Disseminated Amyloidosis in Head and Neck - Literature Review and Discussion of an Unusual Case

José Gabriel Miranda da Paixão1, Terence Pires de Farias*2, Theresinha Carvalho da Fonseca3, Juliana Fernades de Oliveira1, Arli Regina Lopes de Moraes1, Paulo José de Cavalcanti Siebra1 and Juliana Maria de Almeida Vital1

1Department of Head and Neck Surgery, Brazilian National Cancer Institute, South America

2Department of Head and Neck Surgery, Pontifícia Universidade Católica of Rio de Janeiro, South America

3Adjunct researcher of Brazilian National Cancer Institute, MsC and PhD on Oncology for Brazilian National Cancer Institute, Attending surgeon of Brazilian National Cancer Institute, Professor of Head and Neck Surgery in Pontifícia Universidade Católica of Rio de Janeiro, South America

Submission: July 26, 2016; Published: August 16, 2016

*Corresponding author: Terence Pires De Farias, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, Rua Sorocaba 477, Ap.1201, Botafogo, Rio De Janeiro- Rj, Zip Code: 22271110, South America, AP.1201, Botafogo, Rio De Janeiro – Rj, Zip Code: 22271110;Email:Terencefarias@yahoo.Com.Br

How to cite this article: José Gabriel Md P, Terence P dF, Theresinha C dF, Juliana Fd O, Arli Regina L dM, et al. Disseminated Amyloidosis in Head and Neck - Literature Review and Discussion of an Unusual Case.Glob J Otolaryngol. 2016; 1(5): 555574. 10.19080/GJO.2016.01.555574

Abstract

Primary amyloidosis of head and neck is an extremely rare event and there are few cases reported in the literature. Amyloidosis is a group of diseases that have as etiology the extracellular proteins deposition in many organs, causing architectural and functional damage to them. This article´s objective is to report a case of primary amyloidosis localized in skin, tongue, parotid and upper airways simultaneously in one patient and do a literature review on the topic. Patient W.K.Y. 72 years-old, from China, living in Brazil for 6 months, come out with vesicles in the head and neck about one year ago. The disease had been spreading to face and neck skin as well as lips, oral mucosa and tongue. Because of oral feeding impairment and dyspnoea, the patient was taken to an emergency service, where clinical investigation started. As previous treatment, It was reported the use of Chinese medicine, acupuncture and herbs. Patient had no diabetes, hypertension, Alzheimer’s disease or nephropathy. Also, he had no family history of any degenerative or infectious disease. Patient diagnosis was: primary amyloidosis with secondary rheumatoid component. For treatment, a prednisolone pulse therapy associated with colchicine was elected, causing regression edema of tongue, suprahyoid region, lips and parotid glands, likewise about 50% of skin neck vesicles disappeared Head and neck Amyloidosis occurs in 19% of cases and may affect the skin, ear, nasal cavity, oral cavity, parotid, pharynx and larynx. Larynx is the most commonly affected organ in this region, accounting for the largest number of case reports and case series in the literature, with treatment and well-established management. The diagnosis is made based on histopathologycal examination and biochemical characterization of amyloid type. The treatment is based on the surgical resection with variable recurrence rates, according to affected organ.

Keywords: Cochlear implants; Hearing aids; Hearing preservation; Electroacoustic stimulation; Deafness; Bilateral deafness

Abbreviations: PET-CT: Positron Emission Computed Tomography; AL: Light Chain Amyloidosis; AA: Amyloid A Protein; TTR: Transthyretin; ATTR: Amyloid Derived from TTR; Aβ2M: Amyloid Derived from β2- microglobulin

Introduction

Primary amyloidosis of head and neck is an extremely rare event and there are few cases reported in the literature [1,2]. In this universe, there is preferential involvement of upper airways, being the larynx the most affected organ [3,4]. Other affected sites are: skin [5,6], oral cavity [7,8], nasal cavity [9,10], pharynx [11], parotid gland [2] and ear [12,13]. No reports on multiple sites involvement in head and neck were found in literature review. Amyloidosis is a group of diseases that have as etiology the extracellular proteins deposition in many organs, causing architectural and functional damage to them [14]. Although this mechanism is not fully understood, any human plasma precursor protein may undergo malformations and self-aggregate, originating deposits [15]. This entity can be classified according to their clinical manifestations (as systemic or localized), etiology (primary or secondary) and biochemical expression (there are over 25 amyloidosis subtypes described) [14,16,17]. In this article, the focus is on localized primary amyloidosis in head and neck.

As a rare event, most of the information available in the literature are in reviews [8,15], case reports [5-7] or case series [16,18]. Though the pathophysiology of this disease is not well understood, it is suggested that head and neck amyloidosis is linked to the light chain subtype (AL) [15,16]. The larynx is the most affected organ, but these cases are rarely related to systemic disease. Considering only this organ, more often sites of amiloid deposits are (in decreasing order of involvement): ventricular fold, aryepiglottic fold and subglottis [19]. Tongue is also often affected, but is most related to systemic disease with associated renal and/or heart manifestations [8,20], therefore a secondary amyloidosis. Primary localized tongue amyloidosis is rare [15].

Given the rarity of these cases, recognition, understanding and propper evaluation are important to seek a better treatment. This article´s objective is to report a case of primary amyloidosis localized in skin, tongue, parotid and upper airways simultaneously in one patient and do a literature review on the topic.

Case Presentation

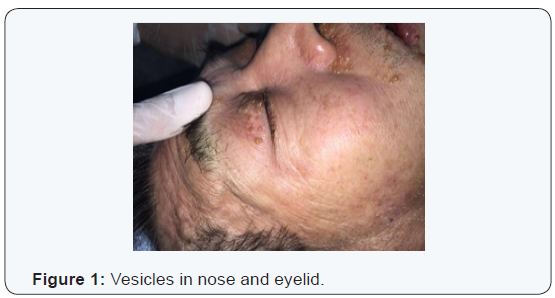

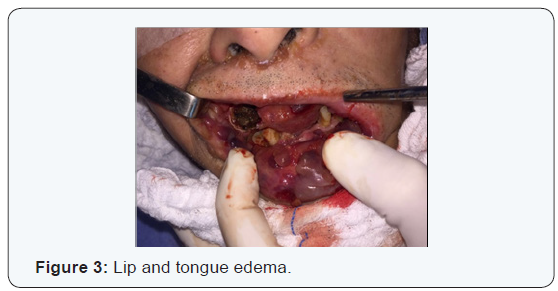

W.K.Y. 72 years-old, from China, living in Brazil for 6 months, come out with vesicles in the head and neck about one year ago. The disease had been spreading to face and neck skin as well as lips, oral mucosa and tongue. Because of oral feeding impairment and dyspnoea, the patient was taken to an emergency service, where clinical investigation started. As previous treatment, It was reported the use of Chinese medicine, acupuncture and herbs. Patient had no diabetes, hypertension, Alzheimer’s disease or nephropathy. Also, he had no family history of any degenerative or infectious disease. The only comorbidity found was rheumatoid arthritis clinically controlled with irregular medical treatment and alternative medicine, for about 10 years. Physical examination revealed: vesicles on the eyelids, facial skin, nose, upper lip, both ears and disseminated by neck skin. An edema affecting the whole oral tongue and its base, suprahyoid muscles, upper and lower lips mucosa. There was also billateral parotid enlargement, however no obvious tumors (Figures 1-4).

At initial evaluation, differential diagnosis suggested were: leprosy, tuberculosis, paracococidioidomycosis and HIV, as infectious processes; Amyloidosis and sarcoidosis, as deposit diseases; Neoplastic disease, as tongue squamous cell carcinoma associated with opportunistic infectious disease. Due to intense dyspnoea, an emergency procedure was performed: endotracheal bronchoscopy assisted intubation (in which lesions in the pharynx, larynx and thickening of tracheal mucosa were diagnosed, tissue sample and a bronchial lavage were collected) and tracheostomy.

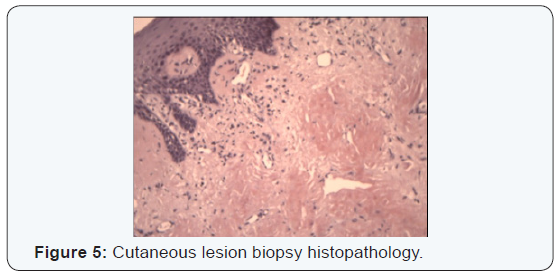

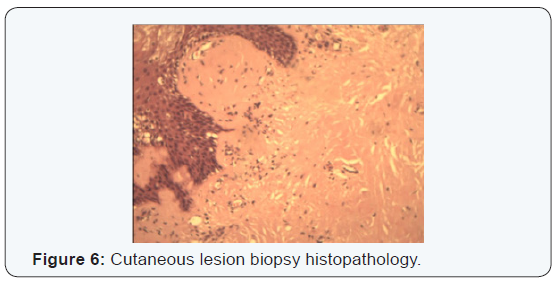

A bilateral Superficial parotidectomy with conservation of both facial nerves, suprahyoid muscles and base of the tongue biopsies through a suprahyoid access, as well as oral tongue, lip mucosa and multiple skin biopsies. Also a nasogastric feeding tube was placed. The frozen section was not conclusive, but examination using the congo red stain was positive in all biopsied sites (Figures 5 & 6).

There was no signal of any amyloidosis foci in other body regions. Koch’s bacillus, Paracoccidioidis brasiliensis, Hansen bacillus, various fungi, gram positive and negative bacteria, and anaerobes cultures were, all of them, negative. Also, bronchial lavage were sterile. The admissional chest x-ray showed discrete left pleural effusion (without identified germs) and laboratory tests had normal red blood cells count without coagulation disorders, biochemistry without alterations, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate slightly elevated, normal urinalysis, negative urine cultures and negative blood dosage of heavy metals.

A PET-CT was performed to rule out a primary malignancy, which was negative. A myelogram and Bence Jones proteins dosage both negative, excluding multiple myeloma hypothesis. An echocardiogram showed no heart vegetations as well as the ejection fractions were compatible with age. Moreover, renal ultrasonography, creatinine clearance and 24-hour proteinuria were normal, showing no renal function impairment. Amyloid protein light chain Ig AL dosage in serum was positive. The AA amyloid and serum protein A were negative, the same happening with AI apolipoprotein and AII apolipoprotein, thus discarding familiar amyloidosis. Immunohistochemistry was not necessary to confirm histopathologycal diagnosis.

There fore, patient diagnosis was: primary amyloidosis with secondary rheumatoid component. For treatment, a prednisolone pulse therapy associated with colchicine was elected, causing regression of edema in tongue, suprahyoid region, lips and parotid glands, likewise about 50% of skin neck vesicles disappeared. However, laryngeal and tracheal mucosa edema did not disappear, making decannulation impossible. Between emergency admission, hospital discharge and the last outpatient consultation, total treatment time was 45 days. Combination with melphalan and if necessary a plasmapheresis were being scheduled, but the patient preferred to return to China.

Discussion/Literature Review

Extracellular insoluble proteins deposits was observed in 1842 by Rokitansky, however the term “amyloid” to describe this phenomenon was first applied by Virchow in 1851 [14] based on a term coined to name a normal constituent of vegetal cell [21,22]. Currently, amyloid refers to an extracellular deposition of various proteins that have different primary structures, but share similar characteristics such as (I) forms an amorphous hyaline material in light microscopy after haematoxylin-eosin staining, (II) orange-green birefringence in polarized light microscope after Congo Red staining and (III) amyloid fibrils composition [23-25].

Extracellular amyloid deposit in tissues as a result of a change in protein synthesis results in a condition called Amyloidosis [22]. Amyloidosis is a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by fibrillar proteins deposition in tissue causing different clinical syndromes depending on the type of amyloid, location and amount of amyloid deposition [23]. Its etiology has a common route, in which precursor proteins become amyloid fibrils under various pathological molecular environments. Although the exact causes of these change are not fully understood [14,24], genesis of amyloid fibrils may be related to the inherent instability of a native protein, with the overproduction of a native protein or with the production of an abnormal protein, which generate proper conditions for misfolding [26].

The differentiation between primary and secondary amyloidosis, as well as its relationship with inflammatory, infectious diseases and multiple myeloma was made through analysis and comparison of case reports during early twentieth century [21], but the idea of one single amyloid substance was prevailing. In the 1970’s, development of amyloid fibrils solubilizing methods made possible to understand that each type of amyloid contains a different form of amyloid fibrils derived from a specific precursor protein, which has little or no relationship between each other [26]. This fact contributed to constant revision and expansion of amyloid classification [27-31]. There are 31 types of proteins that have been classified as components of amyloid fibrils, but there are still some that are being biochemically characterized [14,22,24], for example the one that is common in parathyroid deposits [32]. There is some degree of confusion in the literature regarding nomenclature of amyloid fibrils and amyloidosis as disease. According to the last nomenclature guideline [22], amyloid protein is designated by the letter “A” which is followed by a suffix corresponding to the precursor protein, such as “L” for the light chains derived immunoglobulin. AL is the protein that causes the disease, whereas disease is AL amyloidosis which has different clinical manifestations according to the affected organ [22,33].

Clinically, amyloidosis is classified as localized or systemic and primary or secondary [14,16,17,33,34]. There are four major types of amyloidosis: AL, AA, ATTR, and Aβ2M. AL amyloidosis is the most common and can be primary / idiopathic or may be related to a low degree clonal proliferation, such as multiple myeloma. The light chains of kappa and lambda immunoglobulin are the precusors of this type of amyloid deposit and it has diverse clinical manifestations. The second most common is AA amyloidosis, which is related to infectious processes (such as tuberculosis and leprosy) and chronic inflammation (such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease). This is because its precursor protein is an acute phase protein serum amyloid A (SAA). As clinical manifestations several degrees of renal failure is observed in 90% of cases. The third most important type is the ATTR amyloidosis, and its precursor protein is transthyretin (TTR), which has about 100 described mutations, among the most prevalent is TTR-Met30. There is a non-familiar form in which by an unknown mechanism wildtype TTR serve as amyloid precursor. In this type, predominant clinical manifestations are peripheral and autonomic neuropathy. The fourth type is the Aβ2M amyloidosis, caused by chronic high levels of β2-microglobulin in serum of end stage kidney disease patients. Because it is not properly removed from serum, it serves as amyloid precursor and deposits occurs predominantly in osteoarticular tissues, with carpal tunnel syndrome and shoulder pain among earliest symptoms, followed by periarticular cysts, pathological fractures and destructive spondyloarthropathy.

Very little information on Amyloidosis incidence and prevalence was lately published [33,35] and data from a classic study of the 1990’s are still used as reference [36]. This is indicates how rare is this disease. Although such data was based on nomenclatures and classifications that are outdated and considering the changes in diagnostic criteria and methods since then, for the most common amyloidosis form Kyle et al. [36] are still reliable, mainly due to its judicious study method. In this study, it is estimated that AL amyloidosis incidence is 8.9 cases/ one million people a year, the mean age of incidence was 75 years, with male predominance and it was not related to occupation or socioeconomic status. In recent surveys [35,37], AL amyloidosis annual incidence was similar, as the number of women with AA amyloidosis are higher in comparison with AL amyloidosis due to higher proportion of women with underlying rheumatoid arthritis. There is also a higher prevalence of AA amyloidosis in developing countries because of higher prevalence of infectious diseases [33,35].

In the head and neck, amyloidosis occurs in 19% of cases [38] and can affect skin [5,6], oral cavity [7,8], nasal cavity [9,10,39], pharinx [11,40], parotid gland [2], ear [12,13] and larynx [3,4]. In the skin, it can be localized or a symptom of systemic form. Localized form is rare and there are dermatological subdivisions into three types. The nodular type (red-brownish nodules) affects generally face and ears and is related to AL amyloidosis [5,6,41]. In oral cavity, often the manifestation is part of the primary systemic form [15] with macroglossia and various degrees of functional impairment. Involvement of other oral cavity sites are sporadic [7,42] but may manifest itself in a spectrum ranging from lesions that mimic malign neoplasms [43], purpura [44] and even haemorrhagic diathesis [45].

In the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, there are about 15 reports of localized primary amyloidosis [46], all diagnosed and treated after exuberant clinical manifestations such as epistaxis, hearing loss and pain [9,10,15,47] and, as in the oral cavity, mimicking malignancy. In the pharynx, a recent study [48] showed that the involvement of this organ represents 6% of localized primary AL amyloidosis cases. There are 14 pharyngeal involvement reports in literature [11], most related to the Waldeyer´s ring and only three related to hypopharynx [11,15]. Regarding Parotid only two cases were found in literature review [2,49]. Moreover, ear amyloidosis case reports [12,13,50] emphasize that ear involvement relates to localized form, it´s usually associated with lower morbidity and, most of times, there is possibility of clinical treatment.

Larynx is the most affected organ in head and neck localized amyloidosis [3,4,11,15,18,51,52]. Initially described in nineteenth century [53], there are a large number of laryngeal amyloidosis case reports and case series in literature. Unlike involvement in the oral cavity, laryngeal involvement is rarely associated with systemic form and familial AApoAI amyloidosis and is often related to localize AL amyloidosis [53-55]. The main symptom is hoarseness [15,51,53,56], there may be cough, hemoptysis and foreign body sensation [57], depending on lesions location and distribution pattern (if they are diffuse or a single tumor) [58]. The most commonly affected site within the larynx are the false vocal folds [3,4,15,52,56,57,59] and there is a report of patients with concurrent tracheal involvement [60]. There is no relationship with smoking, drinking, vocal abuse or recurrent infections, and etiology may be related to several unusual changes in aminoacid chains that generates local plasma cells dysfunction and the production of structurally abnormal immunoglobulins that become amyloidogenic substract [59,54]. The treatment of choice is endoscopic resection [15,54,57,58], requiring follow-up due to high rates of local recurrence. There are reports of other treatments modalities or multimodal treatments [58,59], however none have shown better local control then the gold standard.

There is no description in the literature of multiple sites in the head and neck as in the present case. The patient had lesions in cervical and face skin, ear, both parotid glands, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx and trachea, with positive histopathologically for all this sites. After proper screening has been excluded systemic disease and any underlying infection, prevailing diagnosis of localized primary AL amyloidosis involving multiple sites in the head and neck.

The specificity and sensitivity of histopathological diagnosis depends on the pathologist’s experience, quality of material used for preparation and the amount of material available for analysis [61], so false-positives or false-negatives are common. Using Congo red staining and electron microscopy can increase method´s sensitivity [61,62]. According to the latest amyloidosis diagnosis guideline, it is diagnosed by specimen histopathological examination, wich has to be Congo red positive and present an apple-green birefringence under polarized light [63]. In this case, diagnosis was given by an experienced pathologist in the area and carefully respecting these histopathological criteria. After histopathological diagnosis with Congo red, must be: (I) investigated existence of underlying neoplastic, infectious or inflammatory processes; (II) set the type of amyloid deposit; and (III) evaluated other organs involvement [61]. In the screening for underlying processes, in our case we find history of Rheumatoid Arthritis clinically controlled and presence of light chains AL Ig proteins. All amyloid disease need to have its amyloid type defined as this will be important to define treatment [64], so we chose to research prescursors proteins of the two most common groups of amyloidosis as well as other previously discussed familiar forms [55]. Immunohistochemistry, although a rising auxilliary method for subtyping amyloidosis, was not necessary in this case.

The relation between amyloidosis and rheumatoid arthritis is already long-known [65-69]. However only AA amyloidosis is described as a severe complication of this disease, there is no description associating it with localized AL amyloidosis, only sporadic cases of articular symptoms that do not close diagnostic for rheumatoid arthritis following paraneoplastic AL amyloidosis [70]. In our case, there was a arthropathy history of about 10 years with good symptom control through acupuncture and use of Chinese medicine. It was not filled the classical rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses criteria during the patient follow-up, and there was no medical record of previous monitoring that could not prove this diagnosis, nor performed imaging (PETCT) demonstrated amyloid deposits in joints, leading to the judgement that the presented polyarthropathy may be secondary to amyloidosis and not otherwise. The onset of joint symptoms before amyloid deposits manifestations could be related to presence of monoclonal protein in serum years before the first amyloidosis symptoms [71].

The evaluation of other organs involvement has to be omnibus so that an appropriate treatment and prognosis estimate can be settled down. In this case the patient had no clinical or laboratory signs of renal dysfunction, 24-hours proteinuria and creatinin clearance were normal. Cardiac function was investigated according to 2005’s guideline suggested protocol [63], thus an electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram were performed, both normal for age group, showing no cardiac deposits, vegetation or dysfunction, excluding cardiac involvement. Liver and gastrointestinal involvement in this case can be excluded by the absence of signs and symptoms such as hepatomegaly, intestinal dysmotility, weight loss and normal alkaline phosphatase. Moreover PET-CT showed no hepatic or splenic deposits, common involvements that are clinically irrelevant at early stages [61]. Similarly, nervous system involvement (peripheral and autonomic) can be ruled out based on clinical history, so an electromyography and specialized neurological examinations were unnecessary.

Concerning the left pleural effusion a pleural biopsy could be performed. Because lung involvement can occur in two ways: Nodular (considered a localized form [72]) and interstitial diffuse (systemic disease manifestation [63]). A thoracoscopy with positive pleural biopsy for amyloidosis could set another rare site involvement in the same patient [73,74], but considering negative PET-CT and an innocent pleural fluid examination, the involvement of this site can be safely excluded without an invasive procedure. There was no possibility of multiple myeloma since the patient did not have any event defining myeloma [75,76] as bone lesions and renal failure, or 10% or more of neoplastic clone in myelogram. Urine dosage of Bence - Jones protein was also negative. Adding to it, possibility of familial form was cleared by clinical history and dosage of AI and AII Apolipoprotein related to hereditary amyloidosis [55]. Therefore, diagnosis of this case was defined as primary, since there was no chronic inflammatory condition, infectious disease, underlying neoplastic process, nor other organ involvement, except in head and neck region.

There was a long-term peripheral joint disease associated, but without fulfill criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Amyloid deposition derived from light chain immunoglobulins, so the final diagnosis was localized primary AL amyloidosis in head and neck with asocciated rheumatoid component, setting a case not reported before in the literature. Initial treatment used for head and neck amyloidosis is primary lesion surgical resection with variable recurrence rates according to affected subsite [16,50,54], so outpatient follow-up should be ad eternum. In the case presented, considering multiple affected sites and the diffuse lesions, complete resection was not feasible, restricting surgical treatment to tracheostomy, for management of obstructive dyspnoea, bilateral superficial parotidectomy and oropharynx, oral cavity and neck skin biopsies for diagnostic purposes. After setting diagnosis, the great disease volume demanded a decrement in pathological deposited light chains, thus systemic AL amyloidosis clinical treatment was elected for the case.

Pulse therapy was started with prednisone and colchicine treatment that was inferior to Melphalan + prednisone in clinical randomized trials [71,77]. As there was a partial response to initial treatment, introduction of Melphalan and a plasmapheresis was scheduled in order to intensify response and as attempt to fully recover involved organs; however there was treatment discontinuation, because patient decided to return to his country. As a rare condition in the spectrum of a disease that is also rare, it is impossible conclude something about its treatment. The proper treatment of primary AL amyloidosis is in constant updating with use of several new drugs [33,71,77]. The AL amyloidosis has excellent prognosis, especially if there is no associated clinical syndrome as congestive heart failure and multiple myeloma [48]. Neverthless, in this case, it is noted significant morbidity, even after medical treatment, partial regression of cutaneous lesions and impossibility of decannulation, as well as need for further treatment and greater risk of adverse effects such as febrile leukopenia and myelodysplasia. As there was treatment discontinuation this patient has a very poor prognosis when it comes to disease progression and survival.

Conclusion

Amyloidosis is a hetereogeneous group of diseases characterized by deposits of amyloid fibrils in various tissues causing functional and anatomical damage. It is classified according to deposit protein type, affected location and clinical manifestations. Among amyloidosis types, the most clinically importants are: AL amyloidosis, AA Amyloidosis, ATTR Amyloidosis and Aβ2M amyloidosis. Head and neck amyloidosis occurs in 19% of cases and may affect the skin, ear, nasal cavity, oral cavity, parotid, pharynx and larynx. Larynx is the most commonly affected organ in this region, accounting for the largest number of case reports and case series in the literature, with treatment and well-established management. The diagnosis is made based on histopathologycal examination and biochemical characterization of amyloid type. The treatment is based on the surgical resection with variable recurrence rates, according to affected organ, and clinical treatment is reserved for cases of systemic disease or advanced local disease control. Considering the case presented, there is no similar report in literature. We described a case of localized primary AL amyloidosis at multiple sites in head and neck, showing exuberant cervical/face skin, ear, oral cavity, pharynx and larynx histopathollogically proven involvement, and partial response to chemotherapy.

Declarations

Consent to participate: not applicable

Consent for publication: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Availability of data and material: not applicable.

Competing interests: the authors declare they have no competing interests.

Funding: There was no funding during article preparation.

Authors’ contributions

JGMP was responsible for reviewing the amyloidosis classification and wrote the article. JFO, ARLM, PJCS and JMAV were involved in the review of amyloidosis in head and neck. TPF was involved indrafting the case presentation. TCF was involved in histopathological details of diagnosis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Lang SM, Täuscher D, Füller J, Müller AH, Schiffl H (2015) Multifocal primary amyloidosis of the airways: Case report and review of the literature. Respir Med Case Rep 15: 115-117.

- Nandapalan V, Jones TM, Morar P, Clark AH, Jones AS (1998) Localized amyloidosis of the parotid gland: a case report and review of the localized amyloidosis of the head and neck. Head Neck 20(1): 73-78.

- Caporrino Neto J, Alves NS, Gondra Lde A (2015) Laryngeal amyloidosis presenting as false vocal fold bulging: clinical and therapeutic aspects. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 81(2): 219-221.

- Kennedy TL, Patel NM (2000) Surgical management of localized amyloidosis. Laryngoscope 110(6): 918-923.

- Schipper CR, Cornelissen AJM, Welters CFM, Hoogbergen MM (2015) Treatment of rare nodular amyloidosis on the nose: A case report. JPRAS Open 6: 25-30.

- Gérard E, Ly S, Cogrel O, Pham-Ledard A, Fauconneau A, et al. (2016) Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Ann Dermatol Venereol 143(2): 134-138.

- Pentenero M, Bonino LD, Tomasini C, Conrotto D, Gandolfo S (2006) Localized oral amyloidosis of the palate. Amyloid 13(1): 42-46.

- Angiero F, Seramondi R, Magistro S, Crippa R, Benedicenti S, et al. (2010) Amyloid deposition in the tongue: clinical and histopathological profile. Anticancer Res 30(7): 3009-3014.

- Nakayama T, Otori N, Komori M, Takayanagi H, Moriyama H (2012) Primary localized amyloidosis of the nose. Auris Nasus Larynx 39(1): 107-109.

- Kumar B, Pant B, Kumar V, Negi M (2016) Sinonasal Globular Amyloidosis Simulating Malignancy: A Rare Presentation. Head Neck Pathol 10(3): 379-383.

- Hammami B, Mnejja M, Kallel S, Bouguecha L, Chakroun A, et al. (2010) Hypopharyngeal amyloidosis: A case report. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 127(2): 83-85.

- Domingos C R, Sousa RF, Becker HMG, Crosara PFTB, Guimarães RES (2013) Ear injury as the only manifestation of amyloidosis. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology 79(1): 119.

- Wasano K, Saito H, Kanzaki S, Ogawa K (2014) Keratinic amyloidosis of the external auditory canal. Auris Nasus Larynx 41(1): 97-100.

- Pietruszewska W, Wągrowska-Danilewicz M, Klatka J (2014) Amyloidosis of the head and neck: a clinicopathological study of cases with long-term follow-up. Archives of medical science: AMS 10(4): 846-852.

- Jacques TA, Giddings CEB, Hawkins PN, Stearns MP (2013) Head and neck manifestations of amyloidosis. The Otorhinolaryngologist 6(1): 35-40.

- Kaltoft B, Schmidt G, Lauritzen AF, Gimsing P (2013) Primary localised cutaneous Amyloidosis-systematic review. Dan Med J 60(11): 1-4.

- Cengiz Mİ, Wang HL, Yıldız L (2010) Oral involvement in a case of AA amyloidosis: a case report. Journal of medical case reports 4(1): 200.

- Gouvêa AF, Ribeiro ACP, León JE, Carlos R, de Almeida OP, et al. (2012) Head and neck amyloidosis: clinicopathological features and immunohistochemical analysis of 14 cases. J Oral Pathol Med 41(2): 178-185.

- O’Reilly A, D’Souza A, Lust J, Price D (2013) Localized Tongue Amyloidosis A Single Institutional Case Series. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 149(2): 240-244.

- Maria Inês Silva, Hugo Rodrigues, Sara Tavares, Carla André, Maria Helena Rosa, et al. (2012) Duas formas de apresentação da amiloidose em ORL. Revista Portuguesa de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia Cérvico-Facial 50(2): 159-164.

- Kyle KA, Bayed KD (1975). Amyloidosis: review of 236 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 54(4): 271-299.

- Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Ikeda SI, Merlini G, et al. (2014) Nomenclature 2014: amyloid fibril proteins and clinical classification of the amyloidosis. Amyloid 21(4): 221-224.

- Takahashi N, Glockner J, Howe BM, Hartman RP, Kawashima A (2016) Taxonomy and Imaging Manifestations of Systemic Amyloidosis. Radiol Clin North Am 54(3): 597-612.

- Naiki H, Okoshi T, Ozawa D, Yamaguchi I, Hasegawa K (2016) Molecular pathogenesis of human amyloidosis: Lessons from β2‐microglobulinrelated amyloidosis. Pathol Int 66(4): 193-201.

- Westermark P (2005) Aspects on human amyloid forms and their fibril polypeptides. FEBS J 272(23): 5942-5949.

- Pepys-Vered ME, Pepys MB (2014) Targeted treatment for amyloidosis. The Israel Medical Association journal: IMAJ 16(5): 277.

- Aly PDDF, Braun HJ, Missmahl HP (1969) 12/Amyloid involvement and monoclonal immunoglobulins. In: Westphal O, Bock HE, Grundmann E, Current Problems in Immunology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, New York, USA, pp. 295-301.

- Isobe T, Osserman EF (1974) Patterns of amyloidosis and their association with plasma-cell dyscrasia, monoclonal immunoglobulins and Bence-Jones proteins. N Engl J Med 290(9): 473-477.

- Missmahl HP (1968) Reticulin and collagen as important factors for the localization of amyloid. The use of polarization microscopy as a tool in the detection of the composition of amyloid. Symposium on Amyloidosis, Excerpta Medica Foundation, Amsterdam.

- Husby G, Sletten K (1986) Chemical and clinical classification of amyloidosis 1985. Scand J Immunol 23(3): 253-265.

- Linke RP, Oos R, Wiegel NM, Nathrath WB (2006) Classification of amyloidosis: misdiagnosing by way of incomplete immunohistochemistry and how to prevent it. Acta Histochem 108(3): 197-208.

- Gopalswamy M, Kumar A, Adler J, Baumann M, Henze M, et al. (2015) Structural characterization of amyloid fibrils from the human parathyroid hormone. Biochimica Biophys Acta 1854(4): 249-257.

- Hazenberg BP (2013) Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 39(2): 323-345.

- Babburi S, B R, Rv S, V A, Srivastava G (2013) Amyloidosis of the tongue-report of a rare case. J Clin Diagn Res (12): 3094-3095.

- Hemminki K, Li X, Försti A, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2012) Incidence and survival in non-hereditary amyloidosis in Sweden. BMC Public Health 12(1): 974.

- Kyle RA, Linos A, Beard CM, Linke RP, Gertz MA, et al. (1992) Incidence and natural history of primary systemic amyloidosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950 through 1989. Blood 79(7): 1817-1822.

- Pinney JH, Smith CJ, Taube JB, Lachmann HJ, Venner CP, et al. (2013) Systemic amyloidosis in England: an epidemiological study. Br J Haematol 161(4): 525-532.

- Penner CR, Müller S (2006) Head and neck amyloidosis: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Oral oncol 42(4): 421-429.

- Panda NK, Saravanan K, Purushotaman GP, Gurunathan RK, Mahesha V (2007) Localized amyloidosis masquerading as nasopharyngeal tumor: a review. Am J Otolaryngol 28(3): 208-211.

- Olivier Ghekiere, Gauthier Desuter, Birgit Weynand, Emmanuel Coche (2003) Hypopharyngeal amyloidoma. American journal of roentgenology 181(6): 1720-1721.

- Moon AO, Calamia KT, Walsh JS (2003) Nodular amyloidosis: review and long-term follow-up of 16 cases. Arch Dermatol 139(9): 1157- 1159.

- Larissa Araújo Queiroz, Lívia Souza Pugliese, Luciana Carvalho, Thiago Marcelino Sodré, Samilly Silva Miranda, et al. (2014) Amyloidosis: Expression in Oral Cavity. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology 117(2): e198.

- Silva WP, Wastner BF, Bohn JC, Jung JE, Schussel JL, et al. (2015) Unusual presentation of oral amyloidosis. Contemp Clin Dent 6(1): 282-284.

- McCormick RS, Sloan P, Farr D, Carrozzo M (2015) Oral purpura as the first manifestation of primary systemic amyloidosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54(6): 697-699.

- Marconcini LAL, Stewart FM, Sonntag L, Stevens E, Burwick N (2015) AL Amyloidosis Complicated by Persistent Oral Bleeding. Case reports in hematology 2015.

- Naidoo YS, Gupta R, Sacks R (2012) A retrospective case review of isolated sinonasal amyloidosis. J Laryngol Otol 126(6): 633-637.

- Forde R, Ashman H, Shah D, Williams EW (2014) Primary Amyloidosis of the Nose Presenting with Refractory Epistaxis and Systemic Involvement-A Rare Phenomenon. West Indian Med J 63(4): 382-383.

- Kourelis T, Buadi F, Gertz MA, Kumar S, Lacy MQ, et al. (2015) Presentation and Outcomes of Localized Amyloidosis: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Blood 126(23): 4197-4197.

- Vavrina J, Müller W, Gebbers JO (1995) Recurrent amyloid tumor of the parotid gland. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 252(1): 53-56.

- Wenson SF, Jessup CJ, Johnson MM, Cohen LM, Mahmoodi M (2012) Primary cutaneous amyloidosis of the external ear: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 17 cases. J Cutan Pathol 39(2): 263-269.

- Saha KL, Datta PG, Dutta UK, Rahman AK, Akhter S (2015) Primary Amyloidosis of Larynx-A Case Report. Bangladesh J Otorhinolaryngol 20(2): 98-101.

- Fries S, Pasche P, Brunel C, Schweizer V (2015) Laryngeal amyloidosis: a clinical case and review of literature. Revue medicale suisse 11(488): 1796, 1798-1802.

- Borow A (1873) Amyloide degenaeration von larynxtumoren. Canule seiber jahre lang Getrager. Arch Klin Chir 15: 242-246.

- Hazenberg AJ, Hazenberg BP, Dikkers FG (2016) Long-term followup after surgery in localized laryngeal amyloidosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273(9): 2613-2620.

- Hazenberg AJ, Dikkers FG, Hawkins PN, Bijzet J, Rowczenio D, et al. (2009) Laryngeal presentation of systemic apolipoprotein A‐I-derived amyloidosis. Laryngoscope 119(3): 608-615.

- Bozkus F, Ulas T, Lynen I, Ozardali I, Sans I (2013) Primary localised laryngeal amyloidosis. J Pak Med Assoc 63(3): 385-386.

- Santosh K Swain, Mahesh C Sahu (2015) Isolated primary amyloidosis of the epiglottis presenting as a long-standing foreign body sensation in throat: A case report. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 10(4): 488-491.

- Neuner GA, Badros AA, Meyer TK, Nanaji NM, Regine WF (2012) Complete resolution of laryngeal amyloidosis with radiation treatment. Head Neck 34(5): 748-752.

- Ma L, Bandarchi B, Sasaki C, Levine S, Choi Y (2005) Primary localized laryngeal amyloidosis: report of 3 cases with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 129(2): 215-218.

- Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Kurtin PJ, Kyle RA (1992) Laryngeal amyloidosis: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 106(4): 372-377.

- Real de Asúa D, Costa R, Galván JM, Filigheddu MT, Trujillo D, et al. (2014) Systemic AA amyloidosis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Clin Epidemiol 6: 369-377.

- Clement CG, Truong LD (2014) An evaluation of Congo red fluorescence for the diagnosis of amyloidosis. Hum Pathol 45(8): 1766-1772.

- Gertz MA, Comenzo R, Falk RH, Fermand JP, Hazenberg BP, et al. (2005) Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis. Am J Hematol 79(4): 319-328.

- Linke RP (2012) On typing amyloidosis using immunohistochemistry. Detailled illustrations, review and a note on mass spectrometry. Prog Histochem Cytochem 47(2): 61-132.

- Missen GAK, Taylor JD (1956) Amyloidosis in rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Pathology 71(1): 179-192.

- Cohen AS (1968) Amyloidosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. The Medical clinics of North America 52(3): 643-653.

- Husby G (1975) Amyloidosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of clinical research 7(3): 154-167.

- Husby G (1984) Amyloidosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 3(2): 173-180.

- Elkayam O, Hawkins PN, Lachmann H, Yaron M, Caspi D (2002) Rapid and complete resolution of proteinuria due to renal amyloidosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum 46(10): 2571-2573.

- Kristel B Van Landuyt, Mirian J Starmans, Ralph M Peeters, Kon-Siong G Jie (2012) Atypical polyarthritis as a major manifestation of light chain disease. Annals of Hematology 91(10): 1653-1655.

- Muchtar E, Buadi FK, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA (2016) Immunoglobulin Light-Chain Amyloidosis: From Basics to New Developments in Diagnosis, Prognosis and Therapy. Acta Haematol 135(3): 172-190.

- Utz JP, Swensen SJ, Gertz MA (1996) Pulmonary amyloidosis. The Mayo Clinic experience from 1980 to 1993. Ann Intern Med 124(4): 407-413.

- Yoshiya S, Maruyama R, Koga T, Shikada Y, Yano T, et al. (2012) Localized pleural amyloidosis: report of a case. Surg Today 42(6): 597-600.

- Kavuru MS, Adamo JP, Ahmad M, Mehta AC, Gephardt GN (1990) Amyloidosis and pleural disease. Chest 98(1): 20-23.

- Rajkumar SV (2016) Myeloma today: Disease definitions and treatment advances. Am J Hematol 91(1): 90-100.

- Vincent Rajkumar, Robert A Kyle (2005) Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 80(10): 1371-1382.

- Gertz MA (2013) Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: 2013 update on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol 88(5): 416-425.