What is Expected from a Regional Entity Managing a Tourist Destination? Definition of Functions Based on the Analysis of the Relationship with Stakeholders, Their Needs and Expectations: Functionality and Dysfunctionality

Octavi Bono i Gispert*

Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Vila-seca, Catalonia-Spain

Submission:September 23, 2024;Published:October 04, 2024

*Corresponding author: Octavi Bono i Gispert, Rovira I Virgili University, Vila-seca, Catalonia-Spain

How to cite this article: Octavi Bono i Gispert. What is Expected from a Regional Entity Managing a Tourist Destination? Definition of Functions Based on the Analysis of the Relationship with Stakeholders, Their Needs and Expectations: Functionality and Dysfunctionality. Glob J Tourism Leisure & hosp manag. 2024; 2(2): 555583. DOI:10.19080/GJTLH.2024.02.555583.

Abstract

The study analyzes the functions of a regional Destination Management Organization (DMMO) in Catalonia, considering legal regulations and interaction with stakeholders. Using qualitative documentary analysis, the needs and expectations of both public and private stakeholders were examined, identifying their influence on the functions of the DMMO. The methodology focused on 1,020 records of meetings, conducted between 1998 and 2016, analyzing the origin and type of stakeholders, their motivations, and expectations. This analysis was contrasted with the legal competencies defined in the Tourism Law of Catalonia and the statutes of the Tourist Board of the Tarragona Provincial Council (PTDT). The results reveal that the functions most in demand by stakeholders are marketing and promotion, representing more than 50% of the interactions. At the same time, areas such as planning and sustainable management receive less attention. Furthermore, 62% of stakeholders are private, highlighting the tendency to prioritize business needs. In conclusion, the current functions of the DMMO are more influenced by stakeholder demands than formal competencies, suggesting a mismatch that may affect the sustainability and governance of tourism management.

Keywords: Destination Management; Governance; Competencies; Roles; Stakeholders

Introduction

In Catalonia, the organizations responsible for managing tourist destinations (Destination Marketing and Management Organisation, DMMO) at a local level have their functions defined by various regulatory frameworks. The most relevant are the Tourism Law 02/2002 and the statutes themselves in the case of autonomous organizations. Others also assign powers, the Local Rules Law and its subsequent amendments, but do not detail in the same depth the responsibilities and tasks to be developed. These regulations are a guide to frame what can and should be carried out from a competence-based, general and theoretical perspective, but it is a fact that the functions are readjusted based on a series of other aspects: capacities and skills of the teams, available resources, leadership and vision of those responsible and especially the relationship with the actors (stakeholders) of the ecosystem that makes up the destination.

The simple enumeration of competencies in a standard does not determine the degree of effort distributed among them for their execution, nor does it allow to identify whether new ones are generated beyond those that are related.

Stakeholders can contribute to shaping the framework of tasks and functions based on their own concerns and needs, transferring some elements and not others, and also based on their expectations given that they expect a certain type of response. This generates, in relation to the tasks and functions of the DMMO, a situation that is articulated on a double level: normatively defined responsibilities and responsibilities derived from the relationship with the stakeholders of the destination and their influence. The aim of this research is to identify what perspective of the responsibilities and tasks of a DMMO is held by the network of stakeholders and what adjustment is made to the formally defined framework. To do so, evidence is taken from the summaries of the meetings held between the head of a local entity (provincial in scope) and the stakeholders of the destination over a long period of time between 1998 and 2016. The analysis of this evidence allows to identify the origin (public or private) of the actors, their nature according to the type of organisation they are, the typology of the motivations that lead to generating a contact, as well as the expectation of a result derived from that contact. These elements condition the functions of the DMMO and allow to identify whether adjustments are made and how the formally assigned competencies operate.

Literature Review

A holistic conceptualization of the idea of a tourist destination leads to defining it as a location with a set of products and experiences, critically influenced by the role of the attitudes of existing companies and their willingness to cooperate [1,2]. Organizations responsible for their management are deployed around tourist destinations and until the early 1990s there was relatively little research on tourist organizations as a specific topic. Douglas Pearce's book Tourist Organizations (1992) began to fill this gap in the literature, representing the first exhaustive and systematic treatment of tourist organizations in which their functions, operations and reason for being were described. Very soon, the work was able to distinguish, at least at a national level, the basic activities of tourism organizations: coordination, legislation, promotion, research and tourist information. However, in order to cope with the changing situation of a destination, it was already defined that organizations should adopt alternative functions, that is, development, marketing, management and innovation, according to the growth pattern of each destination. This process would be continuous as a destination progressed through successive product life cycles reflecting the changes to meet the new needs of visitors and the community [3]. Gartrell[4] is also one of the first academics to analyse the functions of destination management organizations and identifies the following tasks:

i. Coordination of the many constituent elements of the tourism sector (including local, political, civic, business and visitor representatives) to achieve a single voice for tourism.

ii. Fulfilling both a leadership and tourism promotion role within the local community it serves. The DMMO should be a visible entity that draws attention to tourism so that residents of the destination understand the importance of the visitor industry.

iii. Help ensure the development of an attractive set of facilities, events and tourism programs, and an image that helps position and promote the destination as competitive in its experiences.

iv. Assist visitors by providing visitor services such as pre-visit information and additional information upon arrival.

v. Finally, the DMMO also has another important role, serving as a key liaison to assist external organizations, such as meeting planners, travel wholesalers and travel agents working to bring visitors to the destination.

vi. Subsequently, the study of the functions of the DMMO has been dealt with more broadly. Some authors [5], have categorized five major areas of action:

i. "Community marketing" to project the destination image, attractions and facilities best suited to targeted visitor markets

ii. “Industry Coordinator”, to provide a clear focus and encourage less fragmentation of the industry to share the growing benefits of tourism.

iii. “Economic boost,” to generate new revenue, employment and taxes and contribute to a more diversified local economy.

iv. “Quasi-public representation” to legitimize the sector and protect individual visitors.

v. “Building community pride” by improving quality of life and acting as a primary advocate for both residents and visitors.

For Bornhost, Ritchie and Sheehan [6] the functions of the DMMO, in their broadest terms, are: to work to improve the well-being of destination residents; to do whatever is necessary to help ensure that visitors receive visit experiences that are at the very least, highly satisfactory and, where possible, highly memorable; and, at the same time, to ensure effective management and stewardship of the destination. Later [7], based on a very intensive review of other scholars makes a detailed analysis of functions and categorizes a total of eleven: community builder, mediator, stakeholder coordinator, stakeholder representative, public representative, sustainability officer, economic driver, networker, product developer, destination planner and connection channel with the outside [8]. recognizes that the work of a DMMO is highly complex since it not only involves carrying out marketing actions, but also involves understanding all the needs of the destination and the actors, stakeholders, who operate in it.

From there, it establishes that the functions of a DMMO revolve around sustainable competitiveness that must lead to guaranteeing coexistence in the destination, derived from the satisfaction of the tourist and the benefit perceived by the resident thanks to the activity that is generated, acting as an impartial coordinator that manages the resources of the destination, represents the interests of the actors of the activity and seeks to improve competitiveness through a proactive role in the development of tourism. The power relations that they sustain and how they influence the collaboration processes are fundamental to address the importance of stakeholders, that is, the degree to which those responsible for DMMOs give priority to the claims of interested parties is key to effectively develop strategies to achieve shared objectives [9]. The importance of stakeholder interaction was already pointed out by Jan Kooiman, professor emeritus at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, when he defined governance as “the patterns and structures that emerge in a socio-political system, as the common result of the interactive intervention efforts of all the actors involved” [10,11] distinguish the importance of stakeholders because they provide the superstructure and the tourism product, participate in its programs or support them in general, influence governance or provide or facilitate financing. This last aspect, that of financing, may be the result of the unique dynamics of Canada where they focused their research.

They also suggest that the success of collaboration between stakeholders depends largely on mutual understanding between them [12] also identify the importance of personal relationships and communication with leaders of key stakeholder organizations; managing stakeholder perceptions of DMMOs, especially as they relate to the influence of vested interests in the destination; creating transparency regarding DMMOs and their operations; and the importance of DMMOs as a guarantor of promotional resources and ideas or opportunities across a network of stakeholders in the destination. These comments point to the critical importance of social relationships of DMMO management teams in the strategic management of stakeholder relationships. It is interesting to keep in mind a vision such as that of Dr. Goran Hyden, professor emeritus of the Department of Political Science at the University of Florida, who established in 2003 that governance is “the formation and custody of the formal and informal rules that regulate the public sphere, the sphere in which state, economic and social actors act to make decisions” Hyden G, et al. [13], distinguishing between a double level, formal and informal, of norms. This double dimension can also be seen when defining competencies. In the context of a tourist destination, the position of the stakeholders, and the groups or conglomerates of organizations from the different subsectors of the destination will influence the power dynamics that can affect the success of the destination or hinder it [14].

Objective and Methodology

Aim

This research aims to understand the real scope of the functions of a regional (provincial) entity responsible for the management of tourist destinations based on the needs and expectations of its network of stakeholders, contrasting it with the formally defined competency framework to identify the degree of adjustment or mismatch that occurs.

Methodology

Qualitative documentary research has been proposed based on the analysis of the registration documents of the content of the meetings carried out between 1998 and 2016 by a regional DMMO with those stakeholders who had on their own tendered the meeting. The analysis of this evidence has been carried out to identify the origin (public or private) of the actors, their nature according to the type of organisation they are, the territorial link to the destination, the typology of the motivations that lead them to generate a contact, as well as the expectation of a result derived from that contact. Each unit of analysis has been each of the registration documents. When the data was incomplete, the record in question has been rejected. Valid records of 1020 meetings have been obtained.

Documentary studies often require effort when translating existing records into quantifiable indices of some general concepts. Therefore, in order to define the list of possible motivations, as well as expectations, a categorization exercise was carried out based on the review of the first 100 records. The categorization led to a subsequent definition exercise to clearly detail the scope of each concept and thus facilitate the analysis of the set of documents. The analysis of the set of documents led to expanding the initial list of motivations and expectations. In meetings where several actors participated (except in the case of groups of tourist boards), the person leading the topic to be discussed was recorded. If several categories of topics were discussed at a meeting, the one considered to be the main one was recorded. Finally, the identified data was aggregated to generate an overall conceptual view. Document analysis allows to collect data in an orderly manner, analyze the data and offer logical results, with a list of specific objectives in order to build new knowledge. has formulated quality control criteria for the management of documentary sources. These are: authenticity, credibility, representativeness and significance. It is important to mention that the quality control formula for the management of documentary sources exists and must be met. However, these dangers are not more pronounced in the documentary research method than in other research methods. Each research method has its strength and weakness [15].

In parallel, the legal and regulatory framework that defines the provincial competences of the destination management bodies has been analysed and the relationship with the category of identified motivations has been established. Having this documentary material, and with the existing volume, represents a good opportunity to empirically analyse, from the observation of the facts, a reality that often requires theoretical approaches based on surveys.

Area of study

The research focuses on the analysis of the functions of the Tourist Board of the Tarragona Provincial Council (PTDT), a local entity with provincial scope responsible for the management of the Costa Daurada and Terres de l'Ebre destinations located in the south of Catalonia. The Costa Daurada has an area of 2,999 km2. In terms of tourism, it is characterized by the majority of the offer concentrated on the coastal strip, its high specialization towards the family segment, the presence of a highly qualified leisure offer that has its greatest exponent in PortAventura World, the value of some of its heritage assets (Cister and Tarraco) and the configuration of an inland territory where vineyards and wine tourism are the protagonists. The main asset in relation to natural spaces is the Montsant natural park. Its marketing is highly internationalized.

The Terres de l'Ebre, located in the southernmost part of Catalonia, is characterised by its high natural value and the low intensity of tourist activity both on the coast and inland. It has an area of 3,306 km2, of which 47% is protected. Among these are the Ebro Delta Natural Park and the Els Ports Natural Park. The presence of the largest river in the Iberian Peninsula, the Ebro, still shapes an area of unique characteristics that has earned it the declaration as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO. Its marketing is mainly oriented to the domestic market.

Together, they generated a total of 20,421,000 overnight stays in 2023, resulting in the arrival of 5,643,000 tourists. These figures are already very similar to those achieved in 2019 (20,972,000 overnight stays and 5,548,000 tourists) and confirm a recovery of activity within the framework of the post-pandemic scenario derived from COVID-19 [16]. The Costa Daurada and Terres de l'Ebre are two destinations that have their own and differentiated tourism strategy. Both destinations share a territorial space that is managed by the Diputación de Tarragona and in which it exercises its powers as a local administration.

Framework of Competencies and Functions

To properly understand competency frameworks, it is necessary to distinguish between a series of concepts that, despite being similar and often operating as synonyms, do not express exactly the same thing: competence, function, task and role. From this point of view, competence is understood as the function or set of public functions whose ownership is legally attributed to a public entity or one of its organs. Function is understood as the one carried out by an institution or entity, its organs or its people. Task is understood as the work that one has the obligation to carry out, which has been assigned to it. Finally, role is understood as the model of behavior that is expected of a person or organization. In other words, competence can be understood as what can and should be carried out, function as what is done, tasks as the actions that materialize a function and role as the way in which it operates.

In this research the focus is on competencies and functions.

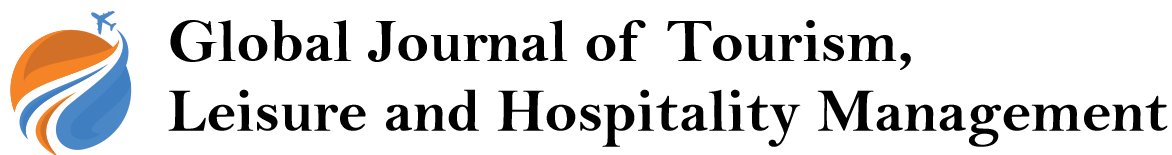

Competence framework of the provinces defined in LAW 13/2002, of June 21, on tourism in Catalonia.

As stated in its preamble, the Catalan tourism law responded to the new values inspiring the promotion and management of tourism, all of them expressed at the Catalan Tourism Congress held in Tarragona in February 2001, and included the international and community recommendations and directives on this matter. The Law takes into account the impact and economic opportunities that an activity of this type has on the progress and social development of the territory, without shirking the responsibility of preserving the natural, historical, cultural and environmental values of the resources that make this activity possible, in accordance with the principle of sustainable development. The Law places emphasis on tourist users, or tourists, and emphasizes their rights and the need for them to receive adequate treatment and quality services. It also recognizes the rights of companies or tourist subjects and, by dealing with the necessary collaboration between the private sector and tourist administrations, sets the possibilities and limits of the respective actions. In relation to this last point we find:

Article 71:

i. Without prejudice to the powers established by local government legislation, the following powers correspond to the Provincial Councils:

a) The promotion of tourism brands in its territorial scope.

b) The promotion of tourist resources within its territorial scope, in coordination with all local entities concerned.

c) Advice and technical support to local entities within its territorial scope in any aspect that improves their tourism competitiveness.

d) The articulation, coordination and promotion of promotional strategies derived from the private sphere of the tourism sector.

e) Participation in the formulation of tourism planning tools for the entire country.

ii. Provincial councils must exercise their tourism powers in coordination with the department responsible for tourism and with other tourism administrations within their territorial scope.

iii. For the purposes of proper coordination between the provincial councils and the Generalitat Administration, the formulas for reciprocal participation that are considered necessary in the specialized entities and organizations that depend on them must be established.

6.2. Competence framework defined in the statutes of the Tarragona Provincial Council's Tourism Board

The statutes of the PTDT are the document that defines its powers and establishes the conditions for its governance. The first document dates back to 1986 and has undergone four modifications in 1999, 2005, 2017 and 2019. The 2005 modification is essentially established to accommodate differentiated management by the Terres de l'Ebre brand. The 2017 and 2019 modifications are aimed at updating the material content of these to the legislative developments in the field of the legal regime of the public sector, to adapt the management of human resources to the new scenario derived from the process of functionalization of the PTDT staff and to harmonize the structure and content of the same with that of the other autonomous body of the Tarragona Provincial Council, BASE-Gestión de Ingresos, in order to simplify and facilitate its analysis while respecting the obvious singularities of each entity.

The changes in the wording of the functions have not been significant and have meant more of a semantic update than a substantial variation in tasks. In the latest version of 2019, article 3 includes the following functions:

a) To study the overall lines of tourism policy in the regions of Tarragona.

b) Promote the strengthening, promotion and commercialization of the different tourist resources of the Costa Daurada and the Terres de l'Ebre.

c) Activate and coordinate marketing actions aimed at increasing tourist demand and awareness of the Costa Daurada and Terres de l'Ebre brand.

d) Promote, produce and distribute the necessary advertising and/or informational tourist materials of interest to the regions and the different products.

e) Support, materially or technically, the initiatives and activities of entities with similar functions in smaller areas of action and ensure their coordination.

f) Coordinate the Autonomous Body with the regional and state administration.

g) Organise and develop campaigns and actions that, in addition to being oriented towards the functions of the Autonomous Body, serve as an effective platform both for obtaining the image of the different tourist offers of the Tarragona regions, as well as for the marketing by companies, groups of companies or any other associative formula, of their tourist products.

h) Stimulate, propose or carry out all types of actions and activities that, due to their content, promote tourism in their area of action.

i) To analyse the tourism problems of the Costa Daurada and Terres de l'Ebre, and consequently to propose and adopt the measures considered most appropriate to solve them.

j) Establish exchange relations with institutions linked to tourism activity, both national and international.

k) Promote and support the creation of public and private facilities that allow for cultural and recreational activities aimed at visitors.

l) Promote citizen education campaigns related to the sociocultural aspects of tourism and the reception of visitors.

m) Provide advice and technical support to local entities within its territorial scope in any aspect that improves tourism competitiveness.

n) Articulate, coordinate and encourage promotional strategies derived from the private sector of the tourism sector.

o) Participate in the formulation of tourism planning instruments for the country as a whole.

p) And all those that are necessary for the fulfillment of the functions of the Autonomous Body.

Results

Correspondence between competences and functions

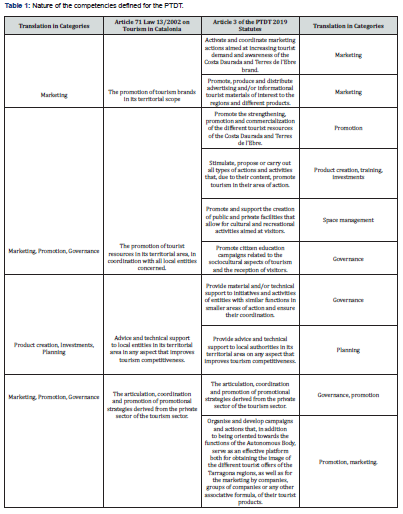

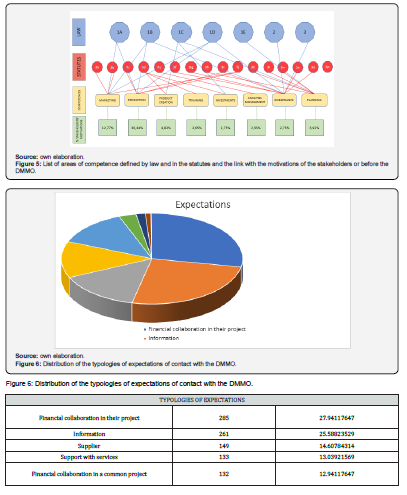

The comparison of the contents of article 71 of Law 13/2002 on tourism in Catalonia and article 3 of the PTDT statutes allows to find areas of coincidence, as well as to categorise the elements of each point in order to understand the nature of the defined competences (Table 1). The categories identified are: marketing, promotion, governance, product creation, investments, planning, training and management of spaces. It is observed that training and management of spaces are activities carried out by the PTD, which may be included in the competencies defined in the statutes of the PTDT but which have no correspondence in the law (Figure 1).

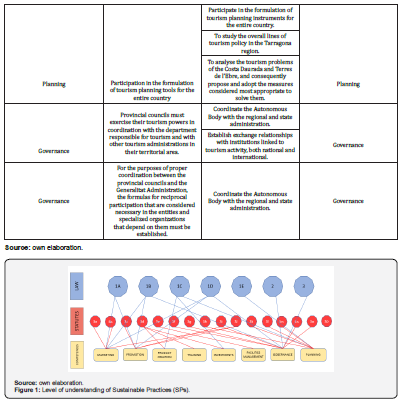

Results associated with the nature of the stakeholders

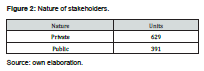

Analysis of meeting records shows that the actors who address the DMMO are mostly from the private sector (62%), which is understandable since their universe is much larger than that of the public sector actors (Figure 2).

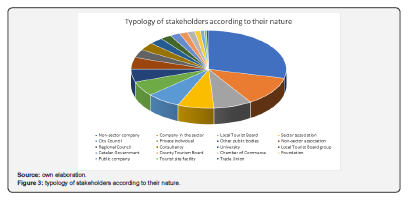

As regards the typology of stakeholders (Figure 3) within the public or private nature, a wide range is observed where companies, from the sector and outside it, are mostly the first groups to promote contacts with the DMMO. The weight of companies outside the sector is reinforced by the presence in this class of the group of suppliers who turn to the DMMO and who must be served by the public nature of the organisation and by the criteria of openness and transparency to which it is obliged. The associations of the sector show a notable value, but at the same time explain that they do not reflect all the representation of the sector.

Results associated with motivations and expectations

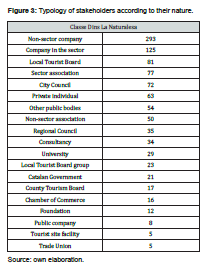

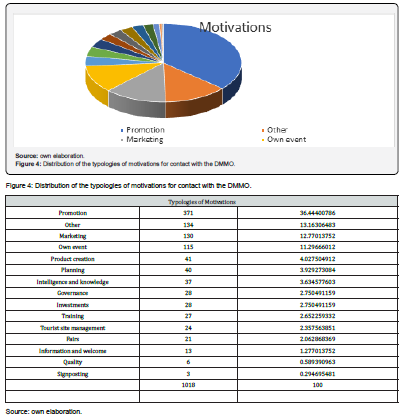

The analysis of the set of meetings held with stakeholders allows us to categorize a series of typologies of motivations that have led to requesting the meeting with the DMMO and that explain the nature of the topic to be discussed (Figure 4) allowing its association to a competence area:

Knowledge and intelligence: Actions whose objective is to organize, create, capture and distribute knowledge and ensure its availability to future people who will use it for management and greater competitiveness (3.63%).

Product creation: Process by which a tourist service is configured as a set of tangible and intangible components that includes tourist resources, services, equipment and infrastructure. Creation involves adding value for tourist consumption in order to satisfy the motivations and needs of visitors and tourists (4.02%).

Own event: Activity, of diverse nature (cultural, sports, gastronomic, corporate...), which is organized with the aim of encouraging a certain response to the call or a certain level of notoriety (11.29%).

Fairs: Events (economic, social, or cultural) that take place in a venue, which generally cover a common theme or purpose and which represent a space for meeting and interaction between a number of actors linked to the theme. The objective is often to stimulate sales. This category is different from the “promotion” blog due to its uniqueness (2.06%).

Training: Activities to transfer knowledge and mechanisms to improve skills to reinforce the abilities to interact with the environment with greater responsiveness (2.65%).

Facilities management: Actions related to the management of resources and spaces that are regularly visited for a few hours by tourists (2.35%).

Governance: Proposals associated with participation in governing bodies and links in the processes of exercising power to the entities responsible for managing the destinations (2.75%).

Information and welcome: Actions associated with the information activities of tourist offices and visitors welcome at the destination (1.27%).

Investments: Contacts generated to express the need for information that can be used to guide decision-making processes regarding potential investments or the adjustment of the scope of actions planned with the investments (2.75%)

Marketing: Particularly understood communication activities aimed at achieving objectives in the service of marketing: knowledge of the market, puttingg a product on sale and dissemination of promotional messages for the product to be marketed (12.77%)

Planning: Process to guide and promote more rational decision-making and a greater understanding of the tourism phenomenon, which aims to decide on the allocation of scarce resources in the achievement of multiple objectives through the appropriate means to obtain them (3.92%)

Promotion: Understood as marketing support activities that go beyond advertising and are common in the tourism sector: family trips, press trips, workshops, presentations. (36.44%)

Quality: Mechanisms that accredit the competence of an organization to offer services within the rules and standards pre-established by a regulatory body (0.58%)

Signaling: Orientation signage intended to guide users towards a destination of special tourist or cultural importance (0.29%)

Others: Elements other than the above and not categorizable (13.16%)

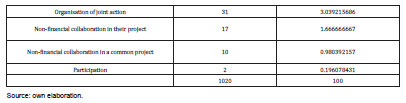

By identifying the motivations that can be associated with the areas of competence, it is possible to evaluate their weight and therefore recognize, beyond the regulatory framework, their impact on the real activity of the DMMO (Figure 5). Marketing and promotion competencies are, by far, those that generate the most contact with stakeholders. The analysis of the meetings with the stakeholders allows us to categorize a series of response typologies that are expected to be received as a result of the meeting and that explain the expectations of the result on the part of the actors who have requested the meeting (Figure 6).

Support with services: Help is expected through the deployment of activities that are specific to the destination management entity (13.03%).

Financial support for their project: Financial support is expected for the proposal that has been presented and is organized or led by the stakeholder (27.94%).

Financial collaboration in a common project: Financial support is expected for an activity led by the destination management body and which involves financial expenditure (12.94%).

Non-financial collaboration in a common project: Support is expected to be received for an activity led by the destination management body and which does not entail any financial expense (0.98%).

. Non-financial collaboration in their project: Help is expected through the deployment of activities that are not usual for the destination management entity (1.66%).

Information: It is expected to provide or receive knowledge, details or clarifications on a topic. (25.58%).

Joint action organization: It is expected that an activity will be developed jointly, making its leadership also shared (3.03%).

Stake: It is expected to be able to be linked in one way or another to the governing bodies of the destination management entity (0.19%).

. Supplier: It is expected to establish a relationship as a supplier to the destination management entity (14.60%).

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

The interaction between destination management bodies (DMMOs) and stakeholders is revealed as a key aspect to understand the complexity of regional tourism management. This study illustrates how dialogue with stakeholders can significantly influence the functions and responsibilities of a DMMO, as has been observed in other research [5,12]. The functions formally assigned through legislation and statutes are only an initial framework that must be adapted and modulated in response to the dynamics of the actors involved. The dominance of private actors in setting the DMMO agenda highlights a trend towards prioritising business needs, a phenomenon that Morrison et al. [5] identify as a response to pressures for economic development. However, this may entail risks of subordinating sustainability to operational efficiency, suggesting the need to rebalance policies towards more sustainable management.

The focus on marketing and promotion, as the main areas of interaction with stakeholders, confirms [3] theory on the need for adaptive roles by DMMOs in response to the life cycles of tourism products. This approach, while supporting economic development, could limit DMMOs' ability to address key aspects such as long-term planning and social inclusion. Indeed, sustainability management and social harmony might require greater attention, as [7] suggests in her approach to sustainable competitiveness of destinations. Similarly, [4] identify this dichotomy between marketing and the rest of the functions and recommend finding an optimal balance between them, although other authors highlight the fact that there is already a trend towards management beyond marketing Gretzel et al. [17].

The absence of certain voices in interactions with DMMOs, coupled with a tendency to respond reactively to short-term needs, poses a significant challenge. As Sheehan et al. [11] argue, managing perceptions and relationships with all stakeholders is vital for the legitimation and effectiveness of DMMOs [18]. It is critical for these organizations to expand their interaction to include a greater diversity of stakeholders and ensure that tourism management strategies reflect a deep understanding of all perspectives involved. The predominantly reactive approach of DMMOs could benefit from a shift towards more proactive and integrated practices, to improve governance in complex socio-political systems such as those surrounding tourism destination management [19]. This transition towards a more inclusive and sustainable governance model can help ensure that destinations not only thrive economically, but also maintain their long-term social and environmental viability [20].

Conclusion

This study has highlighted the complex dynamics between the competences normatively defined for DMMOs and the real needs expressed by stakeholders, highlighting a notable predominance of marketing and promotion activities, which represent more than 50% of interactions with destination stakeholders [21]. This approach contrasts with the lesser attention received by crucial areas such as strategic planning, governance - highly included in the statutes and the tourism law, training, space management and product creation, which are essential for sustainable and equitable management of tourist destinations. The range of competences that can be normatively developed is certainly wide but the focus of stakeholders is mainly concentrated in the area of marketing and promotion. There is a greater presence of private actors (62%) than public ones (38%), although it must be understood that the universe of the former is greater than that of the latter and therefore this imbalance is understandable. It would be interesting to further analyze this point in order to identify whether a clear sensitivity of the DMMO to market dynamics also reinforces this majority volume. The actors express more individual concerns than collective ones. This aspect is reinforced by the fact that the number of contacts generated by individual companies is often higher than that channelled through associations.

Furthermore, the topics addressed at the meetings tend to be more tactical than strategic, with a short-term focus that could limit the ability of destinations to adapt and innovate in the face of long-term changes in the tourism sector. This trend reinforces the interpretation that the functions of the DMMO are not fully aligned with the regulatory frameworks that govern them, giving rise to a certain dysfunctionality in their operations. There is a lack of proposals that invite a new direction of the activity of the regional DMMO, even if they were tacit. Most of the proposals seek material support in various forms. The regional DMMO is seen by many as a source of funding when analysing the expectations of the meetings. Among the expectations, a certain importance of the “information” class is detected (25.58%), an element that can be interpreted as an indicator of the entity's leadership capacity vis-à-vis the actors of the destination. It is identified that the intensity or frequency of the encounters is more defined by personal patterns of action of those who address the entity rather than by the potential of what they represent. One element that could lead to further work would be to analyse those missing in interactions with the DMMO to determine who is not being represented and why. This could help develop more inclusive strategies that ensure all voices are heard in the management of tourist destinations, enhancing their long-term sustainability and resilience.

References

- Fyall A, Oakley B, Weiss A (2000) Theoretical perspectives applied to inter-organisational collaboration on Britain's inland waterways. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration 1 (1): 89-112.

- De Araujo LM, Bramwell B (2002). Partnership and regional tourism in Brazil. Annals of tourism research 29 (4): 1138-1164.

- Choy DJ (1993) Alternative roles of national tourism organizations. Tourism Management 14 (5): 357-365.

- Gartrell R (1994) Strategic Partnerships. In Destination Marketing for Convention and Visitor Bureaus (2nd edition). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co, pp. 230-232.

- Bieger T, Beritelli P, Laesser C (2009) Size matters! -Increasing DMO effectiveness and extending tourist destination boundaries. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal 57(3): 309-327.

- Morrison A, Bruen S, Anderson D (1998) Convention and visitor bureaus in the USA: a profile of bureaus, bureau executives, and budgets. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 7 (1): 1-19.

- Jørgensen MT (2016) Developing a holistic framework for analysis of destination management and/or marketing organizations: six Danish destinations. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 34 (5): 624-635.

- Valero-Quezada AM (2021) The role of destination management organizations and the sustainable competitiveness of tourist destinations: the case of Mexico. Nova Rua 13 (23): 135-159.

- Mitchell RK, Agle BR, Wood DJ (1997) Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of management review 22 (4): 853-886.

- Kooiman J (1993) Governance and governability: using complexity, dynamics, and diversity. In Modern governance: New Government-Society Interactions.

- Sheehan LR, Ritchie JRB (2005) Destination stakeholders exploring identity and salience. Annals of tourism research 32 (3): 711-734.

- Sheehan LR, Ritchie JRB, Hudson S (2007) The Destination Promotion Triad: Understanding Asymmetric Stakeholder Interdependencies Among the City, Hotels, and DMO. Journal of travel research 46 (1): 64-74.

- Hyden G Court J Mease K (2003) Making sense of Governance: The Need for involving Local Stakeholders. Overseas Development Institute. Discussion paper.

- Beritelli P, Laesser C (2011) Power dimensions and influence reputation in tourist destinations: Empirical evidence from a network of actors and stakeholders. Tourism Management 32 (6): 1299-1309.

- Scott J (1990) A Matter of Record: Documentary Sources in Social Research. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Ahmed JU (2010) Documentary research method: New dimensions. Indus Journal of Management & Social Sciences 4 (1): 1-14.

- Patronat of Tourism of the Provincial Council of Tarragona (2024) Action Plan.

- Gretzel U, Fesenmaier DR, Formica S, O'Leary JT (2006) Searching for the future: Challenges faced by destination marketing organizations. Journal of Travel Research 45 (2): 116-126.

- Bornhorst T, Ritchie JRB, Sheehan L (2010) Determinants of tourism success for DMOs & destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders' perspectives. Tourism Management 31 (5): 572-589.

- Legislative Decree (2003) approving the consolidated text of the Municipal Law and the local regime of Catalonia.

- Statutes of the Tourist Board of the Provincial Council of Taraagona (2005).

- Pearce DG (1992) Tourist organizations. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, USA.