Abstract

This study aims to comprehend how the self-talk of frontline hotel staff affects their perspective of work performance, employing a middle-scale hotel in Amsterdam (the Netherlands) as a case study. The study involved conducting qualitative interviews with hotel staff members to explore the impact of self-talk on their work performance and stress levels. Results reveal a significant relationship between self-talk and employee performance. Positive self-talk was associated with high coping responses and improved performance, while negative self-talk led to poor responses. The findings of this study contribute to the existing literature on self-talk and performance by shedding light on the importance of addressing hospitality employees’ self- talk in the workplace. Furthermore, the results of this study are to be utilized as reliable literature to comprehend the existing relationship between self-talk and employees’ performance, as well as develop further investigation on incorporating self-talk strategies aimed to improve employees’ performance in the workplace.

Keywords:Hospitality; Hotel; Global economy; Businesses; Lodging; Event planning; Theme Parks; Transportation; Cruise Lines; Beverage; Travel; Tourism; Recreation

Abbreviations:EWP: Employee Work Performance; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; WRS: Work-Related Stress; FLE: frontline employees; ST: Self-Talk; IWP: Individual Work Performance

Introduction

This research treats self-talk and performance in hospitality, studying the frontline staff and discussing human perceptions and attitudes. The hospitality industry has long been a relevant part of the economy, as it employs millions of individuals around the world [1], offering essential services to the public, and contributing to the global economy’s gross domestic product [2]. To maintain such services, the hospitality industry must ensure the well-being of its most valuable asset, which are its employees [3]. Employees drive businesses’ distinctiveness and competitive advantage [4].

Employee work performance (EWP) is the tenet on which the economy is constructed, without which there is no bureaucratic performance, no team or unit performance, no national economic performance, and no Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [5]. EWP can be defined as all the individual behaviors that, in various degrees, contribute to or impede the corporate’s goals [5].

Stress is one factor that impacts employees’ well-being and performance [6], and it is generally defined as physical and psychological reactions to stressors [7]. Additionally, occupational stress is the harmful physical and emotional consequences when work requirements do not match a worker’s capabilities [8]. Stress comes from a combination of different factors called stressors. Stressors, such as the lack of personal resources acquisition, family conflicts, different cultures, demographics, or organizational stressors, cause diverse types of stress. The stress phenomenon is significant in the hospitality industry due to its characterization of low income, long hours of work, fluctuating work schedules, and high physical demands [9].

The hospitality sector ranked first in the global list of industries with the highest employee burnout rates (Statista, 2019), and 80% of hoteliers and employees reported feeling overwhelmed at work (Statista, 2019), especially those who occupy frontline positions. According to Sampson and [10], the requirements of frequent and continuous interaction with customers, dealing with their numerous requests, role ambiguity, complexity, and conflicting work demands are among the main contributors to higher work-related stress (WRS) among frontline employees (FLE). Moreover, FLEs are required to respond immediately to a plethora of competing, opposing, or conflicting requests and expectations for various services, all of which heighten the WRS. Consequently, stress has been widely investigated, categorized, and various approaches have been established to mitigate its impacts [11]. However, a different approach that may diminish stress has yet to be discovered, especially in the field of service provision, which is self-talk [12]. Stress can impact employees negatively [6] and contributes to nearly 90% of productivity losses, leading to financial losses. In the hospitality industry, it is estimated that this loss represents US$ 187 billion. Stressors and occupational stress are linked to employees’ perception of stress [6], which is impacted by their self-talk [13].

Additionally, they form one’s behaviors [12,14]. However, this topic requires more research, especially concerning employees’ self-talk and their perceptions and delivery of quality performance. Consequently, the problem to be studied is if and how the selftalk of hospitality employees impacts their perspective of work performance. The inseparability characteristic of the hospitality industry, the high requirement of emotional involvement and empathy from employees to achieve service excellence (Mouzaek et al., 2021), initiates the need to address if and how employees’ appraisal of stress, which is a function of their self-talk, impacts their ability to deliver quality performance.

Self-talk (ST) is self-expression made explicitly or implicitly. They are multifaceted in structure and appear to have at least informative and motivating purposes [12]. The power of self-talk has been widely investigated in Sports, Psychology, and Human Development due to its strength in shaping the way people perceive and react to adversity [12,15]. It was even revealed that people’s behavior could be altered by changing how they speak to themselves while facing highly stressful events [12]. However, the impact of these talks on the employees’ performance has yet to be widely investigated in hospitality. Self-talk impacts people’s perception of reality and determines their behavior. Based on that point of view, this research investigates the assumption that self-talk impacts the employees’ perception of stress, directly impacting their behavior and performance.

This study contributes to the effective practices of business, where proving that a link exists between the hospitality employee’s performance, their self-talk, and perception of stress would enable researchers to gain new insights on how to reduce occupational stress and accordingly enhance the employees’ performance. This can be done by altering those employees’ ST. Additionally, businesses may benefit from lowering the losses accompanying the phenomenon of stress, which are resembled in the nearly 90% productivity losses and the estimated US$ 187 financial losses in the hospitality industry [9]. The question underlined in this research is if and how the self-talks of frontline hospitality employees impact their perspective of work performance. This study aims to comprehend how the self-talk of frontline employees affects their perspective of work performance, employing a middle-scale hotel in Amsterdam (the Netherlands) as a case study. The study is built on the theory of stress transaction, in which [16] explore self-talk, stress, and performance.

This study is fragmented into five parts. The initial part broadly presents the topic, contextualizing the scope of the subject and highlighting its main objective. The second part is the literature review, which displays topics including the scope and importance of the hospitality industry, different hotel jobs, and occupations of employees, the concept of performance, its elements, and various measurement approaches. In addition to discussing the phenomenon of stress, its various types, its deterring impact on businesses, and the concept of self-talk concerning employees’ performance. The third presents the methodology, which is a qualitative design, represented in a case study mixed with a content analysis approach and the next part presents and analyzes the results obtained from the interviews with the subjects of investigation. Moreover, lastly, the conclusion of the research is presented.

Literature Review

The business of hotels falls under the extensive umbrella of the hospitality industry, an industry that is a primary driver in global value creation, constituting 10.3% of the global gross domestic product (WTTC, 2022) and contributing US$ 8.9 trillion to the world economy in 2019 [17]. Hospitality is often understood as a broad category within the service industry that integrates the restaurant and hotel business, tourists, and the planning of various recreation and event activities [18]. It mainly includes institutions aiming at creating customer satisfaction and fulfilling leisurely demands as opposed to fundamental ones, with sub-category fields such as lodging, event planning, theme parks, transportation, and cruise lines.

At the macro level, the industry is forecasted to boost economic prosperity by producing foreign exchange and raising various forms of government income. While on the micro level, it enforces employment, income, and revenue, thereby enhancing development [19]. Moreover, hospitality is regarded as one of the world’s major industries and is divided into four main categories: food and beverage, travel and tourism, as well as lodging and recreation [19]. All of which are displayed in the hotel business.

Hotel jobs are generally classified into three main types: administrative, supervisory, and operative (Surya, 2006); while the first two focus primarily on the management and support of operations, the third is mainly concerned with the provision of guest services that typically include high rates of personal interactions (Surya, 2006). Those operative positions are occupied mainly by the frontline category of the workforce.

A workforce generally comprises people who are willing and able to work [20]. Thus, it includes employed and unemployed personnel actively seeking employment [20]. This group includes categories of workers, embracing essential and frontline employees. The former is a concept used to describe various vocations of which frontline employees comprise a subcategory. Moreover, this category is very similar in characteristics to the labor market in general and constitutes 70% of all employees [21]. The categories of workers are defined by offering the general public essential services. However, what distinguishes frontline employees from blue-collar workers is their necessity for onsite labor provision, their frequent need to report physically to perform their duties, and their requirement to engage in more personal encounters [21].

The frontline category includes porters, concierges, housekeepers, servers and kitchen staff, health care professionals, truck drivers, police officers, and so on. Additionally, it comprises 43% of all employees. It typically includes the less educated, the less paid, a higher proportion of men, and the underprivileged minorities, particularly Hispanics and immigrants [21].

Employee work performance (EWP) is the cornerstone around which the entire economy is built, and the institutional, team, and economic performance and GDP are entirely dependent. It enables the institutions to achieve their objectives directly [5]. Murphy and Campbell first identified the construct’s domains in the 1900s, and extensive literature on the concept was introduced afterward [22].

Individual work performance (IWP) can be defined as the actions or behaviors people take to further the organization’s objectives [23]. The concept, consisting of several elements or dimensions, is an ethereal, latent construct that cannot be directly indicated or quantified [22]. However, its consisting elements, which vary from one professional context to the other, can be directly measured by several methods.

The concept of performance is relevant in various fields, such as occupational health, management, and the psychology of organizations. Researchers have conducted studies to evaluate and maximize employees’ productivity, avoid attrition, and define the elements of its evaluation [22].

There are three main pillars for IWP: (1) task performance, (2) contextual performance, and (3) counterproductive work performance. However, a fourth dimension should be added to the former three: adaptive performance [22,24,25]. Task performance is a subcategory defined as the competency with which a person accomplishes essential work duties [22]. This subcategory has other terminologies across different literature, including (a) Job-specific task proficiency, (b) Technical proficiency, (c) Role performance, and (d) Proficiency in performing central job tasks. Moreover, the indicators for measuring it include work quality, work quantity, completing job tasks, solving problems, work knowledge, and productivity [24].

Contextual performance is the individual actions that promote the psychological, social, and organizational contexts in which the technical core must operate [22]. Some terminologies are used interchangeably with this concept, such as (a) Organizational citizenship behavior, (b) Extra-role performance, and (c) Competence in general task types. This pillar includes behaviors that exceed formal work goals, and it has indicators such as communication, discipline, additional duties, proactivity, leading and developing others, motivation, commitment to duty, and interpersonal behavior [24].

Thirdly, counterproductive work behavior is any deliberate behavior endangering or hurting an organization’s or its members’ legal norms and interests and adversely affecting institutions and employees [26]. It encompasses actions such as (a) Substance misuse, (b) Theft, (c) Tardiness, and (d) Presenteeism [22]. Lastly, adaptive performance refers to how a person adjusts to changes in a work process or job assignments. The construct includes problem-solving, navigating unforeseen or ambiguous work situations, picking up new skills, and adjusting to other people or cultures.

Other dimensions such as creative performance and task proactivity have also been discussed in previous literature [22] as constructs of IWP, where the former is defined as behavioral representations of creativity, including the production of new and beneficial ideas, processes, and products. While the latter is reflected in the degree to which individuals act independently and in a forward-thinking manner to alter their work circumstances, job positions, or themselves [27,22].

Several approaches attempt to evaluate employees’ work performance. Each one has different advantages and disadvantages, fitting singular standards or even optimal approaches [5]. According to [22], the literature includes 486 estimates of work performance. In general, aspects including organizational dedication, job capability, work performance, attitude to work, and individual growth can be used to evaluate employees’ performance (Tsai & Wang, 2019). [5] mentioned that most organizations employ outcome-based performance metrics such as achieving goals; however, only when elements beyond the person’s control are primarily eliminated from consideration do these indications count as performance measurements as they cannot assess crucial parts of nontechnical performance aspects. For instance, [28] discuss the restrictions that can impact organizational results without necessarily reflecting the performance behaviors of employees. Those restrictions might be displayed as market circumstances that can directly impact the sales volume and profitability without necessarily reflecting any IWP involved. Thus, outcome-based metrics cannot reflect employees’ performance in this case.

A well-known assessment method is the individual work performance questionnaire (IWPQ), a tool first introduced by [25] in the Netherlands [24]. Literature on Management, Economics, and Organizational Psychology served as the foundation for the operationalization of the IWPQ scales, proposed by [22,24,25], which measures three significant dimensions of IWP; task performance, context-specific performance, and counterproductive work conduct [29,22].

Additionally, this construct builds on previous questionnaires that needed the comprehensiveness of measuring all dimensions of IWP, as the former solely focused on IWP losses due to impairments of employees’ health. For instance, the work limitations questionnaire, impairment, and work productivity questionnaire measured IWP in assessing absenteeism and presenteeism. Thus, they needed other aspects of IWP and, consequently, IWPQ was created to address the deficiencies of preexisting questionnaires, covering the entire spectrum of that methodology [29].

Other approaches for measuring IWP include the most recent developments in performance evaluation, such as work simulations, advanced technological performance surveillance systems, and ratings [5]. Technological performance assessment is based on utilizing big data to improve corporate operations; however, these systems track outcomes, such as the number of sales, rather than performance. At the same time, the idea behind work simulations is to evaluate employees’ performance in a fabricated context where they execute duties or use fake task resources (for instance, riding, employing a video simulator, and acting out a negotiation).

Accordingly, individual performance ratings will be employed in this study, which aligns with the leading research goal to test whether a relationship exists between the employees’ self-talk and their perception of performance. Moreover, the assessment is based on items derived from the IWPQ, which also relies on employee performance ratings [29].

Stress is a set of psychological and physical reactions to negative, but inescapable stimuli or circumstances [7]. The phenomenon contributes to billions of financial losses and 70% to 90% of productivity-related losses in hospitality jobs [9]. Moreover, in critical service provision sectors such as banking, every 1% rise in job stress decreases the employees’ performance by 52.7%, and vice versa (Ahmed & Ramzan, 2013). Stress exists in several types, including the EU “the good stress,” which includes mild levels of pressure, worry, or fright and leads to better work performance [7]. As well as the negative or hindering stress, such as hypo and hyper stress or distress in general.

Stressor factors occasion the stress. When related to occupational stressors, these factors could be categorized mainly into two groups. The first group is the Challenge stressors, linked to Eustress (good stress), which serves as a cause for encouragement and leads to favorable work outcomes. The second group is the Hindrance stressors, which are the energy-draining job demands that impair work engagement and productivity [7].

Contreras, Espinosa, and [30] state that personal resources also play a critical role in developing or preventing work-related stress. In contrast, the term is defined as identity aspects often associated with resilience and give people a sense of power and control over their environment, so they may successfully adapt. For instance, acquiring high self-esteem, high self-efficacy, and optimism protects against the development of burnout, which is one form of prolonged chronic stress.

Additionally, some personal resources, such as proactivity, reflexivity, assertiveness, and intrinsic motivation, are inversely related to burnout and serve as substantial coping factors that buffer the impacts of stress [30]. On the other hand, low selfesteem and low self-efficacy are harbingers to burnout. Mindset or self-theories also play a critical role in perceived stress or worry. [31] explain that our stress appraisal aligns with our belief systems or implicit self-theories. Those implicit theories can establish various psychological realities, causing individuals to think, act, and feel indifferently in similar circumstances [32].

Self-talk (ST) is a self-developed phenomenon that is defined as intrinsic or extrinsic dialogue in which the person develops with oneself, impacting their behaviors positively or negatively, depending on the nature of this dialogue [33]. As they encompass instinctive, impulsive ideas and verbalizations as well as intentional, strategic remarks spoken to oneself [34]. Self-talk can serve a variety of purposes, including assisting people in maintaining self-control over their actions, improving deliberate focus, and boosting self- esteem [35]. However, when negatively employed, they may result in heightened anxiety and depressive symptoms [15].

[36] stated that people get influenced by their interpretations of the world, not by the objective world itself, where it was displayed that the exact same situation can happen to multiple individuals; however, each one can perceive and react to the situation differently. This is not due to the difference of the situation itself, nevertheless, it is the individual’s representation and interpretation that makes it different. An influential factor in this distinctive interpretation is personal self-talk [34].

Personal self-talk is based on the principle that the way individuals talk to themselves impacts how they act (Ellis, 1976, as cited in [34]). The effectiveness of such principle is reflected in the major role that thoughts have on performance [37,38] and the massively employed mental strategies that were designed to intentionally change, guide, or control individuals’ thought patterns.

This was mainly witnessed in the field of sports, where such strategies are regarded as a main component for acquiring successful performance, in addition to having importance in the training of psychological skills of athletes. In this sense, ST is recognized as a command to start, carry out, or perform a series of actions, with their core highlighting how desirable thinking causes a desired action [35].

Self-talk leads to different interpretations and behaviors. STS is categorized into two main types: (1) Positive ST and (2) Negative ST. The former is the approach that serves to validate oneself by endorsing our own favorable characteristics or encouraging oneself [33]. While the latter is defined as detrimental self-talk, highlighting our failures, ineptitude, or personal harm [33].

Numerous pieces of literature have discussed the enhancing impact of positive ST on performance, including improved cognitive abilities such as decision-making and effective concentration (Kendall, Howard & Hays, 1989; Tod, Hardy & Oliver, 2011). In addition, according to Hatzigeorgiadis, Zourbanos, Mpoumpaki, and [35], positive impacts of STS were particularly displayed during times of adversity. For instance, in their study of young athletes, motivational self-talk was found to improve task performance and increase self-confidence, and, at the same time, decrease cognitive anxiety. Similarly, Hatzigeorgiadis et al. (2004) found that using STS during task implementation diminishes irrelevant thoughts and improves concentration, serving as cognitive functioning. This also aligns with the findings of Bandura (1977) as cited in Goudas, Hatzidimitriou, and [12], stating that positive ST is a form of verbal persuasion that comes from the self which enhances individuals’ self-efficacy and leads to promoted self-confidence.

A study of military recruits found that positive ST was linked to improved stress management and resilience (Morgan, Fletcher & Sarkar, 2019). The same findings were displayed in the study of DeCaro et al. (2010) as cited in [39], demonstrating that students employing positive ST while completing challenging academic work under stress better managed their tension and anxiety, and accordingly displayed an improved task performance, which shows the complementary impacts that positive ST have on academic performance. One interesting finding of [40] was that positive ST, specifically self-respect self-talk, can have both beneficial and detrimental impacts on performance. The first was displayed in improved motor and visual coordination, as well as the improved speed of processing and cognitive thinking of participants. While the latter was linked to higher displayed impulsivity resulting from heightened inaccurate confidence.

On the other hand, negative ST has an opposing detrimental impact. Where according to [15], this type of ST has been associated with mental diseases, and according to theories of cognition, they convey the contents of maladaptive schemas. For instance, it was found that adolescents with ADHD (Attentiondeficit/ hyperactivity disorder) reported engaging in more critical self-talk about themselves and that a connection exists between ADHD and derogatory self-talk in a clinical sample of young people. Similarly, it was found that positive correlations exist between depression, anxiety, and negative dialogues [41]. Hardy and [38] have also stated that negative STS is a sign of a poor self-concept. Which in return mediates the relationship between earlier academic success and later degrees of impairment due to changed symptoms of depressive and anxiety symptoms [16].

Previous studies have suggested that diverse forms of selftalk have different purposes, which was based on the notion that different ST cues lead to different performance impacts [35]. Accordingly, two main types of positive ST were found: (1) motivational and (2) instructional ST. The former seeks to increase performance by promoting a positive attitude, increasing self-assurance, effort, and utilization of energy, while the latter enhances behavior by eliciting the preferred performance with the appropriate attentional focus, approach, and strategy application [12].

Research Methodology

The research employed a qualitative method where it has been investigated if and how the self- talks of frontline hospitality staff impact their perspective of work performance. Moreover, this is an exploratory cross-sectional study, applying a single case study design that focuses on a rich description of the participants’ narrations [42], including content analysis for the narratives. This design has been chosen due to the high efficiency of case studies in exploring and providing a comprehensive understanding of a concept or phenomenon [43,44]. Additionally, Transactional, and Coping Stress Theory has been applied, which is one of the most conceptually prominent transactional paradigms in stress literature [6,16]. The theory states that stress can be found neither solely in the individual nor the situation [6], but in the transaction between both. Besides, there are two pillars upon which this theory is built: Cognitive Appraisal and Coping [6].

The study focuses on the appraisal element, which is the differentiating factor that dictates how individuals display various stress responses to the same stimuli or stressor. Appraisal, in that sense, is a very subjective process, dependent on people’s estimation of whether they can cope with the stressor [6]. According to Yan et al. (2021), this hypothesis states that the perception of the event as stressful, not the situation itself, causes stress and determines its coping method. In that sense, the research illustrates whether this subjective appraisal is the byproduct of the individual’s self-talk and whether their coping mechanism or performance is dependent on those narratives [6].

The study applied secondary data employing previous literature in scholarly articles and books to deeply understand the themes and capture subsidies for the preparation of interview forms. To provide primary data, a semi-structured, open-ended interview script was conducted, a qualitative research method that entails holding lengthy one-on-one conversations with a select few respondents to learn about their perspective on a specific concept, program, or circumstance [45]. Personal interviews were employed due to the method’s usefulness in extracting deep information and knowledge about a person’s beliefs and behaviors and its effectiveness in exploring novel issues that outperform other data collection techniques, such as surveys [45].

Key phrases and words established categories, data points, and themes. This information is supported by the stories of the participants [42]. The interviews were conducted physically at the hotel and were recorded by audio and video with the previous consent of the participants. Additionally, participants were attained after conducting a pilot test.

This study has employed specific criteria for selecting participants that include: (1) Participants belonging to the frontline hospitality, (2) Staff were questioned about their frequent experience of stress and their development of self-talks that are work-related. The interviews had a semi- structured script with open-ended questions, encouraging long narratives of the interviewees to align with the content analysis framework [46].

The population of this study comprises hospitality frontline staff from a medium-scale hotel in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The hotel belongs to an international hotel chain. It offers 644 standard rooms. Besides the rooms, the only service provided by the hotel is the breakfast. A small number of participants was selected (8 Food & Beverage Frontline Team Players) and the sample consisted of full-time and part-time workers chosen randomly by convenience. The research employed a minor number of participants as a sample, whereas, unlike the quantitative approach, the goal of qualitative research is to acquire a comprehensive picture of each person or phenomenon [47]. Accordingly, purposive sampling was applied with a focus on a small number of participants to acquire knowledge about the investigated phenomenon [47], not generalizing the findings [47], but to deepen the understanding of the results. The sample size was settled based on the data saturation. Saturation is the golden standard in qualitative research, as it is the point at which no novel codes, no new information, and no new patterns emerge [46], translating into the termination of data generation [46]. According to [48], there are three stages of saturation: (1) data, (2) themes, and (3) codes. Moreover, all three-saturation stages should occur simultaneously. Accordingly, the point at which data is saturated is mostly the same point at which codes and themes will reach the saturation terrain [48].

Interviewees were asked to sign an informed consent declaration, in which they were informed about their rights of complete voluntary participation, of stopping or withdrawing their data at any point in time, and that their personal data were going to be kept highly confidential. The forms did not contain the respondents’ names in order to safeguard their privacy; thus, each participant was nominated by two letters. The likelihood of biases and subjectivity, which may emerge when respondents are aware that their identities may be used to support the data, is also thought to be decreased by maintaining the respondents’ anonymity.

After the data collection, all the information in the transcript was entered into a digital document. The textual data has been coded applying two methods: Inductive and deductive approaches. The initial coding process starts with a theory or pertinent research findings, and the deductive technique is based on previously specified, theoretically determined categories [49]. The next stage is choosing key concepts based on preexisting theory or prior research. Previous studies have assisted in creating a systematic interview with set categories, i.e., Stress Primary and Secondary Appraisal, Contextual Performance, Task Performance, Instructional and Motivational ST, Negative ST, and Coping Appraisal.

The data analysis was conducted by Atlas-it software, software for analyzing qualitative data, especially for large amounts of text, visual, and aural data [50]. Each file was given prefixes to protect the respondents’ confidentiality. This process was followed by a thorough analysis to code and categorize each document, which entailed several reconstructions and changes to the coding patterns aiming to enhance the investigation and results. The number of codes ranged approximately between 36-50 codes for each interview transcript, and the findings have been explained in word clouds displaying the most frequent key terms found in the interview transcripts for each question and verbatim to reaffirm information and ideas.

Findings

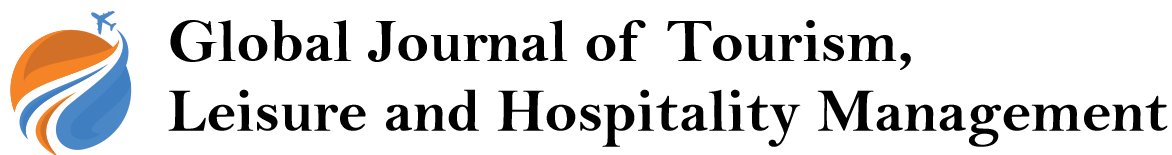

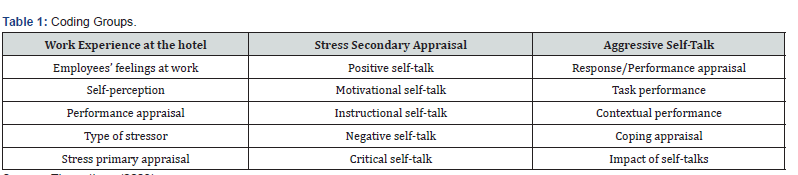

The variables and significant conceptions were determined as coding categories based on the review of the literature and interview questions. The coding groups consisted of Figure 1 displays the most frequent keywords found in the responses of employees in their descriptions of their work experience at the hotel. The most frequent keywords were “nice colleagues” (five times), “I like it” (five times), and “Stressful experience” (three times). In addition, some other common keywords included “Different nationality of workers” (two times) and “Experiencing inconsistent workload” (two times). Furthermore, some interesting key terms also comprised “Unprofessional colleagues” 4:12 a8 in AS and “Cheap employees” 4:61 11 in AS.

While describing their feelings at work. Participants reported feeling “Stressed at work” (five times), some stated that they “Like their job” (four times), and “Witnessing consistent changes in operations” (four times). Another prevalent keyword was the “Different nationality of workers” (five times). Other common keywords were, “I like it, but it is stressful” (three times) and “Unfriendly atmosphere” (two times). In addition, some interesting sayings also included “short staffed” 11:12 24 in AG, “Backstabbing co-workers” 9:42 19 in AN, “Culture barriers of communication” 6:18 23 in NR, 9:28 17 in AN. And an outlier whose description of the hotel was, a “Dull workplace” 4:62 24 in AS and a “Profit-seeking organization”4:59 20 in AS Figure 2.

From the previous data, it is concluded that the main codes used upon describing the hotel’s atmosphere and employees’ experience were; “Positive work experience” (seventeen times), which was resembled in keywords such as “yeah, I like it” (nine times) 3:7 9 in HR, “nice colleague” (eight times), “we have a nice team” 3:8 9 in HR Figure 3. And “Negative work experience” (eleven times), “Negative feelings at work” (eleven times), “Stressful (eight times), “it can be stressful sometimes” 5:52 21 in HB, “consistent changes in operations” “There were always modifications happening in this department” 9:40 20 in AN. As well as, “different nationality workers”, “I work with people from different culture, origins, and languages” 6:3 11 in NR (seven times each).

Most of the keywords are positive; however, some of the staff express negative narratives, for instance, “Unprofessional colleagues” and “Inconsistent workload” Figure 4. From these questions, it is possible to assert that employees have different work experiences, despite working for the same company. The different employees’ perception is also reflected in the internationalism of colleagues, as for some it is advantageous, while for others it is negative, as it brings barriers to communication. To sum up, the data indicates the stressful yet favorable and diverse work environment that the hotel has from the employees’ perspective Figure 5.

Illustration 2 elaborates on the key phrases identified by the respondents while stating their self-perception. The most frequent key phrases were “Positive, helpful, honest, and hard worker” (three times each). Another frequent self-perception was “Development oriented” and “Trying to achieve the best performance” (two times each). And some interesting descriptions were, “The best employee” 10:17 16 in HJ and “Boring” 4:19 14 in AS. To conclude, most of the respondents (seven) held a positive self-image, and one outlier solely had a negative self- image stating that he is “boring” 4:19 14 in AS. It is worth mentioning this outlier also had a detrimental work perception, “a dull workplace” 4:62 24 in AS, and had further engaged in negative self-talk 4:74 38 in AS.

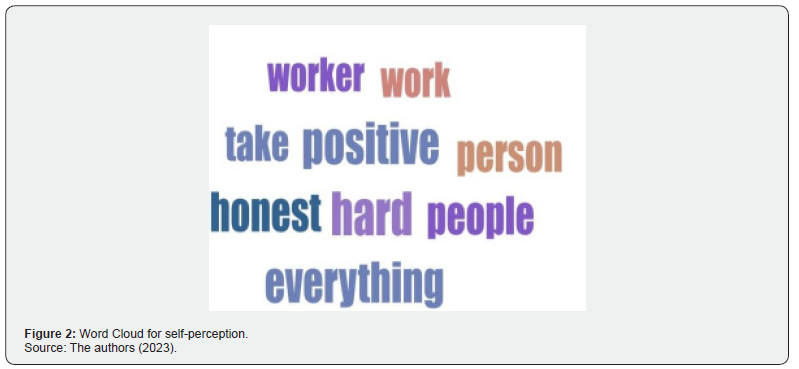

The previous figure illustrates the most frequent general performance appraisal displayed by the respondents and their justification for such evaluation. The most frequent keyword was an “8” (five times). In addition, most of the participants (six) rated themselves as good performers “from 8.0 to 8.5”, while comparatively one reported seeing himself as a low performer “7” 3:70 15 in HR and one stated being a high performer “9.5” 8:41 18 in AY. It shows that even at low performance, the average evaluation is good. It demonstrates also they feel confident about the work they are providing.

Furthermore, while listening to the respondents’ justification of performance appraisal, the most frequent key terms were “Not showing best performance” (five times) “Because I am not showing my full performance” 4:37 19 in AS, “I am not perfect” (four times) 9:23 17 in AN, “Trying to achieve best performance” (four times)10:15 16 in HJ, “taking extra tasks” (two times) and “efficiently managing difficult situations” (two times). Some interesting responses were “emotional regulation” 8:43 18 in AY, “I don’t like my job” 3:18 18 in HR and “unprofessional people”4:28 19 in AS. An interesting observation was that among the six participants who rated themselves as moderate performers “8” and “8.5” 10:59 18 in HJ, the key words “not showing best performance” appeared four times followed by “I am not perfect”(three times).

To conclude, from the above three questions seven out of the eight participants perceive themselves positively, out of which six have moderately appraised their performance, due to two main reasons displayed in their imperfection and not showing their best performance.

Illustration 5 displays the most used key phrases by the participants upon describing the type of stressor that they were subject to. The most frequent ones were interpersonal mistreatment (four times), for instance, “co-workers have told me go fuck yourself you bloody Gypsy” 4:41 26 in AS, and “I felt they were accusing me that I am the one who took it” 5:18 24 in HB, followed by labor intensive task stressors (two times), “I cannot do such labor intensive tasks” 3:62 26 in HR, and short staffed (two times), for instance “I was all by myself in that department” 9:43 22 in AN. In addition, among singular keywords were “misuse of authority”, “was using her authority against me” 3:65 26 in HR, “backstabbing co-workers” 6:20 26 in NR, “Co-worker went to the management and said that I am complaining and disappearing from my position, it was really unfair” 6:20 26 in NR and “consistent changes in operations” 10:30 25 in HJ.

Based on these findings, it is possible to understand that resembled in the interpersonal communication between colleagues and the workload is the most frequent stressors at the workplace and a company that wants to avoid stressors, should focus on these two main areas in their policies. These are consistent with the findings of [9], stating that ‘job characteristics’, including sub criteria such as “coworker relationships” and “inconsistent work schedule”, are among the top-ranking stressors in hospitality.

Figure 6 illustrates the most used keywords by the participants while describing their stress primary appraisal, those were threat (four times) as in the sentence “I felt helpless and threatened” 6:22 29 in NR and challenging (three times) as in the statement “I saw it as a challenge” 8:25 27 in AY. Moreover, one outliner had a non-stressful primary appraisal 9:65 22 in AN Figure 7.

The result of this question indicates that most participants (half of them) perceived the stressful situation as potentially harmful, threatening, or negative to themselves or their abilities whether physical, emotional, or psychological, as opposed to a minority (three) who perceived it as a challenge and an opportunity to grow. These two sides of stress were identified by [7] when they stated that stress can be advantageous or detrimental.

Illustration 7 shows the most frequent key phrases found in the responses of the study sample. Which included feeling anger (three times) 3:33 33 in HR and self-protection (two times) 6:57 32 in NR. Upon analyzing the responses of the sample, half of the participants have reported a lack of resources secondary appraisal, such as “I wanted to defend myself in English I could not” 6:54 32 in NR, or “I thought I could not open the door because I wasn’t strong enough”8:46 29 in AY, while the remaining half reported sufficient resources secondary appraisal, for example, “I was immediately thinking about the solution I guess” 9:1 28 in AN and “this is too much work but I need to finish as fast as I can” 11:42 36 in AG.

The majority (three) of respondents who had a “threat primary appraisal” had a lacking secondary appraisal. On the other hand, some (three) of those who displayed “challenge primary appraisal” showed a sufficient secondary appraisal, which indicates that the majority of those who viewed the stressor as a threat had the belief that they lacked the efficient resources to handle the situation. Most of those who perceived it as an opportunity to learn, believed that they had the sufficient resources to resolve the situation.

According to Figure 8, the most frequent key phrases offered by the respondents was positive self-talks (five times), followed by negative self-talks (four times). Out of the former, instructional self-talk was the most frequent (4 times) as AG stated that “I told myself I will first finish and then talk to the management” 11:32 36 in AG, followed by motivational self- talk, “you can do it” 8:49 31 in AY (3 times) in total. An interesting phenomenon was seen in the combined approach of instructional and motivational selftalks that was employed by two of the respondents when they answered “you can do it” 8:49 31 in AY (motivational), “you do not have to stress, stress isn’t good for u” 8:51 31 in AY (instructional) and “I need to finish as fast as I can” 11:31 36 in AG (motivational), “I told myself I will first finish and then talk to the management” 11:32 36 in AG (instructional). Both are forms of positive selftalk.

Another observation was in the responses of three participants who reported having no self- talk. However, during their narration they indirectly reported having one: “No there was nothing at all” 11:30 36 in AG (no self-talk), “I just thought this is too much work but I need to finish as fast as I can” 11:33 36 in AG (having an ST). “No” 10:34 33 in HJ (no self- talk), “They told me this ok this is my job I will do it” 10:56 36 in HJ (having an ST), and “there was no dialogue that popped in my mind” 4:46 35 in AS (no self-talk), “I said to myself those idiots do not know what to do, and I will get in trouble because they were under my watch” 4:74 38 in AS (having an ST). The data indicates that almost half the participants initially did not realize the existence of their internal dialogue and consequently its potential impacts on their performance.

For the negative self-talks, critical and aggressive self-talks were the most frequent (two times), “I said no I won’t tolerate her anymore” 3:66 37 in HR, which implies self-criticism for tolerating the other person’s behavior for a long time. The other was “Those idiots do not know what to do” 4:67 38 in AS. Negative labels such as “idiots” have been used to describe colleagues, and the speaker assumes they don’t know what to do without their guidance, which suggests a critical behavior. In addition, “I will take him outside and beat him up” 4:45 35 in AS, “one more thing and I am going to slap her” 3:37 37 in HR, both suggesting physical violence.

An outlier employed both positive and negative self-talks; the positive was displayed in “I told myself to keep calm and not react emotionally or say anything that can be misunderstood by the managers” 6:31 35 in NR, which is an instructional self-talk to regulate emotions. The negative was “I just kept telling myself, it is because of my bad English that I could not communicate properly” 6:31 35 in NR, which conveys a self-deprecating self-talk in the form of a negative self-image about their language hindrance, leading to feelings of helplessness, and low self-esteem.

To sum up, the positive self-talks were reported more than the negative ones, with the domination of instructional ST (four times), followed by motivational (three times), then aggressive and critical ST (two times), which indicates the positive approach employed by most employees while facing the stressors, even without realizing it by themselves.

The previous illustration (Figure 9) shows the main key phrases employed by the respondents while describing their response to the stressful event. Half of respondents have employed problem-focused coping (4 times), while the other half have utilized emotional-focused coping (4 times). Problem-focused coping relies on taking actions to solve the stress source, which was displayed in “I tried to have a talk with my leader” 11:36 38 in AG, “I called my friend because I thought I can’t open it myself” 8:31 34 in AY or “I just ignored the situation that was happening in the kitchen” 9:58 34 in AN Figure 10. The former two examples illustrate asking for help to remove the stressor. While the latter reflects actively ignoring or suppressing the source of stress, to focus on practical tasks and responsibilities.

On the other hand, emotional-focused coping relies on regulating the emotions that are accompanied with the stressor without particularly addressing the issue at hand. Examples of this were shown in “I smoked a whole pack of cigarettes to calm my nerves” 4:47 38 in AS, “I made sure I stayed calm although I was getting pissed off and irritated” 5:28 39 in HB and “from the outside I did my work properly but from the inside everything was not fine” 6:56 38 in NR. All of which indicate emotional regulation Figure 11.

Lastly, it was found that participants who employed problemfocused coping did not necessarily have “sufficient resources” secondary appraisal, and vice versa. Half of the respondents (two) who had a lacking-secondary appraisal utilized problem-focused coping, and half of those who displayed sufficient secondary appraisal utilized emotional-focused coping, which contradicts with the findings of [51,52], where, it was stated that individuals who lack the resources to respond to the stressor, are most likely to utilize emotional-focused coping. For those believing in their capacity to manage the situation, problem-focused coping is most likely to be utilized. However, this finding cannot be generalized to other hotel employees due to the small number of participants taking part in this study Figure 12.

The illustrations above display the most frequent key responses reported by the participants while rating their performance and coping satisfaction to the stressor. While rating their response/coping rating to the stressor, the most frequent reply was high coping rating, for instance “10” 4:52 44 in AS and “9” 8:34 40 in AY” (four times each), followed by comparatively moderate “7.5” and low rating “6” 3:45 45 in HR 9:61 and 39 in AN (two times each). It is also shown from the illustration that coping satisfaction was reported by the majority of participants (five times), which implies participants’ contentment about the way that they responded to the stressor, with “high task performance” demonstrated as the most frequent code (three times) displayed in “I did my job properly and I finished on time” 10:39 39 in HJ and “I managed to finish all the work and I checked everything before I left” 11:35 41 in AG. The responses were followed by “high contextual performance” (two times), displayed in “I think I responded in a very nice way and that’s how I am” 4:71 41 in AS and “When my colleagues were asking me I responded to them in a nice way and I refrained from being arrogant to them, which is what my managers would expect of me” 5:29 39 in HB. Both participants felt resentment for responding too nicely to the situation 4:68 41 in AS and 5:33 43 in HB. However, professionally they displayed high contextual performance, reported coping satisfaction, and showed high to moderate coping rating “10” 4:52 44 in AS and “8” 5:34 46 in HB.

An interesting response was having a coping satisfaction while at the same time displaying low contextual performance during the stressful experience. The respondent elaborated having “outcome satisfaction” rather than coping performance satisfaction, “I was satisfied with the outcomes because there was no damage” 9:75 37 in AN. Nevertheless, they gave themselves a low coping rating “6” 9:61 39 in AN and low contextual performance due to their initial avoidance of the problem “because I ignored at the beginning this problem and only focused on the guests” 9:63 39 in AN. Thereof, it is to be regarded as coping dissatisfaction. On the other hand, a minority of participants reported coping dissatisfaction (two times). Moreover, among the interesting key words were feeling helpless 6:38 41 in NR and low task performance 3:67 42 in HR [53].

To conclude, the number of respondents who took action to remove the stressors equated those who only attempted to regulate their emotions towards them. Additionally, most respondents (half) have highly appraised their coping performance, five have reported being satisfied with their displayed stress response, which was mostly evident in their high task performance (three times) and high contextual performance (two times). These findings do not fully align with the theory of stress and coping, where the theory states that individuals with sufficient secondary appraisal are most likely to display problem-focused coping, while those with lacking appraisal normally employ emotionalfocused coping. In the findings, however, it was seen that most respondents with the lacking appraisal (three out of four) have indeed displayed emotional- focused coping, with one exception. Nevertheless, the ones displaying sufficient appraisal were equally divided into two showing emotional-focused coping and the other two displaying problem-focused coping [54].

The figure above illustrates the most frequent key phrases disclosed by the respondents to remove the stressor, which was a rebuttal question aiming to get richer data from the participants. Seven out of the eight participants attempted to later remove the stressor. Where “Talk with the management” was the most frequent key phrase (four times), “I sent an email to the HR and a formal complaint” 4:73 26 in AS and “I wrote everything down and I went to the management to complain” 3:46 48 in HR. Another key phrase was “emotional regulation” 6:42 45 in NR. Additionally, an outlier reported having no attempt at resolution, “nothing is going to change” 10:58 40 in HJ, indicating acceptance for the persistency of the problem.

The previous illustration (Figure 13) shows the keywords in the participants’ responses, where the most common one was the respondent’s conformation for the self-talk impact (seven times), “Yeah I think it affected me of course” 3:68 52 in HR and “Yes” 8:37 46 in AY, all of whom reported that the self-talk led to their response at least at that moment of stress, “Yes, just for that moment” 6:43 48 in NR. It was directly reported that the selftalk has led to a better performance (two times), “It affected in a positive way” 8:39 46 in AY, and “ the story made me give my best”10:48 42 in HJ and led to a poor performance (two times) as here: “The fact that I said I do not want to go inside had directly led to me to postpone handling the situation” 9:70 ¶ 43 in AN, and “if I had told myself otherwise, I would have reacted better and not made a scene in front of the other guests” 3:69 ¶ 52 in HR Table 1.

An interesting reply was “Denial of self-talk impact” 4:55 49 in AS; however, upon further investigation the respondent indirectly reported having a self-talk, as displayed in the sentence “I said to myself those idiots do not know what to do, and I will get in trouble because they were under my watch” 4:74 38 in AS, which impacted their response to the stressor, “I went outside calmed myself down and came back to work” 4:57 50 in AS, despite the participant stating otherwise. Seven out of eight participants have directly confirmed the impact of self- talks on their behavior and coping to the stressor, which is regarded as their performance in this study. Moreover, it has been directly stated by most participants (four) that the type of self- talk led to a coping response of similar type, that is the positive self-talk led to a high coping response, while the negative self-talk led to a poor response.

Conclusion

This study aimed at investigating if and how the self-talks of individuals impact their perception of work performance employing the frontline hospitality employees of a mid-scale hotel in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. To reach the research aim, semistructured interviews were conducted with front-office employees. It has been found that the self-talk of frontline hospitality employees has a direct impact on their work performance and yields a response of similar type to the employed ST. That is, the positive self-talk resulted in high to medium appraised coping performance, while the negative self-talk led to dissatisfaction and poor performance in both cases participants’ behavior towards stressors were directly impacted by their employed ST. These results are consistent with dominant previous literature on the topic. Further research should be conducted to test the hypothesis on a larger population in other hotels in Amsterdam. Further suggestions include providing training to frontline hospitality employees on positive self-talk strategies which can improve their coping and overall work performance. Lastly, future research could explore additional factors that may influence such impactdeveloping interventions to support employees in managing their self-talk for optimal performance.

References

- Han JW (2020) A review of antecedents of employee turnover in the hospitality industry on individual, team and organizational levels. International Hospitality Review 36(1): 156-173.

- Pang K, Lu CS (2018) Organizational motivation, employee job satisfaction and organizational performance: An empirical study of container shipping companies in Taiwan. Maritime Business Review 3(1): 36-52.

- Dwesini NF (2019) Causes and prevention of high employee turnover within the hospitality industry: A literature review. African Journal of Hospitality Tourism and Leisure 8(3): 1-15.

- Heimerl P, Haid M, Benedikt L, Scholl Grissemann U (2020) Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction in Hospitality Industry. Sage Open 10(4).

- Campbell JP, Wiernik BM (2015) The modeling and assessment of work performance. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2(1): 47-74.

- Kuforiji OA (2017) Qualitative study exploring Maternity Ward Attendants’ perceptions of occupational (work related) stress and the coping methods they adopted within maternity care settings (hospital) in Nigeria, University of Bradford, UK.

- Wang JS, Fu X, Wang Y (2020) Can “bad” stressors spark “good” behaviors in frontline employees? Incorporating motivation and emotion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 33(1): 101-124.

- Tantawy A, Abbas TM, Ibrahim MY (2016) Measuring the relationship between job stress and service quality in quick-service restaurants. Egyptian Journal of Tourism Studies 15(2).

- Vatankhah S, Bouzari M, Safavi HP (2020) Unraveling the fuzzy predictors of stress at work. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 29(2): 277-300.

- Sampson WG, Akyeampong O (2014) Work-related Stress in Hotels: An Analysis of the Causes and Effects among Frontline Hotel Employees in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. J Tourism Hospit 3(2).

- Heath C, Sommerfield A, Von Ungern Sternberg BS (2020) Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anesthesia 75(10): 1364-1371.

- Goudas M, Hatzidimitriou V, Kikidi M (2006) The effects of self-talk on throwing- and jumping-events performance. Hellenic Journal of Psychology 3(2): 105-116.

- Morgan PB, Fletcher D, Sarkar M (2013) Defining and characterizing team resilience in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 14(4): 549-559.

- Ulatowski J, Zyl L (2020) Virtue, Narrative, and Self Explorations of Character in the Philosophy of Mind and Action. Routledge, UK.

- Castagna PJ, Calamia M, Davis TE (2017) Childhood ADHD and Negative Self- Statements: Important Differences Associated with Subtype and Anxiety Symptoms. Behav Ther 48(6): 793-807.

- Herman KC, Reinke WM, Eddy CL (2020) Advances in understanding and intervening in teacher stress and coping: The Coping-Competence-Context Theory. Journal of School Psychology 78: 69-74.

- Stafford MR (2020) Connecting and Communicating with the Customer: Advertising Research for the Hospitality Industry. Journal of Advertising 49(5): 505-507.

- Vakhovych IL, Matviichuk L, Smal B (2021) Development of the Hospitality Industry in Modern Conditions: Trends and Measures to Strengthen Competitive Advantages. Financial & Credit Activity: Problems of Theory & Practice 6(41): 494-502.

- Ampofo JA (2020) Contributions of the hospitality industry (Hotels) in the development of WA municipality in Ghana. International Journal of Advanced Economics 2(2): 21-38.

- Castillo MD, Unit CDWDP, Chief DWDPU (2011) labor Force Framework: Concepts, Definitions, Issues and Classifications. ILO, presentation on Spain. CBS (2002). Nepal Labor Force Survey I, Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics. CBS (2008). Official Statistics of Nepal, Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics. CBS (2014).

- Blau FD, Koebe J, Meyerhofer PA (2021) Who are the essential and frontline workers. Bus Econ 56(3): 168-178.

- Koopmans L, Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, Schaufeli WB, Henrica V, et al. (2011) Conceptual frameworks of individual work performance: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 53(8): 856-866.

- Koopmans L, Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, De Vet HCW, Van der Beek AJ (2014) Measuring Individual Work Performance: Identifying and Selecting Indicators 48(2): 229-38.

- Fernández del Río E, Koopmans L, Ramos Villagrasa PJ, Barrada JR (2019) Assessing job performance using brief self-report scales: The case of the individual work performance questionnaire. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 35(3): 195-205.

- Koopmans L, Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, Van Buuren S, Van der Beek AJ, et al. (2014a) Improving the individual work performance questionnaire using Rasch analysis. J Appl Meas 15(2): 160-175.

- Wang HY, Chen ZX (2022) A moderated-mediation analysis of performance appraisal politics perception and counterproductive work behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 928923.

- Fluegge Woolf ER (2014) Play hard, work hard: Fun at work and job performance. Management Research Review 37(8): 682-705.

- Motowidlo SJ, Kell HJ (2012) Job Performance. Handbook of psychology: Industrial and organizational psychology, (2nd edn). John Wiley & Sons, pp. 82-103.

- Koopmans L, Coffeng JK, Bernaards CM, Boot CR, Hildebrandt VH, et al. (2014b) Responsiveness of the individual work performance questionnaire. BMC Public Health 14: 513.

- Contreras F, Espinosa JC, Esguerra GA (2020) Could personal resources influence work engagement and burnout? A study in a group of nursing staff. Sage Open 10 (11).

- Lee HY, Jamieson JP, Miu AS, Josephs RA, Yeager DS (2019) An entity theory of intelligence predicts higher cortisol levels when high school grades are declining. Child Dev 90(6): 849-867.

- Dweck CS (2000) Self-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. Psychology Press.

- Thomaes S, Tjaarda IC, Brummelman E, Sedikides C (2020) Effort self-talk benefits the mathematics performance of children with negative competence beliefs. Child Development 91(6): 2211-2220.

- Hase A, Hood J, Moore LJ, Freeman P (2019) The influence of self-talk on challenge and threat states and performance. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1534.

- Hatzigeorgiadis A, Zourbanos N, Mpoumpaki S, Theodorakis Y (2009) Mechanisms underlying the self-talk–performance relationship: The effects of motivational self-talk on self- confidence and anxiety. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 10(1): 186-192.

- Wilson T (2011) Redirect: The surprising new science of psychological change. Penguin UK.

- Gould D, Eklund RC, Jackson SA (1994) 1998 US Olympic Wrestling Excellence: Mental Preparation, Precompetitive Cognition, and Affect. Sport Psychologist 6(4): 358- 382.

- Hardy J, Hall CR (2006) Exploring coaches’ promotion of athlete self-talk. Hellenic Journal of Psychology 3(2): 150-163.

- Sánchez F, Carvajal F, Saggiomo C (2016) Self-talk and academic performance in undergraduate students. Anales De Psicología 32(1): 139-147.

- Kim J, Kwon JH, Kim J, Kim EJ, Kim HE, et al. (2021) The effects of positive or negative self-talk on the alteration of brain functional connectivity by performing cognitive tasks. Scientific Reports 11(1): 1-11.

- Alsaleh M, Lebreuilly R, Lebreuilly J, Tostain M (2016) The relationship between negative and positive cognition and psychopathological states in adults aged 18 to 20. Journal de thérapie compartmental et cognitive 26(2): 79-90.

- Campbell S (2014) What is qualitative research. Clinical Laboratory Science 27(1): 3.

- Kumar R (2011) Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners. 3ed Sage, New Delhi, India.

- Lindgren BM, Lundman B, Graneheim UH (2020) Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies 108: 103632.

- Boyce C, Neale P (2006) Conducting in-depth interviews: A guide for designing and conducting in-depth interviews for evaluation input. Watertown, MA: pathfinder International Tool Series Monitoring and Evaluation 2.

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, Young T (2018) Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1): 1-18.

- Komolthiti M (2016) Leadership journeys: A narrative research study exploring women school superintendent's meaning-making of leadership development experiences. A Doctoral Dissertation Presented at Northeastern University, USA.

- Fusch PI, Ness LR (2015) Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 20(9): 1408.

- Swain J (2018) A hybrid approach to thematic analysis in qualitative research: Using a practical example. London, Sage Publications.

- Smit B, Scherman V (2021) Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software for scoping reviews: A case of Atlas. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20(69).

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1987) Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality 1(3): 141-169.

- Walinga J (2019) Health and Stress. In: Cummings JA and Sanders L (2019) Introduction to Psychology. Saskatoon. SK: University of Saskatchewan Open Press.

- Koopmans L (2014) Measuring individual work performance. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Muzaek E, AL Marzouqi A, Alaali N, Salloum SA, Aburayya A, et al. (2021) An empirical investigation of the impact of service quality dimensions on guest’s satisfaction: A case study of Dubai Hotels. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government 27(3): 1186-1199.