Pediatric Airway Emergency Referrals Requiring Surgical Management: A Five-year Experience at King Abdulaziz University

Rafat Sindi*1, Khalil Sendi1, Shatha Albokhari2, Mahmood Alreefi1

1Department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, King AbdulAziz University, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Pediatrics, King AbdulAziz University, Saudi Arabia

Submission: November 27, 2016; Published: December 13, 2016;

*Corresponding author: Rafat Sadaqa Sindi, Department of ORL-HNS, Faculty of Medicine, P.O Box 80270, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia.

How to cite this article: Rafat S, Khalil S, Shatha A, Mahmood A. Pediatric Airway Emergency Referrals Requiring Surgical Management: A Five-year Experience at King Abdulaziz University. 2016; 2(4): 555592. DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2016.02.555592

Abstract

Introduction: Pediatric airway emergencies are uncommon; however they are challenging to manage. The study aimed to describe our experience in the surgical management of pediatric airway emergencies.

Methods: This was a retrospective chart review of the medical records of pediatric patients at the Department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery of King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH) between November 2008 and November 2013. We recorded the age, gender, cause of referral, confirmed diagnosis, genetic and other systematic disorders, prematurity status, type of surgery performed, and the need for further surgical intervention for all patients included in this study. The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

Results: We included 37 patients aged 45 days to 10 years. In most cases, patients were referred for failed extubation, followed by stridor and respiratory distress. Laryngomalacia was the most frequently diagnosed condition. Less common diagnoses included presence of a thick mucus plug, tuberculosis, supraglottic adhesions, and bronchial foreign body. Nearly half of the referred patients had neurological disorders; 40.5% and 27.0% of the patients had respiratory and cardiovascular disorders, respectively. Bronchoscopy was the most frequently performed surgery, followed by tracheostomy. Less than half of the patients (45.9%) needed further surgical intervention.

Conclusion: Pediatric airway emergencies referral is uncommon. Failure to extubation is the most common etiolgical factor and bronchoscopy the most common performed procedure. Majority of these patients are premature, have other systemic disorders and they usually required multiple surgeries during follow up period

Keywords: Airway emergency; Bronchoscopy; Pediatrics; Surgical management; Tracheostomy

Introduction

Pediatric emergencies account for only 2-10% of all medical emergencies [1]. In addition, pediatric airway disorders are, fortunately, not commonly encountered. The management of pediatric airway disorders is, however, challenging owing to the anatomic differences between children and adults, which predispose children to acute airway compromise [2]. Thus, pediatric cases of airway disorder that are referred to an otolaryngologist on an emergency bases indicate the seriousness of the condition and the need for fast intervention, since poor or inadequate management might lead to an unfavorable outcome, including serious injury and death. Pediaricians should recognize an obstructive respiratory emergency, as prompt recognition of an airway compromise and appropriate, timely intervention determine the best possible outcome [2]. In general, if rapid reversal of an impending airway complication is impossible, then the best approach is to secure the airways temporarily.

However, when an unexpected difficult airway occurs in a child, a Pediatrician should rapidly refer the patient for specialized care, and it is critical to not persist with repeated attempts since this can cause trauma to the upper airway, edema, and bleeding [3]. Emergency airway referrals to the Otorhinolaryngology department are common. Surgical management options are enormous and choosing the correct one can help the patient and prevent the occurrence of life-threatening complications. KAUH manages many cases of pediatric airway emergencies and it is important to have knowledge of how these cases are managed, as it will help to establish an idea of the common pathologies that are commonly encountered and the outcomes. Thus, the aim of this study was to describe our experience in the surgical management of pediatric airway emergencies.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed of the medical records of pediatric patients who were followed up and treated at the Department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery of KAUH between November 2008 and November 2013. We included all children who were referred from Pediatric department for surgical management of an airway emergency. All non-pediatric cases of airway emergencies and pediatric airway emergencies that required non-surgical treatment were excluded. The Biomedical Ethics Committee of King Abdulaziz University granted approval to conduct the study.

For all patients included in the study, the following data were recorded: age, gender, cause of referral, confirmed diagnosis, genetic and other systematic disorders, prematurity status, type of surgery performed, and the need for further surgical intervention. There is no fixed protocol for the management of pediatric airway emergencies at our department, as treatment depends on several factors, including the etiology of airway disorder, the patient’s status, and the presence of other comorbidities.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, version 20, 2011). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Results are expressed in frequency (percent).

Results

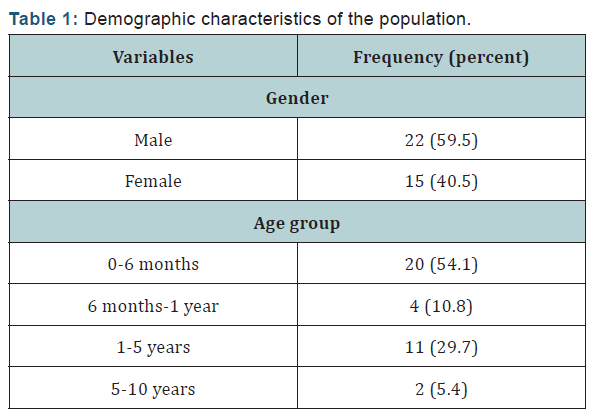

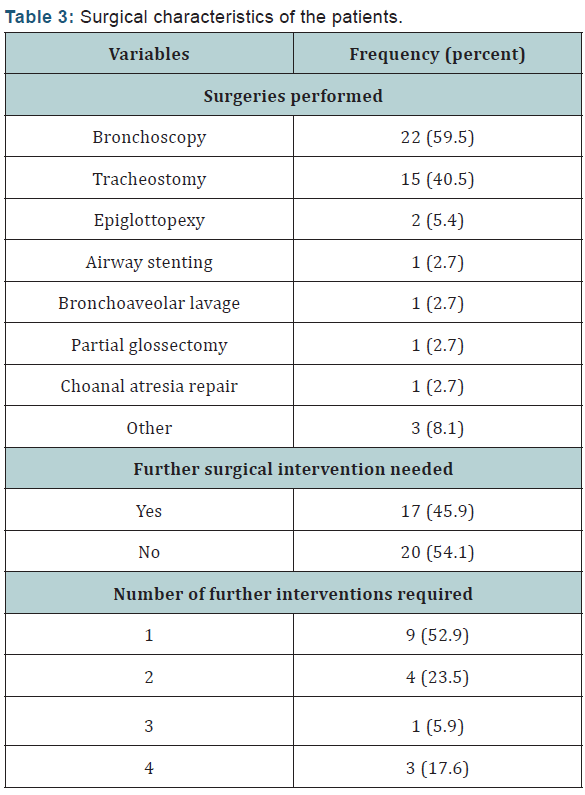

We included 37 patients aged 45 days to 10 years. Over half of the referred cases were infants less than six months old. Males comprised 59.5% of the sample (Table 1). In most cases, patients were referred for failed extubation, followed by stridor and respiratory distress (Table 2). Laryngomalacia was the most frequently diagnosed condition. Less common diagnoses included presence of a thick mucus plug, tuberculosis, supraglottic adhesions, and bronchial foreign body. Nearly half of the referred patients had neurological disorders (Table 3); 40.5% and 27.0% of the patients had respiratory and cardiovascular disorders, respectively. Premature patients constituted less than one quarter of the sample. Few patients (n= 12, 32.4%) had genetic disorders, of which 4 (33.3) had Down’s syndrome. Bronchoscopy was the most frequently performed surgery, followed by tracheostomy (Table 3). Less than half of the patients (45.9%) needed further surgical intervention; 59.9% needed one more surgery, 23.5% needed two, 5.9% needed three, and 17.6% needed four surgeries.

Discussion

This retrospective chart review sought to describe our experience with the management of pediatric airway emergencies at the Otorhinolaryngology Department of KAUH. Our analysis shows that most cases of pediatric respiratory emergency were referred for failed extubation, followed by stridor, and respiratory distress. The frequency of extubation failure in our study was 64.9%. The rates of extubation failure vary slightly in the literature. According to one report [4], extubation failure occurs in 10 to 20% of patients, and it is associated with adverse outcomes, including mortality rates of up to 25-50%. In another report [5], the authors reported that the rate of extubation failure varies from 2% to 20% depending on the patient population under consideration. However, the differences observed in the extubation failure rates may be explained by the authors’ definition of extubation failure.

While we considered extubation failure to mean the failure to be extubated, the other authors defined extubation failure as the need to re-intubate and mechanically ventilate the patient after prior successful weaning from respiratory ventilation and extubation. Stridor was the second most common reason for referral in our study, reported in 27.0% of the cases in our study. In the intensive care setting, the prevalence of post-extubation stridor ranges between 6 and 37% [6], and factors, such as female gender, elevated Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, low Glasgow Coma Scale score, and long intubation period have been correlated with the occurrence of post extubation stridor [7-10]. Respiratory distress, which was the main reason for referral in 8.1% of the cases in our study, occurs relatively infrequently in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

The reported incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients admitted to the PICU varies between 1.4 and 3.9% [11-14]. However, the mortality rates associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome vary considerably between studies, with rates reported at 26% to as high as 61% [12,15- 17]. Although our study highlights the most common causes of pediatric airway referrals at our institution, the findings must be interpreted in the light of its limitations. First, our study was limited by its small size. This precluded us from making relevant comparisons with those of other others. Second, the lack of detailed computerized notes post-surgery did not permit us to record additional details regarding patients’ recovery after surgical intervention. In addition, the exact cause of extubation failure was not documented in patients’ files.

In the current study, bronchoscopy was the most frequently performed surgery, followed by tracheostomy. The average length of stay was 2 weeks and 12.5% stayed for 2month post procedures with regards to other issues related to original diagnosis, From the patients included in the study 6.25% had tracheostomy malfunction, 6.25% complicated by emphysema ended by removal of the tracheostomy, 12.5% were complicated by chest infection ( gram negative bacilli in respiratory culture) in which one was admitted to PICU, mortality was reported in 25% due to unknown causes (lack of documentation) and 50% of the patients lost follow up with both pediatric and ENT teams.

Conclusion

Pediatric airway emergencies referral is uncommon. Failure to extubation is the most common etiolgical factor and bronchoscopy the most common performed procedure. Majority of these patients are premature, have other systemic disorders and they usually required multiple surgeries during follow up period.

References

- Bernhard M, Hilger T, Sikinger M (2006) Patientenspektrum im -Notarztdienst. Was hat sich in den letzten 20 Jahren geändert? Anaesthesist 55: 1157-1165.

- Rotta AT, Wiryawan B (2003) Respiratory emergencies in children. Respir Care 48(3): 248-258; discussion 258-260.

- Stackhouse RA, Infasino A. Airway Management. In: Basics of Anesthesia. (6th edn). Edited by Miller RD, Pardo M. Elsevier: Philadelphia, US, pp. 219-251.

- Thille AW, Richard JC, Brochard L (2013) The decision to extubate in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187(12): 1294-1302.

- Epstein SK (2000) Endotracheal extubation. Respir Care Clin N Am 6(2): 321-360,vi.

- Lee CH, Peng MJ, Wu CL (2007) Dexamethasone to prevent postextubation airway obstruction in adults: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Crit Care 11(4): R72.

- Jaber S, Chanques G, Matecki S, Ramonatxo M, Vergne C, et al. (2003) Postextubation stridor in intensive care unit patients. Risk factors evaluation and importance of the cuff-leak test. Intensive Care Med 29(1): 69-74.

- Erginel S, Ucgun I, Yildirim H, Metintas M, Parspour S (2005) High body mass index and long duration of intubation increase postextubation stridor in patients with mechanical ventilation. Tohoku J Exp Med 207(2): 125-132.

- Cheng KC, Hou CC, Huang HC, Lin SC, Zhang H (2006) Intravenous injection of methylprednisolone reduces the incidence of postextubation stridor in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med 34(5): 1345-1350.

- François B, Bellisant E, Gissot V, Desachy S, Boulain T, et al. (2007) 12-h pretreatment with methylprednisolone versus placebo for prevention of postextubation laryngeal oedema: a randomized double-blind trial. Lancet 369(9567): 1083-1089.

- Bindl L, Dresbach K, Lentze MJ (2005) Incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome in German children and adolescents: a populationbased study. Crit Care Med 33(1): 209 -212.

- Yu WL, Lu ZJ, Wang Y, Shi LP, Kuang FW, et al. (2009) Collaborative Study Group of Pediatric Respiratory Failure. The epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome in pediatric intensive care units in China. Intensive Care Med 35(1): 136-143.

- Kneyber MC, Brouwers AG, Caris JA, Chedamni S, Plötz FB (2008) Acute respiratory distress syndrome: is it under recognized in the pediatric intensive care unit? Intensive Care Med 34(4): 751-754.

- López-Fernández Y, Azagra AM, de la Oliva P, Modesto V, Sánchez JI, et al. (2012) Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Epidemiology and Natural History (PED-ALIEN) Network. Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Epidemiology and Natural History study: Incidence and outcome of the acute respiratory distress syndrome in children. Crit Care Med 40(12): 3238-3245.

- Farias JA, Frutos F, Esteban A, Flores JC, Retta A, et al. (2004) What is the daily practice of mechanical ventilation in pediatric intensive care units? A multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 30(5): 918-925.

- Flori HR, Glidden DV, Rutherford GW, Matthay MA (2005) Pediatric acute lung injury. Prospective evaluation of risk factors associated with mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171(9): 995-1001.

- Erickson S, Schibler A, Numa A, Nuthall G, Yung M, et al. (2007) Acute lung injury in pediatric intensive care in Australia and New Zealanda prospective, multicenter, observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 8(4): 317-323.