Abstract

Keywords:Kimberly Mehlman Orozco, PhD in Criminology, Law and Society, George Mason University, USA

Introduction

In recent years, several hospitality organizations have started to disseminate speculative materials on how hoteliers can combat human trafficking. However, these training and educational programs are typically not based on empirical evidence and their reliability is unknown, if not questionable. Instead of focusing limited resources on potentially ineffective training that would likely lead to remarkably rates of false positives, hospitality leaders should consider redirecting anti-trafficking efforts toward burgeoning evidence-based interventions, such as computer vision technology [1].

Disseminating Misinformation

Hospitality leaders should be cautious about untested and speculative training programs because organizations that train the hospitality industry are known to cite misinformation. For example, on the prevalence of trafficking1 and the average age of victims2, as well as purported “red flags” of trafficking, and appearance or demographic of victims or offenders. The dissemination of misinformation results in interventions with low rates of sensitivity and specificity.

A human trafficking “red flag” training with low specificity can be criticized as being too eager to find a positive result, even when it is not present, which could result in false accusations/ investigations of human trafficking against law abiding citizens.

Knee-Jerk Response to a Non-Existent Epidemic

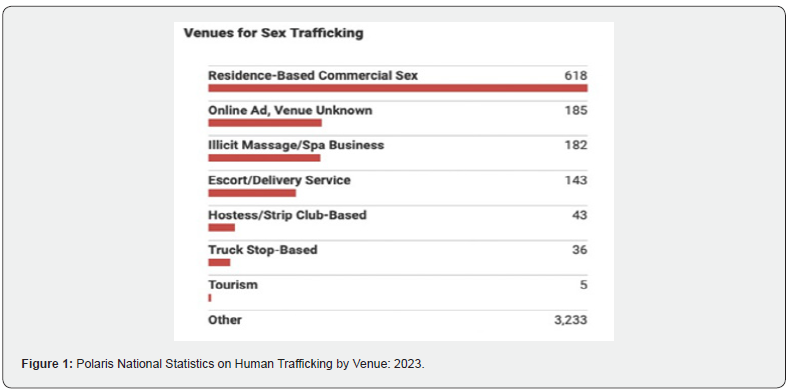

Speculative trainings started to be increasingly disseminated among the hospitality industry in mid-2016 in response to unsupported allegations that sex trafficking was occurring at “epidemic levels” in the hospitality industry [2]. However, available data suggests there may be much fewer incidents of trafficking in the United States than some organizations are alleging. For example, trafficking in “tourism” venues is rarely reported to the Human Trafficking. Hotline (4-12 reports per year since 2007) (Figure 1).

Speculative Interventions with Unlikely Efficacy

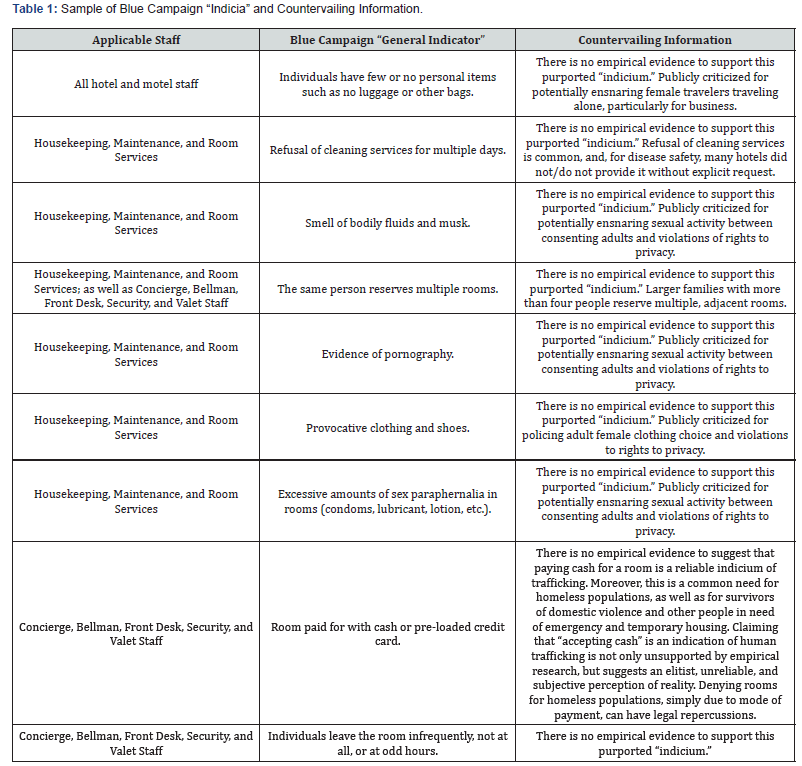

The reality is that the available toolkits which claim to facilitate trafficking prevention and identification in the hospitality industry are typically based on unsupported speculation and subjective belief. For instance, the Blue Campaign’s hospitality toolkit includes several “general indicators,” which at present lack any empirical support Table 1.

Ultimately, given the lack of qualitative or quantitative evidence to support the efficacy of these “indicia” and interventions, they should be applied cautiously, if at all. While these “indicia” have not been adequately empirically tested, extant reliable principles and scientific methods suggest that implementation and training of these “indicia” will have no bearing on a business’ ability to prevent, identify, or intervene against human trafficking on premises and may result in high rates of false accusations [3].

Evidence-Based Interventions

Instead of focusing on the dissemination of speculative training that has no empirical basis, hospitality leaders should explore the use of recently developed evidence-based interventions, such as computer vision and artificial intelligence to maximize the benefits of extant security cameras. According to James Connor, Head of Corporate Engagement at Ambient.ai, AI technologies deliver “an evidence-based solution that prioritizes both security and privacy” with proactive threat identification and risk reduction.

Essentially, companies like Ambiet.ai continuously mine security cameras for safety threats and can automate alerts to management, private security companies, and/or law enforcement. For example, outdoor cameras can detect the presence of a firearm and alert staff before it even reaches the inside of a building [4].

Conclusion

For anti-trafficking efforts to be effective in preventing crimes and facilitating identification and intervention of offenders and victims, it is imperative to place resources with evidence-based interventions instead of speculative programs, which lack any empirical basis.

References

- Kessler G (2015) The fishy claim that 100,000 children in the United States are in the sex trade. Washington Post, USA.

- Kessler G (2015) Why you should be wary of statistics on modern slavery and trafficking. Washington Post, USA.

- Kessler G (2021) The Four-Pinocchio claim that on average, girls first become victims of sex trafficking at 13 years old. Washington Post, USA.

- Savoie E, Su M, Leffler A, Hughes D, Spurrell W, et al. (2024) A Quasi-Experimental Intervention Trial to Test the Efficacy of a Human Trafficking Awareness Campaign: The Blue Campaign. Journal of Human Trafficking, pp. 1-20.