Abstract

Objective: This scoping review aimed to address the question: “What are the scientific evidences regarding the diagnosis, management, and prognosis of oral lesions in patients with Long COVID?” Materials and Methods: This investigation followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines as proposed in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual. The research protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) to facilitate open collaboration in scientific research. Results: The review highlighted a variety of oral lesions in Long COVID patients, including ulcers, leukoplakia, and fungal infections. Patients with Long COVID experience a diverse range of symptoms persisting weeks or months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, and neurocognitive dysfunctions. Oral symptoms include ulcers, throat inflammation, fungal infections, dry mouth, and loss of taste. Conclusions: These findings underscore the importance of an integrated approach in diagnosing and treating oral manifestations in Long COVID patients, contributing to the development of more effective clinical practices and guiding future research in this emerging field.

Keywords:Evidence-based health; Oral manifestations; Post-Covid Syndrome; Covid 19; Symptoms; Dentistry

Abbreviations:JBI: Joanna Briggs Institute; OSF: Open Science Framework; PHEIC: Public Health Emergency of International Concern; WHO: World Health Organization; LILACS: Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature; MeSH: Medical Subject Headings; ARB: Angiotensin Receptor Blockers; ACE: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic posed a significant challenge to public health worldwide. On May 5, 2023, during an Emergency Committee meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) related to Covid-19. The Committee highlighted that the decline in hospitalizations and intensive care unit admissions related to the disease, as well as the population's immunization through vaccines, marked the end of the pandemic status [1]. With the emergence of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, there was a substantial increase in primary and secondary publications due to researchers' efforts to address the lack of information about the new disease affecting the world. Although the scientific community has been successful in controlling the spread of this pathogen, there are still patients experiencing its sequelae [2]. Cases of Covid-19 with more prolonged symptoms have been increasingly reported in the literature [3,4]. Long Covid Syndrome, also known as Post-Covid Syndrome, is a set of symptoms that persist for more than three months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, even in patients who had mild or asymptomatic cases.

There is still no clear and consensual definition for the syndrome, but recent studies suggest it can affect up to 50% of patients infected with the virus [5]. Various studies have reported the presence of oral lesions in Covid-19 patients, including ulcerations, oropharyngeal inflammations, retromandibular edemas, fungal infections, xerostomia, anosmia, and ageusia [6,7]. Although these manifestations have been described in the literature, there is a lack of clinical guidelines addressing the specific oral conditions of patients with Long Covid, including appropriate treatment information, the healthcare professionals involved, and situations, if applicable, that require referral to specialists [8]. There are also studies in the literature describing multisystemic symptoms in Long Covid, involving various organ systems such as cardiovascular, respiratory, and digestive (including the mouth) [9,10]. Thus, secondary studies like scoping reviews can track articles with various methodological designs that have described oral lesions associated with Long Covid. Additionally, scoping reviews are essential for identifying gaps in the existing literature and understanding research trends in a specific field of knowledge [11]. Therefore, the objective was to survey the main oral lesions in patients affected by Long Covid based on scientific publications and identify the main clinical approaches and gaps observed in published studies on oral manifestations in Long Covid patients.

Material & Methods

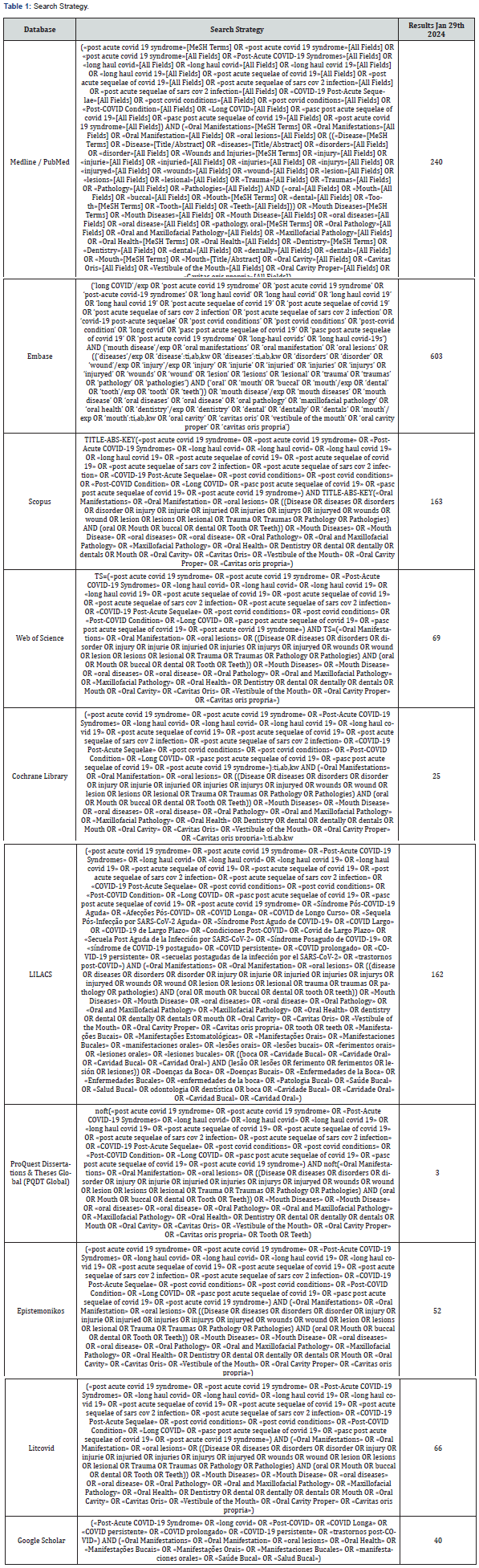

This work was registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) and used the PCC strategy, Population, Concept, and Context, to construct the research question. In this case, P = Patients with Long Covid; C = Oral lesions; C = Diagnosis, management, and prognosis. Based on these definitions, the guiding question was established: “What are the scientific evidence regarding the diagnosis, management, and prognosis of oral lesions in patients with Long Covid?” A survey of works published between 2020 and 2023 was conducted in the following databases: MEDLINE/Pubmed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), Cochrane Library, Epistemonikos, and Litcovid. The search equation was constructed with keywords and DECs (Health Sciences Descriptors) and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) descriptors adapted for each database, using Boolean operators AND and OR (Table 1) Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Primary and secondary studies without date restrictions were included to cover a broader range of studies on the main topic. Narrative or integrative reviews, letters to the editor, and articles in press were excluded. The reference list was managed using the Rayyan software. After eliminating duplicates, a preliminary selection was made by reading titles and abstracts. Both in the first and second phases, discrepancies in eligibility criteria were resolved among the reviewers during both processes. To improve the methodological rigor of the research, data extraction was performed by two blinded and independent reviewers, using the blinding option of the Rayyan tool [12]. The findings were presented according to the 'Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: extension for scoping reviews' checklist.

Search strategies were performed for each database by using specifics words combinations and truncations with the support of a librarian.

Results

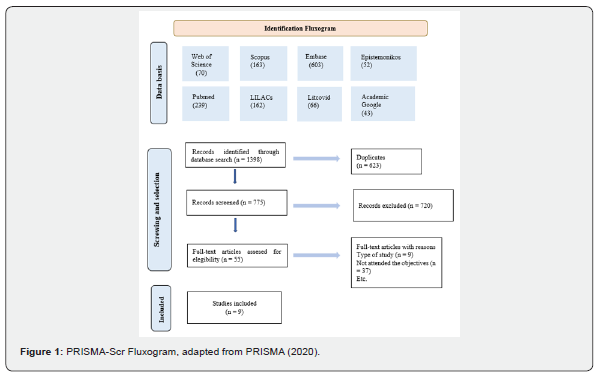

A total of 1,398 records were obtained, and 623 duplicate studies were then removed. One article was included after a manual search, resulting in 776 articles to be evaluated. Most of the excluded articles dealt with the global understanding of long COVID, such as cognitive dysfunctions, "brain fog," olfactory dysfunction, and facial paralysis. Additionally, these studies also addressed the impacts on quality of life and the difficulties patients face in seeking adequate care within their countries' healthcare systems, often due to the lack of physicians capable of recognizing and understanding this new condition. After this screening, 56 articles remained for full-text evaluation. The second phase began with a complete reading of the selected articles. In this stage, nine publications consisting of narrative reviews or letters to the editor, which did not meet the established inclusion criteria, were excluded. Additionally, 37 other articles were excluded for not aligning with the research objectives. Among these, two articles addressed long COVID in a population of dental professionals, while the remaining 35 dealt with other long COVID-related manifestations such as dysgeusia, xerostomia, osteonecrosis, and periodontal disease.

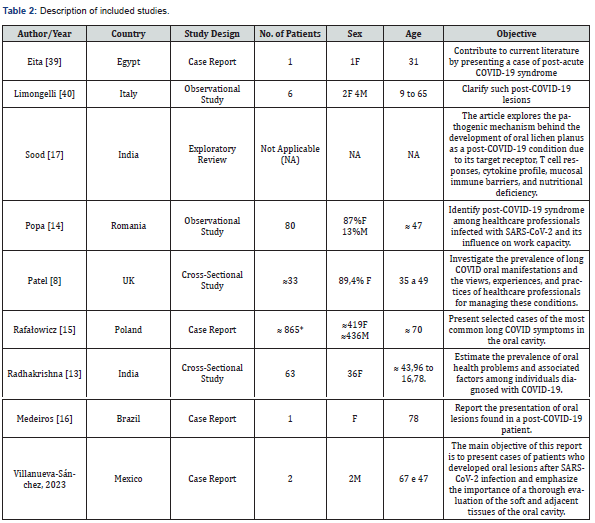

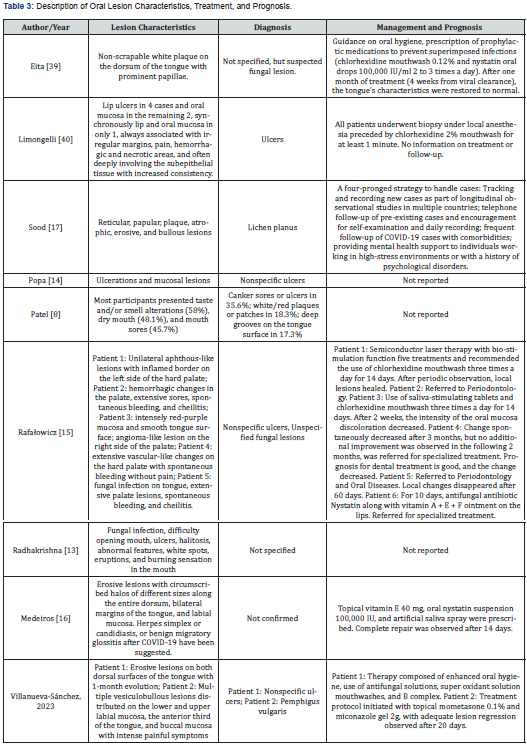

Although these studies were not included in the review, they will be considered for later discussion. At the end of this stage, nine articles remained, which will be the subject of this review. The process is summarized in the Prisma Flowchart (Figure 1). This study, composed of nine publications, investigated a total of approximately 1,051 patients addressed in the studies, with the exception of an exploratory study that did not report the number of patients involved. The findings described in the methodological design and results of the included studies are detailed in Table 2 & 3. Regarding the publication year, it was observed that the publications span from 2020 to 2024, highlighting the emerging nature of this topic. As for the study locations, there was a wide heterogeneity, including countries such as Brazil, India, Italy, Egypt, Romania, the United Kingdom, Mexico, and Poland. In terms of study design, Case Reports, Observational Studies, Cross-Sectional Studies, and an Exploratory Review were found, which also signals that this is a recent topic still lacking systematic reviews. The analysis of data on the management and prognosis of the lesions revealed a variety of therapeutic approaches and clinical outcomes. Guidance on oral hygiene and the prescription of prophylactic medications were common, including chlorhexidine mouthwash and medications to prevent superimposed infections, such as Nystatin. Some patients received specific treatments, such as laser therapy and the use of saliva-stimulating medications.

In some cases, the oral lesions disappeared spontaneously after a few weeks, while others required specialized treatment due to the persistence or severity of the manifestations. Both Cross-Sectional Studies by Patel et al. [8] and Radhakrishnan et al. [13] were conducted in the form of online questionnaires and did not report on the management and prognosis of the patients' lesions. Additionally, Popa's et al. [14] Observational Study was limited to analyzing the occurrence and impact of the lesions and also did not report these data. Some studies, such as Patel et al. [8] and Radhakrishnan et al. [13], included patients at different stages, both in the acute and prolonged phases of COVID-19, in their sample. However, they did not provide a clear differentiation in their percentage data regarding the types of lesions per patient concerning which corresponded to long COVID. Moreover, a lack of standardization was observed in the classification or diagnosis of the lesions, which were often generically described as ulcers, plaques, or fungal lesions without specifying the precise diagnosis (e.g., herpes, erythema multiforme, etc.). These limitations hindered the approach and comparison concerning the number of lesions per patient. Therefore, to express in quantitative data the type of oral lesion reported in the patients from the nine studies included in this review, the number of times the lesions were cited was counted. Nonspecific ulcers were the most common, representing 40% of the citations, followed by leukoplakia (20%), fungal lesions (13.3%), among others (Graph 1). These findings suggest a variety of oral manifestations associated with long COVID.

According to the article, among 1,256 patients, oral symptoms appeared in 68% of them.

Although opportunistic lesions such as herpes simplex and candidiasis were identified in some studies [8,15,13], it is important to note that due to the study designs, patients were not assessed in person. As a result, diagnostic specificity was compromised, and the lesions were described generically without precise distinction between different conditions. For example, in Medeiros et al. [16] study, although a possible secondary infection was suggested, the diagnosis was not clinically confirmed. Among the selected articles, the observational study conducted by the "Stomatologia Rafałowicz" clinic, published by Rafałowicz et al. [15], stands out, with a significant incidence of oral symptoms in patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Of the 1,256 patients studied, 68% had oral cavity symptoms, indicating the presence of post-acute oral sequelae of COVID-19. These symptoms included discoloration, ulceration, and hemorrhagic changes in the oral mucosa (32%), tongue mycosis (29.69%), unilateral aphthous-like lesions on the hard palate (25.79%), and atrophic cheilitis (12.5%). The authors of the study also observed that approximately 36% of patients chose not to follow the proposed treatment, opting only for oral hygiene recommendations and regular check-ups, and it was noted that most pathological changes spontaneously disappeared in this group after 3 weeks. Regarding the location of the lesions, it was possible to ascertain that oral lesions associated with long COVID have a pattern similar to the acute form. The most frequently cited locations were the buccal mucosa, lips, and tongue. Three studies did not identify the location of the lesions [13,8,17].

Discussion

A significant portion of individuals who survived COVID-19 are at risk of developing long-term nonspecific sequelae, a condition known as Long COVID [18]. Long COVID symptoms vary widely, including fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, joint pain, brain fog, and other neurological and psychological manifestations. Identifying factors associated with Long COVID is an emerging public health priority due to its lasting and debilitating potential [19]. Moreover, many older adults receive angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors to manage chronic illnesses. However, these medications upregulate ACE2 receptors-the same receptors used by SARS-CoV-2 to enter host cells. Consequently, patients on these medications face an elevated risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Additionally, older patients who survived COVID-19 may experience organ damage, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, and cardiac issues [20]. The relationship between Long COVID and the emergence of persistent oral lesions is under investigation. Studies have shown that pathological changes in the oral cavity can persist long after acute infection. According to Melo Neto et al. [21], these changes can appear between 10 to 42 days after the onset of systemic COVID-19 symptoms and persist for 2 to 6 months, manifesting as ulcers, plaques, fungal lesions, and other mucosal changes.

Data from this study indicate a predominance of cases in men in some samples, while others show a predominance in women, suggesting that Long COVID may affect sexes differently. A study by Davis et al. [22] revealed a 4:1 disease burden for women in 56 countries, indicating that although men more frequently test positive and suffer more severe illness, females are more likely to develop post-acute syndrome. Regarding age, Long COVID affects a wide range, from young adults to the elderly, but most studies focus on middle-aged and older adults, with an average age of around 47 years. Approximately 30% of reported patients are over 70, suggesting that the elderly may be at higher risk of developing Long COVID. Nalbandian et al. [23] identified older age, higher BMI, and five or more acute COVID-19 symptoms as risk factors for developing persistent symptoms. A retrospective cohort study of 2,433 patients followed for a year indicated that advanced age, female sex, and severe COVID-19 predispose individuals to long-term sequelae [24]. Recent evidence by Banks et al. [25] shows SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to oral manifestations like xerostomia, dysgeusia, periodontal disease, mucositis, and opportunistic infections, aligning with past findings of viruses like HIV, CMV, and herpesvirus persisting in the oral cavity [26-29].

Amorim dos Santos et al. [30] noted that stress, inflammation, and corticosteroid use could trigger HHV reactivation, explaining herpes simplex in some patients. Brandini et al. [31] suggested treatments for viral infections like COVID-19 might cause adverse reactions leading to oral lesions such as candidiasis and gingivitis. Zubchenko et al. [32] observed Long COVID triggering herpes reactivation, reinforcing the link between SARS-CoV-2 and oral lesions. Huang et al. [33] found the virus detectable in saliva for over 2 months in some symptomatic individuals and up to 3.5 weeks in asymptomatic cases. Therapeutic strategies for Long COVID oral lesions lack standardization. However, treatments for acute COVID-19 oral manifestations may guide these cases, including 2% chlorhexidine for lacerations, hyaluronic acid, and tranexamic acid for bleeding control, and miconazole for diagnosed candidiasis [34,35]. Many COVID-19 treatments, such as analgesics, antivirals, antibiotics, and immunomodulators, also treat oral conditions but may have long-term adverse effects impacting dental management of Long COVID lesions [36,37].

This study's findings align with literature citing these lesions as frequently associated with COVID-19 and similarly with Long COVID, highlighting the importance of tracking and documenting these occurrences in primary studies to support consistent epidemiological research. As Binmadi et al. [38] discussed, it's crucial to clarify which oral manifestations persist in Long COVID to establish it as a clinical diagnosis after excluding other common causes, allowing for effective management of these conditions and early identification of patients needing specific interventions. This scoping review mapped the landscape of Long COVID-associated oral lesions, highlighting lesion types and patient characteristics. However, limitations include not searching thesis and dissertation databases and not assessing methodological quality or bias risk of included studies, which may affect data reliability. Nonetheless, the study's strength lies in mapping oral lesion occurrences in Long COVID patients and identifying knowledge gaps, particularly in management and prognosis. This contributes to understanding associated symptoms and benefits health services by identifying these conditions that compromise quality of life [39,40].

Conclusion

In summary, this scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of the current evidence on oral manifestations in Long Covid patients. The findings underscore the importance of continued research and the development of clinical guidelines to address this emerging aspect of post-acute sequelae of Covid-19. By advancing our understanding of these oral manifestations and their management, we can improve the care and outcomes for Long Covid patients, ultimately contributing to the broader efforts to address the ongoing challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

References

- OPAS (2023) OMS declares an end to the public health emergency of international concern regarding the COVID-19.

- Chen Q (2023) Lit Covid in 2022: an information resource for the COVID-19 literature. Nucleic Acids Research 51(1): D1512-D1518.

- Stavem K (2021) Prevalence and determinants of fatigue after COVID-19 in non-hospitalized subjects: a population-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4): 2030.

- Sigfrid L (2021) Long Covid in adults discharged from UK hospitals after Covid-19: A prospective, multi center cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterization Protocol. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe 8.

- (2022) Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. Fiocruz research evaluates long Covid syndrome.

- Sapkota D (2022) Expression profile of SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular entry proteins in normal oral mucosa and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical and Experimental Dental Research 8(1): 117-122.

- Xu R (2020) Saliva: potential diagnostic value and transmission of 2019-nCoV. Int j Oral Sci 12(1): 11.

- Patel D, Louca C, Vargas CM (2023) Oral manifestations of long COVID and the views of healthcare professionals.

- Afrisham R (2023) Long-term gastrointestinal, hepatic, pancreatic, oral, and psychological symptoms of COVID-19 after recovery: a review. Mini Rev Med Chem 23(7): 852-868.

- Mohiuddin C, Abu Taiub M (2021) Clinical characteristics and the long-term post-recovery manifestations of the COVID-19 patients-A prospective multicenter cross-sectional study. Front Med 8: 663670.

- Cordeiro L, Soares CB (2019) Scoping review: potentialities for the synthesis of methodologies used in qualitative primary research. BIS. Health Institute Bulletin 20(2): 37-43.

- Johnson N, Margaret P (2018) Rayyan for systematic reviews. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship 30(1): 46-48.

- Athira R, Avani D, Aswathy S, Minu MM (2023) Prevalence of Oral Health Issues and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Post-COVID Patients in Kannur, Kerala: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clinical Medicine 1(1): 70-74.

- Popa MV (2023) Observational study of post-covid-19 syndrome in health care workers infected with sars-cov-2 virus: general and oral cavity complications. Romanian Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 15(3).

- Rafałowicz B, Wagner L, Rafałowicz J (2021) Long COVID oral cavity symptoms based on selected clinical cases. Eur J Dent 16(2): 458-463.

- Medeiros YL, Guimarães LDA (2021) Oral Lesions Associated with Post-COVID-19: Disease Sequels or Secondary Infection?. Int J Odontostomat 15(4): 812-816.

- Sood A (2021) Rise and exacerbation of oral lichen planus in the background of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Medical Hypotheses 156: 110681.

- Lai CC (2023) Long COVID: An inevitable sequela of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infec 56(1): 1-9.

- Feter N (2023) Prevalence and factors associated with long COVID in adults from Southern Brazil: findings from the PAMPA cohort. Cad Saude Publica 39: e00098023.

- Marchini L, Ronald L (2020) COVID-19 and Geriatric Dentistry: What will be the new-normal?. Brazilian Dental Science 23(2): 7.

- Melo N, Clóvis LM (2020) SARS-CoV-2 and dentistry–review. European Journal of Dentistry 14: S130-S139.

- Davis Hannah E (2021) Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine.

- Nalbandian A (2021) Syndrome Pós-Aguda COVID-19. Nat Med 27(4): 601-615.

- Zhang X (2021) Symptoms and health outcomes among survivors of COVID-19 infection 1 year after discharge from hospitals in Wuhan, China. JAMA Network open 4(9): e2127403-e2127403.

- Banks JM (2024) Herpesviruses and SARS-CoV-2: Viral Association with oral inflammatory diseases. Pathogens 13(1): 58.

- Pallos D (2020) Periodontal disease and detection of human herpesviruses in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid of chronic kidney disease patients. Journal of Periodontology 91(9): 1139-1147.

- Contreras A, Nowzari H, Slots J (2000) Herpesviruses in periodontal pocket and gingival tissue specimens. Oral Microbiol Immunol 15(1): 15-18.

- Matičić M (2000) Proviral HIV-1 DNA in gingival crevicular fluid of HIV-1-infected patients in various stages of HIV disease. J Dent Res 79(7): 1496-1501.

- Parra B, Slots J (1996) Detection of human viruses in periodontal pockets using polymerase chain reaction. Oral Microbiol Immunol 11(5): 289-293.

- Amorim DS (2021) Oral manifestations in patients with COVID-19: a 6-month update. Journal of Dental Research 100(12): 1321-1329.

- Brandini DA (2021) Covid‐19 and oral diseases: Crosstalk, synergy or association? Rev Med Virol 31(6): e2226.

- Zubchenko S (2022) Herpesvirus infections and post-COVID-19 manifestations: a pilot observational study. Rheumatol Int 42(9): 1523-1530.

- Huang Ni (2021) SARS-CoV-2 infection of the oral cavity and saliva. Nature Medicine 27(5): 892-903.

- Favia G (2021) COVID-19 symptomatic patients with oral lesions: clinical and histopathological study on 123 cases of the University Hospital Policlinic of Bari with a purpose of a new classification. Journal of Clinical Medicine 10(4): 757.

- Gutierrez C, Jose R (2022) Oral lesions associated with COVID-19 and the participation of the buccal cavity as a key player for establishment of immunity against SARS-CoV-2. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(18): 11383.

- Dar Odeh (2021) What the dental practitioner needs to know about pharmaco-therapeutic modalities of COVID-19 treatment: A review. Journal of Dental Sciences 16(3): 806-816.

- Ohashi N (2021) Oral candidiasis caused by ciclesonide in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia: A case report and literature review. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports 9: 2050313X211048279.

- Binmadi N (2022) Oral manifestations of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study of their prevalence and association with disease severity. Journal of Clinical Medicine 11(15): 4461.

- Eita A (2021) Abdelmoniem Bedeir. Parosmia, Dysgeusia, and Tongue Features Changes in a Patient with Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Case Reports in Dentistry.

- Limongelli L (2023) Oral lesions with immunohistochemical evidence of Sars‐CoV‐2 in swab‐negative post‐COVID syndrome. Oral Diseases.