Unintentional Acute Carbon Monoxide Poisoning During Pregnancy: Five Years of Experience in Bordeaux

Rajaonarison JJC1, Nithart A2, Rakotomahenina H3, Randaoharison PG1, Dallay D2 and Sentilhes L2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital of Mahajanga, Madagascar

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital of Bordeaux, France

3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital of Fianarantsoa, Madagascar

Submission: July 17, 2018;Published: September 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Jose Rajaonarison, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital of Mahajanga, Mahajanga, Madagascar.

How to cite this article: Rajaonarison JJC, Nithart A, Rakotomahenina H, Randaoharison PG, Dallay D,et al. Unintentional Acute Carbon Monoxide Poisoning During Pregnancy: Five Years of Experience in Bordeaux. Glob J Reprod Med. 2018; 6(1): 555679. DOI: 10.19080/GJORM.2018.06.555679.

Abstract

Introduction: The objective of the study was to assess cases of maternal and fetal prognosis of carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning during pregnancy at the UHC of Bordeaux.

Materials and method: A retrospective and descriptive study based on observation of cases of carbon monoxide poisoning in pregnant women was conducted at the University Hospital Centre of Bordeaux which review was completed, from 01/01/2011 to 30/06/2016.

Results: The incidence on 24 pregnant women of carbon monoxide poisoning upon the 248 cases reported at the centre was compiled making a rate of 9,67%. Eleven of them were fully monitored. Two patients out of the eleven were tobacco smokers. CO poisoning originated either from: fire (6/11), faulty heating appliances (4/11) or electric short circuit (1/11). Two of the seven patients presenting a COHb level in the blood had an amount of >10%. One patient had suffered with a right bundle block. Eight women out of the eleven were treated with oxygen therapy using face mask on their way to hospital. The centre systematically uses hyperbaric oxygen therapy, which dose and duration vary depending on the case and on the practitioner. Two foetus were affected with in utero growth restriction, and another one with a perinatal asphyxia. Two premature births were admitted to prenatal resuscitation. All along this investigation, no prenatal death were linked to carbon monoxide poisoning.

Conclusion: Complications on the foetus resulting from that hazard are serious and unpredictable. A high rate normobaric oxygen therapy with oro-nasal mask is recommended while awaiting the hyperbaric oxygen which therapy must be systematically administered during pregnancy. Obstetrical management is considered case-by-case.

Keywords: Neonatal asphyxia; Carbon monoxide poisoning; Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Abbrevations: CO: Carbon Monoxide; UCAIM: Unit of Coordination and Analysis of Medical information; UHC: University Hospital Centre; ECG: Electrocardiogram; NBO: Normobaric Oxygen; HBO: Hyperbaric Oxygen

Introduction

Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is a common intoxication found in France. It causes serious outcomes on population with a mortality rate of 0,31/100000 in some areas of France [1], a sudden lethality for 1,26% [2], and neurological sequelae that might be severe. In France, 5,4% of victims are pregnant women [3]. The rate of fetal mortality due to CO poisoning during a pregnancy can reach 19 to 24% [4]. The physiopathological suggestions had proved that a foetus is more susceptible regarding of intensity and duration of exposure than a mother. Although various studies had brought light on how to understand physiopathologies, diagnosis, therapy principle; the frequency of neurological sequelae, pronostic factors, the fetal prognosis of a CO exposure during pregnancy and the monitoring system of victims remain in shade. Practices diverge on how to prescribe an hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

The following study aims to describe maternal and fetal complications of CO poisoning during pregnancy. From the obtained results, the prescription of an HBO therapy, maternal sequelae and fetal prognosis will be discussed.

Materials and Method

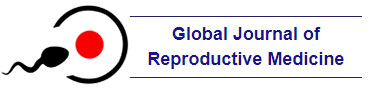

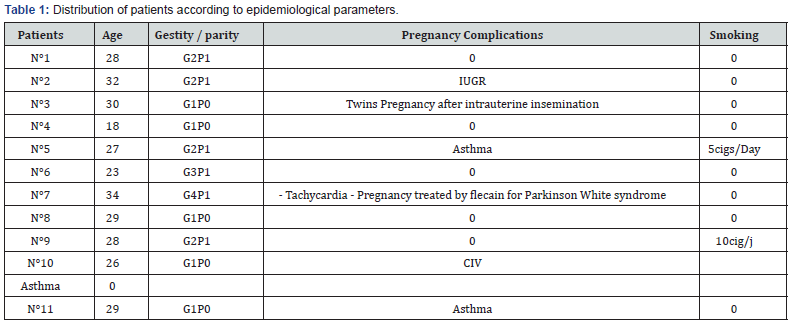

A retrospective and descriptive study based on observation of patients was conducted. Women poisoned with carbon monoxide and admitted to hospital were included in the study. A list of patients was retrieved from the UCAIM (Unit of Coordination and Analysis of Medical information) data at the UHC (University Hospital Centre) of Bordeaux over 5 years and 6 months (from 01/01/2011 to 30/06/2016). Patients who did not deliver in Bordeaux or not having a filed telephone number were excluded from the investigation. Other patients who had delivered in other centres were contacted by phone calls to get informed on the evolution of the pregnancy and its outcomes. For each patient, the background of the poisoning was investigated (cause, duration of exposure, ambient concentration of CO), together with clinical and paraclinical manifestations, management (normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen therapies), the evolution of the pregnancy and all possible sequelae (Table 1-2).

IUGR: Intra uterine growth retardation; IAC: husband’s sperm insemination; CIV: inter-ventricular communication.

ppm: part per thousand.

Results

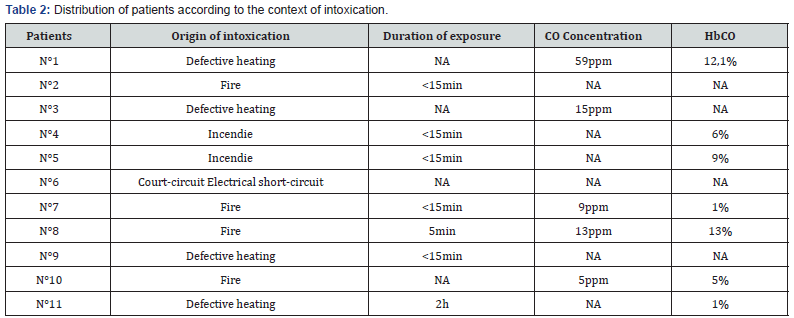

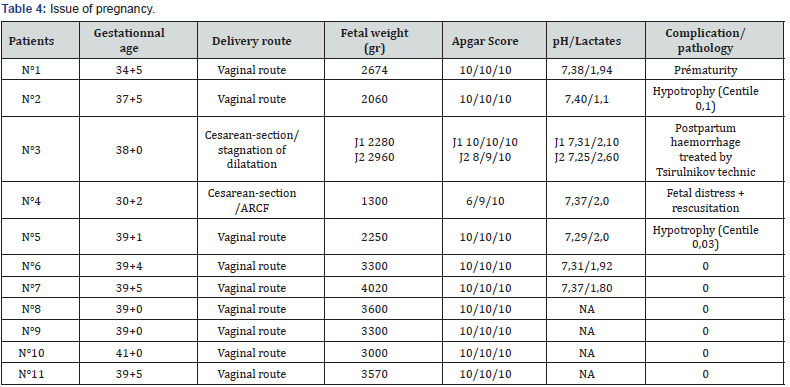

Data from the twenty four pregnant women were collected upon 248 cases of CO poisoning treated at the centre giving a rate of 9,67%. Eleven of them were completely monitored, the remaining (13cases) were not included in the study. The epidemiologies and features of the poisoning were respectively shown in table I and II. Eight women were asymptomatic and four others presented neurological symptoms as (headaches, dizziness, malaise, mild loss of consciousness, asthenia). Two of them have shown one with digestive signs (nausea, vomiting) and the other with asthenia. Obstetrical manifestations were illustrate on table III. An Electrocardiogram (ECG) performed on ten patients revealed that one of them had presented a right bundle block. Eight patients out of the eleven were treated with face fitted masked normobaric oxygen (NBO) at a flow rate of 15L/min before admission to hospital. The average time elapsed between the intoxication and the onset of an hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) treatment is of 11,75h with margins of 4 to 48h. The pressure used was of 1,5ATA (Atmosphere absolute) (9/11) and 2,5ATA (2/11). The duration of the HBO treatment depends on medical practitioners and according to the seriousness of cases; ranging from 115 min for 8 patients, 150min for two others and 190min for the last one. Perinatal complications were given on table IV. Within a period of 1 to 5 years one child out of 11 had two conditions of bronchiolitis before the age of two years (Table 3&4).

SA: Gestationnal age; MAF: actif fetal movement; ARCF: abnormal antenatal fetal heart rate records

ARCF: abnormal antenatal fetal heart rate records, HPPI: Immediate postpartum haemorrhage.

Discussion

Carbon monoxide poisoning is the most familiar intoxication in France. The InVs (Institute of Health Surveillance) records 4000 cases per year but its incidence is underestimated for several reasons: reporting is not obligatory, intoxications from smokes are excluded from the declared case, and finally, since that gas is odourless and colorless and symptoms do not always appear, some cases of CO poisoning are often misdiagnosed [5]. In 2012, that condition was a very common hazard during pregnancy with a rate of 9,67% in Bordeaux [6], 8,5% [7], in United States and less frequent in northern France (5,4%) [3]. Among the reported causes were: fire, and faulty heating appliances which promote the spate of occurence during wintry season [8]. Practically, managing CO poisoning encounters issue in diagnosis. Its definition varies from one centre to another, ambient concentration is changing, and the duration of exposure is often unknown [6,9]. Clinical signs depend on the atmospheric concentration at the intoxication. In a range of 100-200ppm, headaches, nausea/vomitings, dizziness, asthenia and malaise appear. Within 300-500ppm, the patient may present polypnea, dyspnea, tachycardia, chest pains, and slight loss of consciousness. At 1000ppm, a convulsion, or a coma may take place. Between 2000-5000ppm death occurs in few minutes [10].

Minor disorders are noticed within 30 to 40% of cases [11], and more serious neurological manifestations occur in 1 to 4% [12]. During pregnancy, the most common signs are the reduction of the active fetal movement (3cases in this series), threat of a premature delivery (1case) but the poisoning may also be without symptoms. On a paraclinical basis, an Electrocardiogram displayed a common epicardial or endocardial ischemia [9]. In this series one case of bundle block was recorded. The plasmatic level of COHb correlates with the time elapsed after the hazard. Four patients were reported without that level. It was also the case of another study conducted at the same region in 2012, by Bernadet P and al. [6] all 76/252 cases were reported without the dosage. For a therapy management, a systematic treatment using NBO must be performed.

It was one of the basic therapy that is achieved at high flow rate (12-15L/min) using a face mask, and which should immediately be started at the premices of the accident. A regular check of the fetal heart beat is practiced for 1h [13], and the oxygen therapy must be continued for 16h or more if no improvement is observed or the hyperbaric oxygen is not available [14]. Eight patients out of the eleven had followed this treatment. Applying hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) fastens the dissociation of COHb molecules, reduces its elimination half-life, rise the plasmatic concentration of oxygen and prevent formation of free radicals [15,16]. Its prescription during pregnancy is beneficial since it contributes to reduce the severity of the fetal injuries, the occurence of malformations and it was proved to be safe [17,18]. According to some authors, no significant difference of effectiveness is noticed when compared with a NBO therapy [19]. In literature the pressure used is usually of 2ATA for 120 min or 2,5 ATA for 90min [15].

Silverman RK, et al. [20] recommended another administration when maternal or fetal symptoms remain 12h after the first application. In Bordeaux, such session is systematically performed during pregnancy not regarding the severity of the intoxication. Oxygen pressure of 1,5ATA (9/11) for 115min is commonly used (8/11). A long record of the fetal heart beat is obligatory with a management of possible risk of premature delivery. One case was handled all along this study. A fetal hypoxia requiring an emergency caesarian section in one of the pregnant patient was the most frequent complication of this condition. It came out of a maternal hypoxia thanks to a high affinity of CO with the fetal haemoglobin, the delay of its elimination, and the misuse of oxygen by cells [3,4]. At a beginning of a pregnancy, malformations like microcephaly, dysgenesis of the telencephalon may occur within a second quaterly of brain injuries at the basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum and the spinal cord [15,21,22]. It resulted in hypotonia or even a cerebral palsy after delivery [23,24].

The absence of other causes of IUGR which involved two cases of this series allow us to realize that such growth restriction would come from the poisoning. Such complication had not yet been reported in literature. Moreover, the occurrence on one of the patient of a subchorionic hematoma could not be otherwise explained. Perinatal mortality associated to this intoxication can reach up to 36-67%. On the long run, no infant pathology was linked to a CO poisoning. The cases of broncholitis found on a child were not necessarily related to in utero CO exposure. As for maternal death, figure could attain 1,26% of the intoxicated. The prognosis is not different from that of non-pregnant women. No maternal death related to the poisoning was recorded during the study, however literature reported cases of adult losses during pregnancy [22]. Severe manifestations occurred in 1 to 4% of cases [12,25,26], leaving survivors with sequelae mainly depression, anxiety, or impaired cognitive ability resulting in disturbances at work [27].

The presence of a cardiac comorbidity (one woman has a VSD in this series), an abnormality of the Electrocardiogram (one case of right bundle block found on one patient) and various forms of poisoning (smokes from fire on 6 of the pregnant women) are part of the pronostic factors of the maternal mortality [28]. Neurological sequelae are feared when a loss of consciousness or an initial cerebellar syndrom [18,29], headaches, fainting or dizziness occurred, or failing a HBO therapy particularly when the blood level of COHb is >25% [15,30].

Conclusion

CO poisoning is not an exceptional condition at the centre of the study. A better management is obtained through a systematic oxygen therapy during pregnancy and it can improve the figure of prognosis. The French population still need to be informed of the risk of contracting home CO poisoning, its outcomes and management.

References

- L’état de santé de la population en France. Mortalité par intoxication par le monoxyde de carbone (CO).

- JM Yvon, D Casamatta (2015) Les intoxications au monoxyde de carbone en Rhône-Alpes. Données de surveillance 2013. Bulletin de veille sanitaire.

- Wattel F, Mathieu D, Neviere R, Mathieu-Nolf M, Lefebvre-Lebleu N (1996) Intoxication au monoxyde de carbone. Presse Med 25:1425- 1429.

- Elkharrat D, Raphael JC, Korach JM, Jars-Guincestre MC, Chastang C, et al. (1991) Acute carbon monoxide intoxication and hyperbaric oxygen in pregnancy. Intensive Care Med 17(5): 289‑292

- Friedman P, Guo XM, Stiller RJ, Laifer SA (2015) Carbon Monoxide Exposure During Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 70(11): 705‑712.

- Bernadet P, Gil-Jardiné C, Dondia D, Versmée G, Labadie M (2014) Implémentation des dossiers d’intoxication au monoxyde de carbone en 2012 en Aquitaine et Poitou Charentes. Toxicol Anal Clin 26(4): 212.

- Converse Peirce E, Kaufmann H, Bensky WH, Fischer B, Goldfrank L, et al. (1988) A registry for carbon monoxide poisoning in New York City. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 26(7): 419‑441.

- Carbon Monoxide Exposures---United States, 2000--2009. Weekly. 60(30): 1014‑1017.

- Raphael JC (2005) Recognizing and treating acute carbon monoxide poisonings in 2005. Réanimation 14(8): 716‑720.

- Aboab J, Hullin T, Annane D (2015) Intoxications oxycarbonées. Encycl Méd Chir - Pathologie professionnelle et de l’environnement 10(4):1‑8.

- Verrier A (2008) Les intoxications au monoxyde de carbone surnenues en France métropolitaine en 2006. Bull Epidemiol Hebd 44: 425-428.

- Mathieu D, Nolf M, Durocher A, Saulnier F, Frimat P, et al. (1985) Acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Risk of late sequelae and treatment by hyperbaric oxygen. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 23(4‑6): 315‑324.

- Towers CV, Corcoran VA (2009) Influence of carbon monoxide poisoning on the fetal heart monitor tracing: a report of 3 cases. J Reprod Med 54(3): 184‑188.

- Palmer J, Von Rueden K (2015) Carbon Monoxide Poisoning and Pregnancy: Critical Nursing Interventions. J Emerg Nurs 41(6): 479‑483.

- Bothuyne Queste E, Joriot S, Mathieu D, Mathieu-Nolf M, Favory R, et al. (2014) Ten practical issues concerning acute poisoning with carbon monoxide in pregnant women. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 43(4): 281‑287.

- Greingor JL, Tosi JM, Ruhlmann S, Aussedat M (2001) Acute carbon monoxide intoxication during pregnancy. One case report and review of literature. Emerg Med J 18(5): 399-401.

- Van Hoesen KB, Camporesi EM, Moon RE, Hage ML, Piantadosi CA (1989) Should Hyperbaric Oxygen Be Used to Treat the Pregnant Patient for Acute Carbon Monoxide Poisoning?A Case Report and Literature Review. JAMA 261(7):1039-1043.

- Weaver LK, Hopkins RO, Chan KJ, Churchill S, Elliott CG, et al. (2002) Hyperbaric Oxygen for Acute Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. N Engl J Med 347(14): 1057‑1067.

- Juurlink DN, Stanbrook MB, McGuigan MA (2000) Hyperbaric oxygen for carbon monoxide poisoning (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Oxford, USA.

- Silverman RK, Montano J (1997) Hyperbaric oxygen treatment during pregnancy in acute carbon monoxide poisoning. A case report. J Reprod Med 42(5): 309‑311.

- Abboud P, Mansour G, Lebrun JM, Zejli A, Bock S, et al. (2001) Acute carbon monoxide poisoning during pregnancy. Two cases with different neonatal outcome. J Gynécol Obstet Biol Reprod 30(7): 708-711.

- Gul A, Gungorduk K, Yildirim G, Gedikbasi A, Ceylan Y (2009) Prenatal diagnosis of porencephaly secondary to maternal carbon monoxide poisoning. Arch Gynecol Obstet 279(5): 697-700.

- Yildiz H, Aldemir E, Altuncu E, Celik M, Kavuncuoglu S (2010) A rare cause of perinatal asphyxia: maternal carbon monoxide poisoning. Arch Gynecol Obstet 281(2):251‑254.

- Marret S (2005) Effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on fetal brain development. J Gynecol Obst Biol Reprod 34 Spec No1: 3S230- 3S233.

- Raphaël JC, Elkharrat D, Jars-Guincestre MC, Chastang C, Chasles V, Vercken JB, et al. (1989) Trial of normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning intoxications. Lancet 2(8660): 414-419.

- Blettery B, Virot C, Janoray P, Piganiol G (1983) Acute carbon monoxide poisoning in the emergency service. The importance of early signs. 90 cases. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 133(2): 99-101.

- Borras L, Constant E, De Timary P, Hugquet P, Khazaal Y (2009) Longterm psychiatric consequences of carbon monoxide poisoning: a case report and literature review. Rev Med Interne 30(1): 43-48

- Kao HK, Lien TC, Kou YR, Wang JH (2009) Assessment of myocardial injury in the emergency department independently predicts the shortterm poor outcome in patients with severe carbon monoxide poisoning receiving mechanical ventilation and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 22(2009): 473-477.

- Weaver LK, Valentine KJ, Hopkins RO (2007) Carbon monoxide poisoning: risk factors for cognitive sequelae and the role of hyperbaric oxygen. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176(5): 491‑497.

- Annane D, Chevret S, Jars-Guincestre C, Chillet P, Elkharrat D, et al. (2001) Prognostic factors in unintentional mild carbon monoxide poisoning. Intensive Care Med 27(11): 1776‑1781.