History Taking in Vertigo Patients

Lalsa Shilpa Perepa*

Clinical Audiologist, Hearing First, Canada

Submission: February 16, 2016 ; Published: March 17, 2017

*Corresponding author: Lalsa Shilpa Perepa, Clinical Audiologist, Hearing First, 1995 Weston Road Unit B, Toronto - M9N 1X2, Canada, Email: lalsashilpa.311@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Lalsa S P. History Taking in Vertigo Patients. Glob J Oto 2017; 5(2): 555660. DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2017.05.555660

Introduction

Dizziness is the most common complaint. Balance of the body is mediated by 3 systems

- Visual

- Propioreception

- Vestibular

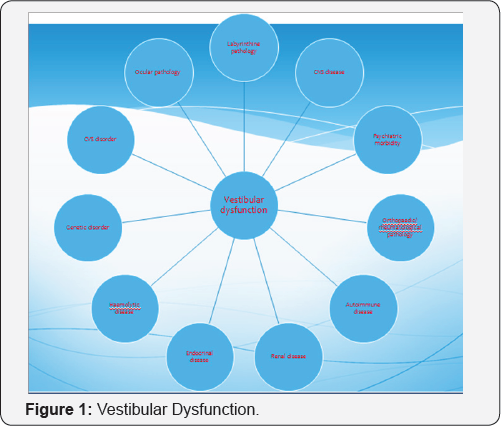

Imbalance in either of these systems leads to balance disorder which begins with dizziness (Figure 1).

How to Evaluate??

- Obtain a detailed case history.

- It is the most important diagnostic tool to understand the disorder in a broader perspective.

- A careful case history obtained is useful in differential diagnosis.

- A through case history is the most important factor in determining the cause of vertigo.

- It provides qualitative information that can be confirmed with quantitative vestibular testing.

Describe What You Are Experiencing?

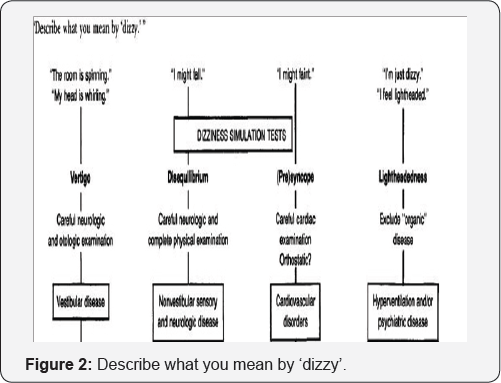

- This question really addresses the character of the dizziness the patient is experiencing

- b) It is helpful to stratify patients into two different categories of dizziness: Vertigo and Non vertigo dizziness [1-10].

- It is important to establish this dichotomy as vertigo is often due to a disorder in the vestibular system, whereas non vertigo may be related to myriad causes including cardiovascular, ocular, or systemic diseases.

- Begin with open ended questions and allow the patient to respond instead of being biased during history taking

vertigo - sensation of movement, often rotary, indicating disorder of the vestibular system

Non-vertiginous dizziness such as: imbalance, lightheadedness, syncope, faintness, and other diseases.

Imbalance may be described as dizziness, however, does not in isolation result from vestibular lesions. Imbalance may be a symptom of cerebellar dysfunction, drug toxicity, extrapyramidal disease (e.g. Parkinson disease), or other non- vestibular disorders.

Light headedness, , often described as "floating" dizziness or "wooziness" may result from medications or the multiple sensory deficits syndrome. The multiple sensory deficits syndrome results from "de-afferentation"; often patients are elderly who have visual dysfunction (e.g. macular degeneration), balance difficulty (orthopedic or extrapyramidal disease), hearing loss and peripheral neuropathy. Patients are thus effectively cut off from receiving accurate information about the orientation of the environment which often leads to "dizziness." Additionally, certain medications may produce a non-vertiginous sense of dizziness described as lightheadedness [11-15].

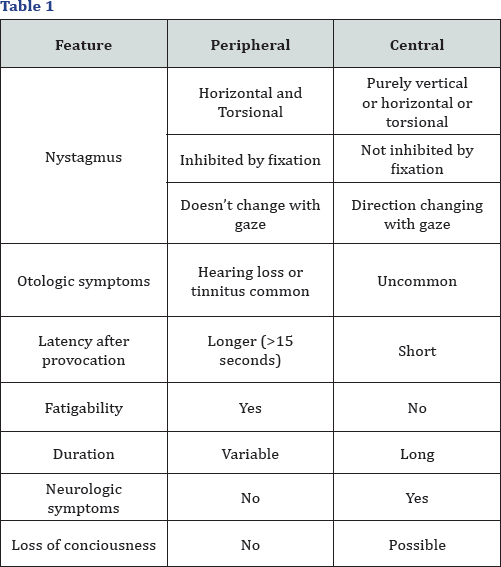

Syncope or presyncope often presents with "faint" feelings of dizziness. This sensationresults from global hypoperfusion of the brain. Cerebral hypoperfusion may result fromhypotension or arrhythmias. Orthostatic hypotension is a relatively common type ofsyncope/presyncope. This typically presents with faint feeling of dizziness after postural change, such as arising from the seated or lying position. Dehydration, certain antihypertensive medications, or autonomic failure may produce orthostatic hypotension. Other medical conditions such as endocrine diseases (especially hypothyroid) may present with non-vertiginous dizziness. Lab tests to include thyroid function and FTA/RPR are often obtained in unexplained cases. Drugs including prescription medications may also result in several types of dizziness. Patients with psychiatric disorders may describe dizziness (Figure 2) (Table 1).

How long does the dizziness last??

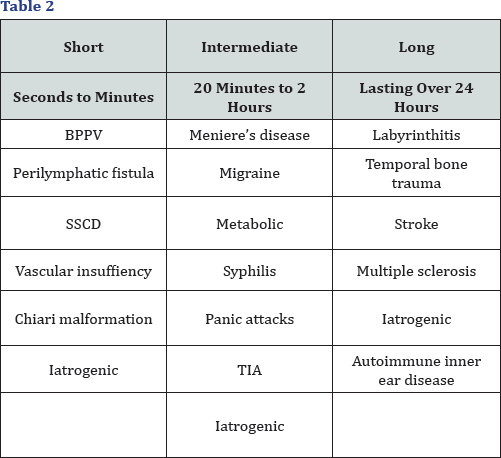

- Fleeting: Dizziness lasting less than a second probably is the result of disequilibrium due to an imbalance in peripheral vestibular inputs.

- Short-lasting: Vertigo lasting dysfunction between a few seconds and a few minutes is usually due to a peripheral vestibular dysfunction

- Intermediate: Vertigo lasting between 20 minutes and several hours can occur as a result of either central or peripheral vestibular disorders.

- Long Lasting: An isolated attack of vertigo lasting longer than a 2 to 3 hours and usually a day or days usually results from a unilateral complete permanent injury to the peripheral vestibular system

- Continuous: Continuous vertigo is a relatively uncommon but serious problem. Although the brain compensates for vertigo arising from the inner ear or vestibular nerve over several weeks, vertigo fron central dysfunction can persist longer (Table 2).

How often do you have attacks of vertigo?

- Single

- Constant

- Multiple

- Seconds

- Hours

- Days (Table 3.)

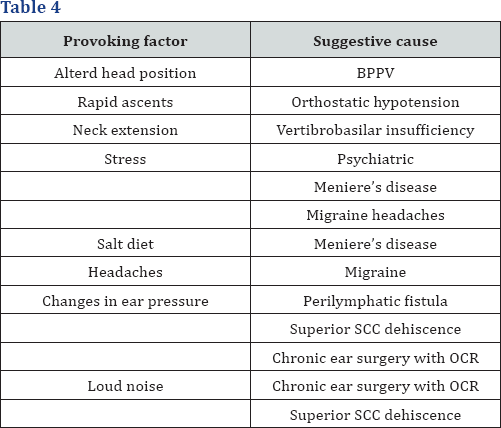

Is there anything you can do that will cause you to feel dizzy? (precipitating factors)

Although vertigo intensity may vary between individual episodes, there are often similar circumstances surrounding the onset of attacks [16-20]. Individual triggers are helpful in both short and long duration vertigo.

These are three types

- Short duration

- Long duration

- Intermediate duration (Table 4).

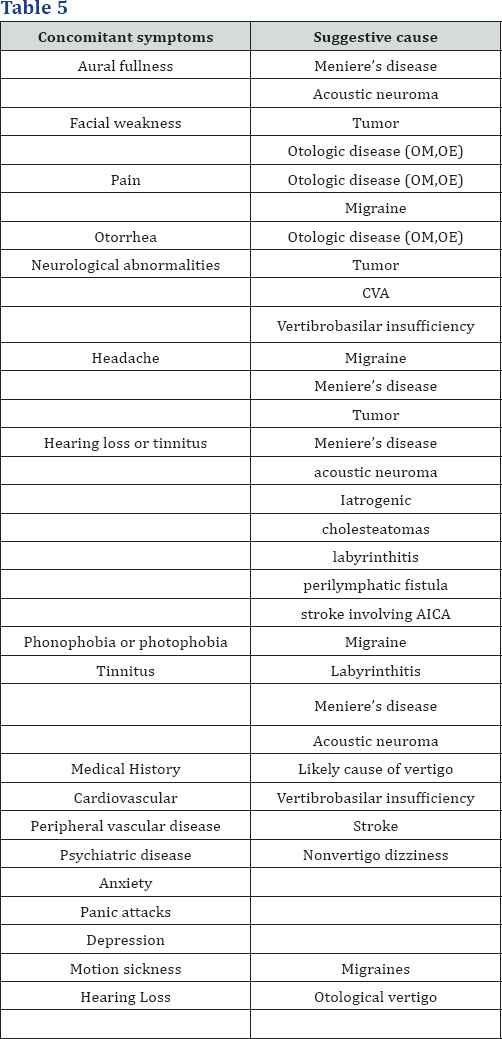

What other symptoms do you get around the time of vertigo attacks (associated symptoms)?

Concomitant symptoms including hearing loss, pain, or neurological symptoms may also help establish the diagnosis of dizziness or vertigo.

Other medical conditions may cause vertigo through direct or indirect injury to the vestibular system. It is important to determine if medical problems are contributing to or causing the patients dizziness.

Differential diagnosis based on concomitant symptoms (Table 5).

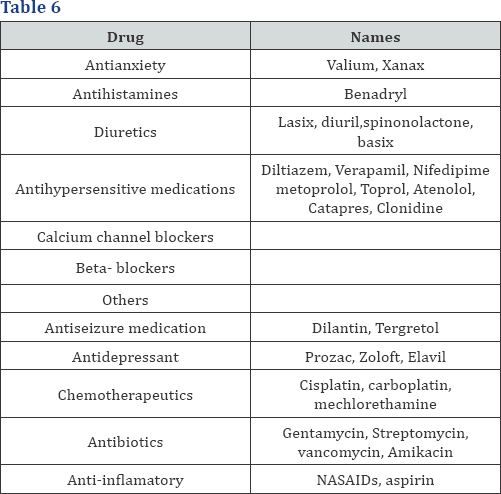

What medications are you currently taking?

- Nearly 23% of all medicines list dizziness as a possible side effect. Adverse reactions are more common in the elderly for 3 reasons:

- The elderly are prescribed more medications increasing by sheer volume the likelihood to have dizziness as a side effect.

- Reduced renal and hepatic clearance promotes increased and prolonged systemic concentrations.

- Reduced vascular reflexes reduce promote increased orthostatic symptoms (Table 6).

Other Significant Questions

Metabolic disorders

Such as uncontrolled diabetes, renal failure, hepatic failure and altered ion homostasis can induce a constant feeling of dizziness. Any abnormality in blood or serum levels can drastically alter the central nervous system's ability to function properly [20-20]. The result can often be continuos dizziness which will persist until the metabolic disorder is treated.

Psychological disorders

Psychologic disorders including hyperventilation syndrome account for the most common cause of dizziness among younger patients. Whereas symptoms typically revolve around times of heightened apprehension or anxiety, continuous symptoms are common in these patients due to continuos hyperventilation and altered CO2 concentrations.

Family history

The patients should be asked about family history of otologic and neurologic dysfunction vestibular dysfunction with a familial predisposition includes Meniere's disease, BPPV, otosclerosis,migraines, seizures and neural degenerative diseases.

References

- Brandt T, Strupp M (2005) General vestibular testing. Clin Neurophysiol 116(2): 406-426.

- Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt D, Bergfeldt L, Blanc JJ, et al. (2001) Task Force Report: Guidelines on Management (Diagnosis and Treatment) of Syncope. Eur Heart J 22(15): 1256-1306.

- Desmond Alan (2004) Vestibular Function: Evaluation and Treatment. Thieme Medical Publishers, INC, New York, USA, pp. 65111.

- Dieterich M, Brandt T (1993) Ocular torsion and tilt of the subjective visual vertical are sensitive brainstem signs. Ann Neurol 33(3): 292299.

- (1994) Dizziness: procedure improves care for a common complaint. Mayo Clin Health Lett 12: 1-3.

- Drachman DA, Hart CW (1972) An approach to the dizzy patient. Neurology 22(4): 323-334 .

- Friedmann G (1970) The judgment of the visual vertical and horizontal with peripheral and central vestibular lesions. Brain 93(2): 313-328.

- Furman JM, Cass SP (1999) Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med 341(3-4): 1590-1596.

- Fife TD, Tusa RJ, Furman JM, Zee DS, Frohman E, et al. (2000) Assessment: vestibular testing techniques in adults and children: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 55(10): 1431-1441.

- Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS (1999) Clinical testing of otolith function. Ann NY Acad Sci 871: 221-230.

- Hazarika P, Nayak DR, Balakrishnan R. Ear Nose Throat Head & Neck Surgery: Clinical and Practical (3ri edn). CBS publishing and dristribution.

- Hirsch C (1940) A new labyrinthine reaction: the waltzing test. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 49: 232-238.

- Jacobson GP, Newman CW, Kartush JM (1993) Handbook of Balance Function Testing. Singular Publishing Group, San Diego, USA.

- Jacobson GP, Shepard NT (Eds.), Balance function assessment and management. Plural, San Diego, CA, USA, p. 63-97.

- Jongkee LB, Maas J, Philipszoon A (1962) Clinical nystagmography: a detailed study of electronystagmography in 341 patients with vertigo. Pract Otorhinolaryngol (Basel) 24: 65-93.

- Lanska DJ, Remler B (1997) Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo: classic descriptions, origins of the provocative positioning technique, and conceptual developments. Neurology 48(5): 1167-1177.

- Lornes Parnes, Sumit K Agrawal, Jason Atlas (2003) Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ 169(7): 681-693.

- Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El-Kashlan H, et al. (2008) Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 156(3�x005F;suppl): S1-S47.

- Shepard NT, Telian SA (1996) Practical Management of the Balance Disorder Patient. Singular Publishing Group, San Diego, USA.

- Tabak S, Collewijn H, Boumans LJ (1997) Deviation of the subjective vertical in long-standing unilateral vestibular loss. Acta Otolaryngologica 117(1): 1-6.

- Vereeck L, Wuyts F, Truijen S, Van de Heyning P (2008) Clinical assessment of balance: normative data and gender and age effects. Int J Audiol 47(2): 67-75.

- Vibert D, Hausler R (2000) Long-term evolution of subjective visual vertical after vestibular neurectomy and labyrinthectomy. Acta Otolaryngol 120(5): 620-622.

- Von Brevern M, Schmidt T, Schonfeld U, Lempert T, Clarke AH (2005) Utricular dysfunction in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol 27(1): 92-96.

- Wetzig J, Hofstetter-Degen K, Maurer J, von Baumgarten R (1992) Clinical verification of a unilateral otolith test. Acta Astronaut 27: 19

- Wolfe (1993) Head-upright Tilt Test: American Fam. Physician 149158.

- Wolf M, Hertanu T, Novikov I, Kronenberg J (1999) Epley's manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a prospective study. Clin Otolaryngol 24(1): 43-46.

- Wuyts FL, Hoppenhrouwers M, Pauwels G, Van de Heyning P (2002) Unilateral otolith function testing - is the utricular function additive. J Vestib Res 11: 304.