Misaligned SDG Targets: How to Handle Target Dates Before 2030

Felix Dodds1,2*, Jamie Bartram2 and Gastón Ocampo3

1Tellus Institute & UNC Global Research Institute, USA

2Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering; University of North Carolina, USA

3Department of International Relations, Roanoke College, USA

Submission: June 11, 2019; Published: July 03, 2019

*Corresponding author: Felix Dodds, Tellus Institute, UNC Global Research Institute & The Water Institute at UNC, Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering; Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

How to cite this article: Felix Dodds, Jamie Bartram, Gastón Ocampo. Misaligned SDG Targets: How to Handle Target Dates Before 2030. Int J Environ Sci Nat Res. 2019; 20(2): 556034. DOI:10.19080/IJESNR.2019.20.556034

Abstract

Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted by the 193-member states of the United Nations in September 2015. It includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are accompanied by 169 targets, 107 of which are considered output targets and 62 are designated ‘means of implementation’.

While the SDGs are associated with the period 2016 - 2030, twenty-three targets (14%) have dates for completion before 2030. For twenty of those targets the date is 2020 and for the remaining three it is 2025. The affected targets are associated with 232 individual indicators. Not addressing the issues that arise because of this has the potential to create two classes of targets.

In most cases other UN processes will recommend continuation, modification, abandonment or replacement of expiring targets - outside the SDG framework. The updating of targets outside the SDG framework and therefore the emergence of two classes of targets has the potential to threaten the overall cohesion of the SDG enterprise; and there is some risk that resources will benefit one class of targets, those within the SDG framework, over the other, regardless of whether target conditions have been achieved.

The time window to prepare for the earliest-expiring target (2020) is short. We identify four option-types and summarize their pros and cons. None is perfect and some blend of them may be preferable. For all affected targets, monitoring is in hand within the SDG framework and in several cases established or potential processes would facilitate analysis and decision making as to abandonment, renewal, modification or replacement of targets and associated indicators.

“Sustainable development is the pathway to the future we want for all. It offers a framework to generate economic growth, achieve social justice, exercise environmental stewardship and strengthen governance [1].”

Keywords: Sustainable development; Maternal mortality; Technological expertise; Future

Abbrevations: MDGs: Millennium Development Goals; SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals; ACC: Administrative Coordination Committee; CEB: Chief Executives Board; OWG: Open Working Group; INC: Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee; WSSD: World Summit on Sustainable Development; SAICM: Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management

Introduction

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the predecessors to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were not adopted through a single intergovernmental agreement. The Millennium Declaration [2], adopted at the Millennium Summit in 2000, contained a statement of values, principles and objectives for the international community for the twenty-first century. The UN Administrative Coordination Committee (ACC) of the UN Secretary General, now known as the United Nations System Chief Executives Board (CEB), set up an interagency committee to develop the outcomes from the Millennium Summit into what became the MDGs and their associated targets and indicators [3].

The MDGs were established for the period 2001 to 2015 and, according to the final MDG Report: “the 15-year effort has produced the most successful anti-poverty movement in history:

a) “Since 1990, the number of people living in extreme poverty has declined by more than half.

b) “The proportion of undernourished people in the developing regions has fallen by almost half.

c) “The primary school enrolment rate in the developing regions has reached 91 percent, and many more girls are now in school compared to 15 years ago.

e) “The under-five mortality rate has declined by more than half, and maternal mortality is down 45 percent worldwide.

f) “The target of halving the proportion of people who lack access to improved sources of water was also met [4].”

Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted by the 193-member states of the United Nations in September 2015. It includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), accompanied by 169 targets, 107 of which are considered output targets and 62 are designated ‘means of implementation’.

One of the critical differences between how the MDGs and SDGs were developed was that the SDGs emerged from a global consultation involving governments, UN Agencies and Programmes, and stakeholders. The process included two high level panels set up by the UN Secretary General.

One of these, the High-Level Panel on Global Sustainability, established in August 2010 and publishing its report, Resilient People, Resilient Planet: A Future Worth Choosing in January 2012 as input to the UN Conference on Sustainable Development - known as Rio+20, recommended that:

“Governments should agree to develop a set of key universal sustainable development goals, covering all three dimensions of sustainable development as well as their interconnections. Such goals should galvanize individual and collective action and complement the Millennium Development Goals, while allowing for a post-2015 framework. An expert mechanism should be established by the Secretary-General to elaborate and refine the goals before their adoption by United Nations Member States [5].”

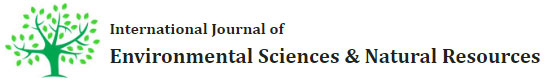

The second high-level panel was the Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, set up in July 2012 and which reported on the 30th of May 2013 put forward some suggestions about what those SDGs might look like and proposed 12 goals which will be found in Table 1.

The Rio+20 Conference held in June 2012 played a critical role in establishing the argument for the SDGs. The establishment of the Open Working Group (OWG) is outlined in the Rio+20 outcome document titled “The Future We Want” was poignant in the creation of the SDGs:

“248. We resolve to establish an inclusive and transparent intergovernmental process on sustainable development goals that is open to all stakeholders, with a view to developing global sustainable development goals to be agreed by the General Assembly. An open working group shall be constituted no later than at the opening of the sixty-seventh session of the Assembly and shall comprise thirty representatives, nominated by Member States from the five United Nations regional groups, with the aim of achieving fair, equitable and balanced geographical representation. At the outset, this open working group will decide on its methods of work, including developing modalities to ensure the full involvement of relevant stakeholders and expertise from civil society, the scientific community and the United Nations system in its work, in order to provide a diversity of perspectives and experience. It will submit a report, to the Assembly at its sixtyeighth session, containing a proposal for sustainable development goals for consideration and appropriate action [5].”

The Open Working Group would have 70 countries sharing the 30 seats and would meet 13 times to agree 17 goals and 169 targets. In 2015 the formal work of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) would then absorb these into the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which Heads of State would agree to in September 2015.

During this whole process there was also the most extensive input the UN has seen from stakeholder conferences, workshops and reports. All these informing member States as they started to negotiate. There were several key reports that in addition to the High-Level Panel put forward a set of suggested Sustainable Development Goals

Perhaps the most significant event was the United Nations Department of Public Information 64th Non-Governmental Conference held in Bonn in September 2011 called Sustainable Communities Responsive Citizens. The conference occurred only two months after Colombia had proposed the idea of the SDGs at an intergovernmental workshop in Solo Indonesia. The UNDPI NGO Conference proposed 17 sustainable development goals. These can be seen in Table 1.

The other major contribution was through the Sustainable Development Solution Network (SDSN). The SDSN has been operating since 2012 under the auspices of the UN Secretary- General. SDSN mobilizes global scientific and technological expertise to promote practical solutions for sustainable development, including the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Climate Agreement. Its report An Action Agenda for Sustainable Development published in June 2013 suggested 10 SDGs – see Table 1 [9].

The 2030 Agenda recognized and honoured several processes that were parallel to or preceded the SDG negotiations. These included the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 [10]; the Addis Ababa Action Agenda [11]; the existing target in the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) for the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) [12], and targets agreed in the processes around the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Biodiversity Targets for the period 2011-2020 [13].

While the SDGs are associated with the period 2016 - 2030, twenty-three targets (14%) originating in these other processes have dates for completion before 2030. For twenty it is 2020 and for the remaining three it is 2025. While processes that will lead to recommendations concerning some of these are underway, there is no consistent approach to decision-making about their continuation, modification, abandonment or replacement within the 2030 Agenda.

In this paper we describe the targets affected; review how analogous circumstances have been handled previously and describe the principal options available to policy makers. The paper is based on consultations with member States, the UN system and stakeholders. We hope to assist member states thinking and options they might have how to address these targets.

Status of affected goals and targets

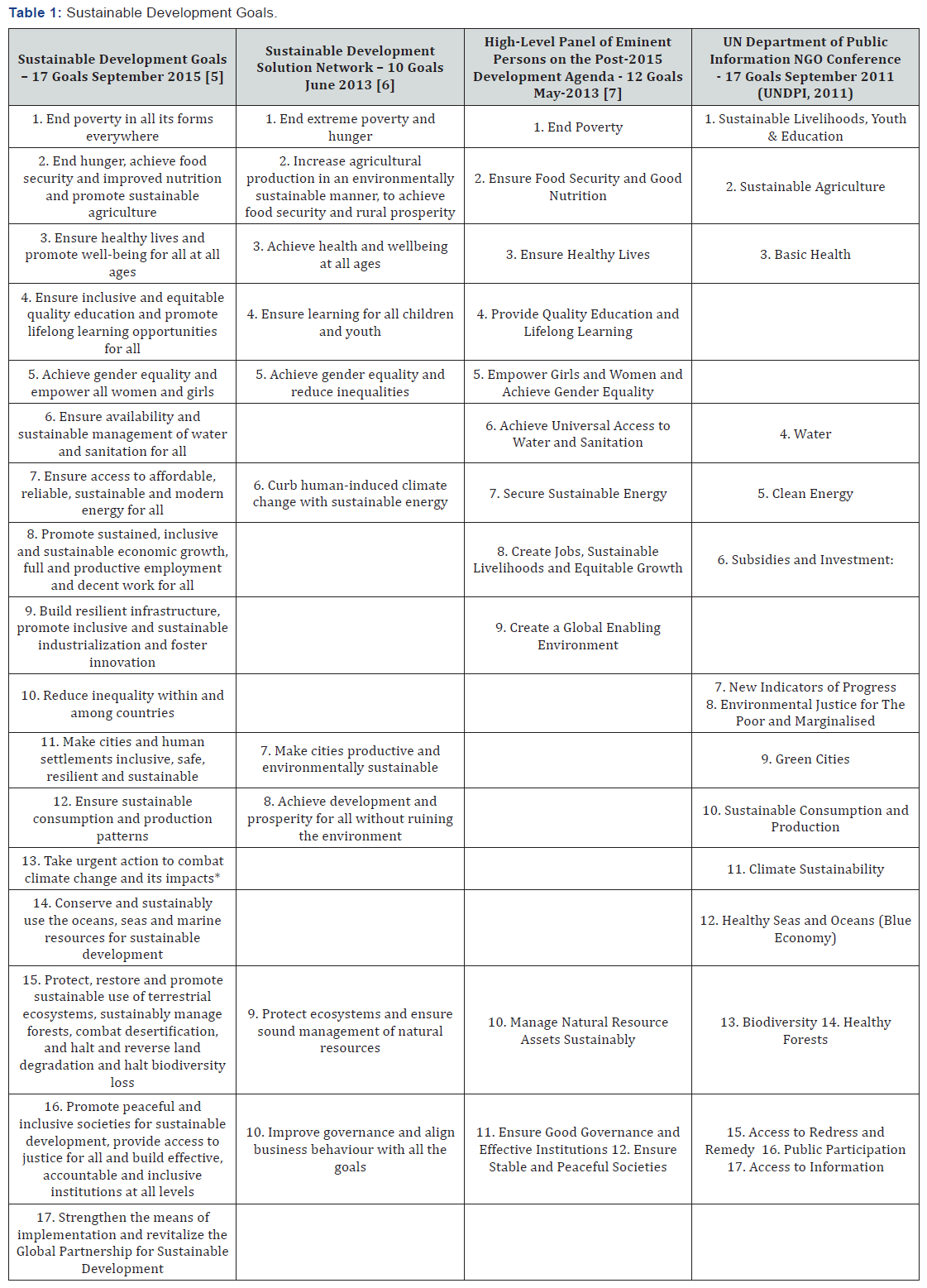

Table 1 lists the affected goals and targets, summarises associated monitoring and reporting activities, and notes for which targets a process to deliberate on post-target date activity has been identified. While five of the affected targets are nominally MoI (4b, 8b, 9c, 11b, 13a) their wordings more closely resemble outcome targets [14].

All the affected targets are subjects of monitoring and reporting. However, baseline information was available on the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform to inform the initial formulation of the SDGs and associated targets [15]. The availability of the associated insights; and of experience accrued with the monitoring efforts themselves, will give Member States baseline data and information on progress to inform discussion and to assist in determining whether these targets and their associated indicators should be continued, modified, abandoned or replaced with new ones.

Adoption of indicators for SDG targets was overseen by the United Nations Statistical Commission which “created the Inter-agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators (IAEGSDGs), composed of Member States and including regional and international agencies as observers. The IAEG-SDGs was tasked to develop and implement the global indicator framework for the Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda. The global indicator framework was developed by the IAEG-SDGs and agreed upon, including refinements on several indicators, at the 48th session of the United Nations Statistical Commission held in March 2017” [16]. This framework was adopted by the UN General Assembly [17]. The indicators are classified into three tiers:

a) Tier 1: Indicator is conceptually clear, has an internationally established methodology and standards are available, and data are regularly produced by countries for at least 50 per cent of countries and of the population in every region where the indicator is relevant.

b) Tier 2: Indicator is conceptually clear, has an internationally established methodology and standards are available, but data are not regularly produced by countries.

c) Tier 3: No internationally established methodology or standards are yet available for the indicator, but methodology/ standards are being (or will be) developed or tested [18].

There are 244 indicators however nine of the indicators are repeated under two or three targets so there are only 232 unique indicators. Of the 232 indicators associated with the affected targets 93, 66 and 68 are Tier I, II and III respectively.

To help in the development and assimilation of new forms of data to support better indicators and monitoring, the UN Secretary General set up an Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development. It presented its report “A World That Counts” in November 2014. One of its recommendations was the establishment of a “World Forum on Sustainable Development Data to bring together the whole data ecosystem to share ideas and experiences for data improvements, innovation, advocacy and technology transfer [19]”.

This initiative was embraced by the UN Statistical Commission as a platform for intensifying cooperation with professional groups, such as information technology, geospatial information managers, data scientists, and users and stakeholders.

The first United Nations World Data Forum was hosted from 15 to 18 January 2017 by Statistics South Africa in Cape Town, South Africa. The second will be hosted by the Federal Competitiveness and Statistics Authority of the United Arab Emirates from 22 to 24 October 2018 in Dubai.

Comprehensive review of indicators will happen in stepwise, in 2020 and in 2024 after the Heads of State Reviews of progress in delivering the SDGs in 2019 and 2023 [20].

Options Analysis

Identifying a future course of action for each affected target will depend in part on SDG-wide policies and approaches; and in part on target-specific context, such as the existence of a treaty or other process. Alignment between these two influences will vary target-by-target.

One of us (FD) consulted the UN Agencies and Programmes listed in Table 2 and presented an earlier version of this table to the government Friends of Governance for Sustainable Development (FGSD, 2017) workshop on November 2nd, 2017 to solicit their thinking on what to do with the affected targets. The four-principal option-types, there and associated principal advantages and disadvantages, and target-specific options described here are synthesized from that process [21,22].

Option 1: That no updated targets will be added to the SDGs to replace those that have expired and monitoring and reporting will conclude at the date of the target.

a) Pros: The agreement on the SDGs and their targets was one that had balanced the interests of all member states and reopening this could cause that balance to be fractured.

b) Cons: Some of the targets will be updated by other forums and so then there will be refection of progress reported to the HLPF in line with the new target. This will be particularly relevant to the CBD and SAICM targets.

b) Cons: Some of the targets will be updated by other forums and so then there will be refection of progress reported to the HLPF in line with the new target. This will be particularly relevant to the CBD and SAICM targets.

a) Pros: the agreement on the SDGs and their targets was one that had balanced the interests of all member states and reopening this could cause that balance to be fractured. It also allows reporting on the targets even if other forums have changed them.

b) Cons: These not updated targets will not have been absorbed into the SDG targets and so it creates two classes of targets. One which is in the SDGs and one that isn’t. This is true for the CBD and SAICM targets. It may impact on the level of commitment to the new targets if they are not absorbed into the SDGs.

Option 3: Any updated target would need to be agreed through the UN General Assembly if it was to replace an expiring target.

a) Pros: This option recognizes that the UN General Assembly had agreed the SDGs and their targets so is the only ‘official body’ that can update them.

b) Cons: This could see the whole agreement reopen unless member states agree to recognize the agreements made in other forums. This still doesn’t address the targets that do not have other forums to set new targets. In these cases, option 2 could continue.

Option 4: That any updated target agreed by a relevant UN body substitutes the old target without going through renegotiation in the UN General Assembly. Where there is no authoritative UN body then it is done through the UN General Assembly.

a) Pros: This would address all the targets that are going to finish in 2020 and 2025.

b) Cons: This would open the SDG targets negotiations to Committee 2 of the UNGA to address those that have no plans to be replaced and this could be a difficult negotiation (Table 3) [23].

Conclusion

The existence of diverse target dates within the SDG package is a consequence of a process that recognized and honoured the diversity and richness of inputs to the SDG process and longestablished mechanisms that pursue the SDG ambition. In most cases, there are processes that will recommend continuation, modification, abandonment or replacement of expiring targets. If this is outside the SDG machinery, it will see the emergence of two classes of indicators. This has the potential to threaten the overall cohesion of the SDG enterprise.

There is some risk that resources will benefit one class of targets over the other, regardless of whether target conditions have been achieved. Inaction will tend to favour this and the time window before preparations towards the earliest-expiring target (2020) is short. We identify four option-types and summarize their pros and cons. None is perfect and some blenddetermined cased-by-case may be preferable. For all affected targets monitoring is in hand and in several cases established or potential processes would facilitate analysis and decision making as to abandonment, renewal, modification or replacement of targets and associated indicators.

References

- Ban Ki-Moon (2013) Secretary-General’s remarks at a G20 working dinner on Sustainable Development for All. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2000) United Nations Millennium Declaration. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2001) Annual overview report of the Administrative Committee on Coordination for 2000. Geneva, UN.

- UNDP (2015) The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2012) United Nations Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Global Sustainability Resilient People, Resilient Planet: A future worth choosing. New York: UN.

- United Nations (2015) Leadership Council on the Sustainable Development Solution Network, “Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals”. New York, UN.

- SDSN (2013) An Action Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York, SDSN.

- United Nations (2013) High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2015) Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030.

- United Nations (2015) Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, Addis Ababa.

- United Nations (2002), Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg.

- Convention on Biological Diversity (2010) the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Biodiversity Targets.

- Bartram J, Brocklehurst B, Bradley D, Muller M, Evans B (2018) Policy Review of the Means of Implementation Targets and Indicators for the Sustainable Development Goal for Water and Sanitation. Clean Water 1(3).

- United Nations (2016) Ensuring that No One is Left Behind: Unlocking MOI for SDGs and Creating an Enabling Environment. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2018) The 2018 UN Sustainable Goals Report. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2018) Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2017) Tier Classification of Global SDG Indicators. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2014) United Nations Secretary-General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development it presented its report “A World That Counts”. New York, UN.

- Institute for European Environmental Policy (2018) Review of the progress on SDGs in the run-up to UN HLPF. New York, UN.

- United Nations (1992) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. New York, UN.

- United Narions (2010) High-Level Panel on Global Sustainability to Create New Blueprint for Achieving Low-Carbon Prosperity in Twenty-First Century. New York, UN.

- United Nations (2018) IAEG history.

- UN Environment, National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans, Nairobi.