-term sustainability of these measures.

Ultimately, the success of OECMs hinges on coordinated, inclusive, and adaptive approaches. A focus on integrating ecological science, traditional knowledge, and innovative governance will ensure OECMs evolve as transformative tools for biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and sustainable development. The insights and recommendations presented in this paper offer actionable pathways for addressing current limitations, emphasizing the importance of long-term commitment and localized strategies to achieve global conservation goals particularly in the Asian context.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

MKSP, OC: Writing – original draft, review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration; DC, SS, SMS, HM, MD, YS, WS, HH, EI, NC, SC, VBM, SH, JS, SP, AH, YK, SP, SKH: Writing – review & editing.

References

- Dudley N, Jonas H, Nelson F, Parrish J, Pyhälä A, et al. (2018) The essential role of other effective area-based conservation measures in achieving big bold conservation targets. Global Ecology and Conservation 15: e00424.

- Jonas HD, Barbuto V, Jonas HC, Kothari A, Nelson F (2014) New steps of change: Looking beyond protected areas to consider other effective area-based conservation measures. Parks 20(2): 111-128.

- CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity) (2018) Decision 14/8: Protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. CBD/COP/DEC/14/8.

- Jonas HD, Bingham HC, Bennett NJ, Woodley S, Zlatanova R, et al. (2024) Global status and emerging contribution of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) towards the '30x30' biodiversity Target 3. Frontiers in Conservation Science 5: 1447434.

- Jonas HD, MacKinnon K, Dudley N, Hockings M, Jessen S, et al. (2018) Other effective area-based conservation measures: from a biodiversity-focused to a people-centered approach. Parks 24(2): 57-68.

- Corrigan C, Bingham H, Devillers R, McOwen CJ, Kingston N, et al. (2018) Quantifying the contribution of OECMs to Aichi Target 11 and beyond. Conservation Biology 32(4): 948-956.

- Bingham H, MacKinnon K, Jonas H (2019) The role of OECMs in achieving Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 and supporting SDGs. Sustainability Science 14(2): 755-767.

- Lemieux CJ, Gray PA, Devillers R, Edge G (2021) Understanding the role of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) in achieving connectivity conservation. Landscape and Urban Planning 211: 104129.

- Schleicher J, Peres CA, Devillers R (2021) Aligning OECMs and protected areas in national biodiversity strategies. Biological Conservation 260: 109181.

- IUCN WCPA (World Commission on Protected Areas) (2019) Recognising and reporting other effective area-based conservation measures. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) (2020) Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions. A user-friendly framework for the verification, design and scaling up of NbS. First edition. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Hilty J, Worboys GL, Keeley A, Woodley S, Lausche BJ, et al. (2020). Guidelines for conserving connectivity through ecological networks and corridors. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- IUCN Asia Regional Office (2024) APAP roadmap for OECMs: APAP Regional OECM Consultation Workshop, 8–9 July 2024. IUCN Asia Regional Office.

- Worboys GL, Ament R, Day JC, Lausche B, Locke H, et al. (2020) Connectivity Conservation Management: A Global Guide. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- Gross JE, Woodley S, Welling LA, Watson JE (2016) Adapting to climate change: Guidance for protected area managers and planners. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- Watson JE, Dudley N, Segan DB, Hockings M (2020) Set a global target for ecosystems. Nature 578(7795): 360-362.

- Ahmadia GN, Glew L, Eggleston DB, Friedlander AM (2020) Incorporating OECMs into marine spatial planning. Marine Ecology Progress Series 654: 219-234.

- Maxwell SL, Cazalis V, Dudley N, Hoffmann M, Rodrigues ASL, et al. (2020) Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature 586: 217-227.

- Gurney GG, Pressey RL, Ban NC, Álvarez‐Romero JG, Jupiter S, et al. (2015) Efficient and equitable design of marine protected areas in Fiji through inclusion of stakeholder‐specific objectives in conservation planning. Conservation Biology 29(5): 1378-1389.

- Paterson A (2023) Scoping the potential influence of law on terrestrially located other effective area-based conservation measures. Law, Environment and Development Journal 18(1): 32-50.

- Saura S, Bastin L, Battistella L, Mandrici A, Dubois G (2018) Protected area connectivity: Shortfalls in global targets and country-level priorities. Biological Conservation 219: 53-67.

- Chazdon RL, Brancalion PH, Lamb D, Laestadius L, Calmon M, et al. (2020). A policy‐driven knowledge agenda for global forest and landscape restoration. Conservation Letters 10(1): 125-132.

- Alves-Pinto H, Geldmann J, Jonas H, Maioli V, Balmford A, et al. (2021) Opportunities and challenges of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) for biodiversity conservation. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 19(2): 71-78.

- Lewis E, Day JC, Fitzsimons J, Jonas HD (2020) Defining governance for other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) in marine and coastal areas. Marine Policy 119: 104064.

- Laffoley D, Dudley N, Jonas H, MacKinnon K, MacKinnon D, et al. (2017) An introduction to “other effective area-based conservation measures” under Aichi Target 11 of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Origin, interpretation and emerging ocean issues. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 27(S1): 130-137.

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) (2020) Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions. A user-friendly framework for the verification, design and scaling up of NbS. First edition. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Mondal SH, Debnath P (2017) Spatial and temporal changes of Sundarbans Reserve Forest in Bangladesh. Environment and Natural Resources Journal 15(1): 51-61.

- Getzner M, Islam MS (2013) Natural resources, livelihoods, and reserve management: A case study from Sundarbans mangrove forests, Bangladesh. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 8(1): 75-87.

- Zhang Y, Zhang L, Sun Y, Li D, Wang W, et al. (2024) A stocktaking report on other effective area-based conservation measures in China. IUCN, Beijing, China.

- Heo HY, Park SJ (2023) A Study on Identifying OECMs in Korea for Achieving the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework Target 3. Korean Journal of Environmental Ecology 37(4): 302-314.

- International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) (2025) Leveraging the prospects and potential of OECMs for transboundary cooperation in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. Workshop Proceedings. Kathmandu, Nepal: ICIMOD.

- Donald PF, Buchanan GM, Balmford A, Bingham H, Couturier AR, et al. (2019) The prevalence, characteristics and effectiveness of Aichi Target 11’s "other effective area-based conservation measures" (OECMs) in Key Biodiversity Areas. Conservation Letters 12(5): e12659.

- Jonas HD, MacKinnon K, Dudley N, Hockings M, Jessen S, et al. (2018) Other effective area-based conservation measures: From Aichi Target 11 to the post-2020 biodiversity framework. Parks 24(2): 49-62.

- UNEP-WCMC & IUCN (2021) Protected Planet Report 2020. UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, Cambridge, UK and Gland, Switzerland.

- Kohsaka R (2023) Biodiversity, COP15, and OECMs. The Japanese Forest Society Congress 134: 27.

- Visconti P, Butchart SH, Brooks TM, Langhammer PF, Marnewick D, et al. (2019) Protected area targets post-2020. Science 364(6437): 239-241.

- Gannon P, Dubois G, Dudley N, Ervin J, Ferrier S, et al. (2022) Monitoring OECMs: Approaches and challenges. Conservation Science and Practice 4(5): e1265.

- Borrini-Feyerabend G, Dudley N, Jaeger T, Lassen B, Pathak Broome N, et al. (2013) Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- Artelle KA, Zurba M, Bhattacharyya J, Chan DE, Brown K, et al. (2019) Supporting resurgent Indigenous-led governance: A nascent mechanism for just and effective conservation. Biological Conservation 240: 108284.

- Jonas HD, Ahmadia GN, Bingham HC, Briggs J, Butchart SHM, et al. (2021) Equitable and effective area-based conservation: Towards the conserved areas paradigm. Parks 27(1): 71-84.

- Corrigan C, Bingham H, Shi Y, Lewis E, Chauvenet A, et al. (2021). The role of private and community land in achieving biodiversity goals. Nature Sustainability 4: 528-534.

- Garnett ST, Burgess ND, Fa JE, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Molnár Z, et al. (2018) A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability 1(7): 369-374.

- Reed MS (2008) Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation 141(10): 2417-2431.

- Oldekop JA, Holmes G, Harris WE, Evans KL (2016) A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conservation Biology 30(1): 133-141.

- Zurba M, Beazley KF, English E, Buchmann-Duck J (2019) Indigenous protected and conserved areas (IPCAs), Aichi Target 11 and Canada's Pathway to Target 1: Focusing conservation on reconciliation. Land 8(1): 10.

- Heo HY (2024) Cranes over Cheorwon, cultivating conservation and community: Results from the Nature Coexistence between farmers and cranes. PANORAMA.

- Pokharel RK, Suvedi M (2007) Indicators for measuring the success of Nepal's community forestry program: A local perspective. Human Ecology Review 14(1): 68-75.

- Bennett NJ, Roth R, Klain SC, Chan K, Clark DA, et al. (2017) Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conservation Biology 31(1): 56-66.

- Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J (2005) Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30: 441-473.

- Armitage DR, Plummer R, Berkes F, Arthur RI, Charles AT, et al. (2009) Adaptive co‐management for social-ecological complexity. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7(2): 95-102.

- Jonas HD, Lee E, Jonas HC, Matallana-Tobon C, Wright KS, et al. (2017) Will 'other effective area-based conservation measures' increase recognition and support for ICCAs? Parks 23(2): 63-78.

- Woodley S, Locke H, Laffoley D, MacKinnon K, Sandwith T, et al. (2019) A review of evidence for area‐based conservation targets for the post‐2020 global biodiversity framework. Parks 25(2): 31-46.

- Park J-e (2019) The legal protection of the intangible cultural heritage in the Republic of Korea. In: PL Petrillo (Ed.), The legal protection of the intangible cultural heritage: A comparative perspective. Springer, pp. 69-83.

- Griscom BW, Adams J, Ellis PW, Houghton RA, Lomax G, et al. (2017) Natural climate solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(44): 11645-11650.

- Cohen-Shacham E, Andrade A, Dalton J, Dudley N, Jones M, et al. (2019) Core principles for successfully implementing and upscaling Nature-based Solutions. Environmental Science & Policy 98: 20-29.

- Díaz S, Settele J, Brondízio ES, Ngo HT, Agard J, et al. (2019) Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science 366(6471): eaax3100.

- Nesshöver C, Assmuth T, Irvine KN, Rusch GM, Waylen KA, et al. (2017) The science, policy and practice of nature-based solutions: An interdisciplinary perspective. Science of the Total Environment 579: 1215-1227.

- Deutz A, Heal GM, Niu R, Swanson E, Townshend T, et al. (2020) Financing nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap. The Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy, and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

- Ministry of the Environment of Japan (2023) A guide to Eco-DRR practices for sustainable community development (summary version): Using potential map of ecosystem conservation/restoration to promote Eco-DRR.

- Hockings M, Dudley N, Elliott W, Napolitano Ferreira M, MacKinnon K, et al. (2020) COVID-19 and protected and conserved areas. Parks 26(1): 7-24.

- Golden Kroner R, Barbier EB, Chassot O, Chaudhary S, Cordova L, et al. (2021) COVID-era policies and economic recovery plans: Are governments building back better for protected and conserved areas? Parks 27(Special Issue): 135-148.

- Seddon N, Chausson A, Berry P, Girardin CA, Smith A, et al. (2020) Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 375(1794): 20190120.

- Chausson A, Turner B, Seddon D, Chabaneix N, Girardin CAJ, et al. (2020) Mapping the effectiveness of nature‐based solutions for climate change adaptation. Global Change Biology 26(11): 6134-6155.

- CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity) (2020) Update of the zero draft of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. CBD/POST2020/PREP/2/1.

- Whitehorn PR, Navarro LM, Schröter M, Fernandez M, Rotllan-Puig X, et al. (2019). Mainstreaming biodiversity: A review of national strategies. Biological Conservation 235: 157-163.

- Xu X, Tan Y, Chen S, Yang G (2021) Changing patterns and determinants of natural capital in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China: A new perspective from the ecosystem services connection. Science of The Total Environment 466-467: 326-337.

- Bastin L, Buchanan GM, Jonas H (2020) Mapping and evaluating other effective area-based conservation measures in the post-2020 framework. Nature Sustainability 3(8): 669-677.

- Diz D, Johnson D, Riddell M, Rees S, Battle J (2018) Mainstreaming marine biodiversity into the SDGs: The role of other effective area-based conservation measures (SDG 14.5). Marine Policy 93: 251-261.

- IUCN (2024) Viet Nam National Workshop on OECMs Ha Noi, Viet Nam, 15 February 2024.

- NRES (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability, Malaysia) (2023) National Policy on Biological Diversity, 2022 – 2030. NRES, Putrajaya, Malaysia.

- Berkes F (2009) Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management 90(5): 1692-1702.

- Chassot O, Valverde-Blanco A, González-Maya JF, Chaudhary S, Monge-Arias G (2022) Thinking about regeneration: A global vision for integral protected and conserved areas management. Regeneration 1(1): 18-33.

- Government of Republic of Korea. 2023. The 5th National Biodiversity Strategy (2024-2028).

- Ichikawa K, Toth GG (2012) The Satoyama landscape of Japan: The future of an indigenous agricultural system in an industrialized society. In: P Nair, D Garrity (Eds.), Agroforestry - The future of global land use (Advances in Agroforestry, Vol. 9). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Butchart SHM, Clarke M, Smith RJ, Sykes RE, Scharlemann JPW, et al. (2015) Shortfalls and solutions for meeting national and global conservation area targets. Conservation Letters 8(5): 329-337.

- CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity) (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. CBD/COP/15/L.25.

- Ministry of the Environment of Japan (2022) Japan establishes a 30by30 roadmap and launches the 30by30 alliance for biodiversity.