Abstract

This study examined bird species diversity, richness and evenness across multiple habitats within Msolwa area, Nyerere National Park. The area comprised of six major habitat categories, forest, woodland, wooded grassland, grassland, bushland and river line, which were defined basing on the visible attribute (height, lifeform and species composition) and ecological features of the habitat. Three line transects each with a length of 4km were established in every surveyed habitat. Sixteen point counts, each with 100-meter radius were established along a single transect at 250m intervals. All bird species seen and heard within the 100m diameter were observed and recorded. In total, 3,219 individuals of birds, comprising 266 species belonging to 21 orders and 67 families were recorded over the six distinct habitats. Woodland habitat had the highest individual number of birds 1993 with highest species richness 36.56. Forest habitat showed the least 16 number of individual birds with lowest species richness 1.44. The Shannon-Winner Index of diversity H’, was used to calculate diversity of bird species, where highest diversity of bird species was observed in woodland H’=4.883 followed by Grassland H’=3.924 and the least was forest habitat with H’=1.515. The diversity of bird species varied significantly due to variations in adaptation ability of different bird species in the surveyed habitat. This study highlights gaps in our knowledge on diversity of bird species across multiple habitats and suggests that habitat transition and connectivity is a more important determinant of avian species richness and community structure.

Keywords: Bird diversity; Habitats; Resource availability; Species richness

Background Information

Protected Areas (Pas) are areas set aside by the government for the preservation of natural ecosystems to protect endangered species and provide opportunities for recreation [1]. They contribute to the local community’s livelihood improvement in terms of employment opportunities and social services provision [2]. Additionally, PAs generate governmental revenue through nature-based tourism activities [3]. Beyond their economic contributions, PAs play a significant role in conserving biodiversity, and provide habitats for numerous species including mammals, Microbes, plants, avian and insects each of which fulfill an ecological role essential for ecosystem balance and co-existence [4].

In Namibia, about 13.8% of the country’s land area is retained as Protected Areas for conservation of biodiversity, however, conservation management policies remained focused on active manipulation of the size and movement of mammal population [5]. This is due to significant contribution PAs offers in conserving wild animals and more the endemic species [5]. In South Africa, Conservation activities have been promoted for quit a long period with Kruger National Park being the major key area for conservation. The park is home to 14% of the country’s terrestrial bird species, residing over an array of habitats [6]. The presence of multiple habitats promotes a high diversity of bird species over the park. However, illegal human activities (collection of fuel, grazing) and habitat fragmentation has been affecting negatively the diversity and distribution of bird species at Kruger National Park [6].

Tanzania is rich in biodiversity and is home of ionic species including lions, cheetah, black rhinoceros, elephants as well as bird species just to mention a few of them. Approximately 44% of Tanzania land is allocated for protection with varying conservation statuses including National Parks, Game Reserves, Marine Parks, Forest Reserves, Wildlife Management Areas and Conservation Areas [7]. They serve as valuable areas for research activities in ecology, evolution and conservation activities. Different habitats of various vegetation cover within the area, are essential for daily requirements of wild animals, however habitat loss and poaching activities threatens their life, leading to decline in their number [8].

Nyerere National Park located in Eastern part of Tanzania, which of recently upgraded from Game Reserve in the year 2019, provides a broad array of habitats that offer unique ecological conditions to support diverse wild populations. Among these, the avian group stands out occupying a diverse of habitats that provides shelter for canopy-dwelling species, while grasslands and wetlands attract ground-nesting birds and waterfowls, [9] respectively. While numerous studies have explored the role of single habitat types in avian diversity, few have explored multiple habitats within the same ecosystem. For example, in their studies Rajpar [10] and Li et al. [11], assessed Riverine Forest as a significant habitat harboring a wide range of bird species. These studies suggest that further research is necessary to investigate the core determinants of avian diversity within the ecosystems. Another study by Basile, (2021) assessed the abundance, species richness and diversity of forest bird assemblages. This study suggests that a simple singular habitat structure cannot represent viable species composition of the whole ecosystem, hence the need to investigate richness, abundance and diversity of bird species across multiple habitats in the same ecosystem. This will adversely allow researchers to assess the ecological preferences of bird species and identify key habitats that are vital for their conservation. The approach, furthermore, helps to inform park management strategies aimed at preserving avian biodiversity.

This study therefore bridged the knowledge gap by analyzing how bird species diversity, richness and composition vary across different habitat types in Nyerere National Park specifically at Msolwa area. The study predicted that there is equal distribution of bird species diversity across the surveyed habitats. Firstly, the study aimed at exploring species diversity, richness and evenness of various habitats in the same ecosystem. Secondly, to explore which habitat type and composition predict a high bird diversity. The results ultimately provide insights into habitat specific conservation needs. Furthermore, by analyzing these differences, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of habitats’ importance in avian conservation and park management.

Material and Method

Description of the study area

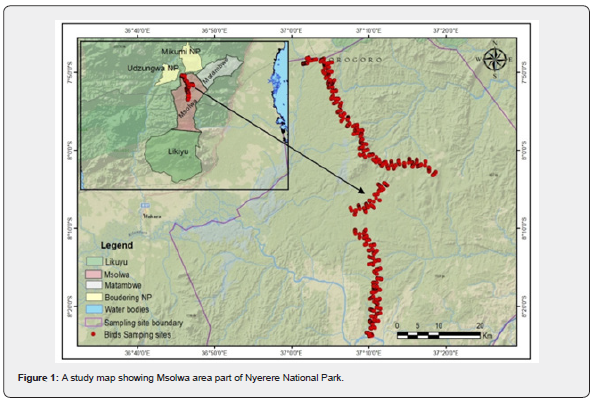

This survey was conducted in the Msolwa area part of Nyerere National Park (NNP), which of recently was upgraded from Selous Game Reserve. It is the largest Park in Africa located between 7.75° and 10.5° southern and 36.0° and 38.7° Eastern Zone of Tanzania covering an area of over 30,000 square kilometers with relative undisturbed ecological and biological disturbances (Figure 1). Msolwa area exhibit 100-400m altitude with soil texture varying from sandy to different loams which supports the growth of miombo woodland, and Combretum thickets [12]. Msolwa area transverses different habitats mainly forest, woodland, shrubland, grassland, water bodies, and other land cover including bare land and burnt area. Additionally, the area has bimodal rainfall season and the short rainfall in November and December ranging between 750 and 1300 millimeters. The Park is home of several wild animals including Savanna Elephants (Loxodonta Africana), African Cape Buffalo (Syncerus caffer), Lion (Panthera leo) and African Wild dogs (Lycaon pictus), however few studies documents on the bird species [13].

Data collection

Three transects of four-kilometer length were established in each surveyed habitat within Msolwa area part of Nyerere National Park. The study area comprised of six major habitat categories, Forest, woodland, wooded grassland, Grassland, bushland and river line habitats, which were defined basing on the visible attribute (height, lifeform and species composition) and ecological features of the habitat [14]. Each transect line produced sixteen-point count at an interval of 250 meters to minimize the risk of double count making a total of 48 point counts per surveyed habitat.

To every introduced point-count, all birds seen and heard within 100m-diameter were identified and recorded in 10min duration following previous study [15]. Limiting counts to a 100m-diameter helps to reduce the differences in detectability of birds among habitat types due to vegetation structure and minimizes biases and errors in species identification and distance estimate [16]. Observations were carried out during early morning (0700-0900 hours) and late afternoon (1600-1800hours) when birds were active with the aid of field guidebook and binocular [17]. Several parameters were recorded in a standardized sheet including GPS Coordinates, time, habitat type, date, individual bird species and their actual number.

Data analysis

The IUCN Red List was used to determine conservation status of detected bird species [18]. Data was cleaned using Microsoft Excel software. Shannon-Winner Index of diversity H’, was used to calculate the diversity of species across the surveyed habitats as well as diversity values by using PAST (Version 4.03). Abundance of species in the three habitats was assessed as the total number of birds recorded on a particular site (Total count per site). Distribution of species in the study sites was recorded as presence or absence of each species, determined by evenness. Relative abundance of species in the study sites was computed as number of respective species per total number of species in the respective habitat, i.e., the proportional of individual species relative to the total number of species in a site. One-way ANOVA was used to determine if there is significant difference between at least two habitats in terms of diversity, while Turkey post-Hoc test finalized which specific pairs of habitats differ. We used (P<0.5) for measuring statistical significance value.

Results

Species composition

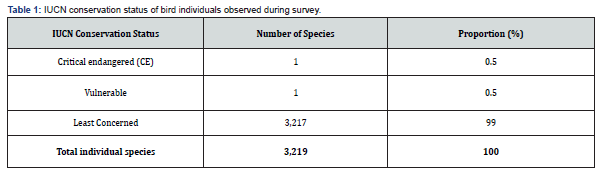

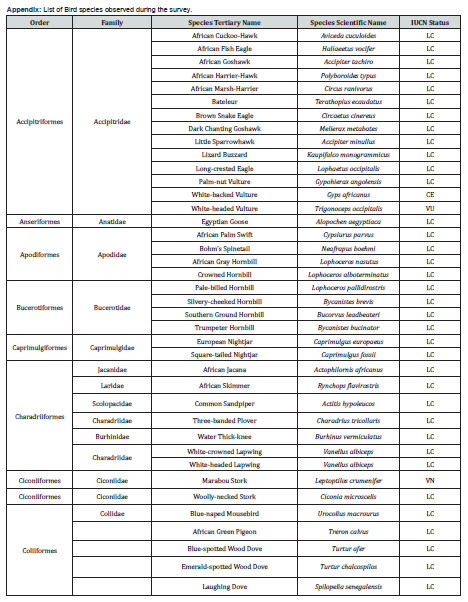

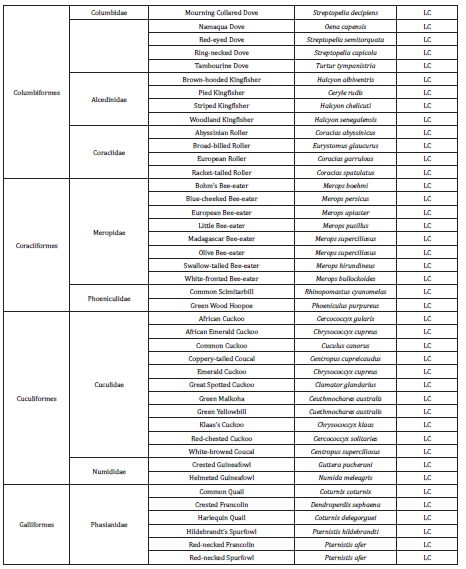

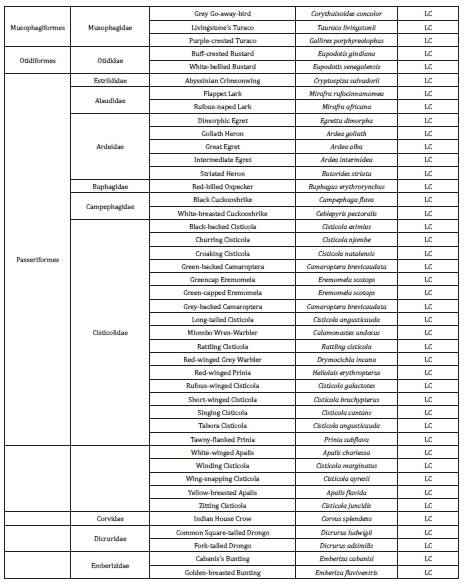

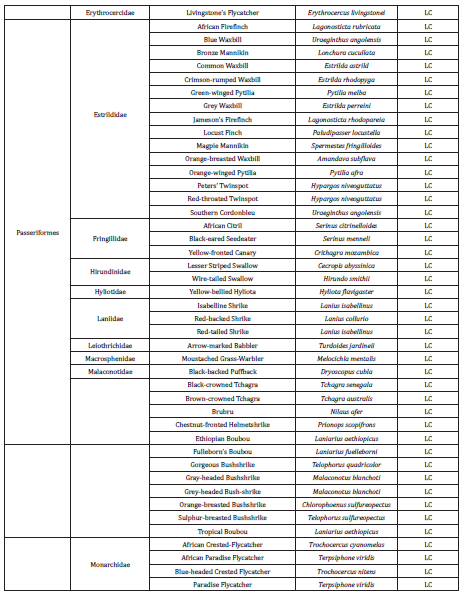

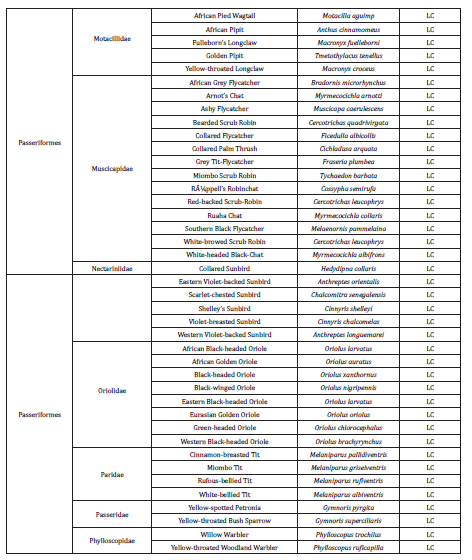

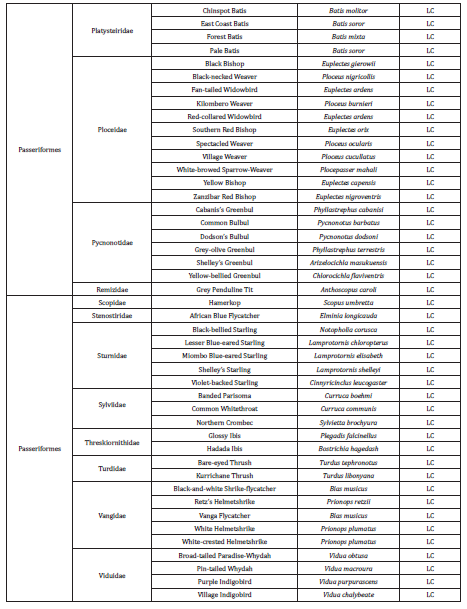

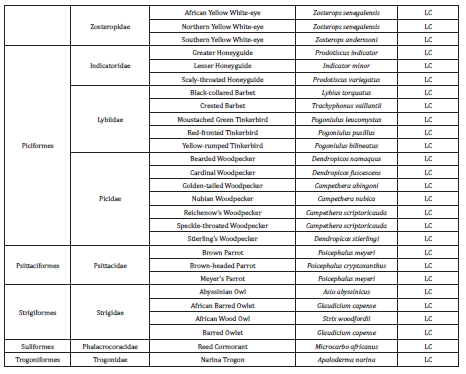

A total of 3,219 individual birds comprising of 266 species, belonging to 21 orders and 67 families, were recorded across the six major habitats. The dominant family in the study area was Cisticolidae, constituting 13% of the total species followed by Bucerotidae (7%), Estrildidae (5%) and Accipitridae (5%). Order Passeriformes constituted 68% of all the species observed, with the highest number of observations across the six habitats, followed by Coraciiformes and the least was Trogoniformes with 0.13% of all species observed. A series of species categorized in different IUCN status were recorded including one individual specie White-backed Vulture (Gyps africanus) categorized as a Critical Endangered species in the study area, Marabou Stork (Leptoptilos crumenifer) as Vulnerable and the rest are categorized as Least Concerned by International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Table 1).

Species relative abundance and distribution

The most abundant species in riverine habitat was Zanzibar Red Bishop (Euplectes nigroventris) with the highest Index of Relative Abundance (IRA) of 16.57%. Black-bellied starling (Notopholia corusca) was the most abundant specie in grassland and bushland habitats with IRA of 24.67%, where else in woodland and forest habitat, Rattling Cisticola (Cisticola Chiniana) was the most abundant specie with IRA of 5.17%. Twenty-one (21) species had the lowest IRA of 0.27% each across the surveyed habitats.

Species diversity and richness

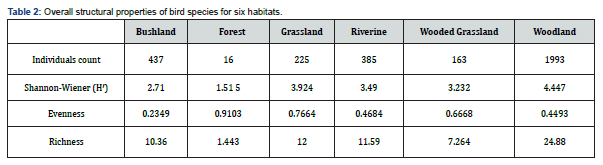

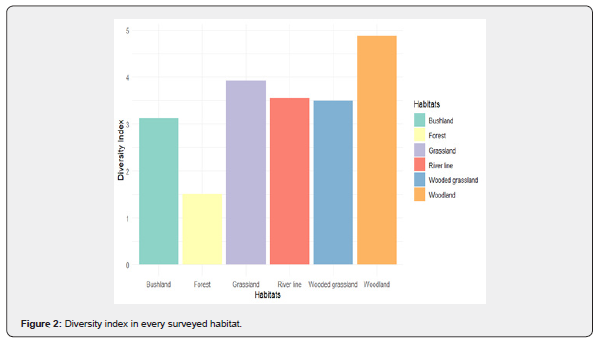

The overall species richness of birds was highest in woodland habitat (24.88), followed by grassland (12), riverine (11.59), bushland (10.36), wooded grassland (7.264) and the lowest species richness was observed in forest habitat (1.443) (Table 2). Species diversity varied significantly across the selected habitats (P < 0.005). Woodland and Grassland habitats hosted highest diversity of avian group (H’= 4.447), (H’=3.924) respectfully followed by Riverine (H’=3.49), wooded grassland habitats (H’=3.232), Bushland habitat (H’=2.71) and the lowest species diversity was observed in forest habitat (H’=1.515) as illustrated under (Figure 2). Bird species were evenly distributed across the surveyed habitats with the exception of forest habitat (Table 2). Diversity of bird species varied significantly between various habitats, Forest habitat varied significantly with bushland habitat P<0.05, Riverine habitat varied significantly with Grassland habitat P<0.05, wooded grassland habitat varied significantly with grassland habitat and lastly was woodland habitat which varied significantly with grassland habitat (P<0.05).

Discussion

Species composition

The study recorded a total of 3,219 individual birds comprising of 266 species, belonging to 21 orders and 67 families. The common specie was Black bellied starling (Notopholia corusca) which was observed in every surveyed habitat, while White-backed Vulture (Gyps africanus) and Marabou Stork (Leptoptilos crumenifer) were rarely found in the study site. The dominant family in the study area was Cisticolidae constituting 13% of the total species. The family had highest number of bird species due to composition of a wider range of bird species feeding on variety of guilds [19].

Species diversity and richness

Diversity of the recorded bird species varied significantly across the surveyed habitats due to variation in vegetation structure. This corresponds to the findings of Okosodo et al. [20] whose results suggested that variation in vegetation composition brings about differences in food availability, which attracts a diverse of bird species resulting in different bird species composition. Diversification of food materials at woodland habitats enhance a number of bird species which then affected positively diversity of bird species [21]. Mature trees are valuable food sources for diverse bird species in protected areas [19]. Their presence attracts several bird species, which then initiates high species richness. The presence of shelter in woodland habitat attracts canopy-dwelling species, which ultimately affect positively bird species richness [22].

Woodland habitats have also demonstrated high species richness and diversity in past studies [21] Basile (2021), suggest that increase of broadleaf in the existing Woodland habitats usually boost the abundance, richness and diversity of bird species. These broadleaves decrease isolation level within bird species, thus enhance structural connectivity and finally favoring majority of species. Furthermore, the habitat is an important home for one among the most critical endangered species in the world, White-backed Vulture (Gyps africanus). The species prefer woodland with trees for roosting and nesting as well as habitats frequented by large mammal [23].

Tall grassland and shrub land habitats increased bird species richness, evenness and distribution [22]. A past study indicated that successful breeding of bird species increases significantly with grassland size thus affecting positively species richness as well as diversity over an area [21]. Similarly, the results of this study showed that grassland and habitats affected positively bird species richness and evenness when compared to riverine habitats and negatively when compared with woodland habitats [2]. Grassland habitats always provide herbaceous cover for nesting, foraging as well as providing cover for bird species during winter and migration seasons thus affecting positively species bird richness hence high diversity [24].

Previous studies Zhou [25] and Tu [26] Indicate that aquatic habitats have higher species richness contrary to this study which urges that riverine habitats attracts unique bird community which affects negatively the overall richness and diversity of bird diversity when compared to grassland and woodland habitats. This means that, bird communities in riverine habitat are dominated by a certain species specifically water loving species and for this study we are directly referring to Zanzibar Red Bishop (Euplectes nigroventris) [27]. Aquatic bird species will always associate with aquatic animals for easy acquiring food materials including insects and worms (Shrusthi, 2016). Though the riverine habitats supported promising diversity and species richness of bird species in the ecosystem, it is worth mentioning that the habitat is crucial for survival of Marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumenifferus), one among the Vulnerable species in which if their habitats are lost they will ultimately be subjected to extinction risk [28].

Interestingly, forest habitat had the lowest species richness as well as diversity. This is due to the accumulation of generalists’ bird species, which finally affects negative diversity, and richness of bird species. Our result suggests that closed habitat, i.e. (Forest habitat) acts as a local environmental filter restricting the occurrence of large birds, e.g., Ground feeding insectivores thus affecting negatively the diversity and richness of bird species. Similarly, study conducted by Lee et al. [11], suggest that, assemblage of bird species at particular forest habitat is significantly correlated with assemblage of tree species. If there are few tree species accumulated at the same area formulating forest habitat, then it is obvious that the bird attracted will be of the same species thus affecting diversity and richness of bird species negatively [29-35].

Conclusion and Recommendation

Conclusively, the study provides insight information on the importance of multiple habitats in promoting conservation of avifauna in the PAs. The study suggests that mature trees formulating woodland habitat which is important characteristics for promoting species diversity and richness. The habitats provide daily needs of the bird species (nesting area, cover, food and shelter), thus attracting variety of bird species as the result, it affects positively diversity and richness of the respective areas. Additionally, the study recommends that more conservation efforts should be invested in protection of these habitats, which are very essential for avian assemblage. This will ultimately contribute to promoting avifauna tourism. Though some studies reveal grassland and bushland habitats as essential habitats for promoting both higher bird species diversity and richness contrary to this study, we recommend further research to be conducted in the same area based on wet and dry seasons.

References

- Kegamba JJ, Sangha KK, WurmP, Garnett ST (2022) A review of conservation-related benefit-sharing mechanisms in Tanzania. Global Ecology and Conservation 33: e01955.

- Mbise FP, Sosiya T (2023) Impact of outreach programmes on the relationship between local people and parks. Perceptions of communities near Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. Global Ecology and Conservation 42: e02411.

- Matolo RJ, Salia PJ, Nibalema VG (2021) Determinants of international tourists’ destination loyalty: empirical evidence from Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 10(3): 821-838.

- Gizachew B, Rizzi J, Shirima DD, Zahabu E (2020) Deforestation and connectivity among protected areas of Tanzania. Forests 11(2): 170.

- Brown L, Amutenya T (2024) Biodiversity finance in Namibia. ODI.

- Yihang H (2023) Relationship Between South African Nature Conservation Thought and Afrikaans Nationalism: Taking Kruger National Park as an Example. Journal of Beijing Forestry University (Social Science) 22(4): 83-89.

- Kegamba JJ, Sangha KK, Wurm PA, Kideghesho JR, Garnett ST (2024) The influence of conservation policies and legislations on communities in Tanzania. Biodiversity and Conservation 33(11): 3147-3170.

- Mramba M, Mrimi M (2024) Evaluating the Effectiveness of Anti-Poaching Efforts in Combating Wildlife Poaching at Udzungwa Mountains National Park, Tanzania. NG Journal of Social Development 14(2): 174-192.

- Nkwabi AK, Bukombe JK, Kija HK, Liseki SD, Ndimuligo SA, et al. (2021) Avifauna in relation to habitat disturbance in Wildlife Management Areas of the Ruvuma miombo ecosystem, Southern Tanzania. In Birds-Challenges and Opportunities for Business, Conservation and Research.

- Rajpar MN, Rajpar AH, Zakaria M (2022) Riverine forest as a significant habitat to harbor a wide range of bird species. Brazilian Journal of Biology 84: e256160.

- Lee PY, Rotenberry JT (2020) Relationships between bird species and tree species assemblages in forested habitats of eastern North America. Journal of Biogeography 32(7): 1139-1150.

- Mkwizu KH (2024) Experiences and enjoyment of national parks: study of Nyerere National Park in Tanzania. International Hospitality Review 38(2): 355-375.

- John J, Irmamasita D, Park SY, Choi CY (2024) Notes on Two, Inland and Island, Multi‐Species Heronries in the Northern Part of Nyerere National Park, Tanzania. African Journal of Ecology 62(4): e13348.

- Pratt DJ, Greenway PJ, Gwynne MD (1966) A classification of East African rangeland, with an appendix on terminology. Journal of Applied Ecology 3(2): 369-382.

- Okosodo EF, PM Sarada, GF Okosodo (2021) Bird Species and Flora Diversity, Conservation Strategies of a Degraded Amahor Forest Reserve Igueben Edo state Southwestern Nigeria. International Journal of Discoveries and Innovations in Applied Sciences 1(5): 1-12.

- Barnagaud JY, Flores O, Balent G, Tassin J, Barbaro L (2023) Trait‐independent habitat associations explain low co‐occurrence in native and exotic birds on a tropical volcanic island. Ecology and Evolution 13(7): e10322.

- Stevenson T, Fanshawe J (2020) Field Guide to the Birds of East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources – IUCN, 2018 [viewed 1 April 2019].

- Xiao H, Hu Y, Lang Z, Fang B, Guo W, et al. (2023) How much do we know about the breeding biology of bird species in the world? Journal of Avian Biology 48(4): 513-518.

- Okosodo EF, Solanke AS, Sokale AI, Ogundare AS (2022) Diet and feeding ecology of great blue turaco Corythaeola cristata for sustainable tourism in Urhonigbe forest reserve Edo state, Nigeria.

- Kavana DJ, Mbije N, Mayeji TS, Yu B (2024) Functional diversity of avian communities in response to habitat fragmentation in human‐dominated landscapes of Tanzania miombo woodlands. African Journal of Ecology 62(3): e13293.

- Briggs KB, Deeming DC, Mainwaring MC (2023) Plastic is a widely used and selectively chosen nesting material for pied flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca) in rural woodland habitats. Science of The Total Environment 854: 158660.

- Garbett R, Maude G, Hancock P, Kenny D, Reading R, et al. (2018) Association between hunting and elevated blood lead levels in the critically endangered African white-backed vulture Gyps africanus. Science of the Total Environment 630: 1654-1665.

- Mgelwa AS, Mpita MO, Rija AA, Kabalika Z, Hassan SN (2023) Avifauna community in a threatened conservation landscape, Western Tanzania: A baseline. Tanzania Journal of Forestry and Nature Conservation 92(1): 10-24.

- Zhou J, Zhou L, Xu W (2020) Diversity of wintering waterbirds enhanced by restoring aquatic vegetation at Shengjin Lake, China. Science of the Total Environment 737: 140190.

- Tu HM, Fan MW, Ko JCJ (2020) Different habitat types affect bird richness and evenness. Scientific Reports 10(1): 1221.

- Mugatha SM, Ogutu JO, Piepho HP, Maitima JM (2024) Bird species richness and diversity responses to land use change in the Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya. Scientific Reports 14(1): 1711.

- Gula J, Barlow CR (2023) Decline of the marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumenifer) in West Africa and the need for immediate conservation action. African Journal of Ecology 61(1): 102-117.

- Hanzelka J, Baroni D, Martikainen P, Eeva T, Laaksonen T (2023) Cavity-breeding birds create specific microhabitats for diverse arthropod communities in boreal forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 32(12): 3845-3874.

- Aldabe J, Sánchez-Iriarte AI, Rivas M, Blumetto O (2024) Managing Grass Height for Birds and Livestock: Insights from the Río de la Plata Grasslands. Rangeland Ecology & Management 92: 113-121.

- Barnard P, Brown CJ, Jarvis AM, Robertson A, Rooyen LV (1998) Extending the Namibian protected area network to safeguard hotspots of endemism and diversity. Biodiversity & Conservation 7: 531-547.

- Cooper TJ, Wannenburgh AM, Cherry MI (2017) Atlas data indicate forest dependent bird species declines in South Africa. Bird Conservation International 27(3): 337-354.

- Hill NJ, Bishop MA, Trovão NS, Ineson KM, Schaefer AL, et al. (2022) Ecological divergence of wild birds drives avian influenza spillover and global spread. PLoS pathogens 18(5): e1010062.

- Li X, Anderson CJ, Wang Y, Lei G (2021) Waterbird diversity and abundance in response to variations in climate in the Liaohe Estuary, China. Ecological Indicators 132: 108286.

- Titulaer M, Aragón Gurrola CM, Melgoza Castillo A, Camargo-Sanabria AA, Hernández-Quiroz NS (2024) Winter Bird Diversity and Community Structure in Relation to Shrub Cover and Invasive Exotic Natal Grass in Two Livestock Ranches in the Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico. Birds 5(3): 404-416.