Abstract

Superior Thyroid Cornu Syndrome (STCS) is an uncommon condition characterized by structural anomalies of the thyroid cartilage’s superior horn, leading to symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, throat pain, and globus sensation. This paper presents four clinical cases diagnosed with STCS and provides a comprehensive review of the literature, covering etiology, pathophysiology, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies. Increased clinical awareness of this rare entity is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate interventions.

Keywords:Superior thyroid cornu syndrome; Dysphagia; Globus sensation; Cartilage displacement; Case report; Endoscopy; CT scan

Abbreviations:STCS: Superior Thyroid Cornu Syndrome; LPR: laryngopharyngeal Reflux; Ho: YAG: Holmium: Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet; PPIs: Proton Pump Inhibitors; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Introduction

Superior thyroid cornu syndrome (STCS) is a rare condition characterized by abnormalities of the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage [1,2]. The thyroid cartilage, a key structure in the larynx, features two superior cornua (horns) that project upwards, providing attachment points for ligaments connecting to the hyoid bone. STCS arises when there are structural or positional irregularities in these cornua, leading to a constellation of symptoms that can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life. The rarity of this syndrome often results in delayed or incorrect diagnoses, making awareness and understanding of STCS crucial for clinicians. The abnormality in STCS often involves medial displacement or elongation of the superior cornu due to ossification [1]. This means that the superior horn of the thyroid cartilage is either shifted towards the midline of the neck or is longer than normal, or both. Ossification, the process of cartilage turning into bone, can further exacerbate these issues, making the cartilage more rigid and prone to causing irritation or compression of surrounding structures. The specific mechanisms driving medial displacement and elongation are not fully understood but are thought to involve a combination of congenital predispositions and acquired factors. This syndrome can be either congenital or acquired, leading to various symptoms [2]. Congenital STCS is present from birth, resulting from developmental anomalies in the formation of the thyroid cartilage. Acquired STCS, on the other hand, develops later in life due to trauma, inflammation, or other pathological processes. The distinction between congenital and acquired forms is important because it can influence the clinical presentation and management strategies. Regardless of the etiology, STCS can cause a range of symptoms that affect swallowing, speech, and overall comfort.

Case Series

Case 1

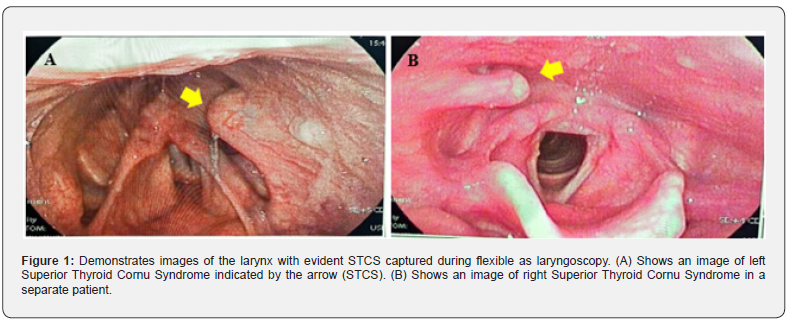

A 74 year old male patient presented to our clinic complaining of throat pain while swallowing and foreign body sensation in the neck. His symptoms started 2 months ago with negative history of neck trauma. On examination, the patient looked malnourished. He was a heavy smoker and reported a history of diabetes and hypertension. Full ENT examination was conducted, and it was unremarkable. Flexible endoscopy of the larynx showed a bulge in the left lateral pharyngeal wall above the left aryepiglottic fold, it had no malignant features and was Lined with macroscopically healthy mucosa (Figure 1). It was suggested that Superior thyroid cornu syndrome (STCS) could be the underlying cause of the condition.

Case 2

A 31 year old singer with no past medical history presented to our clinic complaining of dysphagia and foreign body sensation in the throat as well as throat discomfort. His symptoms started one month ago with negative history of neck trauma. On examination, the patient looked well. Full ENT examination was conducted, and it was unremarkable. Flexible endoscopy of the larynx a bulge in the right lateral pharyngeal wall above the right aryepiglottic fold, it had no malignant features and was Lined with macroscopically healthy mucosa (Figure 1). It was suggested that Superior thyroid cornu syndrome (STCS) could be the underlying cause of the condition.

Case 3

A 28 year-old male, smoker had symptoms suggestive of reflux laryngitis. Superior Thyroid Cornu syndrome on LT side was detected incidentally during flexible scope.

Case 4

A 46 year-old male with history of left T1 glottic squamous cell carcinoma, treated with radical radiotherapy 3 years ago. During routine surveillance, RT STCS was detected. CT neck was ordered and confirmed the diagnosis. All patients were informed about the benign nature of the condition and opted against surgical intervention. They were counseled to undergo regular annual follow-up to monitor symptom progression or complications.

Discussion

Superior thyroid cornu syndrome (STCS) is an abnormality of superior cornu of thyroid cartilage which can produce dysphagia, odynophagia or throat pain. The causes of this condition are congenital or acquired. STCS is a rare cause of chronic dysphagia or sore throat. Laryngologists should suspect it when malignancy of the larynx is ruled out. Ossification of superior thyroid cornu is a rare cause of symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, throat pain or foreign body sensation [1].

Common Symptoms and Manifestations

The main symptoms of superior thyroid cornu syndrome include cervical dysphagia, throat pain, and odynophagia [1,2]. Cervical dysphagia refers to difficulty swallowing that is specifically localized to the neck region, often described as a sensation of food getting stuck in the throat. Throat pain can manifest as a persistent soreness, ache, or sharp pain that is exacerbated by swallowing or speaking. Odynophagia, or painful swallowing, is another common symptom that can significantly impair a patient’s ability to eat and drink normally. These symptoms often overlap and can vary in severity depending on the degree of cartilage abnormality and individual patient factors. Patients with STCS may experience a persistent sensation of a lump in the throat, also known as globus sensation [3]. This feeling can be particularly bothersome and anxiety-provoking, as patients may worry about a potential tumor or other serious condition. Globus sensation in STCS is thought to arise from irritation of the pharyngeal mucosa or compression of surrounding structures by the displaced or elongated superior cornu. While globus sensation is a common symptom in various throat disorders, its presence in conjunction with dysphagia, throat pain, and odynophagia should raise suspicion for STCS.

Chronic cough has also been identified as a potential symptom of STCS, [4]. While less typical than dysphagia or throat pain, chronic cough can occur due to irritation of the laryngeal nerves or mucosa by the abnormal cartilage. The cough may be dry or productive and can be triggered by swallowing, speaking, or even changes in head position. The association between STCS and chronic cough highlights the importance of considering structural abnormalities of the larynx in the differential diagnosis of persistent cough, especially when other common causes have been ruled out. J. Lechien et al. reported a case of a 64-year-old female with a chronic cough due to a curved superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage and related irritation of the laryngeal superior nerve. The cough resolved after surgical resection of the abnormal cornu, with no recurrence at 9 months post-surgery [4].

Diagnostic Approaches

Diagnosis of superior thyroid cornu syndrome involves careful history taking and clinical examination [1]. A thorough medical history should include details about the onset, duration, and characteristics of symptoms, as well as any history of trauma, surgery, or other relevant medical conditions. Clinical examination typically involves palpation of the neck to assess for any masses or abnormalities, as well as assessment of laryngeal movement and vocal cord function. However, physical examination alone may not be sufficient to diagnose STCS, as the superior cornu is often deep and difficult to palpate directly. Flexible endoscopy and CT scans of the neck are crucial for confirming the diagnosis [1]. Flexible endoscopy, particularly nasolaryngoscopy, allows direct visualization of the larynx and pharynx, enabling the clinician to identify any structural abnormalities or signs of irritation. CT scans of the neck provide detailed anatomical information about the thyroid cartilage, including the position, size, and shape of the superior cornua. The combination of endoscopy and CT imaging provides a comprehensive assessment of the larynx and surrounding structures, facilitating accurate diagnosis of STCS. Nasolaryngoscopy can reveal a protruding mass through the pharyngeal wall [1]. This protruding mass corresponds to the medially displaced or elongated superior cornu, which may impinge on the pharyngeal mucosa. The overlying mucosa may appear normal or may show signs of inflammation or ulceration. In some cases, the protruding mass may be palpable during the endoscopic examination. Visualization of this mass during nasolaryngoscopy is a key diagnostic finding in STCS.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Congenital factors

Congenital abnormalities in the development of the thyroid cartilage can lead to STCS [2]. These developmental anomalies can manifest as variations in the size, shape, or position of the superior cornua, predisposing individuals to STCS. The exact mechanisms underlying these congenital abnormalities are not fully understood, but they are thought to involve genetic factors and disruptions in embryonic development. Understanding the congenital factors contributing to STCS is essential for identifying at-risk individuals and developing preventive strategies. These congenital variations may result in malformations or unusual positioning of the superior cornu [1]. Malformations can include elongation, thickening, or curvature of the superior cornu, while unusual positioning can involve medial displacement or abnormal angulation. These structural and positional abnormalities can cause irritation of surrounding tissues, compression of nearby structures, or mechanical obstruction of the pharynx, leading to the symptoms of STCS. The specific type and severity of the congenital variation will influence the clinical presentation and management approach. Further research is needed to fully understand the genetic factors contributing to these congenital issues. Genetic studies may identify specific genes or mutations that are associated with abnormal development of the thyroid cartilage. These findings could lead to the development of genetic screening tools to identify individuals at risk for congenital STCS. Additionally, understanding the genetic basis of STCS could provide insights into the underlying developmental processes and potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Acquired factors

Acquired STCS can result from trauma or idiopathic medialization [5]. Trauma to the neck, such as a direct blow or whiplash injury, can cause displacement or fracture of the superior cornu, leading to STCS. Idiopathic medialization refers to the gradual, spontaneous displacement of the superior cornu towards the midline, without any identifiable cause. The mechanisms underlying idiopathic medialization are not well understood, but they may involve age-related changes in cartilage structure or subtle, repetitive microtrauma. Pressure from surrounding structures, such as thyroid masses, can also displace the superior cornu. Enlarged thyroid nodules, cysts, or tumors can exert pressure on the thyroid cartilage, causing it to deform or shift out of its normal position. This is especially true if the mass is located near the superior cornu. Siti Farhana Abdul Razak et al. described a case of a patient with a medialized superior part of the thyroid cartilage caused by pressure from a large thyroid mass. The neck computed tomography scan revealed an elongated and medially displaced superior cornu of the right thyroid cartilage, resulting from the push exerted by the right thyroid mass [3]. Ossification and elongation of the cartilage can occur over time, leading to symptoms [1]. Cartilage, which is normally flexible, can undergo ossification, becoming more rigid and bone-like. This process can be accelerated by age, inflammation, or other pathological conditions. As the cartilage ossifies and elongates, it can impinge on surrounding structures, causing irritation, compression, and pain. The gradual nature of this process may explain why some patients with STCS experience a slow, progressive onset of symptoms.

Pathophysiological mechanisms

Medial displacement or elongation of the superior cornu can irritate adjacent structures in the throat [5]. The superior cornu is located in close proximity to the pharyngeal mucosa, laryngeal nerves, and blood vessels. When the cornu is displaced or elongated, it can rub against these structures, causing mechanical irritation and inflammation. This irritation is thought to be a primary driver of the symptoms of STCS. This irritation can cause inflammation, leading to throat pain, dysphagia, and odynophagia [1,2]. Inflammation of the pharyngeal mucosa can cause a burning or scratchy sensation in the throat, as well as increased sensitivity to touch. Inflammation of the laryngeal nerves can lead to pain that radiates to the ear or neck. Dysphagia and odynophagia can result from a combination of mechanical obstruction and inflammation, making it difficult and painful to swallow.

In some cases, the displaced cornu can impinge on the carotid artery, leading to clicking larynx syndrome and stroke [6]. The carotid artery, a major blood vessel that supplies blood to the brain, runs close to the thyroid cartilage. If the superior cornu is significantly displaced, it can compress or irritate the carotid artery, leading to turbulent blood flow and the formation of blood clots. These clots can then travel to the brain, causing a stroke. Catherine Y Han et al. presented a case of a patient with clicking larynx syndrome and a recent history of ischemic stroke [6]. Diagnostic imaging revealed unusual development and posterior angulation of the superior horn of the thyroid cartilage that potentially was causing trauma to the left common carotid artery [6].

Clinical Presentation and Symptomatology

Dysphagia and odynophagia

Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, is a primary symptom of STCS due to the mechanical obstruction caused by the displaced cornu [1,2]. The displaced or elongated superior cornu can narrow the pharyngeal space, making it difficult for food and liquids to pass through. Patients may describe a sensation of food getting stuck in their throat, requiring them to swallow repeatedly or modify their diet to softer foods. The severity of dysphagia can range from mild discomfort to complete inability to swallow, depending on the degree of obstruction.

Odynophagia, or painful swallowing, often accompanies dysphagia, exacerbating discomfort during eating [1]. The displaced cornu can irritate the pharyngeal mucosa, causing pain that is triggered by swallowing. Patients may describe a sharp, stabbing, or burning pain that radiates to the ear or neck. Odynophagia can lead to decreased appetite, weight loss, and malnutrition, especially if it is severe and persistent. The severity of dysphagia and odynophagia can vary based on the degree of displacement and individual anatomy [2]. Patients with more severe displacement of the superior cornu are more likely to experience significant dysphagia and odynophagia. Additionally, individual anatomical variations, such as the size and shape of the pharynx, can influence the severity of symptoms. A thorough clinical evaluation, including endoscopy and imaging, is essential for assessing the degree of displacement and individual anatomy in each patient.

Throat pain and globus sensation

Throat pain is a common complaint, often described as a persistent soreness or ache [1,2]. The pain may be localized to the area around the thyroid cartilage or may radiate to the ear, neck, or jaw. It can be exacerbated by swallowing, speaking, or changes in head position. The underlying cause of throat pain in STCS is thought to be irritation and inflammation of the pharyngeal mucosa and laryngeal nerves. Globus sensation, the feeling of a lump in the throat, can be particularly bothersome for patients [3]. This sensation is often described as a feeling of fullness, tightness, or pressure in the throat, without any actual physical obstruction. Globus sensation in STCS is thought to arise from irritation of the pharyngeal muscles or mucosa, as well as psychological factors such as anxiety and stress. While globus sensation is a common symptom in many throat disorders, its presence in conjunction with other symptoms of STCS should raise suspicion for this syndrome. These symptoms can significantly impact the patient’s quality of life, leading to anxiety and discomfort [3]. Chronic throat pain and globus sensation can interfere with daily activities, such as eating, speaking, and socializing. Patients may experience anxiety, depression, and social isolation as a result of their symptoms. Effective management of STCS requires not only addressing the underlying anatomical abnormality but also providing psychological support and counselling to help patients cope with their symptoms.

Associated symptoms

Chronic cough may present as a less typical symptom of STCS [4,5]. The cough may be dry or productive and can be triggered by swallowing, speaking, or changes in head position. The underlying cause of chronic cough in STCS is thought to be irritation of the laryngeal nerves or mucosa by the displaced cornu. In some cases, the cough may be the predominant symptom, leading to a delayed or incorrect diagnosis of STCS. Cervicalgia, or neck pain, can also occur due to the structural abnormalities [5]. The displaced cornu can put pressure on the surrounding muscles and ligaments, causing pain and stiffness in the neck. Cervicalgia may be exacerbated by certain head movements or postures. It can also contribute to headaches and shoulder pain. Clicking larynx syndrome, though rare, can be associated with STCS, especially when the displaced cornu impinges on surrounding structures [6]. Clicking larynx syndrome is characterized by a clicking or popping sound that is produced when the thyroid cartilage rubs against the hyoid bone or cervical spine. In STCS, the displaced cornu may make the thyroid cartilage more prone to rubbing against these structures, leading to clicking larynx syndrome. This syndrome can be painful and distressing for patients, and it may be associated with other symptoms such as dysphagia and throat pain.

Diagnostic Modalities and Evaluation

Flexible endoscopy

Flexible endoscopy, particularly nasolaryngoscopy, allows direct visualization of the larynx and pharynx [1]. This procedure involves inserting a thin, flexible scope through the nose and into the throat, allowing the clinician to examine the structures of the larynx and pharynx in real-time. Nasolaryngoscopy is a minimally invasive procedure that can be performed in the office setting with minimal discomfort to the patient. It provides valuable information about the anatomy and function of the larynx and pharynx, helping to identify any abnormalities or signs of inflammation. This procedure can reveal protruding mass or other abnormalities in the pharyngeal wall [1]. The protruding mass corresponds to the medially displaced or elongated superior cornu, which may impinge on the pharyngeal mucosa. Other abnormalities that may be seen during endoscopy include inflammation, ulceration, or swelling of the pharyngeal mucosa. The presence of these abnormalities, in conjunction with the patient’s symptoms, can help to confirm the diagnosis of STCS. Endoscopy helps rule out other potential causes of throat pain and dysphagia, such as malignancy [1]. It allows the clinician to visualize the larynx and pharynx, excluding any tumors or other lesions that may be causing the patient’s symptoms. If any suspicious lesions are identified during endoscopy, a biopsy can be performed to obtain tissue samples for further analysis. Ruling out malignancy is an important step in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with throat pain and dysphagia.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

CT scans of the neck are essential for confirming the diagnosis of STCS [1]. CT imaging provides detailed anatomical information about the thyroid cartilage, including the position, size, and shape of the superior cornua. The CT scan can clearly show the medially displaced or elongated superior cornu, as well as any other structural abnormalities of the larynx and surrounding tissues. The information obtained from the CT scan is crucial for planning surgical treatment and assessing the risk of complications. CT imaging can clearly show the elongated or medially displaced superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage [3]. The CT scan can also show the degree of ossification of the cartilage, which can influence the severity of symptoms. By measuring the length and position of the superior cornu, the clinician can determine the extent of the abnormality and its potential impact on surrounding structures. The CT scan provides a three-dimensional view of the larynx, allowing for accurate assessment of the anatomical relationships between the superior cornu and other structures in the neck. It also helps in assessing the extent of ossification and any associated structural abnormalities [2]. The CT scan can differentiate between cartilage and bone, allowing the clinician to assess the degree of ossification of the superior cornu. Ossification can make the cartilage more rigid and prone to causing irritation and compression. The CT scan can also identify any other structural abnormalities of the larynx, such as cysts, tumors, or fractures, which may be contributing to the patient’s symptoms.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to rule out other conditions that may mimic STCS, such as chronic pharyngitis or laryngopharyngeal reflux [7]. Chronic pharyngitis is a common condition characterized by inflammation of the pharynx, causing throat pain, scratchiness, and cough. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is a condition in which stomach acid flows back into the larynx and pharynx, causing irritation and inflammation. Both chronic pharyngitis and LPR can cause symptoms that are similar to those of STCS, making it important to consider these conditions in the differential diagnosis. Malignancies of the larynx should be excluded through thorough examination and, if necessary, biopsy [2]. Laryngeal cancer can cause throat pain, dysphagia, and hoarseness, which are also symptoms of STCS. A thorough examination of the larynx, including endoscopy and imaging, is essential for ruling out malignancy. If any suspicious lesions are identified, a biopsy should be performed to obtain tissue samples for further analysis. Other structural abnormalities, such as hyoid bone syndrome, should also be considered [8]. Hyoid bone syndrome is a condition characterized by pain and clicking in the neck, caused by instability or inflammation of the hyoid bone. The symptoms of hyoid bone syndrome can overlap with those of STCS, making it important to consider this condition in the differential diagnosis. Imaging studies, such as CT or MRI, can help to differentiate between STCS and hyoid bone syndrome.

Surgical Management Techniques

Transcervical approach

The transcervical approach involves surgical excision of the elongated or medially displaced superior cornu through an incision in the neck [1]. This is a traditional surgical technique for treating STCS. The procedure is performed under general anesthesia and typically takes one to two hours to complete. The surgeon makes an incision in the neck, usually along a skin crease, to minimize scarring. The muscles and tissues of the neck are carefully dissected to expose the thyroid cartilage and superior cornu. This method allows direct access to the affected cartilage for precise removal [1]. The surgeon can directly visualize and manipulate the superior cornu, ensuring that it is completely removed without damaging surrounding structures. The transcervical approach provides excellent control and precision, allowing for safe and effective removal of the abnormal cartilage. Post-operative contrast swallow studies and laryngoscopy can confirm the resolution of the syndrome [1]. After the surgery, a contrast swallow study may be performed to assess swallowing function and rule out any leaks or strictures. Laryngoscopy may also be performed to visualize the larynx and confirm that the superior cornu has been completely removed and that there are no other abnormalities. These post-operative studies help to ensure that the surgery has been successful and that the patient is recovering properly.

Transoral laser resection

Transoral resection using a holmium: yttrium-aluminumgarnet (Ho:YAG) laser is a novel approach for treating STCS [3]. This is a minimally invasive surgical technique that involves using a laser to vaporize or cut away the abnormal cartilage. The procedure is performed through the mouth, without the need for any external incisions. The Ho:YAG laser is a type of laser that emits light at a specific wavelength that is highly absorbed by water, making it ideal for cutting and vaporizing soft tissues. This technique offers greater precision and reduces the risk of soft tissue trauma compared to traditional methods [3]. The laser can be precisely targeted to the abnormal cartilage, minimizing damage to surrounding tissues. The transoral approach avoids the need for external incisions, reducing the risk of scarring and infection. Patients who undergo transoral laser resection typically experience less pain and a faster recovery compared to those who undergo traditional transcervical surgery.

Considerations for surgical planning

Careful pre-operative planning is crucial to determine the optimal surgical approach [1]. The surgeon must carefully evaluate the patient’s symptoms, medical history, and imaging studies to determine the best way to approach the surgery. Factors to consider include the size and location of the superior cornu, the degree of ossification, and the presence of any other abnormalities. The surgeon must also consider the patient’s overall health and any other Surgeons must be aware of the proximity of vital structures, such as the carotid artery and laryngeal nerves, to avoid complications [6]. The carotid artery and laryngeal nerves are located close to the thyroid cartilage, and they can be easily damaged during surgery if the surgeon is not careful. The surgeon must have a thorough understanding of the anatomy of the neck and be able to identify and protect these vital structures during the procedure.

Non-Surgical Management Options

Conservative management

For asymptomatic patients or those who decline surgery, conservative management may be an option [3]. Some patients with STCS may have only mild symptoms that do not significantly impact their quality of life. Other patients may be unwilling or unable to undergo surgery due to other medical conditions or personal preferences. In these cases, conservative management may be the best option. This includes observation and management of symptoms with medication [1]. Conservative management typically involves monitoring the patient’s symptoms and providing medications to relieve pain and inflammation. The patient may also be advised to avoid activities that exacerbate their symptoms, such as straining their voice or swallowing large pieces of food. However, conservative management does not address the underlying structural abnormality. While conservative management can provide symptomatic relief, it does not correct the underlying anatomical abnormality that is causing the symptoms. In some cases, the symptoms may worsen over time, requiring more aggressive treatment. Patients who choose conservative management should be closely monitored for any changes in their symptoms.

Medical management

Medications, such as pain relievers and anti-inflammatory drugs, can help manage throat pain and discomfort [1]. Over-thecounter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen, can help to relieve mild to moderate throat pain. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and naproxen, can help to reduce inflammation and pain. In some cases, stronger pain medications, such as opioids, may be necessary to manage severe throat pain. In cases where reflux is suspected, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be prescribed [7]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are medications that reduce the production of stomach acid. They are commonly used to treat acid reflux, which can cause throat pain and irritation. If the clinician suspects that acid reflux is contributing to the patient’s symptoms, a PPI may be prescribed. These treatments provide symptomatic relief but do not correct the anatomical issue. Medical management can help to relieve the symptoms of STCS, but it does not correct the underlying anatomical abnormality. In some cases, the symptoms may worsen over time, requiring more aggressive treatment. Patients who choose medical management should be closely monitored for any changes in their symptoms.

Potential Surgical Complications and Mitigation Strategies

Nerve injury

Injury to the superior laryngeal nerve or recurrent laryngeal nerve is a potential risk during surgery [4]. The superior laryngeal nerve and recurrent laryngeal nerve are important nerves that control the muscles of the larynx, which are responsible for voice production and swallowing. Damage to these nerves can result in hoarseness, voice changes, difficulty swallowing, and aspiration. The risk of nerve injury is higher during surgery to remove the superior cornu because these nerves are located in close proximity to the surgical site. Careful dissection and identification of these nerves are crucial to avoid damage. Surgeons must have a thorough understanding of the anatomy of the neck and be able to identify and protect these nerves during the procedure. Careful dissection techniques, such as using blunt dissection and avoiding excessive traction, can help to minimize the risk of nerve injury.

Vascular injury

The superior thyroid artery and carotid artery are in close proximity to the surgical field. Meticulous surgical technique and thorough knowledge of the regional anatomy are essential to prevent vascular injuries . Surgeons must have a thorough understanding of the anatomy of the neck and be able to identify and protect these vessels during the procedure. Meticulous surgical techniques, such as using gentle dissection and avoiding excessive traction, can help to minimize the risk of vascular injury.

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications may include infection, hematoma, and difficulty swallowing .Infection can occur if bacteria enter the surgical site. Hematoma is a collection of blood that can form under the skin. Difficulty swallowing can occur due to swelling or nerve injury. These complications can prolong the recovery period and may require additional treatment. Close monitoring and appropriate management are necessary to address these issues. Patients should be closely monitored for signs of infection, such as fever, redness, and swelling. Hematomas may require drainage. Contrast swallow studies can help detect any postoperative leaks or swallowing dysfunction [1]. A contrast swallow study is an imaging test that uses a special liquid to visualize the esophagus and stomach. This test can help to identify any leaks or strictures in the esophagus, as well as any problems with swallowing function. Contrast swallow studies are typically performed after surgery to remove the superior cornu to ensure that the patient is able to swallow safely.

Long-Term Outcomes and Prognosis

Resolution of symptoms

Surgical excision of the superior thyroid cornu typically leads to complete resolution of symptoms [1,3]. In most cases, patients experience significant improvement in their symptoms after surgery. The removal of the abnormal cartilage eliminates the source of irritation and compression, allowing the tissues to heal and function normally. Patients often experience significant improvement in dysphagia, throat pain, and globus sensation [3]. Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, typically improves as the pharyngeal space is no longer narrowed by the displaced cornu. Throat pain and globus sensation also tend to resolve as the irritation and inflammation of the pharyngeal mucosa and laryngeal nerves subside. Long-term follow-up is essential to monitor for any recurrence or complications [1]. Although surgical excision of the superior thyroid cornu is typically effective, there is a small risk of recurrence or complications. Patients should be followed up with regularly to monitor their symptoms and ensure that they are recovering properly. Follow-up may involve physical examinations, endoscopy, and imaging studies.

Functional outcomes/

Most patients regain normal swallowing function and experience improved quality of life [1]. After surgery and speech therapy, most patients are able to swallow normally and eat a regular diet. They also experience a significant improvement in their quality of life, as they are no longer burdened by the symptoms of STCS. However, some patients may require ongoing management for persistent symptoms [8]. In rare cases, some patients may continue to experience mild symptoms even after surgery and speech therapy. These patients may require ongoing management with medication, lifestyle modifications, or other therapies.

Recurrence rates

Recurrence of STCS is rare after successful surgical excision [1]. Once the abnormal cartilage has been completely removed, it is unlikely to grow back or cause further problems. However, there are some factors that may increase the risk of recurrence. However, long-term monitoring is important to detect any potential recurrence or new-onset symptoms [1]. Patients should be followed up with regularly to monitor their symptoms and ensure that they are recovering properly. Any new or worsening symptoms should be reported to the physician immediately. Further research is needed to identify factors that may contribute to recurrence. More research is needed to understand the longterm outcomes of surgical excision of the superior thyroid cornu and to identify any factors that may contribute to recurrence. This research can help to improve the treatment of STCS and ensure that patients receive the best possible care.

Conclusion

Superior Thyroid Cornu Syndrome is a rare but important differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic dysphagia, odynophagia, or throat discomfort. Recognition of this anatomical abnormality through endoscopy and imaging enables timely diagnosis and avoids unnecessary interventions. Surgical excision is effective and safe in symptomatic patients, while conservative management remains a viable option for those with milder symptoms.

References

- Akhtarzai A, Mohamad S (2025) Successful surgical management of superior thyroid cornu syndrome: a rare cause of cervical dysphagia. Saudi J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 27(1): 58-60.

- Wojtowicz P, Szafarowski T, Kukwa W, Migacz E, Krzeski A (2015) Extended superior cornu of thyroid cartilage causing dysphagia and throat pain. J Med Cases 6(3): 134-136.

- Abdul Razak SF, Azman M, Ping LS (2024) A laryngopharyngeal mass: pressure effect of the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage induced by a thyroid mass. Oman Med J 39(4): e656.

- Lechien JR, Buchet A, Doyen J, Saussez S, Legrand A (2024) Chronic cough related to thyroid cartilage superior cornu abnormality. Ear Nose Throat J.

- Nadig SK, Uppal S, Back GW, Coatesworth AP, Grace AR (2006) Foreign body sensation in the throat due to displacement of the superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage: two cases and a literature review. J Laryngol Otol 120(7): 608-609.

- Han CY, Long SM, Parikh NS, Phillips CD, Obayemi A, et al. (2022) Impingement of the thyroid cartilage on the carotid causing clicking larynx syndrome and stroke. Laryngoscope 132(7):1410-1413.

- Karaman E, Saritzali G, Albayram S, Kara B (2011) An unusual cause of foreign-body sensation in the throat: a displaced superior cornu of the thyroid cartilage. Ear Nose Throat J 90(6): E22-E24.

- Li CX, Hu L, Gong ZC (2023) Reconsideration of hyoid bone syndrome a case series with a review of the literature. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 124(1): 101263.