Abstract

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPDD) rarely involves the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). In the absence of characteristic clinical or radiological clues, it can mimic both benign and malignant neoplasms. We present a challenging case of CPPD manifesting as a pre-auricular mass that clinically and radiologically resembled a parotid neoplasm. Initial standard histological evaluation was non-diagnostic. The correct diagnosis relied on identifying rhomboid, birefringent crystals retrospectively on frozen section slides and fine needle aspiration (FNA) smears. This manuscript explores the diagnostic complexities associated with atypical CPPD presentations and emphasizes essential diagnostic roles of frozen section tissue and FNA using Diff-Quik staining in diagnosing CPPD when clinical and radiological features are inconclusive.

Keywords:CPPD; temporomandibular joint (TMJ); parotid; frozen section; FNA

Introduction

CPPD, also known as pseudogout, is a crystal arthropathy characterized by the deposition of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals in cartilage and synovium, typically involving larger joints. It is associated with metabolic disorders including hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, and hemochromatosis but may also occur idiopathically [1]. Although commonly presenting with joint inflammation, swelling, and pain, CPPD can also manifest atypically as peri-auricular masses that mimic parotid gland tumors or other TMJ disorders, leading to diagnostic challenges including delayed or missed diagnosis as well as potentially inappropriate interventions [2-5].

Case Presentation : An 88-year-old woman presented with a firm, fixed and non-tender pre-auricular mass that progressively enlarged over several months. Patients’ medical history was significant for chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 2.1 cm cystic lesion with peripheral enhancement within the right parotid gland adjacent to the degenerative TMJ, with focal bone destruction. Due to its proximity to TMJ and associated bony erosion, malignancy was suspected, necessitating further investigation. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology yielded acellular viscous fluid with extracellular chondromyxoid matrix, inconclusive for malignancy. The patient underwent surgery where intraoperatively an enlarged, degenerative TMJ capsule was found to be intimately adherent to the mass. Intraoperative frozen consultation showed fibrotic lesion with calcification.

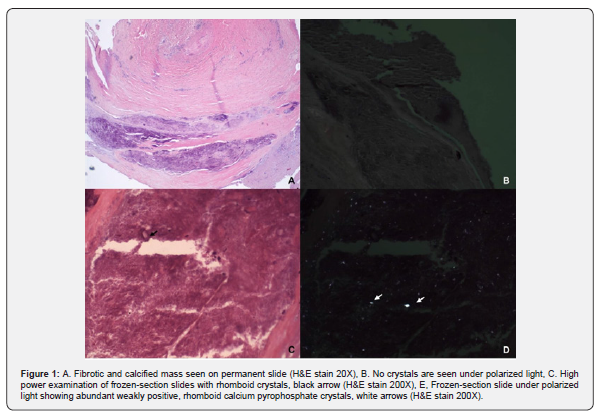

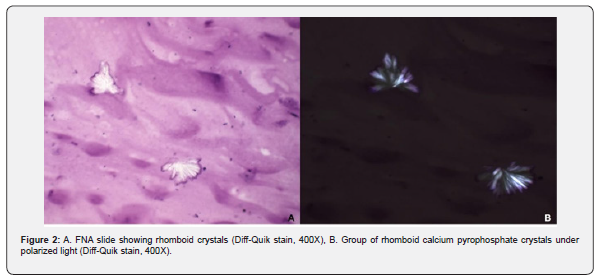

Initial examination of the permanent H&E sections revealed a fibrotic mass with calcifications and chondro- osseous changes, prompting consideration of a synovial-type neoplasm. Detailed review of frozen-section slides under polarized light revealed abundant, rhomboid, birefringent crystals, far more numerous than permanent H&E slides (Figure 1). Retrospective review of the FNA samples using Diff-Quik staining identified identical rhomboid crystals as seen in frozen-section slides. (Figure 2). Radiological and clinical correlation was performed. Subsequently, definitive CPPD diagnosis was established through analysis of frozen section slides, highlighting abundant birefringent rhomboid crystals not visible or substantially diminished in routine histological preparations.

Discussion

CPPD is a crystal-induced arthropathy commonly affecting large joints such as the knees and wrists. Atypical presentations involving the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and rarely parotid, have been documented. In such cases the calcified crystal mass occupies the TMJ space, inducing pre-auricular swelling, pain, tenderness, and even impaired joint movement. [3-6]. A recentreview emphasized the variability in CPPD manifestations and diagnostic pitfalls, calling for heightened clinical awareness and more standardized diagnostic approaches [7]. These unusual manifestations can mimic neoplastic processes, particularly in the parotid region, posing significant diagnostic challenges [4,8,9].

Histopathological evaluation of CPPD typically reveals basophilic, granular deposits of calcium pyrophosphate crystals within fibrous or cartilaginous tissues, often surrounded by a chronic inflammatory response, though these features may be subtle or absent in routine sections [10]. In the presented case, initial evaluation of the pre-auricular mass in conjunction with bony destruction of degenerated TMJ raised concerns for malignancy. FNA findings in the absence of clinical clues were non-specific. Microscopic examination of the excised mass demonstrated a fibrotic mass with calcifications, chondroid differentiation, and bony erosion. These features, in the absence of definitive crystal identification might be suggestive of a neoplastic process and could be misinterpreted. Routine hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining failed to conclusively identify CPPD crystals like FNA slides. The utilization of frozen section analysis in this case was pivotal. By relying on unfixed and unprocessed tissue, the integrity of calcium pyrophosphate crystals was preserved, allowing for their visualization under polarized light microscopy. Identifying characteristic rhomboid-shaped, weakly positively birefringent crystals confirmed the diagnosis of CPPD.

Retrospective analysis of the FNA specimen, employing Diff- Quik staining, also revealed similar crystals, underscoring the utility of this rapid staining technique in cytological preparations [11-13]. Routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining often fails to reveal CPPD crystals due to their solubility in alcohol-based fixatives and decalcifying agents used during tissue processing [14,15]. In their study, Shidham and Shidham highlighted the limitations of routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in detecting urate crystals within formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. They introduced a nonaqueous alcoholic eosin staining (NAES) method, which avoids aqueous reagents and better preserves the birefringent properties of urate crystals. The NAES technique demonstrated superior visualization of these crystals under polarized light microscopy compared to traditional H&E staining, which often fails to reveal them due to their solubility in alcohol-based fixatives and decalcifying agents. Our findings are in agreement with previous findings in that the slide prepared during intraoperative consultation without formalin fixation or decalcification clearly demonstrated abundant rhomboid crystals.

This case also highlights the importance of considering CPPD in the differential diagnosis of peri-auricular masses, especially in elderly patients with metabolic risk factors. Misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary surgical interventions and patient morbidity. Clinicians and pathologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for CPPD in atypical presentations and employ appropriate diagnostic modalities, including frozen section analysis and specialized staining. Early and accurate diagnosis is essential for appropriate management which may include anti-inflammatory medications and avoidance of unnecessary surgical management [16-19]. This case emphasizaes the need for awareness of the limitations of routine histological processing in detecting crystal induced arthropathies.

Conclusion

CPPD should be considered in differential diagnoses of peri-auricular masses resembling parotid neoplasms. Given the solubility of CPPD crystals in routine histological preparations, frozen section tissue analysis and FNA using Diff-Quik staining significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy, guidi ng appropriate management and preventing unnecessary interventions.

References

- Rosenthal AK, Ryan LM (2016) Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease. N Engl J Med 374(26): 2575-2584.

- Ishida T, Dorfman HD, Bullough PG (1995) Tophaceous pseudogout (tumoral calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease). Hum Pathol 26(6): 587-593.

- Naqvi AH, Abraham JL, Kellman RM, Khurana KK (2008) Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD)/Pseudogout of the temporomandibular joint - FNA findings and microanalysis. Cytojournal 5:8.

- Kwon KJ, Seok H, Lee JH, Kim MK, Kim SG, et al. (2018) Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease in the temporomandibular joint: diagnosis and treatment. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 40(1): 19.

- Ayub B, Frare D, Romagnolli L (2003) Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease (tophaceous pseudogout) of the temporomandibular joint: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol 35(3): 219-223.

- Tang T, Han FG (2021) Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease of the temporomandibular joint invading the middle cranial fossa: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 9(11): 2662- 2670.

- Voulgari PV, Venetsanopoulou AI, Drosos AA (2024) Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease: historical overview and potential gaps. Front Med (Lausanne) 11: 1380135.

- Bschorer F, Höller S, Baumhoer D, Bschorer R (2024) Pseudogout growing from the temporomandibular joint into the middle cranial fossa. Oral Maxillofac Surg 28(1): 441–445.

- Marsot Dupuch K, Smoker WR, Gentry LR, Cooper KA (2004) Massive calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease: a cause of pain of the temporomandibular joint. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 25(5): 876–879.

- McCarty DJ, Carrera GF, Ryan LM (2001) Pathology and pathogenesis of calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res (391): 59-68.

- Subramanian H, Gochhait D, Ganesh RN, Govindarajalou R, Siddaraju N (2018) Diagnosis of pseudo- gout (calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease) clinched on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol 46(9): 748-751.

- Selvi E, Manganelli S, Catenaccio M, De Stefano R, et al. (2001) Diff Quik staining method for detection and identification of monosodium urate and calcium pyrophosphate crystals in synovial fluids. Ann Rheum Dis 60(3):194-198.

- Fan J, Heimann A, Wu M (2019) Temporal mandibular joint chondrocalcinosis (tophaceous pseudogout) diagnosed by ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol 47(8): 803- 807.

- Bély M, Apáthy Á (2018) Metabolic Diseases and Crystal Induced Arthropathies: Technic of Non- Staining Histologic Sections—A Comparative Study of Standard Stains and Histochemical Reactions. Clin Arch Bone Joint Dis 1(1): 007.

- Shidham V, Shidham G (2000) Staining method to demonstrate urate crystals in formalin-fixed, paraffin- embedded tissue sections. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124(5): 774-776.

- Val M, Ragazzo M, Colonna A, Ferrari M, Ferrari Cagidiaco E, et al. (2025) Pseudogout of the temporomandibular joint: a case report with systematic literature review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 39(1): 49-69.

- Kang X, Gao X, Chen G (2024) A rare case of atypical tumoral presentation of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease. Quant Imaging Med Surg 14(8): 1545-1549.

- Rana M S, Raza M, Arif M (2023) Confusion with Presentations of Calcium Pyrophosphate Dihydrate Disease: A Report of Two Cases Mistaken for Cellulitis. Cureus 15(2): e34789.

- Voulgari PV, Venetsanopoulou AI, Drosos AA (2024) Recent advances in the therapeutic management of calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. Front Med 11: 1327715.