Abstract

Targeted drug delivery is one of the most important branches of pharmaceutical science, and its importance for researchers lies in increasing drug efficacy and reducing drug toxicity through drug delivery carriers. Drug delivery system formulations can increase drug safety by reducing systemic side effects, preventing drug release into the stomach and damaging it, and preventing drug distribution to healthy tissues. They also prevent drug degradation, mask the bitter taste of the drug, and reduce costs. The aim of this study is to use the drug sulfasalazine to the colon in a drug delivery system based on azo hydrogels, which we cover with gellan polysaccharide, and to show its effect on the digestive system of the body and the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. To do this, first, distilled water was added to the sample beaker where we poured the gellan and mixed using a magnetic stirrer. Heating was performed for one hour to completely dissolve the gellan. Then, the ground drug was added while dissolving the gellan. Stirring continued for three hours and then the samples were emptied into a plastic container and placed in the refrigerator. 30 ml of deionized water was added to 10 ml of each sample, then they were titrated separately using a 10 M sodium hydroxide solution and a 10 M hydrochloric acid solution. The dialysis bag was cut into several pieces and then the bottom of the bag was closed with a piece of suitable thread that was completely cleaned and sterilized with PBS buffer and 20 ml of the samples were added to each bag. For each sample, 25 ml of isotonic PBS buffer with a pH = 0.7 was added to a 50 cc Falcon tube, and the dialysis bag and its contents were immersed in the Falcon tube. Then, the optical absorption or ultraviolet light was read using a spectrophotometer in both environments inside the dialysis bag and outside the bag during different hours. The cytotoxicity test is performed by several methods: NRU, CFU, MTT, XTT. In this study, we used the MTT test to investigate the toxicity of the substances on cell viability. We used the FTIR analysis test to identify unknown substances, determine the concentration and quality of the sample. This study, while confirming slow release, showed that the maximum drug release was within 48 hours in an environment similar to physiological conditions and with isotonic conditions. The successful development of nanoparticles for oral administration could change the treatment paradigm of many diseases and have a significant impact on future treatment outcomes.

Keywords:Drug release, inflammatory bowel disease, sulfasalazine, drug delivery, colon, gum gall

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a common digestive disease that causes inflammation and ulceration of the lining of the large intestine and small intestine. It can be painful, debilitating, and in some cases life-threatening. The inflammation can be limited to the intestinal wall or spread throughout the entire intestine, eventually leading to other serious illnesses in different parts of the digestive tract and anus. Sulfasalazine is one of the main and most effective drugs for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. It is an anti-inflammatory drug that contains two components: 5-aminosalicylic acid and sulfapyridine, which are linked by an AZO bond and are taken orally. Drug delivery is a method in which, by using medical methods and combining them with an engineering perspective, drugs or therapeutic molecules in general can be delivered to the desired target, i.e. the area under treatment, in a more effective way. Drug delivery to the colon is a new strategy that has received much attention. Selective release of drugs to the colon can not only control the required dose, but also reduce the systemic side effects caused by high doses. Peptide, protein, oligonucleotide drugs, and vaccines can be suitable candidates for this route. Drug release from the colonic route and through the absorption of cells in this route is another method of delivering drugs that are absorbed in small amounts from the previous parts of the digestive tract. However, there are some obstacles to choosing this route for drug delivery.

In this study, to deliver sulfasalazine to the colon, we coated it with gellan polysaccharide in a drug delivery system based on azo hydrogels.

Materials and method

The gellan sample was poured into the beaker and distilled water was added to it (Table1). Then, the beaker was covered and mixing was performed using a magnetic stirrer. Heating was continued at 90°C for one hour until the gellan was completely dissolved. It is also worth noting that 90°C is the temperature required to dissolve gellan gum.

After one hour, the ground drug was added to the gellan while dissolving it. Then, it was stirred for 3 hours using a magnetic stirrer. The prepared samples were emptied into plastic containers and stored in the refrigerator.

To 10 ml of each sample, 30 ml of deionized water were added, then titrated separately using 0.1 M hydrochloric acid and 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solutions. The numbers in Table 2 are in ml of acid or base used to reach the target PH. A pH meter was used to measure the final pH of the samples.

The dialysis bag was cut into 17 cm pieces. Then the bottom of the bag was closed with a piece of suitable thread thoroughly cleaned and sterilized with PBS buffer. 20 ml of the samples were added to each dialysis bag.

For each sample, 25 cc of isotonic PBS buffer with a pH of 0.7 was added to a 50 cc Falcon tube, and the dialysis bag and its contents were immersed in the Falcon tube.

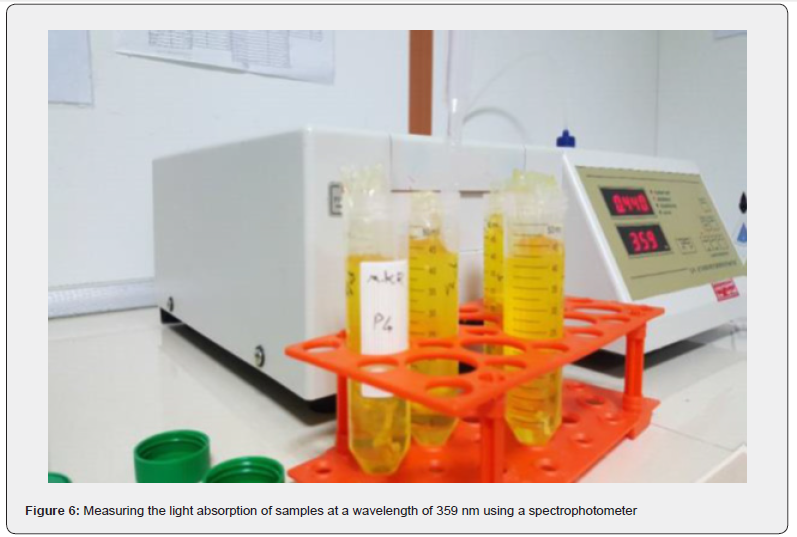

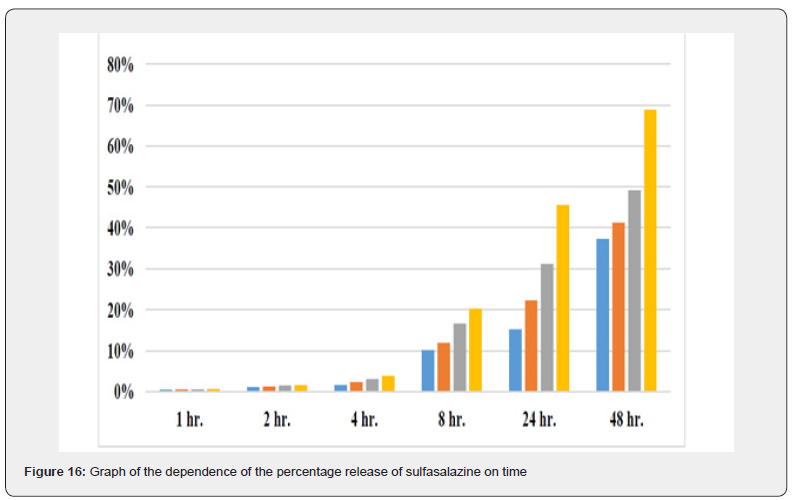

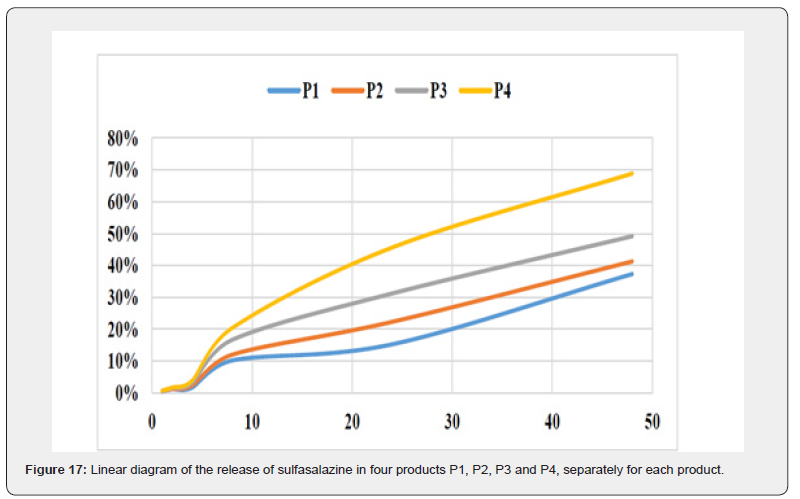

Then, the absorbance of O.D. (Absorbance) or UV light at a wavelength of 359 nm (λ 359 nm) was read using a spectrophotometer in both environments inside the dialysis bag and outside the bag at 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 and 48 hours.

Cytotoxicity test

Cell experiments were performed at the Institut Pasteur Center in the cell culture laboratory. Fibroblast cells were obtained from the Institut Pasteur and Iran cell bank and cultured in DMEM culture medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin antibiotics in a 1:1 ratio. Then, the grown cells were detached from the culture medium with trypsin and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Then, 200 microliters of cell suspension were cultured in 96-well BIOFIL microplates for 24 hours, with 5000 cells. Next, each sample was added to each well in the order shown in the table with mixed culture medium.

The microplates were placed in an incubator for 24, 48, and 72 hours at 37 degrees Celsius, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2 concentration. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, the effect of each sample on the aforementioned cell line was examined using the MTT colorimetric assay.

Cytotoxicity testing is performed according to ISO10993- 5 standard and is performed using three methods: NRU test, CFU test, MTT test and XTT test. The most common method in evaluating cytotoxicity is measuring cell viability using the MTT or -3 (4,5 - dimethylthiazol-2-yl -) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide method. After the incubation period, 37 microliters of MTT solution were added to each well and the microplates were kept in the incubator for another 3 hours. Finally, the resulting precipitate was dissolved using dimethyl sulfoxide, and the optical absorbance of the solution was read at a wavelength of 570 nm using an Elisa Reader.

Result and Discussion

FTIR Result:

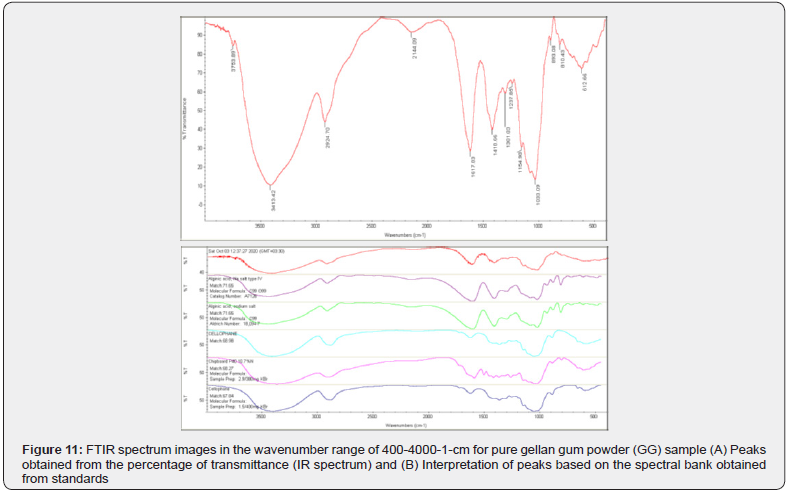

The images of FTIR spectra of six samples including gellan gum, sulfasalazine drug, hydrogel P1 to P4 are given. As you can see in the diagram related to sample GG, peaks at wavelengths of 3753/89, 3413/42, 2924/70, 2144/09, 1617/83, 1418/66, 1301/03, 1237/85, 1154/90, 893/08, 810/43 and 612/66 can be seen. According to the standard peak bank and the interpretation performed by the device software (Diagram 4 1 (B); compounds such as two types of sodium salt of alginic acid 4 and two types of cellophane have been detected

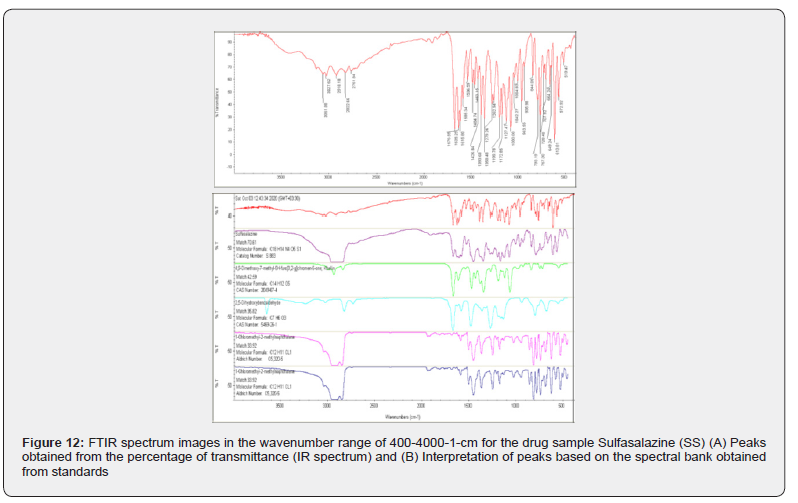

The diagram is for the SS sample, or the drug sulfasalazine with the closed formula (S5O4N14H18C). This drug, which is used in tablet form, in addition to the active ingredient; usually additives are added to it during the drug production process. Therefore, the desired tablet was made into powder form and after preparation, it was given to the device in crystalline form. According to diagram ,this drug has created numerous peaks due to its multiple functional groups, including: 88 / 3061, 62 / 3027, 1 / 2918, 66 / 2822, 84 / 2761, 55 / 1676, 25 / 1635, 80 / 1615, 34 / 1585, 59 / 1536, 74 / 1484, 15 / 1463, 68 / 1393, 48 / 1358, 26 / 1279, 94 / 1262, 78 / 1199, 85 / 1172, 47 / 1127, 00 / 1080, 27 / 1042, 55 / 963, 98 / 935, 19 / 793, 30 / 767, 40 / 728, 92 / 707, 24 / 664, 24 / 649, 81 / 613, 92 / 572 and 47 / 519.

According to the standard peak bank and the interpretation performed by the device software (Figure 4 2 (B);)) compounds such as sulfasalazine 1 with the molecular formula C18H14N4O5S1 and catalog number S883; molecule -4,9one; Khellin-5-g] chromen-furo[3,2-5H-methl-7-Dimethoxy with the molecular formula 5O12H14C and Cas Number: 2049-67-4 Figure(4,2); the next substance is the molecule 2,5-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde with the molecular formula 3O6H7C and Cas Number: 1-26-Cas Number: 5469 and finally -2-Chloromethyl-1hylnaphthalenemet with the molecular formula 1Cl11H12C and Cas Number: C5,320.

*LC- Least concern.

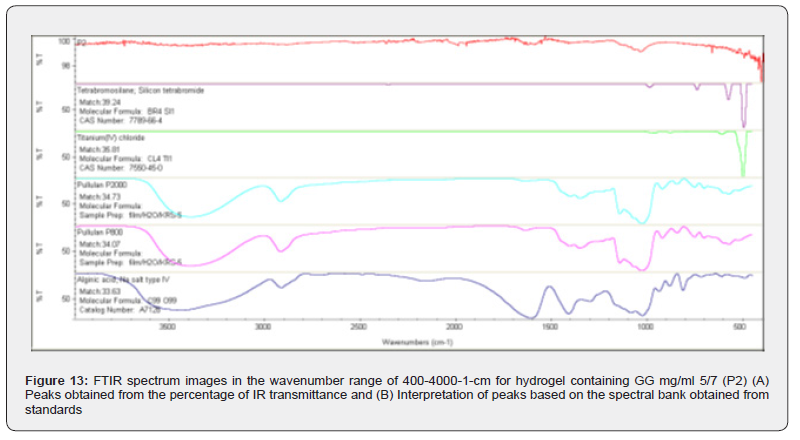

Figure 13 is the FTIR spectrum of the hydrogel product P2. The characteristic peaks observed in this material were at wavelengths of 3432/98, 43/1998, 1593/09, 1040/82, 698/96, 666/67, 636.85 and 497.49. In Figure (4 4) B), the compounds identified are as follows: silicon tetrabromide or tetrabromosilane with the formula 1Si4Br and 4-66-Cas Number: 7789; titanium IV chloride with the formula 1Ti4Cl and 0-45-Cas Number: 7550; pullulan P2000 and pullulan P800 were sodium salts of alginic acid. Figure (4 5) is also the FTIR spectrum of the hydrogel. P3. In Figure (A), the wavelengths 83 / 3727, 16 / 3626, 15 / 3379, 42 / 1628 and 38 / 1038 can be mentioned as indicators. Figure 4 5 (B) (During the interpretation made using the standard spectrum bank, similar compounds as before, namely alginic acid (sodium salt), Chipboard, L-Glucose and pullulan P2000, have been mentioned. Obviously, other compounds present in this hydrogel have been eliminated due to the restrictions imposed.

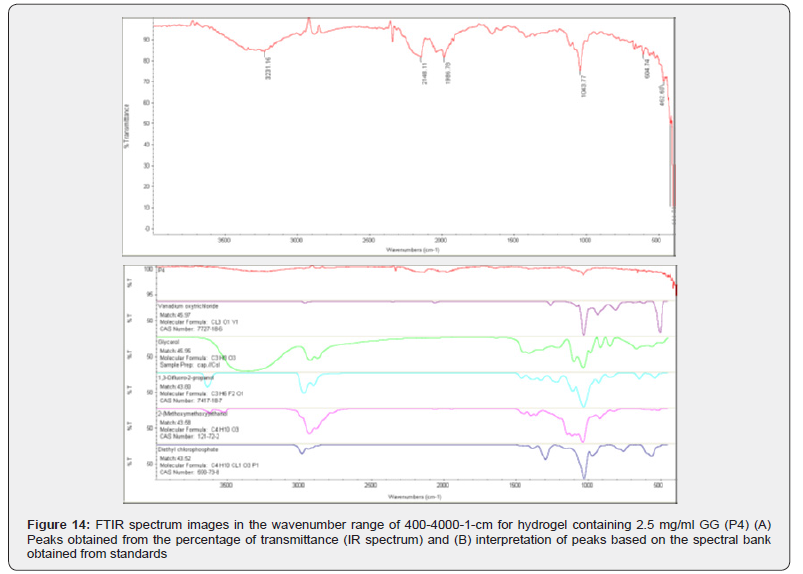

The graph also shows the infrared spectrum of hydrogel P4, which used the lowest amount of gellan gum in this series of experiments. The wavelengths with the most noticeable peaks were 16/3231, 11/2148, 78/1986, 77/1043, 74/604, and 60/462. In diagram (4 6) B) also compounds such as vanadium oxytrichloride with the formula 1V1O3Cl and 6-18-Cas Number: 7727; glycerol with the formula C3H9O3; propanol-2- Difluro-1,3 with the formula 1O2F6H3C and Cas Number: 7-18- 7417; (Methoxymethoxy)-2 Ethanol with the formula 3O10H4C and 2-72-Cas Number: 121 and diethyl chlorophosphate with the formula 1P3O1Cl10H4C and 8-73-Cas Number: 590 are mentioned.

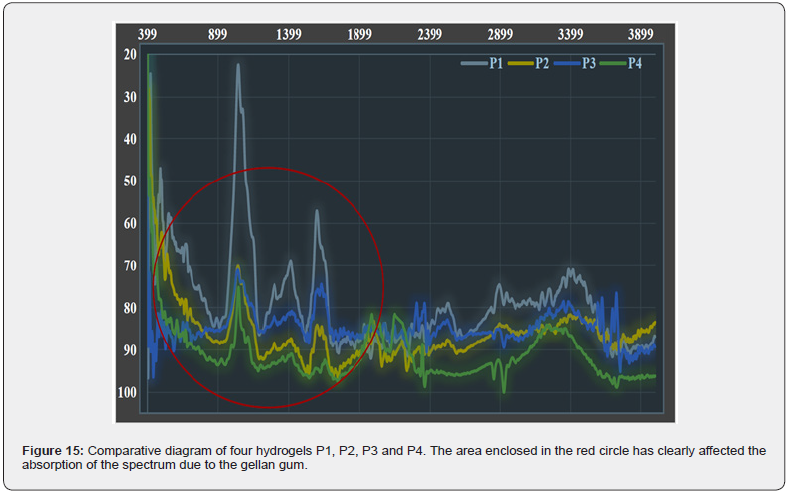

Figure 15 compares the four infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy spectra of the four produced hydrogels in reverse order of the Y axis. In the area enclosed by the red circle, it can be seen that the spectra are in complete agreement and only the amount of the transmitted spectrum in the wavenumber range of 500-2000 cm changes clearly. This difference in the transmitted spectrum is of course visible in all parts of the spectrum, but it is more pronounced in this range.

Resistance test PH

Solutions resist changes in pH according to the functional groups, the interaction of molecules together, and the ionization strength. Table (1) shows the amounts of 0.1 molar solution of each of the titrant solutions (hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide) used in milliliters. As you can see, the amount of solution required to change the pH is much greater with distance from the initial pH of each solution.

The four hydrogel products prepared differ only in the percentage of gellan gum. Since gellan is a molecule that gives the prepared material a gelling property; it is expected to play a role in drug release in physiological and chemical environments. The percentage of sulfasalazine released from the product to the outside of the semipermeable membrane was calculated. In order to simulate the conditions of the living environment, the dialysis bag was immersed in physiological serum solution and the absorption of electromagnetic waves at a wavelength of 359 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer at different times.

The graph shows the drug release rate in standard conditions and in the presence of a semipermeable barrier of a dialysis bag with a cut-off of 14 kDa over time in a linear manner. As you can see, with increasing time, the drug release ratio in product P1, which has the highest GG content, becomes further away from product P4, which has the lowest GG content, indicating the effectiveness of GG in releasing the drug more slowly. Also, in the first 4 hours of the study, all four products showed almost the same behavior, but in the eighth hour and after that, the difference between the different products became significant.

Conclusion:

Many new drugs are only available by injection. Alternative methods of injection, especially oral route, are highly desirable compared to the injectable route due to their convenience and patient compliance. Although oral route presents many challenges due to the presence of gastrointestinal barriers, polymeric nanoparticles can be used to overcome pH and enzyme barriers, but intestinal permeability barriers remain a significant challenge. So far, many methods have been used to overcome the intestinal epithelial barrier to effectively deliver biologics and nanodrugs. In vitro experiments to investigate salt release from hydrocolloids appear to be reliable, acceptable, and reproducible and can be compared with different gel structures and various other materials in the future. Mucoadhesives, using the intestinal mucus layer, prolong the residence time in the intestine and increase the concentration of drugs near the surface of epithelial cells. In addition, many mucus adhesives are permeabilizers, which open the tight junctions between epithelial cells so that drugs and pharmacological agents can cross this barrier. Other approaches have focused on targeting natural transcytic pathways, including M cells, the vitamin B12 pathway, and the FcRn pathway. Recent studies have shown that targeting transcytic pathways can efficiently deliver drugs and nanodrugs orally, but further investigation is needed before these technologies can be used clinically. Oral drug delivery systems are being developed for many different applications, such as oral drug delivery of chemotherapeutic agents for cancer treatment, local drug delivery to the intestine for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, and oral mucosal vaccination. Many proteins, especially insulin for the treatment of diabetes, have been loaded into nanoparticles for oral administration. The successful development of nanoparticles for oral administration could change the treatment paradigm of many diseases and have a significant impact on future therapeutic outcomes. This study, while confirming slow release, showed that the maximum drug release occurred within 48 hours in an environment similar to physiological conditions and with isotonic conditions.

References

- Vermonden T, Censi R, Hennink WE (2012) Hydrogels for protein delivery. Chem Rev 112(5): 2853-88.

- Goonoo N, Bhaw-Luximon A, Jhurry D (2014) Drug Loading and Release from Electrospun Biodegradable Nanofibers, J. Biomed. Nanotech 10(9): 2173-2199.

- Reddy PD, Swarnalatha D (2010) Recent Advances in Novel Drug Delivery Systems, Int. J.Pharm. Tech. Res 2: 2025-2027.

- Mainardes RM, Silva LP (2004) Drug Delivery Systems: Past,Present, and Future, Curr. Drug Targets 5(5): 449-455.

- Nikander K (1994) Drug Delivery Systems, J. Aerosol. Med 7: 19-24.

- Strebhardt K, Ullrich A (2008) Paul Ehrlich's magic bullet concept: 100 years of progress. Nature Reviews Cancer 8(6): 473-480.

- Torchilin VP (2000) Drug targeting. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 11: S81-S91.

- Lübbe AS, Alexiou C, Bergemann C (2001) Clinical applications of magnetic drug targeting. Journal of Surgical Research 95(2): 200-206.

- Rapoport N, Christensen D, Fain H, Barrows L, Gao Z (2004) Ultrasound-triggered drug targeting of tumors in vitro and in vivo. Ultrasonics 42(1): 943-950.

- Lin HM, Wang WK, Hsiung PA, Shyu SG (2010) Light-sensitive intelligent drug delivery systems of coumarin-modified mesoporous bioactive glass. Acta biomaterialia 6(8): 3256-3263.

- Meyer DE, Shin B, Kong G, Dewhirst M, Chilkoti A (2001) Drug targeting using thermally responsive polymers and local hyperthermia. Journal of controlled release 74(1): 213-224.

- Langer R (1998) Drug deliveryand targeting. Nature 392: 5-10.

- Widder KJ, Senyei AE, Scarpelli DG (1978) Magnetic microspheres: a model system for site specific drug delivery in vivo. Experimental Biology and Medicine 158(2): 141-146.

- Chong Li, Wang J, Wang Y (2019) Recent Progress in Drug Delivery, Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 9: 1145-1162.

- Klibanov AL(2006) Microbubble contrast agents: targeted ultrasound imaging and ultrasound-assisted drug-delivery applications. Investigative radiology 41(3): 354-362.

- Ngoepe M, Choonara YE (2013) Integration of Biosensors and Drug Delivery Technologies for Early Detection and Chronic Management of Illness, Journal Sensors 13(6): 7680-7780.

- Hirsjarvi S, Passirani C, Benoit JP (2011) Passive and active tumour targeting with nanocarriers. Current drug discovery technologies 8(3): 188-196.

- Gu FX, Karnik R, Wang AZ, Alexis F, Nissenbaum EL, et al. (2007) Targeted nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Nano today 2(3): 14-21.

- Ghasemzadeh H, Rashvand H (2014) Sodium Alginate/Talc-g-Poly Sodium Acrylate Nanocomposite for Delivery of Indomethacin, International Seminar on Polymer Science and Technology.

- Kudela P, Koller VJ, Lubitz (2010) Bacterial Ghost (BGs)-advanced Antigen and Drug Delivery System, Vaccine 28: 5760–5767.

- Omidi S, Pirhayati M, Kakanejadifard A (2020) Co-delivery of Doxorubicin and Curcumin by a pH Sensitive, Injectable, and in Situ Hydrogel Composed of Chitosan, Graphene and Cellulose Nanowhisker, Carbohydrate Polymers 231: 115745.

- Banihashem S, Nezhati MN, Panahia HA (2019) Synthesis of Chitosan-grafted-Poly (N vinylcaprolactam) Coated on the Thiolated Gold Nanoparticles Surface for Controlled Release of Cisplatin, Carbohydrate Polymers 227: 115333.

- Wichterle O, Lim D (1960) “Hydrophilic Gels in Biologic Use,” Nature 185: 117-118.

- Nagam SP, Jyothi AN, Poojitha J, Aruna S, Nadendla RR (2016) “A Comprehensive Review on Hy drogels,” Int. J. Curr. Pharm. Res 8: 19-23.

- Morkhande VK, Pentewar RS, Gapat SV, Sayyad SR, Amol BD, et al. (2016) “A Review on Hydrogel,” Indo Am. J. Pharm. Res 6: 4678-4689.

- Laftah WA, Hashim S, Ibrahim AN (2011) “Polymer Hydrogels: A Review,” Polym. Plas t. Technol. Eng 50: 1475-1486.

- Ullah F, Bisyrul M, Othman H, Javed F, Ahmad Z, Akil HM (2015) “Classification,Processing and Application of Hydrogels: A Review,” Mater. Sci. Eng., Part C 57: 414-433.

- Malekzade R, Varshosaz J, Merat S, Hadidchi S, Mirmajlesi SH, Vahedi H, et al. (2000) Crohn's, Disease: a review of 140 cases from Iran. Irn J Med Sci 25: 138-43.

- Ebrahimi Daryani N, Mohammadi HR, Ayermalou M (2001) Clinical and epidemiological characteristics in ulcerative colitis patients referred to Imam Hospital 1995-2000. Tehran University Medical Journal (TUMJ) 59(4): 80-5.

- Aghazadeh R, Zali MR, Bahari A, Amin K, Ghahghaie F, et al, (2005) Inflammatory bowel disease in Iran: A review of 457 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20(11): 1691-5.

- Masjedi Zadeh R, Hajiani E, Hashemi SJ, Azmi M, Shayesteh AK (2007) Epidemiological features of inflammatory bowel disease in Khozestan. Scientific Medical Journal 6: 54-63.

- Kornbluth A, Sachar DB (2004) Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol 99(7): 1371.

- Friedman S, Blumberg RS (2005) Inflammatory Bowel disease. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Longo DL, et al. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th edition. New York:McGrawhill 1776- 1789

- Sutherland L, Roth D, Beck Y, et al (2000) Oral 5- aminosalicylic acid for inducing remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD 000543.

- Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrnp DM (1987) Coated oral 5-ASA therapy for mildly to moderately acute ulcerative colitis. New Engl. J Med 317(26): 1625-1629.

- Linn FV, Peppercon MA (1992) Drug therapy for inflammatory bowel disease AM J Surg 164(1): 85-89.

- Meyer S (1988) The place of oral 5-ASA in the therapy of ulcerative colitis. AM J Gastroenterol 83(1): 64-66.

- Harish NM, Prabhu P, Charyulu RN, Gulzar MA, Subrahmanyam EV (2009) Formulation and Evaluation of in situ Gels Containing Clotrimazole for Oral Candidiasis. Indian J Pharm Sci 71(4): 421-427.

- Nairy HM, Charyulu NR, Shetty VA, Prabhakara P (2011) A pseudo randomised clinical trial of in situ gels of fluconazole for the treatment of oropharngeal candidiasis. Trials.

- Aggarwal SR (2014) What's fueling the biotech engine-2012 to 2013. Nature biotechnology 32(1): 32-9.

- Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, et al (2010) Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature 464(7291): 1067-70.

- Hrkach J, Von Hoff D, Ali MM, Andrianova E, Auer J, et al. (2012) Preclinical development and clinical translation of a PSMA-targeted docetaxel nanoparticle with a differentiated pharmacological profile. Science translational medicine 4(128): 128ra39-ra39.

- Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC (2012) Nanoparticle delivery of cancer drugs. Annual review of medicine 63: 185-98.

- Lanza GM, Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Hughes MS, Cyrus T, et al (2006) Nanomedicine opportunities for cardiovascular disease with perfluorocarbon nanoparticles 1(3): 321-9.

- Pridgen EM, Alexis F, Farokhzad OC (2015) Polymeric nanoparticle drug delivery technologies for oral delivery applications. Expert opinion on drug delivery 12(9): 1459-73.

- [46] Borner M, Schöffski P, De Wit R, Caponigro F, Comella G, Sulkes A, et al. Patient preference and pharmacokinetics of oral modulated UFT versus intravenous fluorouracil and leucovorin: a randomised crossover trial in advanced colorectal cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2002;38(3):349-58.

- [47] DiMeglio LA, Peacock M. Two‑year clinical trial of oral alendronate versus intravenous pamidronate in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2006;21(1):132-40.

- [48] Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, Warner E. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15(1):110-5.

- [49] Peppas NA, Kavimandan NJ. Nanoscale analysis of protein and peptide absorption: insulin absorption using complexation and pH-sensitive hydrogels as delivery vehicles. european journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2006;29(3-4):183-97.

- [50] Von Pawel J, Gatzemeier U, Pujol J-L, Moreau L, Bildat S, Ranson M, et al. Phase II comparator study of oral versus intravenous topotecan in patients with chemosensitive small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology. 2001;19(6):1743-9.

- [51] Pfeiffer P, Mortensen JP, Bjerregaard B, Eckhoff L, Schønnemann K, Sandberg E, et al. Patient preference for oral or intravenous chemotherapy: a randomised cross-over trial comparing capecitabine and Nordic fluorouracil/leucovorin in patients with colorectal cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(16):2738-43

- [52] Moulari B, Béduneau A, Pellequer Y, Lamprecht A. Lectin-decorated nanoparticles enhance binding to the inflamed tissue in experimental colitis. Journal of Controlled Release. 2014;188:9-17 .

- [53] Wilson DS, Dalmasso G, Wang L, Sitaraman SV, Merlin D, Murthy N. Orally delivered thioketal nanoparticles loaded with TNF-α–siRNA target inflammation and inhibit gene expression in the intestines. Nature materials. 2010;9(11):923-8 .

- [54] Gurunathan S, Han JW, Kim ES, Park JH, Kim J-H. Reduction of graphene oxide by resveratrol: A novel and simple biological method for the synthesis of an effective anticancer nanotherapeutic molecule. International journal of nanomedicine. 2015;10:2951.

- [55] Yang S, Liu Y, Jiang Z, Gu J, Zhang D. Thermal and mechanical performance of electrospun chitosan/poly (vinyl alcohol) nanofibers with graphene oxide. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials. 2018;1(4):722-30.

- [56] Oliveira JT, Martins L, Picciochi R, Malafaya P, Sousa R, Neves N, et al. Gellan gum: a new biomaterial for cartilage tissue engineering applications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials. 2010;93(3):852-63 .

- [56] Phillips GO, Williams PA. Handbook of hydrocolloids: Elsevier; 2009 .

- [57] Ghorbani M, Hamishehkar H, Tabibiazar M. BSA/chitosan polyelectrolyte complex: a platform for enhancing the loading and cancer cell-uptake of resveratrol. Macromolecular Research. 2018;26(9):808-13.

- [58] Kim KJ, Shin M-R, Kim SH, Kim SJ, Lee AR, Kwon OJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory and apoptosis improving effects of sulfasalazine and Cinnamomi cortex and Bupleuri radix mixture in TNBS-induced colitis mouse model. Journal of Applied Biological Chemistry. 2017;60(3):227-34 .