Is the thobe a Symbol of Radicalisation of Gen Z Muslim Men?

Jamal Majid*

Manchester Fashion Institute, Manchester Metropolitan University, United Kingdom

Submission: July 05, 2023; Published: July 28, 2023

*Corresponding author: Jamal Majid, Manchester Fashion Institute, Manchester Metropolitan University, United Kingdom, Email: j.majid@mmu.ac.uk

How to cite this article: Jamal M. Is the thobe a Symbol of Radicalisation of Gen Z Muslim Men?. Curr Trends Fashion Technol Textile Eng. 2023; 8(4): 555742. DOI: 10.19080/CTFTTE.2023.08.555742

Short Communication

The thobe is an ankle-length robe which has long sleeves, worn by Muslim men to ensure that they are appropriately dressed in modest fashion for Islamic prayer, which observers of the faith are obliged to practice five times per day. The author has reflected on his own experience and has observed that in a university environment the instance of male students embracing the thobe has increased dramatically over a period of recent years and this small-scale inquiry seeks to at least attempt to understand the phenomenon of why male students typically between the ages of 19 to 22 are choosing this form of apparel, especially in an environment in which Muslims are the object of so much negative media attention.

In order to ascertain the reasons for why young men studying at the Manchester Metropolitan University (Gen Z) are choosing to embrace the thobe a series of semi-structured interviews were conducted in conjunction with approaches of reflection, were embraced to reflect on this apparent increase of Muslim students embracing such garb. The likes of John Dewey and then by SchÖn in the latter part of the twentieth century advocated that thinking whether it be in refection or in action is beneficial as it serves to be a mechanism for the improvement of standards and robust reflective analysis, in order to understand phenomenon in greater detail [1]. The use of such a model in respect of reflection in relation to the instance of male students in particular embracing the thobe can be beneficial as it not only has manoeuvrability to embed elements of research tools from a variety of methodological stances but is also consistent to the authors personal epistemological values.

The bias media discourse and consistent sensationalising of the Islamic faith with criminality, radicalisation and terrorism in conjunction with false information within the western media, would suggest that the Muslim community may be more amiable to avoid outward display of religiosity in order to avoid discrimination. Especially, when considering that hate crime against Muslims and rise of far-right movements directly opposed to Islam have increased not only in Britain but arguably throughout the western world [2]. This is evident in countries such as France and Denmark where right-wing political factions have successfully banned Islamic religious female garb religious and other forms of religious apparel altogether [3]. Indeed, American research institutes the likes of Zogby Analytics and the Pew Research Centre revealed in their opinion polls that Arabs and Muslims have the lowest favourability ratings among religious and ethnic groups accompanied with the coldest feelings from the public in general [4]. Independent research emanating from 2018 onwards uncovered that public opinion was influenced by media amplification and bias indeed almost sixty percent of the articles and forty-seven percent of the television content associated with Muslims/Islam being portrayed negatively [5]. Additional case studies undertaken also advocated how Muslims are misrepresented, defamed and labelled in major British publications (The Times, The Independent), with damages and public apologies having to be given in all but one instance (Ibid).

One would assume that such overt animosity towards less than five percent of the British population would surely warrant more conformity? Indeed simulation to western values which is arguably easily identifiable and achievable with the embracing of more western apparel in order to disassociate oneself from notions of radicalism or repression, [6]. However, Piela et al. [7] contends that the opposite is happening, resulting in a situation in which more young women are increasingly choosing to wear a headscarf (hijab) and young males are choosing to grow beards and embrace traditional Islamic attire (Thobe).

Within modern day Britain rather than a tool of repression some academics have advocated that it can been seen as a symbol of expression and strength - as the embracement of religious symbolism, irrespective of items of clothing such as the thobe, undoubtedly leave one open to physical and verbal abuse. Hence, whys is there an increasing confidence, especially amongst the Muslim youth to display their religion in a more overt manner, surely warrants some greater reflection in order to further our understanding [8].

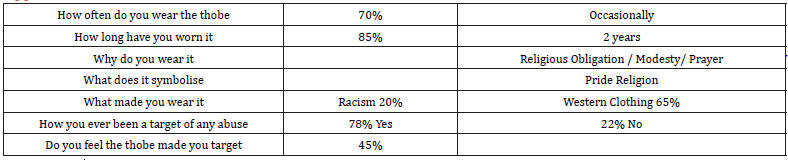

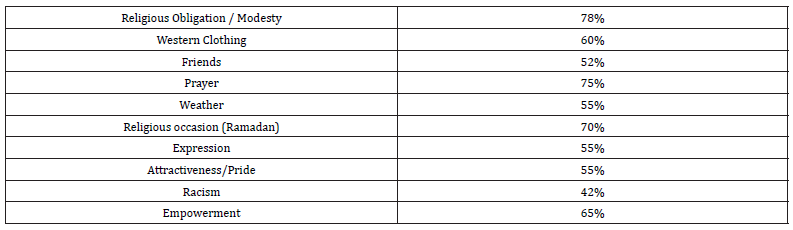

The ten semi-structured interviews and subsequent five focus groups undertaken comprised of six unambiguous questions in order to generate the discussion, (Appendix 1). It is acknowledged by the author that the more value laden, interpretive or indeed phenomenological lines of the inquiry, the greater the likeliness for the study to include ‘open ended’ questions, in order to develop a more informed and meaningful response in relation to the enquiry into the thobe. This was considered to be beneficial as it could uncover greater insight and alternatives avenues of thought which may have never been considered [9]. The results of which were correlated to a rational scientific coding which uncovered ten key areas being identified [10].

The result of the investigation reveals that the reasons to embrace the thobe were routed in multiple areas. This complements the very notion of fashion itself in which fundamental style standards are diverse and complex, whether it be driven by cultural, religious, or indeed aesthetic reasons [11]. Some of the reasons for wearing the thobe also appeared to be contradictory and some of which could be construed as dichotomous. For instance, it was uncovered that racial slurs/attacks resulted in seeking to associate more with the religion and facilitated wearing the thobe rather and dissociation. The results also uncovered that religious occasion (Friday Prayer’s and Ramadan) and educations by peers served to be key facilitators, especially in a university setting in which a more varied and diverse peer groups were formulated, resulting in actually ignited the desire to experiment with apparel such as the thobe. Racism did in some instance (42%) serve to be the conduit to ignite the introduction of the thobe to the wardrobe. However, more simplistic and surprising responses such as, hiding large stomachs and looking more attractive were more prominent responses. Hence, the ability of modest apparel such as the thobe has to facilitate a more aesthetic body image, could be a factor which serves to heighten its appeal [12].

The instance of sixty-five percent of recipients advocating that the thobe serves to be a tool of empowerment, reflects the fashion industries interpretation of this phenomenon. The more recent tone of the of the fashion industry is that modest clothing should not only be viewed by satiating religious needs, but should also be viewed as a tool for self-empowerment, which is why the modest clothing market is predicted to grow to in excess of three billion dollars in 2024 [13].

It was also uncovered that seventy eight percent of the students highlighted that religious obligation to be modest, especially when in prayer was the prominent response to question three, rather than any radical counter expression to western values or its way of life. However, it is acknowledged that the presence of the researcher could have mitigated any such response [14]. A key factored identified by the research was the fit of western clothing, sixty percent of the study advocated that the thobe could be an easy item of apparel to cover up tight jeans with low rises and other items of apparel such as sportwear which has a tighter/structured fit (Appendix 2). Hence, it could be suggested that the thobe could also be an item of convenience to complete religious obligation rather than a symbol of religiosity or indeed any overt defiance or deference to western values of experienced racism. Hence, retailers, who focus on this younger demographic should potentially expand their product ranges offering more of a diverse range of modest clothing collections for Generation Z and Millennial, in order to capitalise on this growing market [15]. With the likes of prominent fashion magazines (GQ Magazine) seeking to tapping into the movement of modest clothing, featuring thobes complemented with luxury apparel from Balenciaga trainers to Louis Vuitton jackets indicates its introduction to the mainstream could be profitable [16].

Conclusion

The impact of the research although small scale does suggest that there could be a potential rise in the demand for more modest apparel such as the thobe. Despite Modest Fashion emerging in the early 2000 within the Middle East this market potential has still not been harnessed [17]. Hence, there may be an opportunity for fashion brands to incorporate a modest capsule edit or modest silhouettes which will not only serve to widen fashion retail appeal to a wider segment of the population, but also be a tribute to greater inclusivity to a demographic with greater spending power [11]. Some brands the likes of H&M have experimented with such ranges [18], but the interpretation of Islamic or modest clothing warranted more investigation as it fell short on what to deliver to this consumer, as Modest fashion refers to clothing that is designed to cover the body in a more conservative manner in accordance with certain cultural or religious beliefs, rather than that of what mainstream retailers perceive to be as modest [19]. The gap on the market in conjunction with the instance of growing Muslim demographic (which is predicted to account for nearly a third of the world’s population by 2050) illustrates the real capital benefit this market potentially has [20-30].

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

References

- Roffey-Barentsen, Malthouse JR (2009) Reflective Practice In The Life Long Learning Sector. Exeter. Learning Matters Ltd.

- Miqdaad M (2016) The Independent Online “Why the British media is responsible for the rise in Islamophobia in Britain.

- Weaver M (2017) The Guardian Newspaper “Burqa bans, headscarves and veils: a timeline of legislation in the west European states have moved over the years to outlaw Muslim headwear in public.

- Chitwood K (2015) “‘Radical Muslims’ clothing line attempts to shatter stereotypes” The Washington Post - Religion News Service.

- Rickett O (2021) UK media report finds widespread anti-Muslim bias in press coverage. Middle Easter Eye.

- Haddad YY (2007) The Post-9/11 "Hijab" as Icon. Sociology of Religion. France Oxford University Press 68(3): 253-267.

- Piela A (2022) Muslim Women and the Politics of the Headscarf.

- Goldsmith B, Harris O (2014) Violence, threats, prompt more Muslim women in Britain to wear a veil. Reuter Online.

- Jonker J, Pennink BJW (2010) The Essence of Research Methodology: A Concise Guide for Masters and Phd Students in management Science. London, Springer Heidelberg Dorrecht.

- Cohen L, Manaion L, Morrison K (2007) ‘Research Methods Education’ Sixth Edition, Abingdon, Routledge.

- Herrmann V (2022) Why modest fashion is big business, Fashion Industry Data and a Point of-View.

- Justluxe (2022) How Do You Dress Modestly Without Looking Frumpy?

- Glamour (2022) Modest fashion is on the rise, so here are the best modest fashion brands to have on your radar.

- Colin R (2002) “Real World Research” Blackwell Publishers. London.

- Mintel (2022) Clothing Retailing- UK 2022.

16.Lambrat, M (2022) GQ Online the future is Ours - Mous Lamrabat Captures the Spirit of a Generation Living between Two Worlds.

- Omar S (2023) Modest fashion: From the hottest trends to the coolest brands, here’s everything you need to know, Glamour UK.

- Carder S (2018) “H&M has launched a new modest clothing line” Evening Standard. Insider Fashion.

- Benissan, E. (2021) Luxury Brands are failing to meet Muslim consumers – Hers’s Why. Vogue Business Online.

- Forbes (2021) On-Trend: Why Modest Fashion Is Both A Movement And An Entrepreneurial Opportunity.

- Baqarah (2023) What is modest fashion? A comprehensive guide to modest style.

- BBC (2019) Modest fashion: 'I feel confident and comfortable'.

- Bint-Abubaker R (2013) The Rise of the Muslim Fashion Industry.

- Darrin, H, (2018) A women is more than what she wears. The conversation.

- Goldsmith R (2006) Why and Who Wears Islamic Clothing? Fibre 2 Fashion.

26.Haris R (2016) D&G’s hijab range is aimed at people like me – so why do I feel excluded?

27.Khalil A (2013) Decoding facial hair in the Arab world. BBC Online.

- McKinsey (2022) The State of Fashion 2023: Holding onto growth as global clouds gather.

- Onikoyi O (2013) Why Radical Islam is Growing and How to Deal with It. London Progressive.

- WGSN (2023) Youth Priorities 2023.