Social Networks

Chris D Beaumont1*, Darrell Berry2 and John Ricketts3

1 Institute for Future Initiatives, LifeStylebyDesign, The University of Tokyo, Japan

2 Significance Systems, Brighton, UK

2 Significance Systems, Sydney NSW 2069, Australia

Submission: May 31, 2022; Published: June 17, 2022

*Corresponding author: Chris D Beaumont, Institute for Future Initiatives, LifeStylebyDesign, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan

How to cite this article: Chris D Beaumont, Darrell Berry, John Ricketts. Politics. Int J Environ Sci Nat Res. 2022; 30(3): 556291. DOI: 10.19080/IJESNR.2022.30.556291

Keywords: Narratives; Utility; Social sharing; Engagement; Behaviour; People; Big data; AI; Important; Emotional response; Improved decisions; Community; Interconnectivity

Context

Social Networks have, in recent years, become synonymous with social media and where communities with like-minded interests come to share and exchange. That said, with COVID-19 there has been a realignment with the support of local communities who with shared values provide informal and reciprocal support. Such bottom-up approaches could have perhaps been more directly engaged during the pandemic [1], but they remain a critical element of societal support especially with heightened inequalities and aging societies.

Social Networks

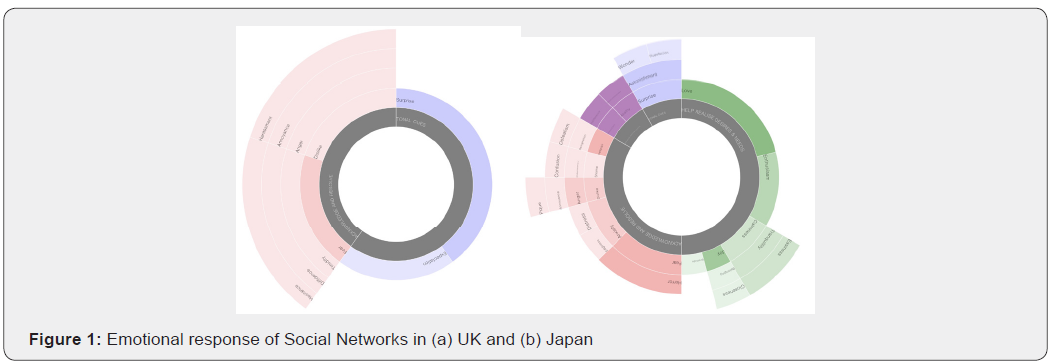

The social network narrative in the UK is timeless, with an affect orientation that is active and negative representing disgust, and as indicated such narratives tend to be polarizing, and their destructive nature needs to be addressed explicitly, if they are to be leveraged effectively to maximise their longer-term impact. In contrast the narrative projects a sense of delight by being active and positive, while also being timeless. There is recognition that not all information is valid and that while there are clear benefits in being better connected, fueling community, broader controls need to be considered with clear ethical considerations coming more to the fore. Wider access to new information sources does not necessarily provide more control or indeed a sense of being better informed (Figure 1 & 2).

In Japan there is a sharp dichotomy in terms of the nature of topics that drive engagement, some of which are relatively dated. There is strong positive association between gaining a world view and chat. In contrast, companies and word have a negative association since connectivity can create additional, and unwanted, pressure.

Implications

Social Networks are a widely used term in both the UK and Japan, but in both countries the content is different and diverse, with plenty of open opportunities for improved engagement. Connectivity is part of modern living, but it does not necessarily empower people with a greater sense of control, since expectations of improved responsiveness does create, for some, new lifestyle pressures. At present there is a sense of separation between digital and analogue social networks, in part a reflection of the need to dramatically change during the pandemic and new expectations.