The Former Quarries in Vapolicella-Architectural Perspectives between Landscape Re-Use and Local Identity

Gerardo Semprebon1, Luca Maria Francesco Fabris2 and Wenjun Ma*3

1 Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Politecnico di Milano, Italy

2Politecnico di Milano, Italy

3 Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Italy

Submission: August 30, 2018; Published: September 20, 2018

*Corresponding author: Ma Wenjun, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. Email: mwj@sjtu.edu.cn

How to cite this article: Gerardo S, Luca M F F, Wenjun M. The Former Quarries in Vapolicella-Architectural Perspectives between Landscape Re-Use and Local Identity. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 6(5): 555696. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.06.555696

Abstract

Considering the recent studies focused on the landscape design in the marginal areas, this paper deepens the former quarries in Valpolicella, a scenic area in the nearby of Verona, Italy, conceived as a remarkable case-study to investigate the correlations between abandon sites and local identities. Assuming the perspective of landscape architecture’s studies, the paper aims to highlight topics and relevant issues related to recycling practices for the former quarries, drawing up the state of the art related to their spatial framework, as well as their socio-economic implications. The authors performed their investigations recalling the literature review, the selection of significant theretical contributions, and the on-field investigation. Although some academic results related to the study of mining and quarries’ sites have already been achieved, the authors find there is still a gap between the awareness of quarries’ conditions and the ability of proposing effective strategies of rehabilitation for such places.

Keywords: Quarries; Stone industry; Identity; Valpolicella; Verona; Landscape reuse; Architectural design

Introduction

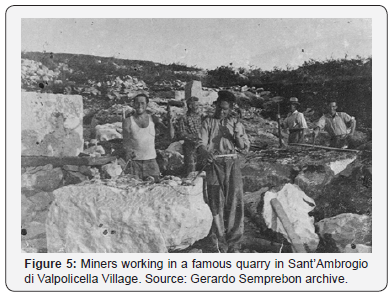

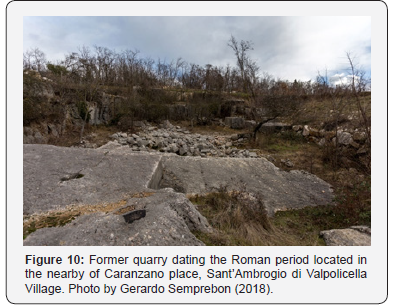

In the Rapporto Cave 2017, the association Legambiente draws the Italian situation, declaring that on the total amount of 4.752 active quarries, 388 are in Veneto region, with 69 within Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo [1], a village in Valpolicella (Verona) (Table 1). The Valpolicella’s stone industry has been working over centuries the red ammonitic limestone, the Rosa Corallo stone, the Bronzetto stone and the Pietra della Lessinia stone. The use of such materials is documented in many civil and sacred buildings of not only Verona’s area. Indeed, it is widely known that some blocks of stones used for the construction of the Roman amphitheater the Arena of Verona come from the red ammonitic limestone’s quarries of Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella, where the transportation could benefit from the presence of the Adige river, which flows in the nearby of the Roman Via Claudia Augusta. The same stone was chosen to realize the lions of the medieval churches of Modena, Bergamo, and Parma. The mining activity and the stones’ production spread over centuries influencing and interfering with the people and communities living in Valpolicella, shaping the social and economic premises which still permeate the territory. The know-how rising from the stones production led the population benefiting from an ever-increasing working demand both from inside, as the stone’s architecture of San Giorgio Ingannapoltron hamlet well shows, and outside the country, as demonstrated by the military fortifications realized during the Austrian domination (Figures 1 & 2).

In 2003 the Veneto region adopted the Piano Regionale di Attività di Cava (Quarries Activities’ Regional Plan), a document regulating and coordinating the extraction of stones, the environmental repairing, the quarry’s activity optimization, and the surveillance activities intensification. Recently, as specified by the Rapporto Cave 2017, the lack of effective industryrelated planning, encouraged the spreading of illegal practices, producing a considerable surplus of extraction sites, beyond the real market’s demands, which today, in the current framework of mining industry crisis, turn into a large amount of dilapidated and abandon quarries [1]. In consideration of such sites, this manuscript aims to draw the state of the art related to their spatial framework, as well as their socio-economic implications. Although some academic results related to the study of mining and quarries’ sites have already been achieved, the authors find there is still a gap between the awareness of quarries’ conditions and the ability to propose effective strategies of rehabilitation for such places. Assuming the perspective of landscape architecture’s studies, the purpose of this manuscript is therefore to highlight topics and relevant issues related to recycling practices for the former quarries. The productions’ reasons, which cause the sites‘ physical modifications and the territory’s depletion, merge indissolubly with the social and cultural repercussions, since the working opportunities contributed to forging the sense of belonging and the collective imagination.

The same for historical and heritage circumstances, which witness the abundant use of local materials as primary resources to realize important constructions, interfere with artistic aspects, through the strengthening of local technologies and figurative expressions. Moreover, there is an urgent need of securing the territory to prevent severe damages, or even casualties, in case of catastrophic events or other accidents (Relazione Ambientale del Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Provinciale di Verona, 2007). However, the standard procedures for environmental recovery and compensation, usually show little sensibility to the identity features permeating a territory which has been forged by a centuries-old economy based on stones extraction and production (Figures 3-5).

The Quarries Today: Morphology and Perception

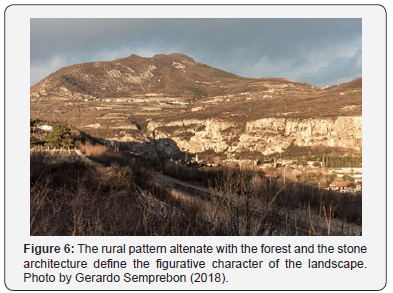

The Valpolicella is a foothills area extending from the north of Adige river to the slopes of Monti Lessini. Zorzin & Cacciavillan [2] report that «along the ridge of Monte Pastello it is evident an intense extracting activity of stones, due to the advantageous orientation of the outcropping layers and to the quality of the present materials». Such activity consolidated over the years and deepened in the production of marble industry and ornamental stones. The intense activity caused the pit faces to have considerable sizes, even dozens of meters, and to strongly impact on the scenic landscape, featured by forest masses, submediterranean vegetation and small human settlements (Figures 6 & 7). The quarrying activity shaped the territory by modifying its form and, at the same time, changing its perception, through the removal of trees from the hills’ slopes.

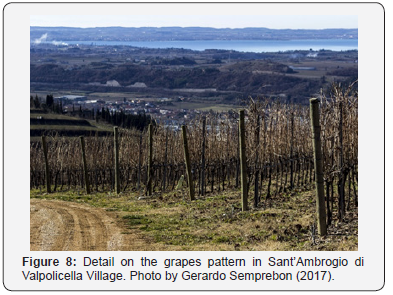

The rocky layers emerged from the greenery, coming visible even from far away and became part of the landscape. Such signs impressed in the landscape represent, for better or worse, the trace of human activity on his territory, in a similar way as for rural activity, whose impact is less recognizable just because the transformation cycles are extended to a broader time span. Therefore, quoting André Corboz [3] we can address the territory as a human product (Figures 8 & 9). Popular thinking is that the pit faces of an abandoned quarry are hostile witnesses of the reckless behavior of man towards his own natural environment. Hence, the former quarries underwent a negative layer of meaning and perception, making the abandon sites edge zones in/of the landscape [4], forgotten and repudiated by the community. Although the reasons for such process are heterogeneous, it is possible to find some clues in the fragmentation of the land-tenure regime and right use and in the incapacity by the tourist industry to imagine any rehabilitation scenario.

Indeed, the tourist market is mostly concerned with the local winery industry, which, conversely, has benefited from the mining sites’ divestment, since, where possible, a considerable amount of land has been converted to the grapes cultivation, exacerbating the issue of monoculture in Valpolicella. Furthermore, the confusion existing between the notion of nature and the one of landscape, frequent in the ecologist thinking, represents one of the main obstacles for a truth awareness about what is the meaning of landscape and territorialization. Eugenio Turri, who was a distinguished local geographer and who wrote insightful pages on the local territory, reveals that «the landscape of Monti Lessini has, as its main feature, the essentiality. This means that it (the landscape) is entirely expressed by the things that give shape to it, nothing is superfluous or non-functional to its being, to its expression» [5].

The Former Quarry’s Site: from Drosscape to Potentiality

Recent academic achievements [4,6] reveal the unexpressed potential of former mining sites, as occasions for new design morphologies. The theme of the landscape’s construction has a twofold value according to its double essence, given by the combination of the environment-topographic evolution with the formal-technical setup produced by the human activity. The understanding of the landscape’s construction can be conceived as the reading of a human affair, as the interpretation of a narrated or represented novel [7], most of the times, targeted to improve the production [8]. It is authors’ opinion that the first step towards the redemption of the former quarries in Valpolicella consists in the attribution of an aesthetic value free of the past irreversible inheritance. Moreover, since it is not possible to pursue any idyllic or primordial state of purity only ideally untouched by man, it is necessary to assume a dynamic perspective, with the awareness that we are in the middle of a process of continuous transformation in which man and his habitat are tied by an unbreakable symbiotic relationship. The designing approach postulated by Vittorio Gregotti and by Anrdè Corboz represent an indispensable methodological step to face the project for the rehabilitation/recycle/reuse of former quarries.

The word project, from the latin pro-iectare (literally to throw forward) assumes in the work of the two authors an aest-ethic meaning (literally beyond ethic) able to clarify the semantic aspects that link, and at the same time free, the future from the past, the abstract drawing from the real world, the collective imagination from the tangible condition. Corboz states that territory and project coincide, while Gregotti explains how the responsible designer, or the architect, or the planner faces the freedom of the project, stating that the freedom has to be conceived as project and as value [9], as a grafting in the memories of the place. The project judges the current condition permitting to escape the pure descriptive categories e to rehabilitate the ground, which, far from being just a shapeless medium, contains, forms and structures the territory [10] (Figures 10 & 11).

A Thematic Re-Articulation

The design stage follows a phase in which it is worthy to define the theoretical tools. Such premises represents a necessary step, even if strictly context-related. We want to report three academic achievements considered relevant both for the case of Valpolicella’s quarries and for comparable counterparts. First, within the notion of landscape we can find two main meanings: the one of territory, with its spatial and geographical component, and the one of environment, with its biological, historical and cultural elements. In a well-know editorial in 1982, Gregotti [11] states that the built-up environment surrounding us is the physical way of being of history, the way it accumulates, through different thicknesses and meanings shaping the uniqueness of the place. Reading and interpreting the territorial and the environmental reasons become a crucial premise for any conscious and free design action. Another key-assumption raises from the work of the philosopher Nicola Emery, who, by elaborating the findings of Heiddeger [12-15], emphasize the ethic role, almost therapeutic, of human dwelling, conceived as taking care of the place. Such position suggests the adoption of design strategies targeted of blossoming bottom-up microtransformations, where it seems easier to converge the interest between private and public realm, under a single directorship.

On the other side, we propose the vision of Alain Roger, who encourage an aest-ethic approach, beyond the Emery’s ethic. The so-called artialization in situ and in visu represents a possible key-angle to re-read and re-mean such places which underwent negative impacts, like the former quarries. The cultural action on the object, either natural or artificial, can promote a new approach targeted to reveal the richness of a territory that is defined by an endless continuous modification’s process, by exploiting the local resources. The provocation according to which the world has been created as many times as an original artist was able to imagine it, confirms Roger’s attitude and stress the inadequacy of a position which still fosters the coincidence between nature and landscape, as a starting and ending point of the human affair on the Earth. Following such perspective, the former quarries can re-boot a new production cycle, not of stones, but of cultural contents, aiming to encourage a semantic shifting.

Conclusion

This manuscript is articulated in two parts. The first describes the Valpolicella’s quarries as remarkable case-study for landscape design in relation to the topic of abandon sites and local identity. Starting from historical and quantitative considerations, we proposed a cultural framework, defining weaknesses, potentialities and the common practice. In the second part, the manuscript deepens the main landscape design issues risen from the on-field observation, in order to make generalizations applicable to other contexts, with the awareness that universal solutions do not exist. This manuscript represents a first attempt to bridge the gap between the awareness of quarries’ conditions and the ability of proposing effective landscape design strategies of rehabilitation, through the formalization of a context-related state of the art. The case of Valpolicella’s quarries becomes a demonstration sample for those sites which are facing phenomena of depletion and abandon, where imagining reactivation practices requires challenging thinkings, both in term of cultural background and in and in design solutions. The architectural project assumes a diachronic dimension, becoming a process, at the same time occasion for knowledge and future prefiguration. Facing this moment of suspension, the paper concludes with three thematic nuclei upon which the contemporary landscape design projectprocess can structure its design strategies.