- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

From “Story for” to “Reference to”: Genetic Genealogy and Origin Setting

Lolita Nikolova*

Open Global Research Academy, USA

Submission: August 31, 2018; Published: October 01, 2018

*Corresponding author: Lolita Nikolova, Open Global Research Academy, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, Email: inikol@iianthropoligy.org

How to cite this article: Lolita Nikolova. From “Story for” to “Reference to”: Genetic Genealogy and Origin Setting. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 6(5): 555700. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.06.555700

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

Abstract

Genetic genealogy is a complex discipline that employs a variety of evidence to create a truthful model about the ancestry of individuals and lineages by discovering close or distant genetic matches (CGM and DGM) (“cousins”) and producing models of ancient origin (“ethnicity”) based on individual data. The role of genetic data varies, as does the way it has been used at different levels of research. Close and distant genetic matches (CGM & DGM) have been discovered based on comparing the quantity and character of matching centiMorgans. While close relatives recognized as such by the high percentage of shared centiMorgans can be cousins / uncles / aunts, distant genetic matches described as 4th-8th“cousins” are defined based on small quantity of centiMorgans matches, a scenario which may have different explanations.

To determine ancient origin (“ethnicity”), a researcher must compare thousands of data to locate the origins of the tested individuals in numerous regions throughout the world. The methodology is still not well developed and explained, so this work analyzes genetic origin as a scientific problem instead. The foundation of the genetic origin search incorporates results from individual DNA testing, most popular of which are ancestry.com [1], 23 & Me [2], Family Tree DNA & Helix [3,4]. The theoretical background is analyzed in scientific literature [5-10] or on numerous social media websites [10].

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

The collected DNA data made it possible to outline the genetic contribution to genetic genealogy in 3 ways:

a. Comparing the results from different companies (Ancestry.com, 23 & Me, Family Tree DNA, and Helix) for the same person

b. Comparing different individuals’ results from the same company (9 participants).

c. Comparing the results of the tested participants with the available data from the different genealogical companies or online specialized websites

Since genetic genealogy depends on the analyses carried out by DNA labs, one very important task was to scale the trust in the various interpretations. Two of the DNA aspects in genealogy-ancient origin/ethnicity and the “genetic cousins” terminology-can be defined as highly speculative or too broad-spectrum. Instead of the term “genetic cousin,” this work uses the term “genetic matches” (GM). The scale of trust increases with the measuring of the centiMorgans for the genetic matches and in defining the haplogroups.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

Results from Tests Conducted on the Same Participant through Different Companies

Participant UE011959 submitted samples and received results from four companies: Ancestry.com, 23&Me, FamilyTreeDNA, and Helix. The information obtained from these tests provided a comprehensive database that allowed for a variety of comparative analyses. The contributions of autosomal and mitochondrial research to genetic genealogy were particularly noteworthy. Two main conclusions are the subject of the current project: “genetic cousins” and “ethnical origin.” In the section on “genetic cousins,” I included only:

a. Cases of relations based on a very high cM match,

b. Those cases clarified and confirmed through interviews, or

c. Those cases in which information was previously known to the participants in the genetic tests.

Participant UE011959: “Genetic Cousins”

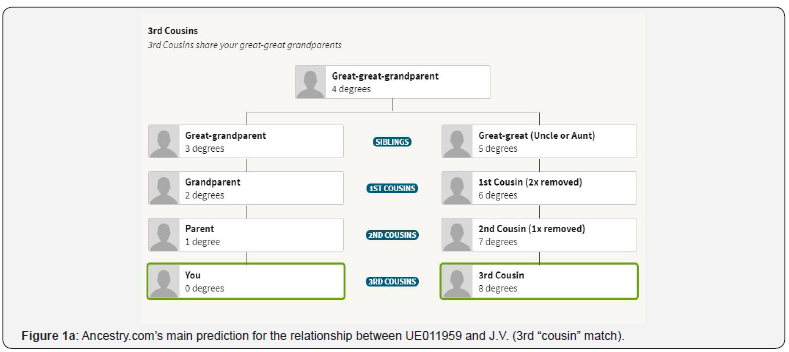

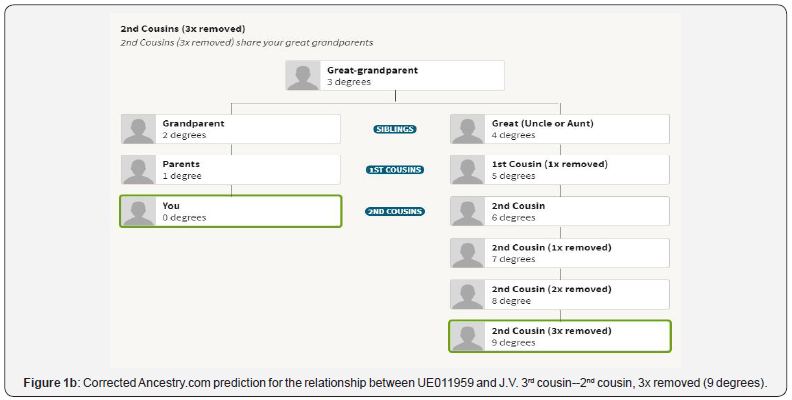

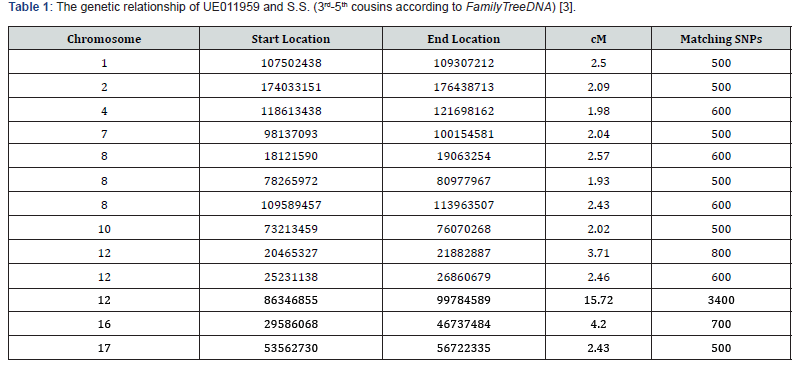

The Ancestry.com (2018a) matches for UE011959 revealed a “3rd genetic cousin,” although further explanation clarifies that the relationship could be 2nd cousin 1x removed or perhaps 4th cousin (Figure 1a). The prediction falls in the 2% of cases that are not precise, since Ancestry.com insists that its tests correctly recognize genealogical relationships in 98% of cases. An interview with the moderator of J.G.’s tree clarified that UE011959 found the uncle of her father, so the relation between her and J.G. was of the 9th degree-second cousin, 3x removed (Figure 1b). The second case of a genealogical cousin of UE011959 was revealed by FamilyTreeDNA. S.S. was recognized as “3rd-5th cousin” based on 46 cM match in 12 sectors (Table 1). Genealogically, S.S. is a 2nd cousin of UE011959. The imprecise conclusion of FamilyTreeDNA is due to the small quantity of shared cM (only 46 cM).

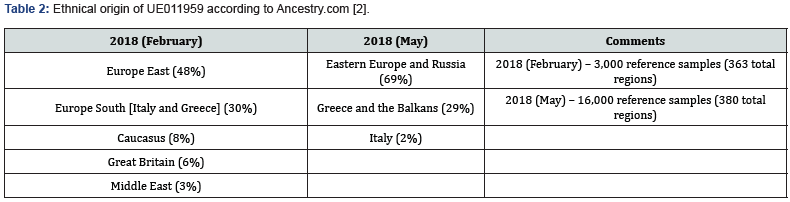

Participant UE011959: Ethnical Origin

Ancestry.com changed its conclusion regarding the ethnical origin of UE011959 within several months (Table 2). According to Table 2, the percentage of the subject’s origin from Eastern Europe (now described as Eastern Europe and Russia) has increased (69%), Greece was combined with the Balkans (29%), and the three regions originally described as the Caucasus (8%), Great Britain (6%), and Middle East (3%) were completely disregarded. Such transformation of the results contrasts with the results of other companies and increases the gap between genetic genealogy and the genetic “method” of ethnic modeling since it becomes rather vague in terms of ethnical perspective regions like Russia. In this case, genetic genealogy does not overlap even with population genetics, since the map does not include results from the population genetics studies.

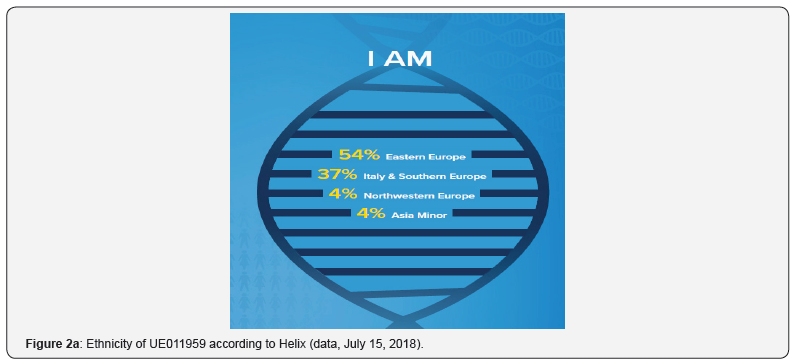

Helix’s conclusion (Figure 2a) is closer to Ancestry.com’s conclusions from February 2018. It is unclear whether the companies just used the same algorithm and Ancestry.com changed its algorithm later. The Helix model of ethnicity (Figure 2a) is based on a total of 932,870 participants in the project. It is interesting that, although Ancestry.com insists that they have millions of tested individuals, the interpretation of UE011959 is based on an extremely small sample of data. Since “Russia” is multi-ethnical, the new model of Ancestry.com (Table 2) has become even more ambiguous from the perspective of genetic genealogy. Genealogy, in principle, is a very specific science and the goal of genetic genealogy is to connect the individual with lineages or specific origin groups, not to create vague macroregional models, only some of which may have some meaning in population genetics. However, there is a big difference between the subject of genetic genealogy and population genetics.

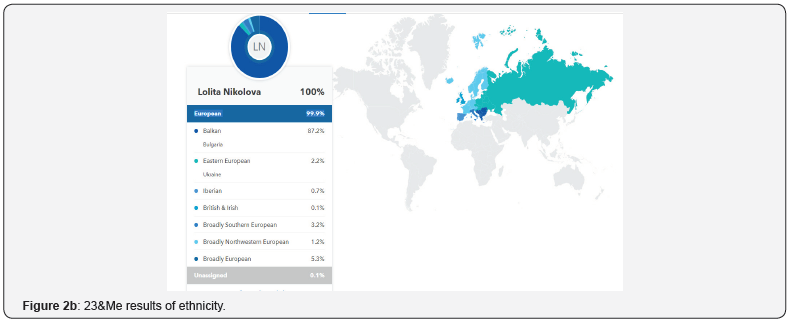

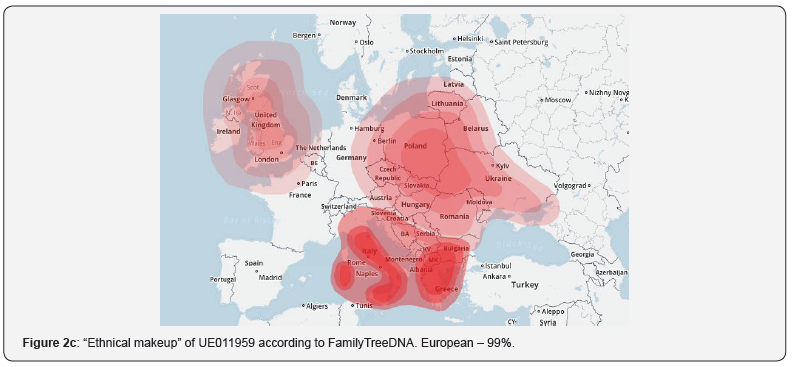

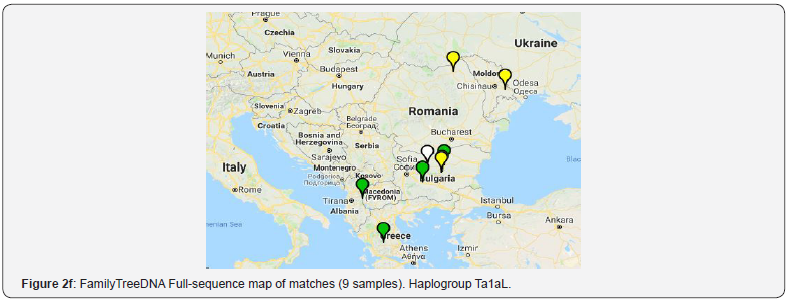

The results from the 23&Me test, which includes even mthaplogroup (Ta1a), may represent a more recent ethnical picture since the ethnical origin is defined as 87.2% Balkan (Bulgaria). In the case of 23 & Me, the biggest problem is also the fact that “Eastern Europe” includes not only Eastern Europe, but almost all of Asia (Figure 2b). The details from the mtDNA test of UE011959 at FamilyTreeDNA (Table 3) create a multilevel cultural genetic map of “ethnical makeup” referring to the Ta1aL haplogroup. The ethnical makeup map of FamilyTreeDNA (Figure 2c) differs from those of Ancestry.com and 23&Me. FamilyTreeDNA created the map based on full-sequence mitochondrial analysis, revealed as the T1a1L haplogroup.

The ethnical makeup can be better understood through the maps of HVR 1 (299 samples), HVR 2, and full-sequence matches (Figures 2d-2f) (Table 2). The narrative data about UE011959’s maternal origin correlates with the FamilyTreeDNA evidence (Figure 2f), since the grandmother of UE011959 was from Macedonia who migrated with the family (including 5 sisters) to Bulgaria. HVR 1 and HVR 2 obviously represent two consecutive chronological layers. HVR 1 may explain the so-called British origin with very ancient (possibly even rooted in Neolithic) intensive European population consolidation including the wider distribution of haplogroup T (Figure 2d). Very interesting is the similarity between HVR II (Figure 2e) and Full-sequence map of matches (Figure 2f), showing a dynamic of reshaping of the ethnical identity of the Balkans and East Europe over vast territories through marriages or a migration(s) of small groups of population. Having in mind that Figure 2d represents much deeper and longer chronological period, it can be concluded that the numerous genetic matches not necessarily refer to mass migrations in Antiquity as the more recent (and with short chronological span) models show (Figures 2e-2f). Accordingly, the mitochondrial DNA samples of living population need to be used very carefully for reconstruction of the population genetics history.

Participant UE011959: Genetic and Genealogical Data Matches

Genealogical data were gathered to integrate with the genetic data.

Croatian Collateral Data for UE011959: Croatian genealogical analogies go back to Corčula in several pedigrees with which UE011959 shares about 17-20 cM (across one or two DNA segments). One of the matches of UE011959, coded as RC012018, shared 20.7 cM across one DNA segment inferred by Ancestry.com as the 4th “cousin” relationship (good confidence). The attached pedigree showed that one of the maternal lines goes back to Croatia in Corčula.

Another match with roots in Corčula (CR022018) shares 19.8 cM across one DNA segment, interpreted by Ancestry.com as a possible 5th-8th “cousin” with good confidence. The third match with Corčula belongs to RC032018 (17.8 cM shared across two DNA segments). Further genealogical research of origin of Corčula collateral lineages may help to cross better the data possibly with the maternal ancestry of UE011959 despite of the small percent of genetic match. Such future genealogical research may articulate better the meaning of the < 20cM – whether it has a genealogical root, or just refers to possible common ethnical origin.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

Another group of matches is due to the Bulgarian origin. UE022018 shares 19.5 cM across one DNA segment, which is inferred as a 5th-8th “cousin” with good confidence (Ancestry. com). The genealogical pedigree points to the existing Bulgarian origin of one of the lines of UE011959, the roots of which were in Kereka, Veliko Tirnovo, in northern Bulgaria. It is interesting to note the matches between UE011959 and IT012018. Both samples have 17.9 cM shared across one DNA segment (Ancestry. com). The roots of IT012018 are completely in Italy, according to the public pedigree. According to the public tree data, IT012018 (5th generation) was from Porcigatone, Parma, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, and was born on 1 February 1861. Her father, G. dit Z. F., was born on 18 March 1820 in Porcigatone (6th generation). Further research may provide evidence to learn about the genealogical context of the “5th-8th cousin” relationship from an Italian perspective.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

The results of Ancestry.com DNA test of UE011959 were analyzed above in the context of comparative analysis with the results from other companies (FamilyTreeDNA, 23&Me, and Helix). Eight more participants submitted samples to Ancestry.com for autosomal DNA results of their genetic ancestry..

Participant MJ101234: Genetic “Cousins” and “Ethnical Origin”

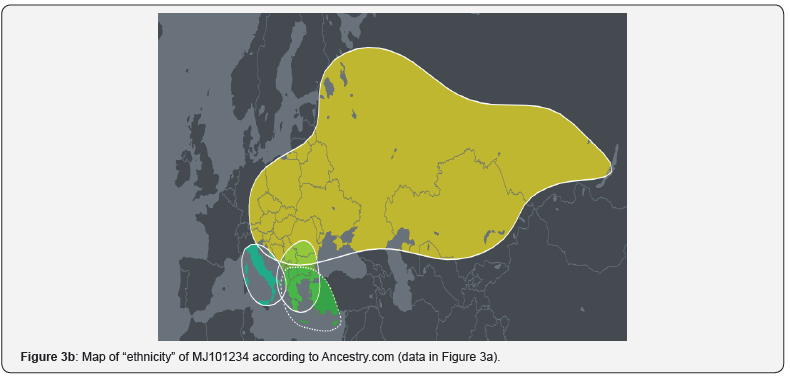

The traditional genealogical origin of MJ101234 is Bulgarian, tracing back to the early 19th century based on genealogical records. No 1st-3rd genetic “cousins” were documented among the matches of MJ101234. However, the proposed 4th “cousin” shares 42 cM, which can be a characteristic even of a 3rd cousin or a 2nd “cousin” 1 to 3 times removed. The origin of the match is Bulgaria, which supports the genetic data. Another distant genetic match with shared 18.8 cM (across one DNA segment) and with pedigree includes family names with origins in Yugoslavia, which points to Balkan origin. Two other distant “cousins” (sharing 16.1 cM across one DNA segment and 13.9 cM across one DNA segment, respectively) have origins in Romania. One more match with pedigree (sharing 15.6 cM across one DNA segment) has genealogical roots in Ioannina, Ipeiros, Greece. All these genealogical data in combination with the genetic matches favor the hypothesis about Paleo-Balkan genetic identity, which was multiethnic. In other words, the systematic analysis of the data allows us to develop the very terminology of genetic genealogy toward more correct and precise terms. In this case, the author proposes using the term “genetic identity / origin” instead of “ethnicity” and “genetic matches” instead of “cousin.” Ancestry.com provided the following framework of the “ethnicity” of MJ101234 (Figures 3a & 3b):

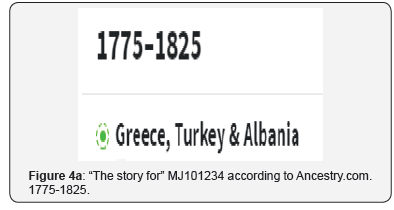

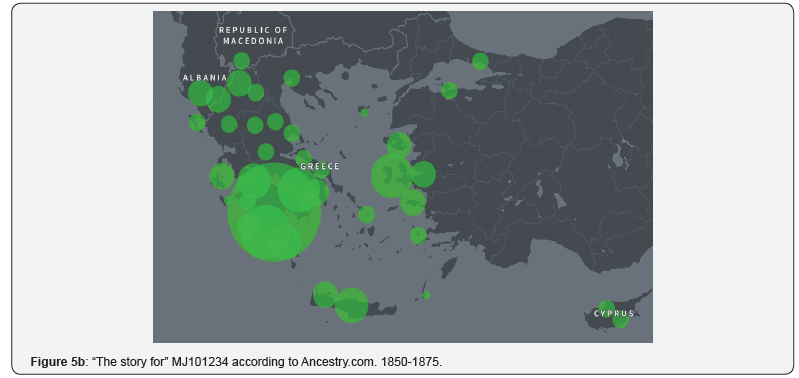

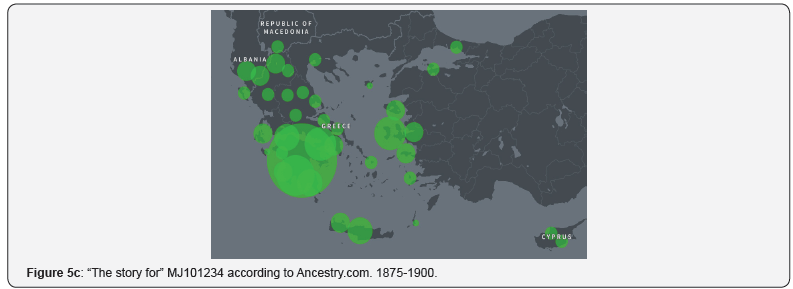

The map demonstrates a very vague method of determining the “ethnicity” of MJ101234, placing 64% of the origin before 1700 (according to its chronological frame) and almost all of it in Central or Eastern Eurasia. Since no haplogroup is provided (in contrast to 23&Me for the same price), it is unclear why western Europe is ignored and to which chronological span(s) before 1700 the map belonged. The region described as Eastern Europe and Russia primarily includes: Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Austria, Russia, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia. That means multi-ethnical countries, which also brings the use of the term “ethnicity” into question. The maps for 1775-1900 include several locations in Greece, Albania, and Turkey. Missing, however, is an explanation of how these shared autosomal compositions related specifically to MJ101234 (Figures 4-5c).

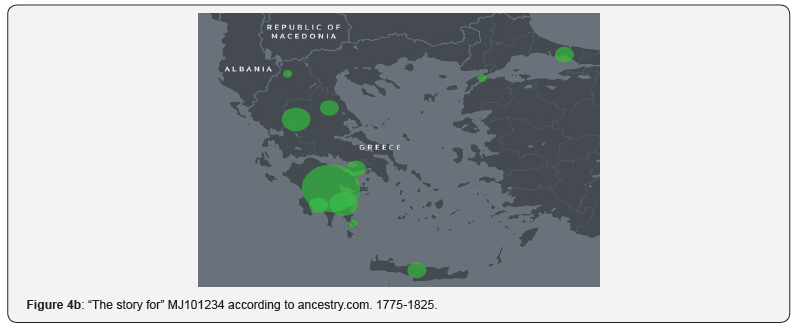

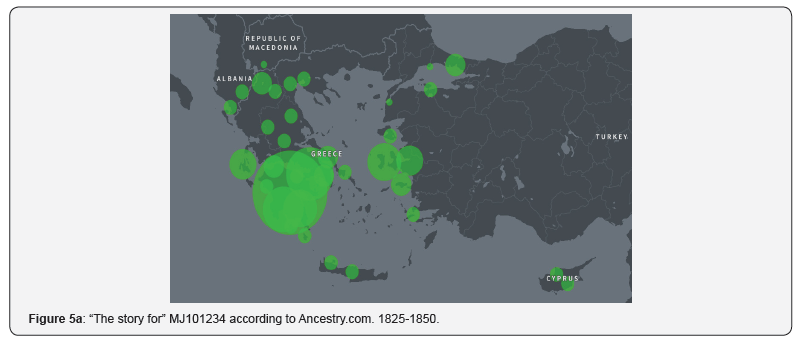

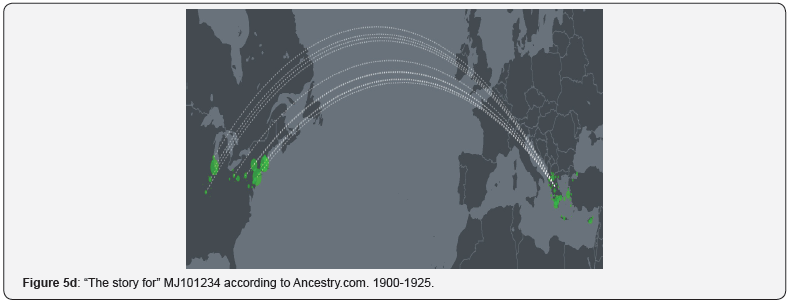

The open-ended interview with the participant revealed that there are no legends in the family about Greek, Turkish, or Albanian origin in the later 18th or early 19th century. This fact may indicate glitches in the Ancestry.com databank and in its methodology of interpreting the data from the Balkans. As more information is added to the databank, the map of the genetic data used may expand into Bulgaria, as well. Ancestry.com also offers five more chronological spans: 1825-1850, 1850-1875, 1875-1900, 1900-1925, and 1925-1950 (Figures 5d & 5e). The traditional genealogical data originate from the later 19th century, and all of them come from Bulgaria. That means none of the maps in Figure 5 relates to the personal origin of MJ101234, although they are presented as “DNA story for.” This is an extremely serious glitch in the way the genetic data are currently presented to the clients of commercial companies by attempting to attract buyers of DNA kits for genealogical purposes with interpretations that are not based on grounded theory.

Figures 5a-5e. “The story for” MJ101234 according to Ancestry. com. None of the maps present data that match the traditional genealogy. It is an example of a made-up ethnical model based on the limited database of Ancestry.com, which does not cover all regions even of tested individuals. These maps were rejected as an attribution of the ethnical identity of MJ101234 during the research. Figures 5d-5e not only show made-up ethnical models without any real connection to the tested individuals but also made-up migration, since the direct ancestors of MJ101234 did not migrate to the U.S. If there were migrations even of distant genetic relatives, they would migrate from Bulgaria. This is a good example of the limitation of applying models of population genetics to personal genetic history.

Ancestry.com states that its conclusion applies the science and the changes in their ethnical makeups reflect the development of science [2]. It seems, however, that the commercial goal of attracting customers dominates and conflicts with grounded theory in science. One very important fact is the absence of any pedigree for MJ101234 at Ancestry.com, which therefore does not allow the company to use traditional genealogical data for interpreting genetic data from previous centuries. In other words, while Ancestry.com has become the largest and the most unique world digital archive for family history, the communication of the DNA test results in the “Story for” section is in many cases misleading and damages the trust in the DNA data as a scientific mean for determining the dynamics of the individual cultural identity.

Participant TY012345: Genetic “Cousins” and “Ethnical Origin”

The Ancestry.com results came from February 2018 and were based on 3,000 samples. That means this sample was not updated in May 2018. Therefore, it is impossible in this research to compare samples even from the same company based on the same criteria. No close genetic “cousins” of TY012345 exist in the Ancestry.com database. However, the participant shares 94 cM across seven DNA segments with a person whose genealogical roots were in Bulgaria. The interview question did not produce additional information because the participant did not know many of the ancestors due to migration of the ancestral lineage in different parts of the world. A match with a person who had genealogical roots in Bulgaria is based on 28.9 shared cM across three DNA segments. A shared 22.4 cM across two DNA segments with a person who has multiethnic ancestral origins may help connect participant TY012345 with the branch of the ancestral tree that has origins in Plovdiv, Bulgaria. A match with 13.8 shared cM across two DNA segments has genealogical roots in the Czech Republic, which expands the genetic map to regions northwest of Bulgaria. The participant TY012345 shared 13.3 cM across two DNA segments with a person whose genealogical roots were in Croatia. The 11.6 shared cM across one DNA segment with a person whose family tree features Polish genealogical roots may show that the low quantity of shared cM point to very deep genetic roots of a vast population from Eastern Europe and the western Balkans. This conclusion increases the weight of the ethnical modeling by Ancestry.com if it was based in a strong methodology.

The “ethnicity” of TY012345 in Figures 6a & 6b represents four contributive regions: Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, and the Caucasus. Eastern Europe (40% of TY012345’s total ethnicity) includes Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Austria, Russia, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Lithuania, Latvia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia. This means that, if the data was updated, the Eastern Europe portion of the map would be like Figure 3b. Southern Europe (36% of TY012345’s total ethnicity) is Ancestry. com’s old division, which included Italy and Greece. The Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) is represented with 9% and the Caucasus with 8% (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey). Most curiously, the dominant Bulgarian roots have not been included either in Eastern Europe or in Southern Europe, although the map covers Bulgaria in both main contributive regions.

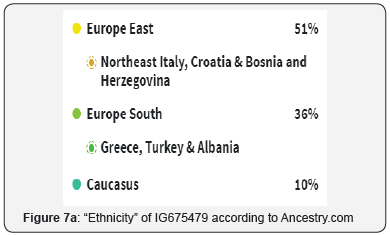

Participant IG675479: Genetic “Cousins” and “Ethnical Origin”

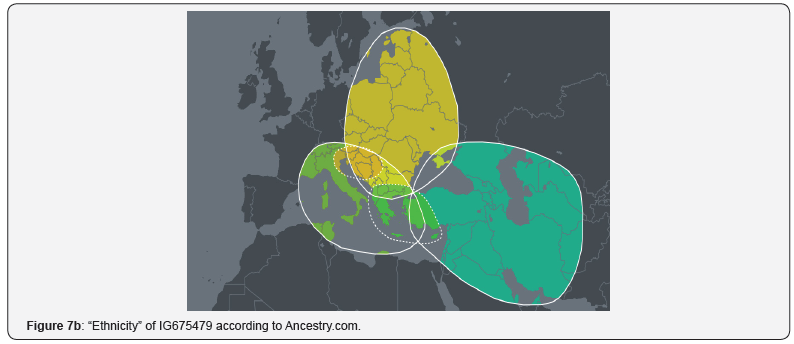

Participant IG675479 shares 93 cM across 6 DNA segments with a person who has roots in Burlozhnitsa, Sofia, Bulgaria, and is recognized as a 3rd-4th genetic “cousin” by Ancestry.com (Ancestry. com, 2018). Although the names were unknown, Burlozhnitsa is a common ancestral place that connects IG675479 with the genetic match. All her known genealogical ancestors were born in Bulgaria (19th-20th centuries). There are genealogically documented distant (5th-8th) genetic cousins that connect IG675479 with Italy (17.5 shared cM across one DNA segment), Macedonia (27.3 shared cM across two DNA segments), Romania (16.2 shared cM across one DNA segment), and so on. According to Ancestry. com “ethnicity,” IG675479’s genetic composition consists of three main components: East Europe (51%), South Europe (36%) and the Caucasus (10%). The interview with IG675479 documented the participant’s authentic excitement as she shared that her father had a light complexion and blue eyes, while her mother had darker coloring with dark eyebrows.

The map in Figures 7a & 7b shows the intersection of several genetic regions. The Bulgarian roots of IG675479 contradict the other maps offered for the period 1700-1900 as maps that document the personal genetic identity of the participant. However, genetic data from the northwestern and southern Balkans can relate to the possible dual ethnical origin of the paternal and maternal sides of IG675479.

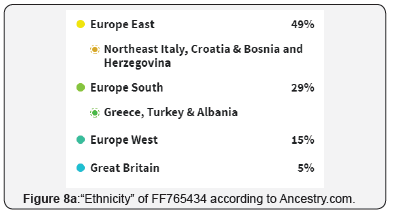

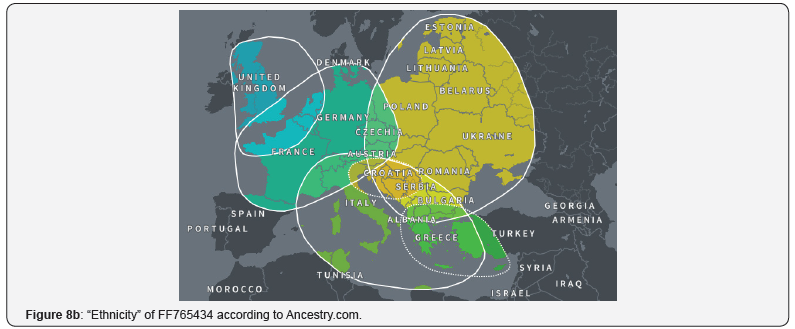

Participant FF765434: Genetic “Cousins” and “Ethnical Origin”

According to the interview, the participant’s paternal side has genealogical roots in Tetovo, Macedonia, while the maternal side has roots in Slovenia. He has four genetic “cousins” (shared 91-131 cM), but unfortunately, they do not have established pedigrees. However, among the numerous 4th-6th genetic “cousins,” several pedigrees reveal roots in Macedonia-some in Tetovo, Macedonia, in particular-and 20-54 shared cM. The data allows us to conclude that the autosomal DNA test correctly makes the genetic connection of FF765434 with Macedonia-Tetovo, where the father of the participant was born. In other words, the paternal side’s genetic context is more strongly documented for the time being.

The “ethnicity” conclusion of Ancestry.com gives higher weight to the so-called Eastern Europe region (49%). Comparing the genetic and genealogical data, we can also generally conclude that Ancestry.com’s specific linking of the participant’s test to Northeast Italy, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina is correct since his maternal side was from Slovenia (Figures 8a-8c). The second distinguished region (29%) is Greece, Turkey, and Albania (which also includes Macedonia) and is also generally correct, although a similarity with Bulgaria would be much more appropriate if there were enough samples or if the samples were used more precisely. The absence of individual-oriented research of the ethnicity is especially well documented in the case of FF765434 because there are pedigrees of individuals tested by Ancestry.com who have roots in Tetovo, Macedonia, while Ancestry.com’s genetic map from 1850 refers to Bitola, which is a considerable distance south of Tetovo. Accordingly, the maps do not include all samples even in cases in which there is an opportunity for the intersection of genetic and genealogical data. The absence of individually oriented research of the ethnicity is also documented by the fact that the maps of FF765434 and IG675479 are identical in terms of the core ethnical regions-northwest (named “Northeast Italy, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina”) and the southern Balkans (named “Albania, Greece, and Turkey”).

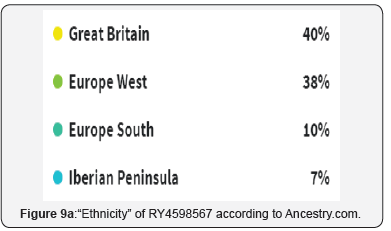

Participant RY4598567: Genetic “Cousins” and “Ethnical Origin”

The participant RY4598567 was surprised by the results from Ancestry.com because the test revealed three 1st cousins (the interview with the participants clarified they were his uncles and aunt). The quantity of shared centiMorgans is quite high for each of the three:

a. 1,834 cM shared across 55 DNA segments.

b. 1,684 cM shared across 58 DNA segments.

c. 1,614 cM shared across 63 DNA segments.

A large group of nine individuals includes 1st-2nd genetic cousins who share between 221 and 716 cM. Hundreds of distant cousins enrich the genetic history of RY4598567, with several public trees that show very deep roots in the U.S.

The “ethnicity” story for RY4598567 is composed of 4 contributive regions: Great Britain (40%), West Europe (38%), South Europe (10%) and the Iberian Peninsula (7%) (Figures 9a & 9b). England, Scotland, and Wales are the primary locations of the Great Britain ethnical component. It is interesting that, despite the high percentage of West Europe (38%), there is no location of core ethnical region provided. South European components refer primarily to Italy and Greece. The ethnical maps for the period from 1700 to 1925 are in fact not a story for RY4598567, but a general model of the early migration of English, Scots-Irish, and Germans who flocked to America and settled in the Ohio River Valley, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa as well as further inner migration in the U.S. (Figures 9c-9n). The maps are reproduced in this part of the research to illustrate that even in cases of intensive genetic and genealogical research (represented by the American genealogy) the defined “ethnicity” provided by Ancestry.com is a general model that has been delivered to clients with individual stories.

Figures 9m & 9n demonstrates the richness of the genetic database of American immigrants from the British Islands and Western Europe, which are only a model-reference to the genetic stories of the individual clients. Although labeled “Story for” they can be used as a template that requires genealogical verification of the data for the specific participant.

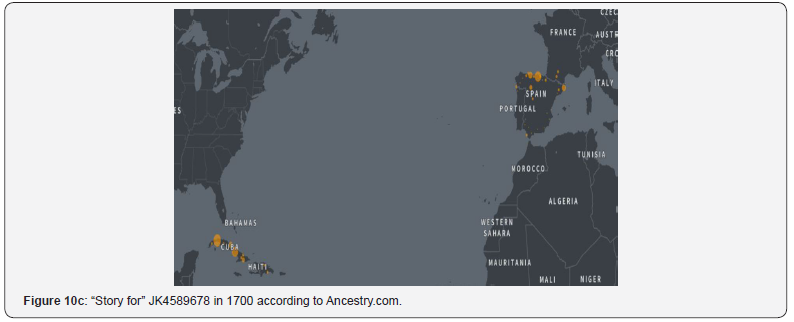

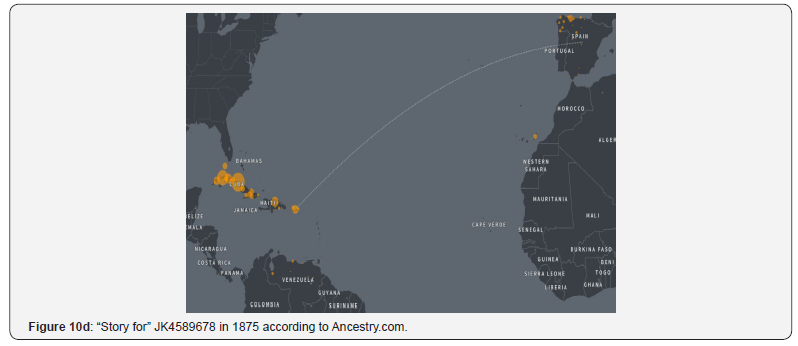

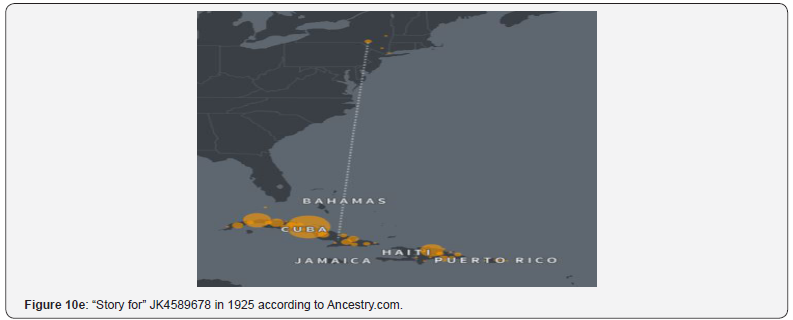

Participant JK4589678: Genetic “Cousins” and “Ethnical Origin”

The interview clarified that the participant had Cuban origin. The Ancestry.com results revealed a 1st-2nd genetic cousin with 563 shared cM across 34 DNA segments (R.P.), 2nd-3rd cousins with 242 shared cM across 15 DNA segments (D.P.), and 208 cM shared across 13 DNA segments (R.R.). One of them has a pedigree, which the participant was excited to learn about for the first time because of the broken contact with Cuba. Four individuals are in the group of 3rd-4th cousins with 94-121 shared cM. Among the numerous 4th-6th genetic “cousins” (sharing < 81cM) are several individuals with pedigrees that have roots in either Cuba or Spain.

The ethnicity of JK4589678 is complex: South Europe (37%), the Iberian Peninsula (26%), Ireland/Scotland/Wales (12%), Great Britain (10%), North Africa (5%) and Native American (5%) (Figure 10a). Primary matches located in South Europe come from Italy and Greece (26%-49%), while those in the Iberian Peninsula came from Spain and Portugal (10%-41%). The data from the British Islands partially overlap, while North Africa refers to the primary locations of Morocco, Western Sahara, Algeria, and Libya. The area of Native American origin is also broad-North America, Central America, and South America. However, as the previous critical analysis of the ethnicity of other participants shows, the cited locations are just a reference to possible ethnical origin because of the limited samples.

The following maps from Ancestry.com (1700-1950) briefly refer to the general picture of emigration to Cuba, Haiti, and northern Latin America from Spain and Portugal. Some of them are illustrated below (Figures 10b-10e). The genetic studies in the early 21st century is of extremely high quality and presenting such models of general migrations as a personal story satisfies as a general picture (in the way the participant JK4589678 felt seeing the map that even noted the birthplace of his father). These genetic studies show the limitations of specific branches of genetic researchers in their scholarly goals to apply the individual results by a most detailed reexamination of all data as they pertain to the individual results.

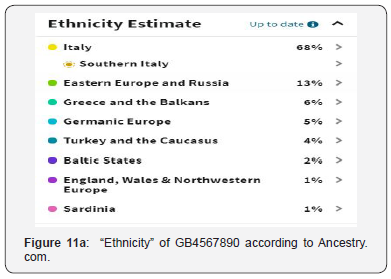

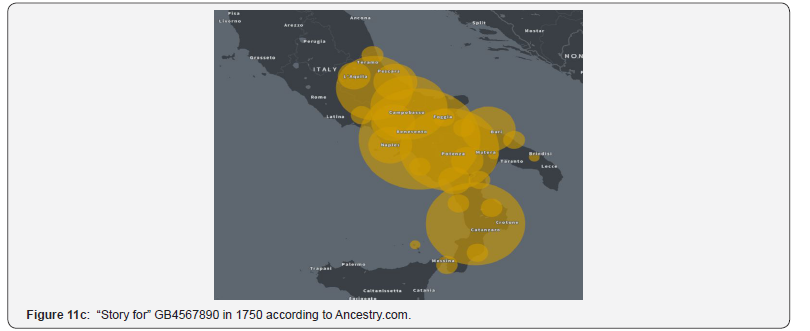

Participant GB4567890: Genetic “Cousins” and “Ethnical Origin”

The interview with the participant documented his dominant Italian origin. The Ancestry.com DNA results revealed two 1st-2nd cousins with shared 362 cM and shared 819 cM, respectively. Two 3rd-4th cousins share 93cM and 100cM. Among the numerous distant genetic “cousins” is one (J.C.) with a family list of the participants that also shows an origin in L’Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy.

The “ethnicity” map for GB4567890 is the presentation model of the Ancestry.com results updated in May 2018 that includes an extremely vast area of Russia, a Eurasian reference to the ethnical origin (Figures 11a & 11b). Generally, the DNA results overlap with the known information about the origin of GB4567890. The primary located area of Italy refers to Italy, San Marino, Vatican City, and Malta (64%-90%). The map in 1750 includes central and southern Italy (except Sicily) (Figure 11c). In comparison to 1750, the expansion of the map over Sicily in 1800 logically raises questions about whether this map (Figures 11d & 11e) not only does not refer personally to the tested client, but whether it is not in conflict with the genealogical data. In other words, it becomes unclear why Ancestry.com does not explain to clients the methodology of mapping ethnicity in the different chronological spans and how these maps relate to the specific genetic results of the clients.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

Discussion and Considerations

The samples gathered specially for this project provide very interesting results for understanding of the limitation and delimitation of the current DNA research on the genetic origin of living individuals.

Autosomal Method and Close Relatives

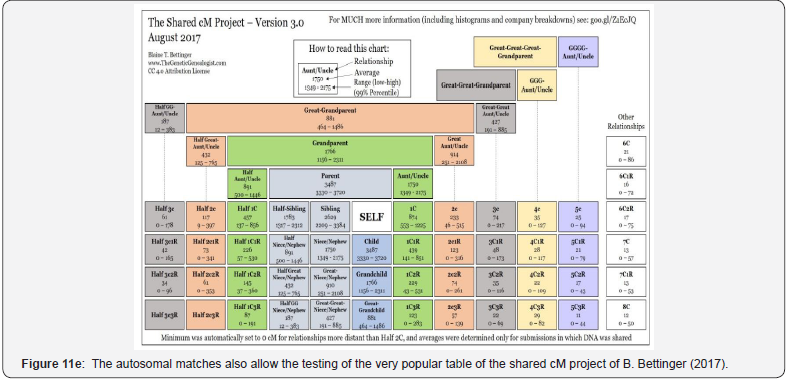

Revealing close relatives is the strongest aspect of genetic genealogy. As the samples above show, not every person’s test revealed close relatives. In one case (UE011959), the genetic match resulted in revealing a relative who had been unsuccessfully sought for years-a Bulgarian immigrant in the U.S. in the early 20th century. In another case (JK4589678), the closest relatives were unknown to the participant for years because of the broken links with the homeland. The autosomal matches also allow the testing of the very popular table of the shared cM project of Bettinger [7].

Two of the samples referred to close relatives. S.S. is a second genealogical cousin of UE011959, while FamilyTreeDNA refers S.S. as a 3rd-4th genetic cousin. According to the table of B. Bettinger, the average shared cM value for a 2nd cousin is 233, although the lowest possible values go down to 46 cM. Since the average value of S.S.’s match with UE011959 is between 3rd and 4th cousin, the attribution of FamilyTreeDNA can be translated into scientific language as 3rd-4th genetic cousin based on the average cM match, with an opportunity to reveal a 2nd genetic cousin, the lowest cM values of which overlap with the average cM values of a 3rd-4th cousin. The relative J.V. is a first cousin of UE011959’s father, or, in the words of the corrected Ancestry.com determination, a 2nd cousin, 3x removed (9 degrees) (Figure 1b).

Genetic and Genealogical Matches

The matches of the DNA samples based on centiMorgans define the so-called genetic “cousins”, that is genetic matches. However, genetic cousins may not always be genealogical cousins. In this work, a multi-crossing method was developed according to which the DNA data were compared to genealogical data and hypotheses and/or with family narratives about origin (through interviews). In several cases, the shared genetic data allow one to at least to make a guess about whether the maternal or the paternal sides were documented. For instance, participant FF765434 has well-documented dual origin (paternal side in Macedonia and maternal side in Slovenia), which was also very well documented as a general picture by Ancestry.com. Although the ethnicity of FF765434 and IG675479 is illustrated with completely identical maps of the northwestern Balkans and southern Europe in the past, IG675479’s reflections about her origin match the dual general picture. In other cases, genealogical data from the genetic matches stimulate future searches. For instance, the intersection of the data for UE011959 with individuals who have roots in Croatia may show that the maternal side was documented, the origin of which was in Macedonia. Accordingly, the distant cousins also may create a framework for consecutive genealogical research to verify or reject possible relatedness between distant “cousins.”

Ethnicity and Genetic Genealogy

The ethnical origin is one of the most attractive but least developed aspects of DNA testing, for the time being. It is a metaphorical “baby in the cradle” when it comes to methodology type, thereby requiring very solid background for the receivers of the results to understand the results. The key problem is the statement of “Story for”-that is, the statement that the ethnical maps tells the story of the tested individuals [2]. Despite this statement, none of the maps is explained as a procedure based on grounded theory and as a map applied to a specific individual. People who do not have anything in common from a genealogical perspective (IG675479 and FF765434) received identical ethnical maps that were even described with different ethnicity. Another problem of the general ethnicity maps [2] is that they have no chronological layers of origin before 1700, while the scientific criteria for the chronological layers 1700-1850/1900 are not well determined. The chronological ethnical makeup maps are general models that do not display direct relationship with the tested individuals.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

Scientific Applications

Terminology

The systematic analysis of the data allowed us to advance the theory of genetic genealogy by developing the terminology’s progress toward more correct and precise terms. It was proposed that, instead of “ethnicity,” the term “genetic identity / origin” better represent the results of the DNA testing, and instead of “cousin,” “genetic matches” is preferred.

Comparing results for a single participant whose DNA was tested by different companies infers that the “ethnicity”/origin conclusion are very loose in terms of the grounded theories. The difference in the results is due to the diversity of the genetic data and the absence of a developed methodology implementing a diachronically articulated view. Instead, a deep diachronic view is used, whereby the participants receive a flattened view. For this reason, the difference may simply indicate different chronological spans of the analyzed data. Most critical are the “ethnical maps” titled “Story for” (with the name of the client inserted in the blank). The maps, which do not include the genealogical data of the participant, are either incomplete or, in some cases, completely misleading.

Learning and Acquisition Parameters

The research results have extremely valuable learning and acquisition parameters because they shape the main body of case studies and examples in the modules of the curriculum. Among the learning benefits is a well revealed limitation of the genetic approach, the peculiarities of the differences between the genetic testing companies, and the ability of the students, through strong case studies, to understand the genetic results and the similarities and differences between autosomal DNA and mt-DNA (this case study).

Scientific Perspectives

The scientific value of the research results is a contribution to both the theory and methodology of cultural genomic studies, genetic genealogy, and to the interpretation of the genetic data from the perspective of genetic genealogy. The critical comparative analysis of the DNA sample results for genealogy revealed pros and cons in the way the data were delivered to the clients and in the way the data was interpreted. Most valuable are the data regarding shared cMs in the autosomal DNA tests. However, the use of the term “cousin” is vague and misleading since it includes not only cousins but aunts, uncles, and more distant indirect relatives. The term “cousin” was replaced in this work by “genetic match,” specified as close (CGM) or distant (DGM).

It was also revealed that “Story for” is misleading and needs to be replaced by “Reference to the Story for” by including reference data updated with the individual data from the test and from the matches. The way it is presented now is not only misleading, but it also breeds disappointment and distrust in the genetic data since everybody wants to know about his or her own cultural identity from the perspectives of the grounded theory, not pseudogrounded theory. A huge limitation in the implementation of the DNA test for scientific research is the fact that the companies do not provide the names of the responsible employees for reported results. Science has been made by people, not by companies and institutions. Absence of personal responsibility creates great opportunities for misleading conclusions and models and decreasing the trust in such important branch of genealogy such as genetic genealogy.

Cultural Perspectives

The cultural perspectives of the results are enormous. The research shows the borderless opportunities of genetic genealogy to enrich one’s individual cultural identity as a present network of relatives and by discovering many new relatives, as well as representing a problem of origin. The genetic data and genealogical data interact to paint a much more detailed and articulated picture of an individual’s past as it is embedded in the thousands of years of human history.

Sociological and Anthropological Perspectives

Sociology studies people through social structures while anthropology studies society through group and individual cultural and social identity. Genetic genealogy covers mostly modern and contemporary society from a historical perspective, but ancient DNA also creates unique opportunities to build models of ancient society through the genetic connections revealed between ancient populations. The research results of mt-DNA, with numerous analogies in the British Islands (FamilyTreeDNA results), may have traced even very ancient movement from the Balkans to the British Islands and North/Northwest Europe, which archaeologically are typically connected with Neolithization. However, the dynamics of female haplogroup T is very complex, meaning the similarity in the distribution may reflect more complex processes, the research of which is complicated by the absence of a satisfactory number of samples from all parts of Eurasia. Most curiously, Ancestry.com deleted this part of “The story for” section and replaced it with much more ambiguous statements about eastern Europe with a map spread over all of Eurasia. The research results in this work also showed that genetic genealogy gathers a huge database for anthropological research of kinship and society, migrations, mutations and health, etc.

Social Perspectives

The research results include very impressive examples of how genetic genealogy connects unknown relatives by discovering close genetic matches. Despite the misleading “cousin” terminology, it also confirms the kinship relationships of nephews / nieces and uncles/aunts through very impressive examples. Genetic genealogy may also confirm the dual origin of the test participant’s parents, coming from distant places or located in the same place.

Global Perspectives

Genetic genealogy is a global science from the point of view of origins. The example with migration from Spain/Portugal to Cuba in this study is complemented by migrations of Bulgarians to the U.S. in the early 20th century. Another great example is the deep roots of the human civilization [10]. However, the individual migration of ancestors and lineages require a specific scientific methodology in compare of general study of the immigrations in the words. Genetic genealogy is dedicated to the personal origin and mixing two different levels of scientific approach is a serious limitation of the current genetic results for genetic genealogy.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

Final Considerations and Conclusion

The results of the especially gathered samples provide primary sources for case studies and explanation of the basic concepts in the genetic genealogy. The participants in DNA tests had a diverse background, so the problem of origin was pictured globally. The results of testing of one and the same participant from different companies revealed the need of development of expertise in interpretation of the genetic data for origin to understand the data correctly. Mt-DNA test demonstrates the peculiarities of the main aspects of genetic approach to genealogy.

Origin is the main construct of the individual cultural identity. DNA tests provide unique data, although their interpretation for the time being, are in many cases not based on following the basic principles of the grounded theory. Instead “Story for” the companies mostly offer Reference to Story for”. The ideal model of personal origin is DNA tests interpreted from the perspectives of grounded theory in combination with traditional genealogical data and archaeological data for deep ancestral ancient origin. For the time being, the DNA test companies offer mostly general maps of origin (autosomal DNA tests), or in cases when more specific data are available (Haplogroup Ta1aL) are missing individualized interpretation.

The study of personal genetic origin is at a very beginning stage in compare to the DNA results on health [10] and requires collaboration of scientists and practitioners for development a strong trustful methodology.

- Research Article

- Abstract

- Research Sample: DNA Test Results for Genealogical Purposes

- DNA Tests for Genealogical Purposes

- Bulgarian Roots of UE022018

- Results of Participants Tested through the Same Company (Ancestry.com)

- Discussion and Considerations

- Scientific Applications

- Final Considerations and Conclusion

- References

References

- Ancesry.com (2018) DNA.

- 23 & Me (2018) DNA genetic testing and analysis.

- Family Tree DNA (2018) DNA tests.

- Helix (2018) DNA tests.

- Bettinger B (2016) The Family Tree guide to DNA testing and genetic genealogy. Cincinnati, OH: Family Tree Books.

- Bettinger BT, Wayne DP (2016) Genetic genealogy in practice. USA: National Genealogical Society.

- Bettinger B (2017) August 2017 Update to the Shared cM Project. The Genetic Genealogist, USA.

- Nikolova L (2018) ScholaSrly Branches in 21st-Century Genealogy (Earliest 19th-Century Bulgarian Immigrants in the US at ancestry. com). Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences 1(6): 1-10.

- Nikolova L (2018) Genetic genealogy as an emerging research branch of human ancestry and origin (Review of curricula and other learning sources). International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education 5(3): 169-183.

- Nikolova L (2018) Cultural genomics and the changing dynamics of cultural identity. Nova Science Publishers, New York, USA.