Hedonic/Utilitarian Cool Attitudes: A Comparison of Young Female and Male Consumers

Mijeong Noh1*, Rodney C Runyan2 and Jon Mosier3

1Department of Human and Consumer Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, USA

2School of Family and Consumer Sciences, Texas State University, San Marcos, USA

3Global Marketing Partnerships & Promotions, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, Century City, USA

Submission: September 13, 2017; Published: October 03, 2017

*Corresponding author: Mijeong Noh, Department of Human and Consumer Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH, Tel: +740-593-2878; Email: noh@ohio.edu

How to cite this article: Noh M, Runyan RC, Mosier J. Hedonic/Utilitarian Cool Attitudes: A Comparison of Young Female and Male Consumers. Curr Trends Fashion Technol Textile Eng. 2017; 1(1): 555551. DOI: 10.19080/CTFTTE.2017.01.555551

Opinion

Young consumers are considered fashion innovators because they tend to accept, adopt, and use new products more frequently than any other consumer group. Young consumers are appealing to commercial apparel marketers because their purchasing power has increased over the years and their buying behavior can influence the acceptance or rejection/avoidance of new products within a few months after they are introduced to the marketplace [1]. Apparel marketers use the concept of cool as a marketing tool to stimulate young consumers to purchase. A cool lifestyle reflects consumers' desire for novelty. As such, marketers that develop profitable new cool products fulfill consumers' tastes for novelty. In general, consumers purchase products for both hedonic and utilitarian values in shopping venues [2]. Specifically, women tend to enjoy hedonic shopping more than men, who often shop only to accomplish an instrumental need and do not engage in "shopping for shopping's sake” [3]. Chang et al. [4] find that male shoppers tend to possess more utilitarian constructs for apparel shopping satisfaction than hedonic constructs. From these studies, we expect to find a gender difference in hedonic/ utilitarian attitudes toward purchasing cool clothing. Thus:

a. Hypothesis 1: Young female consumers exhibit more positive hedonic attitudes toward cool clothing than young male consumers.

b. Hypothesis 2: Young female consumers exhibit more negative utilitarian attitudes toward cool clothing than young male consumers.

Consumers' self-image can have a strong influence on behavior in the marketplace [5]. In particular, consumers' actual self-image is important to marketers because consumers seek out brands that match the self-image they want to project to others [6]. Noh & Mosier [7] find that young consumers with high levels of actual self-image are not interested in utilitarian values when purchasing cool products. As such, we suggest that young female consumers' actual self-image influences their hedonic attitudes toward purchasing cool clothing. Thus:

c. Hypothesis 3: Young female consumers' actual self-image is positively related to their singular hedonic attitudes toward cool clothing.

d. Hypothesis 4: Young female consumers' actual self-image is positively related to their personal hedonic attitudes toward cool clothing.

e. Hypothesis 5: Young female consumers' actual self-image is positively related to their aesthetic hedonic attitudes toward cool clothing.

This study examines the difference in hedonic/utilitarian attitudes toward cool clothing, between young female and male consumer groups and the causal relationship between actual self-image and hedonic attitudes toward cool products for young female consumers. To measure actual self-image, we used the Actual Self-Concept scales ( "e.g.,”l see myself in regard to being unattractive/attractive) [8]. We also employed the measurement scale related to the concept of cool (singular, personal, aesthetic, functional, and quality cool) [9]. College students enrolled in 11 different courses at a major US university participated in the main study. Of the respondents, 165 were women (62.3%) and 96 were men (36.2%). Respondents' ages ranged from 18 to 28 years, with a mean age of 21 years. Most of the respondents were Caucasian (63.0%). The majority of the respondents had an average family income of $67,500 with an average discretionary spending of $70.97 per week.

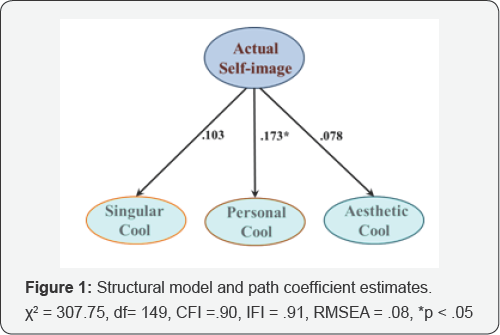

We employed multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and single-group Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to test the developed hypotheses. The MANOVA results revealed significant differences in the three hedonic (singular, personal, and aesthetic hedonic cool) attitudes toward cool clothing between the two groups (F=14.82, p< .001, partial χ2=.225), in support of H but not H2. That is, young female consumers are more likely to be in a hedonic than utilitarian mindset when shopping for cool products. We conducted single-group SEM with the maximum likelihood estimation to examine the hypothesized relationships (from H3 to H5). The results indicated that the proposed conceptual model had a significant chi-square statistic (χ2= 307.75, df= 149, p= 0.000), and other model fit indices also were below acceptable cutoff levels (CFI = 0.90; IFI = 0.91). However, the RMSEA was 0.08, indicating a moderate fit of the model [10]. Therefore, we assessed the path coefficients of the model corresponding to the hypotheses. As seen in (Figure 1) and the regression coefficient for the path from actual self-image to the personal cool attitudes was statistically significant. The SEM results indicate that young female consumers' actual self-image is positively related to their personal hedonic attitudes toward cool clothing. Therefore, the results provide support for H4 but not for H3 and H5. Young female consumers with a high level of actual self-image desire to purchase cool products to reflect their personality and individuality and to fit their lifestyles.

Young female consumers' actual self-image is a crucial factor to the success of cool clothing products; however, no studies have examined the relationship between this critical factor and hedonic attitudes toward cool clothing. These findings provide commercial marketers with some valuable information about young female consumers' purchasing behaviors toward cool products, which then allows them to develop strategies to increase sales of new products targeted to young female consumers based on a more in-depth understanding of perceptions of cool. The findings offer guidance to apparel commercial marketers in determining which hedonic cool products are congruent with their targeted young female consumers' actual self-image.

References

- Johnson L (2006) Mind your X's and Y's. Free Press, New York, USA.

- Babin BJ, Darden WR, Griffin M (1994) Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research 20(4): 644-656.

- Campbell C (1997) Shopping, pleasure and the sex war. In: P Falk & C Campbell (Eds.), The shopping experience. Sage, London, UK, pp. 166175.

- Chang E, Burns LD, Francis SK (2004) Gender differences in the dimensional structure of apparel shopping satisfaction among Korean consumers: The role of hedonic shopping value. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 22(4): 185-199.

- Ataman B, Ulengin B (2003) A note on the effect of brand image on sales. Journal of Product & Brand Management 12(4): 237-250.

- Schiffman L, Kanuk L (1997) Consumer behavior. (6th Edn), Upper Saddle River, Prentice-Hall, NJ, USA.

- Noh M, Mosier J (2014) Effects of young consumers' self-concept on hedonic/utilitarian attitudes toward what is "cool”. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 7(3): 163-169.

- Ericksen M, Sirgy M (1989) Achievement motivation and clothing behavior: A self-image congruence analysis. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 4: 307-326.

- Runyan RC, Noh M, Mosier J (2013) What is cool? Operationalizing the construct in an apparel context. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 17(3): 322-340.

- Meyers LS, Gamst G, Guarino AJ (2006) Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.