First Branchial Cleft Fistula - A Presentation on Two Cases and Review of Literature

Nisreen AlMusaileem1* and Imtiaz Majid Qazi2

1Department of ENT & Head and Neck surgery, Farwaniya Hospital, Kuwait

2Oto!aryngoIogy H&N surgery, alsabah medical area, Zain hospital, Kuwait

Submission: March 18, 2016; Published: March 28, 2017

*Corresponding author: Nisreen AlMusaileem and Imtiaz Majid Qazi, Department of ENT & Head and Neck surgery, Farwaniya Hospital, Kuwait, Email: musaileem@hotmail.com; drimtiazqazi@yahoo.com

How to cite this article: Nisreen A, Imtiaz M Q. First Branchial Cleft Fistula - A Presentation on Two Cases and Review of Literature. Glob J Oto 2017; 6(1): 555680. DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2017.06.555680

Introduction

First Branchial Cleft Anomalies are relatively rare congenital malformations of the head and neck. The incidences of these lesions are quite low, since they account for fewer than 8% of all Branchial Cleft Defects [1]. Due to its rarity, First Branchial Cleft anomaly is often misdiagnosed and thereby results in inappropriate management of the aforementioned disease. The delay between initial presentation and adequate treatment is around three and half years [2]. A wide range of clinical manifestations may be observed, but they are usually masked by the occurrence of moderate infections. Several authors have proposed classifications to assist appropriate diagnosis and management of these lesions. However, considerable confusion still exists in correlating these classifications with epidemiological, clinical, anatomical and histological data. The principle of management of first Branchial Cleft Anomalies is basically early diagnosis of condition to be able to plan a complete excision without facial nerve injury.

Case 1

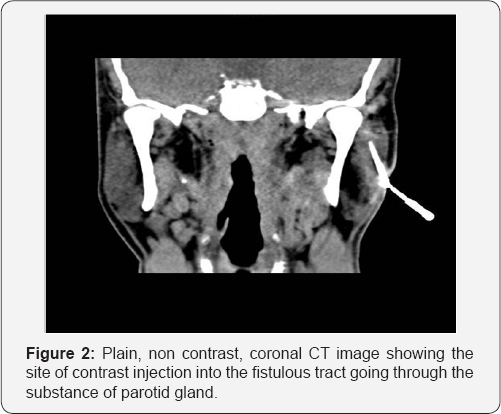

A 35 year old Bangladeshi gentleman referred to us at Zain hospital Al Sabah Medical Area, Kuwait a tertiary care referral teaching hospital, for management of recurrent discharging sinus at the left angle of mandible. The problem first appeared when he was still a young boy when he noticed a swelling in the same area. The swelling was excised when he was 10 years old. However, post operatively he noticed a discharging sinus at the site of excision, since then, he underwent several procedures, elsewhere, consisting of incision and drainage and attempts at excising it. Physical examination showed a cutaneous opening into the parotid area at the angle of mandible as shown in Figure 1. The area surrounding the cutaneous opening was scarred due to previous surgeries. Ear exam was unremarkable as was the rest of head and neck examination (Figure 2).

A provisional diagnosis of branchial cleft fistula was made and a CT fistulogram was ordered, (Figure 2). The fistulous opening was canulated and dilated, 1 cm non ionic contrast material was injected and was seen dropping out of his left ear lobule opening, a fistulous tract with cutaneous opening just above the left angle of the mandible. The fistulous tract passes through the parynchyma of superficial parotid gland to open into floor of left cartilaginous external auditory canal. The left parotid gland is otherwise normal. The diagnosis of First Branchial Cleft Fistula was confirmed.

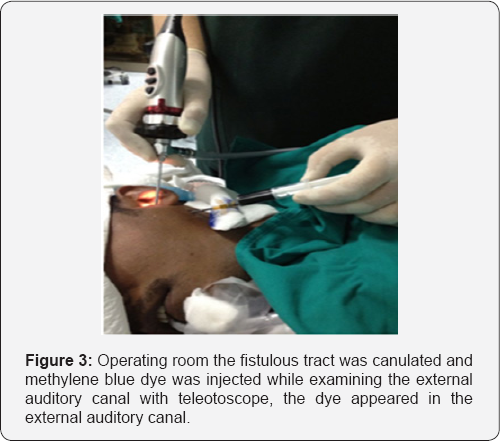

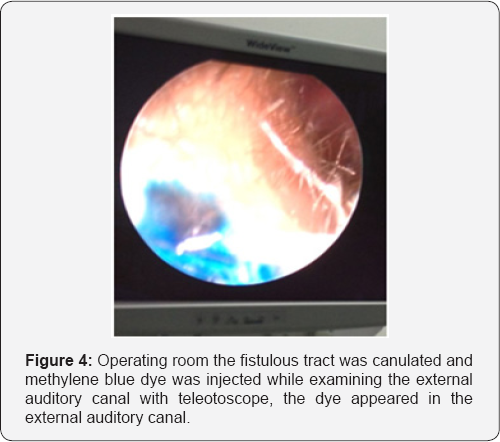

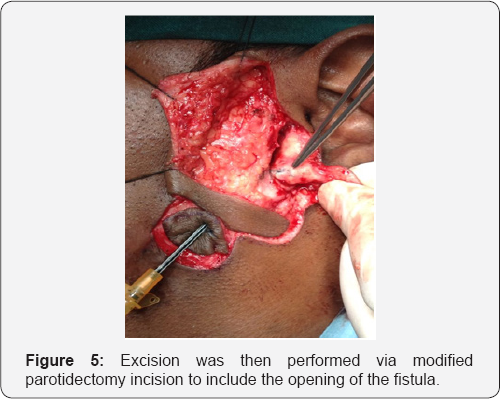

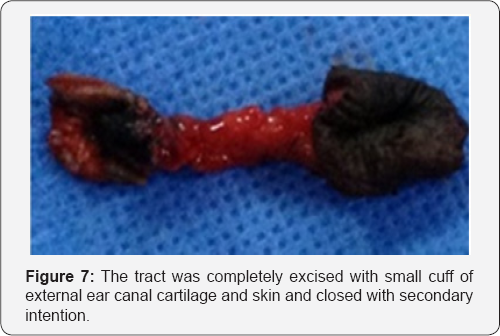

The patient was scheduled for surgery, Left superficial parotidectomy with excision of the fistulous tract. In the operating room the fistulous tract was canulated and methylene blue dye was injected while examining the external auditory canal with teleotoscope, the dye appeared in the external auditory canal (Figures 3 & 4). Excision was then performed via modified parotidectomy incision to include the opening of the fistula (Figure 5). The fistulous tract was lying medial to facial nerve (Figure 6). The aural end of the tract was lined with cartilage, while the cervical end was enmeshed in fibrous tissue. The tract was completely excised with small cuff of external ear canal cartilage and skin and closed with secondary intention (Figure 7). The facial nerve was preserved. The post operative recovery was uneventful. Histological examination of the excised fistula sent routinely confirmed the diagnosis of branchial cleft fistula.

Case 2

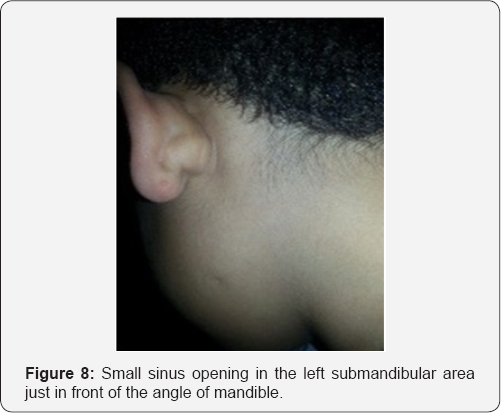

A 9 year old Kuwaiti boy, known to have congenital renal disease though no report was available to know the exact pathology, presented to our clinic with history of foul smelling discharge from left ear for 2 years that was being treated elsewhere for 1 year without any improvement. On examination, there was a swelling with punctum behind the left ear lobule and on palpation of the swelling foul smelling discharge came out from the punctum. On a closer look a small sinus opening in the left submandibular area just in front of the angle of mandible (Figure 8) was found. The external auditory canal and tympanic membrane were normal. Rest of the head and neck examination did not reveal any abnormality.

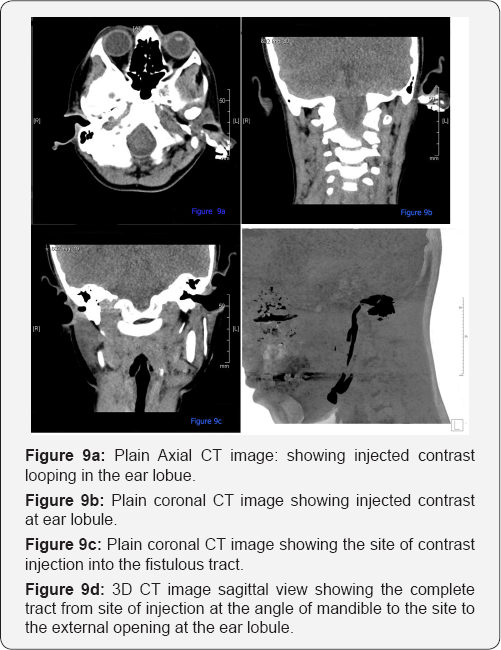

A provisional diagnosis of first branchial cleft fistula was made and a CT fistulogram was ordered, (Figure 9). The fistulous opening was canulated and dilated, 1 cm non ionic contrast material was injected which seen dropping out of his leftear lobule was opening. The CT fistulogram revealed a fistulous tract about 6 cm long, extending along the floor of the left external auditory canal, looping around left ear lobule, extending straight through left parotid gland parenchyma, and ending at left external opening at the level of the angle of the mandible. No fistulous side branches were detected. Both parotid glands appeared normal, the diagnosis of first branchial cleft fistula was confirmed. The patient was advised excision of the fistulous tract with superficial parotidectomy, however, the parents of the child opted to be treated elsewhere and the patient was lost to follow up.

Review of Literature

Incidence

First brachial cleft anomalies are rare, with only about 200 cases reported in the literature [3]. The incidence is estimated about one per million per year [4]. The anomalies account for <8% of all branchial anomalies [2]. Females patient are two times more likely to have it than male patients, and there is left side predominance [1].

Embryology

During the 4th week of human embryological development, 6 pairs of branchial arches appear which will form the future lower face and neck [58]. The maxilla as well as the parenchymal part of parotid gland developed from first branchial arch. The muscles of facial expression develop from second arch and the nerve supply of this arch is the facial nerve. At the 6th week of fetal life, the ventral portions of the first and second branchial arches fuse together.

Various theories exist to explain the formation of these anomalies. The most popular is that of external auditory canal duplication [5]. Another, proposed by oslen et al. [6] suggests that these cystic lesions may occur as a result of buried cell nest from the ventral portion of the first branchial groove. The anomaly may also result from the incomplete closure of the cleft [7]. The chance of malformations occurring nearer the ear and parotid is greater than that occurring at hyoid region, as obliteration of the cleft proceeds from ventral to dorsal [9]. Although the lesion normally has a close relationship to parotid and facial nerve, the relationship is variable, presumably because of temporal differences during development [7].

Classification

In 1971, an anatomic classification by Arnot [10] categorized first branchial cleft anomalies in to two distinct types. Type I was defined as preauricular cyst in the parotid area. Type II is a cyst or sinus in the anterior triangle of the neck extending to the external auditory canal and sometimes communicating with it.In 1972, Work [5] proposed a histological classification. Type I anomaly is a defect of ectodermal origin, arising from duplication of the membranous external auditory canal. Clinically, they appear as soft cysts lined by squamous epithelium. It can have a tract running medial and parallel to the external auditory canal, superior to facial nerve and ending in a ”CuldeSac” on a bony plate at the level of the mesotympanum.

The overlying skin is normal but accidental rupture or secondary infection may result in an intrameatal or a retroinfra auricular sinus opening. Type II defect are ectodermal and mesodermal in origin, containing skin with adnexal structures as well as cartilage. They present as a cyst, sinus, fistula or a combination. They are associated with a sinus/fistula opening in the region of sub mental triangle; extend superiorly through the parotid gland toward the floor of the external auditory canal at the level of the bonycartilaginous junction or the cartilaginous portion. A case combined with some characteristics of both type I and II anomalies was reported [11]. Volaris and Pahor [12] proposed a variant of the fistula tract extending from the ear canal to the mastoid and sternocleidomastoid muscle as type III anomaly. In the third classification, Olsen et al [6] in 1980 simply classified the defect as cyst, sinus or fistulas.

Clinical presentation

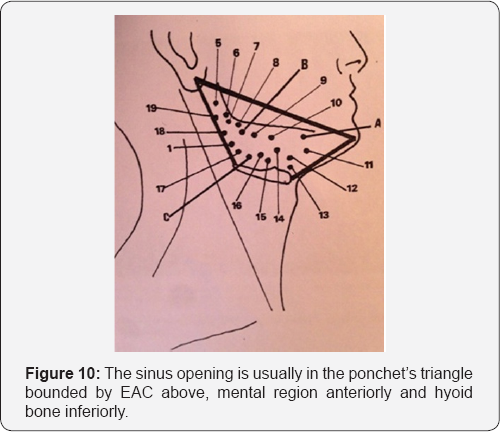

Rarity and varied presentation of the first branchial cleft anomalies have led to frequent misdiagnosis, and therefore can lead to inappropriate surgical procedures. The age of presentation of FBCA can vary from 20 days to 82 years at a mean age of 18.9 years [1]. High index of suspicion is required when encountering the following signs and symptoms to reach a proper diagnosis and management. In the neck, patients may present with repeated episodes of infection of the lesion. This may manifest itself with cystic swelling or discharge from a fistulous or sinus opening either preauriculary or postauriculary, in the cheek, or high in the neck. The sinus opening is usually in the ponchet’s triangle bounded by EAC above, mental region anteriorly and hyoid bone inferiorly [13,14] (Figure 10). The patient may also give a history of having to repeatedly undergo incision and drainage of an apparent abscess around the ear because of infective exacerbations of the lesion that has not resolved.

The most frequent otological symptom is otorrhea. Usually patient present with recurrent or chronic otorrhea in the absence of chronic otitis. A sinus or fistula opening may appear in EAC in only 44% of the patient [9] but it may not be obvious. In 10% of the patient reported by Triglia et al [9], first branchial cleft anomalies are associated with myringeal web which is an epidermal structure extends from the floor of the external auditory canal to the umbo of tympanic membrane that may originate from the extension of fistula tract. Myringeal web is only present in patient with type II anomalies and its surgical excision is not absolutely necessary. Sinus orifices and fistula tracts may be found in the middle ear, parapharyngeal space, Eustachian tube, concha cavity, or retropharyngeal space [15,16]. Bilateral ear involvement of the first branchial anomaly was reported [16]. First branchial cleft anomaly may be associated with other congenital anomaly. A few cases reported combined congenital cholesteatoma, inner ear anomalies, or some renal diseases.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of the first branchial anomaly include sebaceous cyst (creamy offensive discharge), parotid fistula (test secretion), tuberculous adenitis (associated with lymphadenopathy), congenital ductal cyst, parotid tumors, dermoid cyst, lymphangioma, cytic hygroma, lymphoma, teratoma, ectopic salivary gland or thyroid gland, retropharyngeal abscess, inclusion cysts, carotid body tumors, laryngocele, thyroglossal duct cysts, plunging ranula. Fine needle aspiration, sonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to detect the nature of a neck mass. Computed tomography is preferred to MRI due to the visualization of bony detail and better capability to determine the cystic nature of lesions. Fistula tracts to external ear canal can be found more easily under coronal sections of CT imaging. Fistulogram can be used in fistula tracts without prior infection.

Management

First is to control infection by broadspectrum antibiotics and drainage of an abscess when necessary. After infection control the treatment of choice is surgical excision with preservation of facial nerve. Relation of facial nerve to tract vary a lot, it may distribute medially, laterally or between facial nerve branches, sometimes due o the agenesis of the parotid gland it will be difficult to identify facial nerve with landmark of tragal cartilage. A type I cyst can be removed while still keeping the epidermal skin of meatus intact [8]. Work recommended marsupialisation of this cyst through the EAC [5]. For a type II, a superficial parotidectomy with wide exposure needed by modified blare or Sshape incision to totally expose the facial nerve and usually a facial nerve stimulator is needed. Skin and cartilage of the fistula or sinus opening in EAC should be removed and primary closure if possible but if more than 30% of the circumference of EAC is taken, split thickness skin graft grafting and stenting are recommended [17,18].

Ear canal packing for 2 to 4 weeks post operation was suggested for patient receiving cartilage resection to avoid ear canal stenosis [4]. If the tympanic membrane or middle ear structures are involved, reconstructive otologic surgery may be necessary [19]. Operation plans should be postponed in infants younger than 6 months old due to their underdeveloped auricular cartilage and mastoid, and rertroauricular incision proposed to avoid injury of the relatively more superficial facial nerve in children. Other management strategies such as radiotherapy, repeated inscion and drainage, sclerosing agent therapy, and varicose vein stripping have all been proposed, but some have been followed with recurrence and increased difficulties in revised operations [17]. Histopathologically, branchial cleft cyst is also named cervical lymphoepithelial cyst. The wall is almost completely composed of stratified pseudo stratified squamous epithelium. Columnar epithelium or keratinization may also be present. In addition hair follicles, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, or cartilage have been found. The epithelium is rich of follicular germinal center or broadband lymphocytes aggregation. In recurrent cases, there is a lot of mature fibrotic connective tissue. The lumen consisted of serous or colloid substance. A first branchial anomaly with malignant changes was reported [20].

Conclusion

Rarity and varied presentation of the first branchial cleft cysts have led to frequent misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. High index of suspicion is required when the sinus opening is in the poncet´s triangle. Complete excision is the main treatment. Diagnosis is by clinical correlation and histological examination of the mass.

References

- D´Souza AR, Uppal HS, De R, Zeitoun H (2002) Updating concepts of first branchial cleft defects: A litreture review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 62(2): 103109.

- Sichel JY, Halperin D, Dano I, Dangoor E (1998) Clinical update on type II first brachial cleft cysts. Laryngoscope 108(10): 15241527.

- Wettekindt C, Schondorf J, Stennert E, Jungehulsing M (2001) Duplication of the external auditory canal: a report of three cases. Int J pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 58(2): 179184.

- Arndal H, Bonding P (1996) First branchial cleft anomaly. Clin Otolaryngol 21(3): 203207.

- Work WP (1972) Newer concept of first branchial cleft defects. Laryngoscope 82(9): 15811592.

- Olsen KD, Maragos NE, Weidland LH (1980) First branchial cleft anomalies. Laryngoscope 90: 423427.

- Solares CA, Chan J, Koltai PJ (2003) Anatomical variations of facial nerve in first brachial cleft anomalies. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129(3): 351355.

- Stokroos RJ, Manni JJ (2000) The double auditory meatusrare first branchial cleft anomaly: clinical presentation and treatment. Am J Otol 21(6): 837841.

- Triglia JM, Nicolas R, Ducroz V, Koltrai PJ, Garabedian EN (1998) First branchial cleft anomalies: a study of 39 cases and a review of the litreture. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124(3): 291295.

- Arnot RS (1971) Defect of the first branchial cleft. S Afr J Surg 9(2): 9398.

- Lim LH, Hartnick CJ, willging JP: A rare case of combined type I and II first branchial sinus. J Pediatr Surg 38(10): E1213.

- Violaris NS, Pahor AL (1993) A variation of first branchial cleft anomalies. J laryngol Otol 107(7): 625626.

- Chen MF, Ueng SH, Jung SM, Chen YL, Chang KP (2006) A type II Branchial cleft cyst masquerading as an infected parotid warthin´s tumor. Chang gung Med J 29(4): 435439.

- Tham YS, Loa WK (2005) First branchial cleft anomalies have relevance in otology, more. Ann Acad Med Singapore 34(4): 335338.

- Mukherji SK, Tart RP, Slattery WH, Stinger SP, Benson MT, et al. (1993) Evaluation of the first branchial anomalies by CT and MR. J Comput Assist Tomogr 17(4): 576581.

- Shirley DM, Santos PM (1995) An unusual first branchial cleft defect. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113(6): 829832.

- Mounsey RA, Forte V, Friedberg J (1993) First branchial cleft sinuses: An analysis of current management strategies and treatment outcomes. J Otolaryngol 22(6): 457461.

- Issacson E, Marin WH (2000) First Branchial cleft cyst excision with electrophysiological facial nerve localization. Arch otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126(4): 513516.

- Tom LW, Kenealy JF, Torsiglieri AJ (1991) First branchial cleft anomalies involving the tympanic membrane and middle ear. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 105(3): 473477.

- Park SS, Karmody CS (1992) The first branchial cleft carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 118(9): 969971.