Preventing Thyroid Diseases with a Plant-Based Diet, While Ensuring Adequate Iodine Status

Stewart Rose and Amanda Strombom*

Plant-Based Diets in Medicine, USA

Submission: January 23, 2020; Published: February 04, 2020

*Corresponding author: Amanda Strombom, Bellevue, Plant-Based Diets in Medicine, USA

How to cite this article: R Stewart, S Amanda. Preventing Thyroid Diseases with a Plant-Based Diet, While Ensuring Adequate Iodine Status. Glob J Oto, 2020; 21(4): 556069. DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2019.20.556069

Abstract

People with thyroid disorders in the US usually have an autoimmune disease, such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or Grave’s disease. Those following a plant-based diet are much less susceptible to auto-immune diseases in general. They also have a lower BMI on average. Since obesity is a significant risk factor for hypothyroidism, this contributes to the lower risk of hypothyroidism among vegans. However even after controlling for BMI and potential demographic confounders, vegans have been shown to experience a 22% lower risk of hypothyroidism, and a 51% risk of hyperthyroidism. Given that they are unlikely to be consuming any seafood or dairy, iodine deficiency is a greater possibility for those following a plant-based diet. Studies show that many vegans have very adequate iodine status, but some are deficient. The median is mildly deficient, but the range can vary greatly.

Very low iodine intake can reduce thyroid hormone production even in the presence of elevated TSH levels. However, high intakes of iodine can cause some of the same symptoms as iodine deficiency—including goiter, elevated TSH levels, and hypothyroidism—because excess iodine in susceptible individuals inhibits thyroid hormone synthesis and thereby increases TSH stimulation, which can produce goiter. Laboratory tests that detect abnormal thyroid function may be more useful for diagnosing chronic iodine deficiency or excessive iodine intake and for monitoring the effects of iodine supplementation.

Introduction

Hypothyroidism

While the lack of iodine in the diet is the biggest risk factor for hypothyroidism worldwide, in the United States, obesity is a significant risk factor for hypothyroidism [1]. The relation between obesity and hypothyroidism appears to have several explanations. Obesity may result in raised Thyroid Stimulating Hormone [TSH] levels, partly due to a proinflammatory milieu and other endocrine derangements [2]. Persons with obesity are prone to develop autoimmune hypothyroidism, and even mild thyroid failure contributes to the progressive increase in body weight, which ultimately results in overt obesity [3]. So elevated TSH levels may be both the consequence and the cause of obesity [2].

Vegans have a lower BMI on average [4] thus reducing their risk of hypothyroidism. However, the lower risk of hypothyroidism among vegans exists, even after controlling for BMI and potential demographic confounders [5]. One study showed that following a vegan diet tended to be associated with a 22% reduced risk of hypothyroidism, although statistical significance was not quite attained [5].

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is a prevalent condition with many causes, of which the most common is Graves’ disease [6]. Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder caused by antibodies directed against the thyrotropin receptor, resulting in excess synthesis and secretion of thyroid hormone [7]. The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES III] showed the prevalence of hyperthyroidism in the United States to be 1.3% [8].

While the specifics of hyperthyroidism and diet have not been extensively studied, observations by Trowel five decades ago indicated that for rural sub-Saharan Africans consuming a near-vegan diet, a number of autoimmune disorders were rare, or virtually unknown, including thyrotoxicosis and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [9]. Data from the Adventist Health Study showed that a vegan diet reduced the risk of hyperthyroidism by 51% while a vegetarian diet reduced the risk by 28% showing a dose response relationship [7].

This is to be expected since epidemiological studies have shown that vegetarians have lower risks of auto immune diseases in general. For instance, one study on Rheumatoid Arthritis [RA] showed that non-vegetarian women had a 57% increased risk of contracting RA, and semi-vegetarians an increased risk of 16%, when compared with vegetarian women. Non-vegetarian men showed an increased risk of 50% and semi-vegetarian men an increased risk of 14% [10]. An epidemiological study found that the risk of Crohn’s disease reduced by 70% in females and 80% in males following a vegetarian diet [11].

Iodine Insufficiency

The most common cause of thyroid disorders worldwide is iodine deficiency, leading to goiter formation and hypothyroidism. In iodine-replete areas, most persons with thyroid disorders have an autoimmune disease, primarily Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [12]. Iodine deficiency can lead to a variety of medical problems at all ages in the humans. This is a special concern for pregnant women. Children of mothers having an iodine deficiency during pregnancy may have mental retardation, deaf mutism, spasticity and short stature. Congenital hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency is the most common cause of preventable mental retardation in the world [13]. Despite ongoing public health efforts, iodine deficiency affects more than 2.2 billion individuals and remains the leading cause of preventable mental retardation worldwide [14].

The earth’s soils contain varying amounts of iodine, which in turn affects the iodine content of crops. In some regions of the world, iodine-deficient soils are common, increasing the risk of iodine deficiency among people who consume foods primarily from those areas. Worldwide, the soil in large geographic areas is deficient in iodine. 29% of the world’s population is estimated to live in areas of deficiency [15]. In the United States, before the 1920s and the introduction of iodized salt, iodine deficiency was common in the “goiter belt”—the Great Lakes, Appalachian, and the Pacific Northwest, and throughout most of Canada [16]. Programs to iodize salt have been implemented in many countries, significantly reducing the prevalence of iodine deficiency worldwide [14,17,18].

In the United States table salt is available as iodized with potassium iodide, which is used by about 50%–60% of the U.S. population. However, the U.S. population receives only a small percentage of its salt from table salt because 70% of dietary salt is derived from processed food, which uses mostly non iodized salt. [19] A reduction in iodine intake can also be related to reduced salt intake for the treatment and prevention of essential hypertension [13].

Iodine Status

Population iodine sufficiency is defined by median urinary iodine concentrations [14] (Table 1). Urinary iodine reflects dietary iodine intake directly because people excrete more than 90% of dietary iodine in the urine. [20] Iodine deficiency is diagnosed when the median iodine concentration is less than 50 μg/ml in a population [18]. Between 1971 and 2008, urinary iodine levels less than 50 μ g/liter among U.S. women of childbearing age rose from 4 to 15% [21].

Under normal conditions, the body tightly controls thyroid hormone concentrations via Thyroid Stimulating Hormone [TSH] which is produced by the pituitary gland. The thyroid gland secretes the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine [T3] and thyroxine [T4] in response to TSH [also known as thyrotropin]. The vast majority of T4 [99.97%] and T3 [99.70%] is tightly bound to thyroxine binding globulin [TBG] and other plasma proteins, and it is only the unbound or free thyroid hormones that are bioactive. Serum TSH is the most sensitive early indicator of thyroid dysfunction [22]. Typically, TSH secretion increases when iodine intake falls below about 100 mcg/day [18]. TSH increases thyroidal iodine uptake from the blood and the production of thyroid hormone.

TSH is regulated by circulating serum free thyroxine [FT4]. Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as elevated serum TSH in the setting of normal FT4. In overt hypothyroidism, serum TSH is elevated and serum FT4 is low. Serum free and total T3 concentrations usually do not decline until hypothyroidism is quite advanced, because elevated TSH stimulates the release of T3 from the thyroid [23].

However, very low iodine intakes can reduce thyroid hormone production even in the presence of elevated TSH levels. If a person’s iodine intake falls below approximately 10–20 mcg/ day, hypothyroidism occurs [24], a condition that is frequently accompanied by goiter. Moderate to severe iodine deficiency may produce lower serum FT4 and consequent elevation of serum TSH. If the iodine deficiency is prolonged, goiter may develop and there may be an increase in circulating concentrations of thyroglobulin [Tg] [25] This possibility should be considered when reviewing lab results.

High intakes of iodine can cause some of the same symptoms as iodine deficiency—including goiter, elevated TSH levels, and hypothyroidism—because excess iodine in susceptible individuals inhibits thyroid hormone synthesis and thereby increases TSH stimulation, which can produce goiter. [17,26] Excess iodine may induce hyperthyroidism in some patients, resulting in elevated FT4 and depressed TSH [27].

Risk of Fibrocystic Breast Disease

Fibrocystic breast disease is a benign condition characterized by lumpy, painful breasts and palpable fibrosis. It commonly affects women of reproductive age, but it can also occur during menopause, especially in women taking hormone replacement [28]. Breast tissue has a high concentration of iodine, especially during pregnancy and lactation] [20,29]. Some research suggests that iodine supplementation might be helpful for fibrocystic breast disease [30].

In a double-blind study, researchers randomly assigned women with fibrocystic breast disease to receive daily supplements of iodine or placebo for 6 months [28]. At treatment completion, 65% of the women receiving iodine reported decreased pain compared with 33% of women in the placebo group. A more recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial had similar findings [30]. Women receiving supplemental iodine had a significant decrease in breast pain, tenderness, and nodularity compared with those receiving placebo. The researchers also reported a dose-dependent reduction in self-assessed pain. None of the doses was associated with major adverse events or changes in thyroid function test results though large doses of iodine were used.

Iodine deficiency has been proposed to play a causative role in the development of breast cancer [31,32]. Dietary iodine has also been previously proposed to play a protective role in breast cancer [33]. The importance of iodine in breast cancer is further emphasized by the adjuvant effects of iodine [34] supplementation in combination with doxorubicin for breast cancer treatment [35]. In these studies, iodine treatment resulted in reduced tumor size and proliferating cell nuclear antigen [PCNA] expression.

Based on the importance of iodine in thyroid and breast health, fetal brain development, as well as deficits in nutritional trends among younger women, iodine testing and management may be considered as a potentially important aspect for clinical practice [36].

Risk for those Following a Plant-Based Diet

Primary sources of iodine for a non-vegan are seafood and dairy products. Milk contains iodine due to the teat cleansers typically used in dairies. Since a plant-based diet does not include seafood or dairy, concern has been expressed that vegans may be more prone to iodine deficiency.

Studies show that many vegans have very adequate iodine status, but some are deficient [37]. The median, however, is mildly deficient. In a study of vegans in the Boston area, median urinary iodine concentration of vegans was lower than for omnivores [78.5 μg/liter] but the range varied enormously [6.8 - 964.7 μg/ liter] [37]. However, it is reassuring that this was not associated with thyroid dysfunction. Other studies of thyroid function in vegetarians and vegans are limited. Although serum TSH was generally normal in 101 British vegans, the geometric mean was 47% higher than for omnivores [38]. No thyroid function abnormalities were found in studies Swedish and Finnish vegans [39,40]. Although thyroid function is usually good, patients on a plant-based diet should be evaluated for iodine sufficiency if their diet seems to inadequate or if they eat foods grown in a region with low iodine content. A change in composition in the diet or supplements may be called for. Iodized salt can also be a good source of iodine.

Clinical Considerations for Ensuring Adequate Iodine Intake

Although urinary iodine concentration is a sensitive indicator of recent iodine intake, laboratory tests that detect abnormal thyroid function may be more useful for diagnosing chronic iodine deficiency or excessive iodine intake, and for monitoring the effects of iodine supplementation [41]. Thyroid function testing includes measurement of serum concentrations of the following:

a. Thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]

b. Thyroxine [T4] as total T4 and free [ie, unbound] T4 [FT4]

c. Thyroglobulin [Tg]

d. Triiodothyronine [T3] as total T3 and free T3 [FT3]

Results from thyroid function studies are usually within the reference range in the presence of mild iodine insufficiency. However, in patients with euthyroidism and iodine deficiency, serum TSH levels may be normal to increased, T3 levels may be normal or slightly elevated, and T4 levels may be normal or decreased. Only in very extreme iodine deficiency does hypothyroidism develop, accompanied by an elevated serum TSH value and decreased T3 and T4 levels [41].

Dietary Considerations

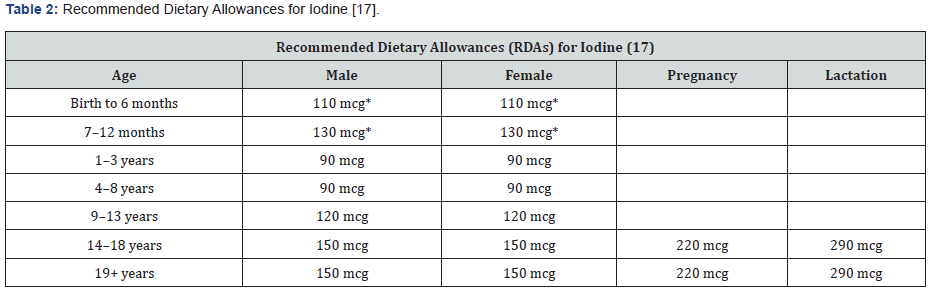

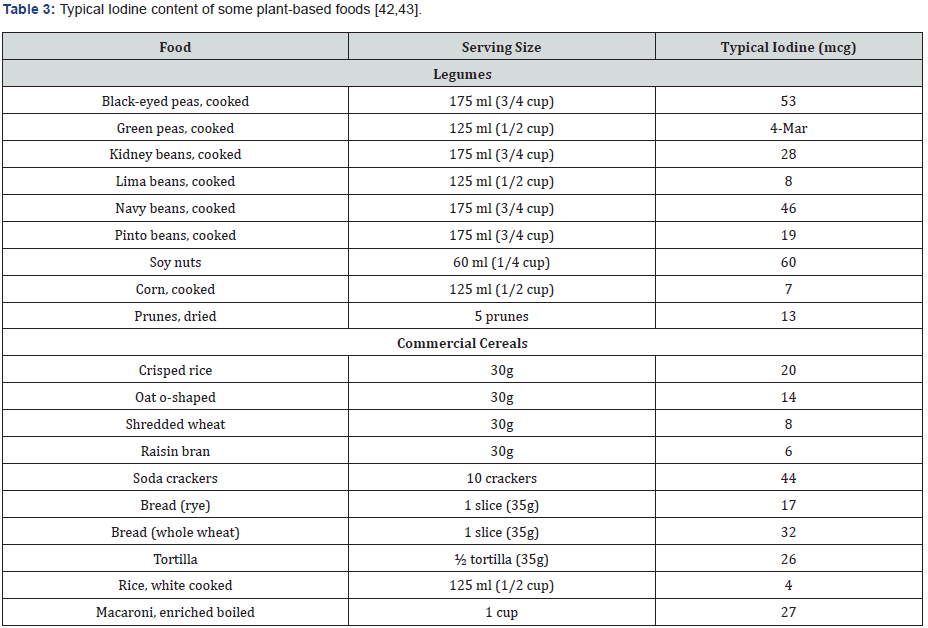

Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage naturally release a compound called goitrin when they’re hydrolyzed or broken down. Goitrin can interfere with the synthesis of thyroid hormones. However, this is usually a concern only when coupled with an iodine deficiency [17]. Importantly, heating cruciferous vegetables denatures much or all this potential goitrogenic effect [44] (Tables 2 & 3).

Soy is another potential goitrogen. However, numerous studies have found that consuming soy doesn’t cause hypothyroidism in people with adequate iodine stores [45,46,47]. Randomized controlled intervention trials in iodine- and iron-deficient populations have shown that providing iron along with iodine results in greater improvements in thyroid function and volume than providing iodine alone [48].

* Adequate Intake (AI)

Seaweeds can be very high in iodine. It is possible some seaweed dishes may exceed the tolerable upper iodine intake level of 1100 microg/d [49]. One study showed the iodine content surveyed for nori was 29.3–45.8 mg/kg, for wakame 93.9–185.1 mg/kg, and for kombu 241–4921 mg/kg. Kombu has the highest average iodine content 2523.5 mg/kg, followed by wakame [139.7 mg/kg] and nori [36.9 mg/kg] [49]. Patients who eat a lot of seaweed should counseled to consume them in moderation.

Supplements and Medication Interactions

Many multivitamin/mineral supplements contain iodine in the forms of potassium iodide or sodium iodide. Dietary supplements of iodine or iodine-containing kelp [a seaweed] are also available. One study found that potassium iodide is almost completely [96.4%] absorbed in humans [50]. Currently, it is estimated that only 51% of the types of prenatal multivitamins marketed in the United States contain iodine [51] and according to 2001–2006 NHANES data, 15% of lactating women and 20% of non-pregnant and pregnant women in the United States take a supplement containing iodine [52]. Several medications can have drug interactions with iodine supplements. Angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, such as benazepril [Lotensin®], lisinopril [Prinivil® and Zestril®], and fosinopril [Monopril®. Taking potassium iodide with ACE inhibitors can increase the risk of hyperkalemia [elevated blood levels of potassium] [53]. Taking potassium iodide with potassium-sparing diuretics, such as spironolactone [Aldactone®] and amiloride [Midamor®], can increase the risk of hyperkalemia [53].

Discussion

Millions of people in America suffer from hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, most commonly in the form of Grave’s disease or Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. While in some cases this may be due to lack of iodine, in the United States it is more likely due to obesity or an auto-immune disease. The risk of both is reduced with a plant-based diet. Reducing the risk of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism with a plant-based diet would seem especially advantageous since a plant-based diet is safe, has no adverse reactions or contraindications, and can treat and prevent several common comorbidities such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, type II diabetes and coronary artery disease. The preventative benefit of a plant-based diet might be stronger if the typical iodine intake were a bit higher. However, while those following a plant-based diet can be mildly deficient in iodine, the compensatory mechanism of increased production of TSH reduces the risk for vegans to experience thyroid dysfunction due to any lack of iodine.

References

- Rabinovitch N (2012) Urinary leukotriene E4 as a Biomarker of Exposure, Susceptibility and Risk in Asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 32: 433-445.

- Bochenek G, E Nizankowska Mogilnicka (2013) Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease: Clinical Disease and Diagnosis. Am Immunol Allergy Clin 33: 147-161.

- Laidlaw T, Boyce J (2013) Pathogenesis of Aspirin- Exacerbated Respiratory Disease and Reactions. Am Immunol Allergy Clin 33: 195-210.

- Rabinovitch N (2007) Urinary Leukotriene. E4 Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 27: 651–664.

- Higashi N, et al. (2012) Aspirin-Intolerant Asthma (AIA) Assessment Using the Urinary Biomarkers, Leukotriene E₄ (LTE₄) and Prostaglandin D₂ (PGD₂) Metabolites. Allergology International 61: 393-403.

- Wood A, et al. (2011) A systematic review of salicylates in food: estimated daily intake of a Scottish population. Mol Nutr Food Res (suppl 1): S7-S14.

- Duthie G, Wood D (2011) Natural salicylates: foods, functions and disease prevention. Food Funct 2: 515–520.

- Paterson JR, Rajeev Srivastava, Gwen J Baxter, Alan B Graham, James R Lawrence (2006) Salicylic acid content of spices and its implications. J Agric Food Che 54: 2891-2896.

- Paterson J, Gwen Baxter, James Lawrence, Garry Duthie (2006) Is there a role for dietary salicylates in health? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 65: 93-96.

- Lawrence JR, et al. (2003) Urinary excretion of salicyluric and salicylic acids by non-vegetarians, vegetarians, and patients taking low dose aspirin. J Clin Pathol 56: 651-653.

- Mitchell J, Skypala I. (2013) Aspirin and salicylate in respiratory disease. Rhinology 51: 195-205.

- Sommer D, Hoffbauer S, Au M, Sowerby LJ, Gupta MK, et al. (2015) Treatment of Aspirin Exacerbated Respiratory Disease with a Low Salicylate Diet: A Pilot Crossover Study. Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery 152(1): 42-47.

- Sommer D, Rotenberg BW, Sowerby LJ, Lee JM, Janjua A, et al. (2016) A novel treatment adjunct for aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease: the low-salicylate diet: a multicenter randomized control crossover trial. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology 6(4): 385-391.

- Sakalar EG, Muluk NB, Kar M, Cingi C (2016) Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease and current treatment modalities. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1-10.

- Nayan S, Maby A, Endam LM, Desrosiers M (2015) Dietary modifications for refractory chronic rhinosinusitis? Manioulating diet for the modulation of inflammation. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy 29(6): 170-174.

- Palacios E, Marcos Alejandro Jiménez Chobillon, Armando Roberto Castorena Maldonado, María de la Luz García Cruz, Alejandra Gamiño Pérez (2019) Correlación clínica y de concentraciones de LTE4 urinario con una dieta alta y baja en salicilatos en pacientes con enfermedad respiratoria exacerbada por aspirina. An Orl Mex octubre-diciembre 64(4): 188-201.