New Methodologies for Human Movement Analytics: From Engineering Principles to New Health Science

Aleck Alexopoulos*

Centre of Research and Technology Hellas, Thermi, Greece

Submission: April 23, 2025;Published:May 08, 2025

*Corresponding author:Aleck Alexopoulos, Centre of Research and Technology Hellas (CERTH), 6th kn Harilaou-Thermi rd., Box 60361, Thermi, Thessaloniki 57001, Greece

How to cite this article:Aleck A. New Methodologies for Human Movement Analytics: From Engineering Principles to New Health Science. Eng Technol Open Acc 2025; 6(3): 555690.DOI: 10.19080/ETOAJ.2025.06.555690

Abstract

The assessment of human movement is of immense importance in areas such as sports, active living, and numerous health and medical applications. Existing approaches, such a gait analytics, are either limited in scope or require special equipment. What is needed is a deeper and more comprehensive movement evaluation system that can be implemented with minimal equipment. Here we report on a first-principles approach based on engineering principles that leads to a human movement model which can evaluate the current condition of a subject in terms of movement and functional capacity in a much deeper and objective manner than current simple tests.

Keywords:Engineering; Artificial Intelligence; Glycogen

Introduction

The importance of human movement has become prevalent in many areas in the last decade. In the area of Sports Science movement analytics have been developing rapidly with the appearance of advanced biomechanical models [1], introduction of metabolomics and genomics [2], and has been further empowered by the introduction of numerous new techniques for measuring movement and performance in general [3]. However, in terms of analysing the current condition of athletes and then designing personalized training programs that can enhance their performance, very little progress has been achieved and mostly in the area of endurance sports [4-6]. In resistance training much less, progress has been achieved [7,8].

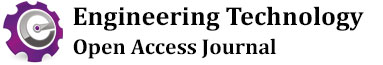

Here we report a computational approach that integrates sub-models for energy consumption and velocity-dependent force development following established engineering principles. Additional elements such as fatigue and post-movement recovery can be included via a micro-scale model of muscle fibers that considers both available fuels (e.g., ATP, creatine, and glycogen) and different fiber types (Figure 1). These types of multi-scale models are common in Engineering disciplines, e.g., Chemical and Materials Engineering.

This type of computational approach leads to a system of equations with physically meaningful parameters specific to the individual which could be considered as subject specific movement metrics. In order to determine the values of these parameters for a specific movement (e.g., sit-to-stand) and subject multiple movement tests are required. The series of movement tests must examine different limitations to movement (e.g., maximum force, force-velocity relationship, strength endurance, fatigue, strength recovery, and power). Furthermore, the movement tests must take into account the limitations and expected functional capacities of the subjects which will differ greatly (e.g., between amateur and professional athlete or between young and old subject, or between healthy and frail individual).

It should be noted that while the use of AI models can be effective in developing solutions there are some limitations in their capability for assessing human movement. One limitation is that a training individual will adapt and change faster than a neural net can learn based on training data. However, classification of subjects based on their multidimensional movement metrics is certainly a possibility. Another limitation is that when a fundamental understanding of a system is lacking essential data may be missing without the researcher (and the AI) knowing that data is missing. In such cases no current AI can solve the problem. However, if the aforementioned first principles movement model is developed the movement metrics it provides could provide sufficient data to an AI model.

The movement metrics established by this approach provide the subject’s functional capacity for the specific movement. For medical applications this is important information especially if combined with additional information (e.g., biological or digital biomarkers) explaining the limited functional or movement disorder [9-12]. Depending on the medical cause these data could include for example: stress (via SGR), muscle synergies (via EMG), neuromuscular activation (via EEG).

Conclusion

The use of first principles engineering principles can lead to movement models that can be of great benefit to movement and functional capacity assessment. By developing the fundamental knowledge missing in human movement assessment, one can then identify the type of missing data, and actually solve the model with or without the assistance of AI models.

Applications in Sports include evaluation of athletes, optimal personalized training programs, and monitoring of rehabilitation. In medicine, several conditions require the assessment of the functional capacity of the patients (e.g., sarcopenia, frailty). This modelling approach can empower healthcare practitioners by correlating movement metrics to other biological and digital datasets (e.g., stress, EMG, EEG, PRV) in order to determine also the potential causes for limited functional capacity or movement dysfunction.Finally, in space missions microgravity induced muscle wasting and bone resorption require more optimal and personalized training and assessment solutions that can be integrated with other mitigation measures for cardiovascular and neurological effects. This has become of paramount importance in anticipation of long duration missions beyond low-Earth orbit [13].

References

- Yeadon MR, Pain MTG (2023) Fifty years of performance‐related sports biomechanics research. Journal of Biomechanics 155: 111666.

- Sellami M, Elrayes, MA, Puce L, Bragazzi NL (2022). Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 8: 81540.

- Luczak T, Burch R, Lewis E, Changer H, Ball J (2019) State-of-the-art review of athletic wearable technology: What 113 strength and conditioning coaches and athletic trainers from the USA said about technology in sports. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 15(1): 26-40.

- Clarke DC, Skilba PF (2013) Rationale and resources for teaching the mathematical modeling of athletic training and performance. Advances in Physiology Education 37(2): 134-152.

- Kolossa D, Bin Azhar MA, Rasche C, Endler S, Hanakam F, et al. (2017) Performance Estimation using the Fitness-Fatigue Model with Kalman Filter Feedback International Journal of Computer Science in Sport 16(2): 117-129.

- Imbach F, Sutton‑Charani N, Montmain J, Candau R, Perrey S (2022) The Use of Fitness-Fatigue Models for Sport Performance Modelling: Conceptual Issues and Contributions from Machine-Learning. Sports Medicine- Open 8: 29.

- Banister E, Calvert T, Savage M, Bach T (1985) Development and Validation of a New Method to Monitor and Control the Training Load in Futsal: the FUTLOC Tool. Australian Journal of Sports Medicine 7: 57-61.

- Zatsiorsky VM, Kraemer WJ (1995) Science and Practice of Strength Training. 2nd (edn.), Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, USA.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, et al. (2010) Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age and ageing 39: 412-423.

- Koo BK (2022) Assessment of Muscle Quantity, Quality and Function. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome 31(1): 9-16.

- Patterson, TL, Mausbach, BT. (2010) Measurement of Functional Capacity: A New Approach to Understanding Functional Differences and Real-World Behavioral Adaptation in Those with Mental Illness. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 6: 139–154.

- Martin FC, Ranhoff AH (2021). Frailty and Sarcopenia. In: Falaschi P, Marsh D (eds.), Orthogeriatrics: Practical Issues in Geriatrics. 2nd edn, Cham, Springer, Switzerland.

- Kittanawong C, Nithin KS, Richard AS, Emmanuel U, Eric MB, et al. (2023) Human Health during Space Travel: State-of-the-Art Review. Cells 12(1): 40.