Abstract

This study compares the environmental and thermal performance of infrared (IR) shading elements for traditional roof constructions. Experiments on a historic barn assessed OSB panels, aluminum-laminated OSB, and polypropylene (PP) membranes. IR shading reduced heat gain by over 90%, with lightweight foil systems achieving the lowest thermal loads. A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) following ISO 14040 and DIN EN 15978 evaluated impacts across production, use, and disposal using the Environmental Footprint Method. PP membranes showed the best ecological profile, while aluminum-coated OSB, despite superior thermal performance at peak temperatures, had higher global warming potential. Considering cooling energy savings over 30 years, foil-based systems offer clear environmental benefits. These findings highlight the importance of combining thermal efficiency with sustainability in building envelope design.

Keywords:Infrared shading; Thermal radiation reduction; Historic building preservation; Life cycle analysis; Climate adaption strategies

Introduction

In the summers of 2021 and 2025, experiments were conducted on the physical mechanisms of infrared shading elements, which were discovered experimentally by Alfons Huber in 2021. The experiments were carried out in a historic agricultural storage building (barn) in Bad Goisern, featuring a warm roof construction. Individual rafter fields were equipped either with OSB board sheathing or with an underlay membrane. The aim was to reduce the thermal radiation emitted by the roof surface heated by direct solar exposure into the attic space [4]. The results demonstrated that the mechanism is highly effective, with the efficiency of such shading elements being greater when the rafter fields are ventilated, thereby improving the thermal discharge of the infrared shading elements.

The whole thermal load in August 2025 (analyzed for positive input only, without nightcooling potential) was 24.7 kWh/m² for the unshaded roof, 1.9 kWh/m² with an OSB panel, 1.6 kWh/m² for an OSB panel with aluminum sheathing and 1.5 kWh/m² for a foil cladded system.

The findings suggest that the low thermal mass of a foil (membrane) compared to the OSB panel, offers advantages, as the average surface temperature on the underside of the infrared shading elements facing the interior of the roof was lower. A test setup using aluminum-laminated OSB boards was evaluated, revealing that the low-emissivity surface significantly reduces thermal radiation, particularly at elevated temperatures.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the extent to which the ecological dimension can serve as a basis for decision-making in the selection of materials used for shading elements.

Method

Measurements

For this study, infrared shading elements as described in Kain et al. (2025) were used [1]. These consist of panels mounted between two rafters, as shown in figures are missing and attached figures in word document. One rafter field was cladded with a 12 mm OSB panel (part of it coated with a low-e aluminum foil), the next left unplanked serving as a reference and the third field was shielded with a standard underroof membrane. The rafter spacing is 88 cm, and the sheathing was installed over a length of 7.5 m. The rafter fields are open at the eaves to ensure efficient rear ventilation for the removal of accumulated thermal energy. At the ridge, the heat is discharged via cross-ventilation along the ridge axis.

The surface temperature of sheathing elements, the exterior air temperature and the interior air temperature were measured throughout August 2025. These temperature readings were used to estimate the thermal load of construction elements according to Equation 1, consisting of a convective and a radiative part following the method of Aguilar-Castro et al. [5].

q - energy transfer to the interior by convective and radiative

effects in W/m²

αi - interior convective heat transfer coefficient, estimated

with 5.0 W/m²K

Tr - surface temperature of the roof sheathing or IR shading

inside in K

Tamb temperature of the ambient interior air in K

σ - Stefan-Boltzmann constant 5.67*10^(-8) W/m²K4

ε - emissivity (dimensionless between 0 and 1)

Tc - surface temperature of construction elements in the attic

in K

Life Cycle Assessment

A standardized LCA was conducted in accordance with ÖNORM EN ISO 14040 [6]. The assessed system consists of the shading elements, including their installation on the existing wooden rafters. A service life of 30 years was assumed, followed by dismantling and disposal of the shading elements.

Goal of the LCA

The goal of the life cycle assessment is to compare three infrared shading solutions in order to derive ecologically advantageous designs for these constructions.

Functional Unit

The functional unit of this study is 1 m² of infrared shading element over a service life of 30 years. The system boundaries include material production, transport to the construction site, installation, the use phase, and end-of-life disposal. Emissions and energy credits beyond the life cycle (module D according to DIN EN 15978 [7]) were not considered in this study.

Impact Categories

For the impact assessment, the Environmental Footprint Method (EF 3.1) was applied. The following impact categories were evaluated: climate change, acidification, ecotoxicity, human toxicity, land use, ozone depletion, photochemical ozone creation potential, eutrophication potential, water pollution, and resource use.

Data Source and Modeling Software

For model development, data from Ökobaudat (2023 edition) were utilized. The modeling was carried out using the software OpenLCA (version 2.5).

Life Cycle Phases

Life cycle phases were considered according to Table 1 following DIN EN 15978 (2012).

Life Cycle Inventory

The life cycle inventory for the three shading variants was based on the authors’ experience during the installation of the experimental setups, which represent a 1:1 modeling of the actual building structure [2]. Table 2 presents the inventory for OSB cladding, Table 3 for foil cladding, and Table 4 for OSB with aluminum foil sheathing. Table 5 includes a potential plywood cladding which was not tested experimentally but considered theoretically to assess wood-based shading elements with low surface density.

Temperature of Interior Roof Surfaces

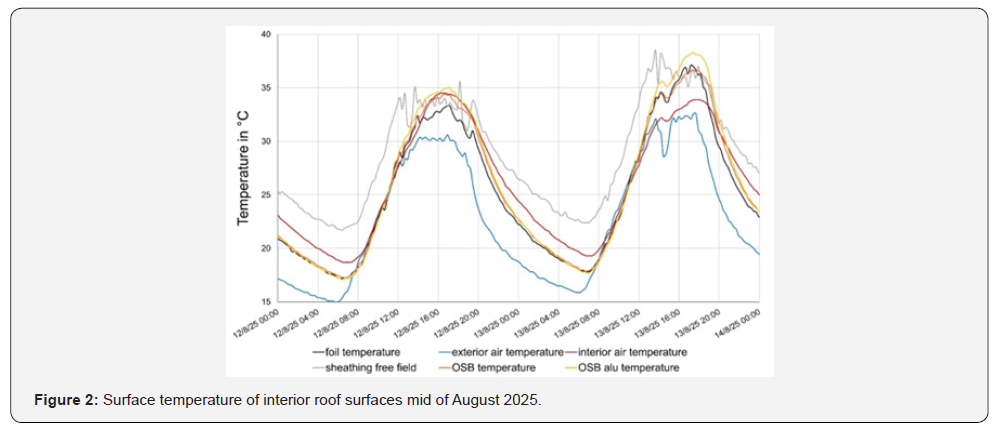

The interior roof surfaces of the experimental setup were analyzed for a representative hot day, August 13, 2025. On this day, the exterior air temperature increased from a minimum of 15.9 °C at 06:00 to a peak of 32.9 °C at 13:30. Subsequently, the temperature remained approximately stable, with minor fluctuations, until 17:45, after which it began a continuous decline.

The air temperature inside the barn closely mirrored the outdoor temperature due to its open structure and low thermal mass. It reached a minimum of 19.3 °C at 06:45 and then increased rapidly up to 32.2 °C at 14:14. Thereafter, the rise continued at a slower rate, reaching a peak of 33.9 °C at 17:45.

The interior surface temperature of the roof sheathing (without IR shading, grey line in Figure 2) closely follows the outdoor temperature, ranging from a minimum of 22.4 °C to a maximum of 38.5 °C. Throughout August 13, its temperature remains consistently higher than the surrounding air, likely due to thermal storage and radiative heat exchange from the attic construction elements.

The surface temperatures of the OSB panel and the underroof membrane exhibit similar values, largely consistent with the interior air temperature. At the peak temperature observed at 17:30, the membrane reaches slightly higher values than the OSB panel, attributable to its lower thermal mass, and subsequently cools more rapidly for the same reason.

The aluminum-coated OSB panel attains a maximum temperature 1.6 °C higher than its uncoated counterpart, most likely due to its reduced radiative efficiency. Interestingly, the temperature increase of the aluminum-coated panel begins at approximately 30 °C-a threshold at which radiative heat transfer surpasses convective heat exchange (see comparison with the cooler conditions on August 12).

Thermal Load of Interior Roof Surfaces

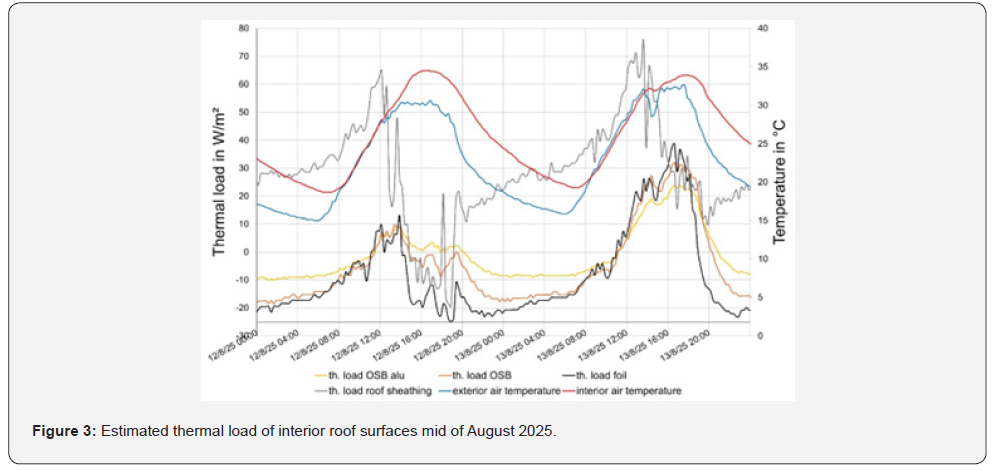

The thermal load of the construction elements was estimated using Equation 1 (Figure 3). Differences between the experimental setups become evident when radiative effects dominate. This is illustrated by the thermal load of the uncladded sheathing, which remains relatively constant over a 24-hour period on August 13, reaching a peak of 75 W/m² at 13:30. In contrast, the maximum thermal load of the shading elements occurs later, at 16:30, due to the cooling influence of the morning air within the ventilation layer.

The IR shading elements exhibit substantially lower thermal loads compared to the unshaded roof sheathing. Moreover, their thermal load becomes negative during nighttime and early morning hours. It should be noted that this behavior would differ in a closed and insulated space, where cooling is less efficient due to the reduced air exchange rate.

In absolute terms, the thermal load of the foil peaks at 16:30 with 39 W/m², followed by the OSB panel at 32 W/m² and the low-emissivity OSB panel at 23 W/m², making the latter the most favorable option during high-temperature periods. However, given that the foil cools significantly faster, it offers advantages in terms of the daily average thermal load.

Assuming that a positive thermal load of interior roof surfaces contributes to overheating in the rooms below, and disregarding negative loads, the cumulative thermal load for August was 1.81 kWh/m² for the OSB panel, 1.59 kWh/m2 for the aluminumcoated OSB panel, and 1.49 kWh/m² for the foil. In comparison, the uncladded, unvented roof sheathing would exhibit a thermal load of 24.7 kWh/m² under the same conditions.

These observations indicate that IR sheathing is highly effective in mitigating overheating. The monthly analysis highlights the advantages of lightweight foil or membrane sheathings, and it would be worthwhile to investigate a low-emissivity membrane system, as a surface with reduced emissivity proved beneficial for the OSB panel under elevated temperature conditions.

Result of the LCA

The results of the life cycle assessment clearly indicate that the shading variant using the underlay membrane shows the lowest contributions across all considered impact categories (excluding output parameters). The infrared shading solution with OSB sheathing is significantly more advantageous compared to the aluminum-coated OSB sheathing (Table 6). The potential plywood sheathing performs similarly to OSB panels in most categories but offers clear advantages in terms of global warming potential.

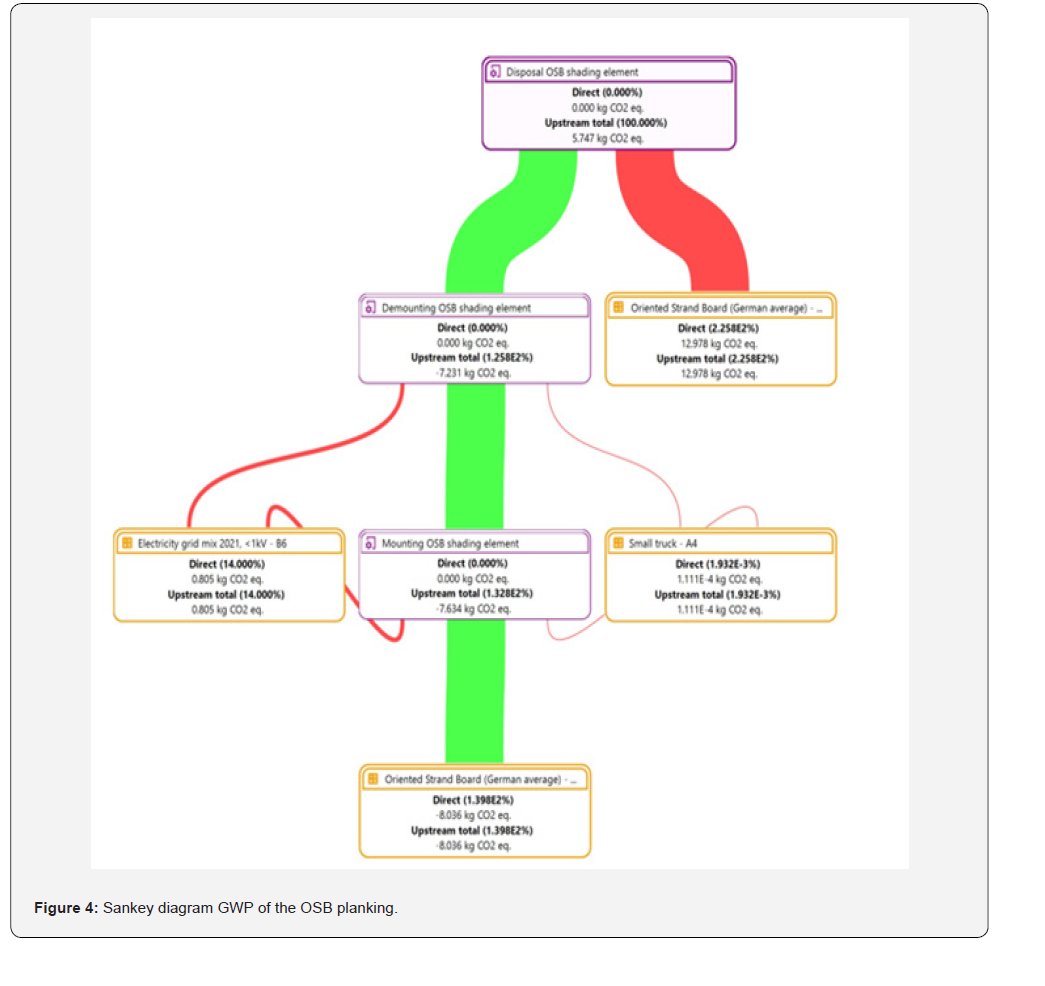

In the following, the contributions to global warming potential (GWP) are examined in detail. For the OSB sheathing element, the positive contributions dominate in the sense of a negative GWP of the OSB board. This ‘CO₂ credit’ is offset at the end of the life cycle during thermal recovery, as the CO₂ stored in the wood is reemitted. This process is typically associated with energy recovery; however, this lies outside the system boundaries of the present study (module D according to DIN EN 15978 [7]).

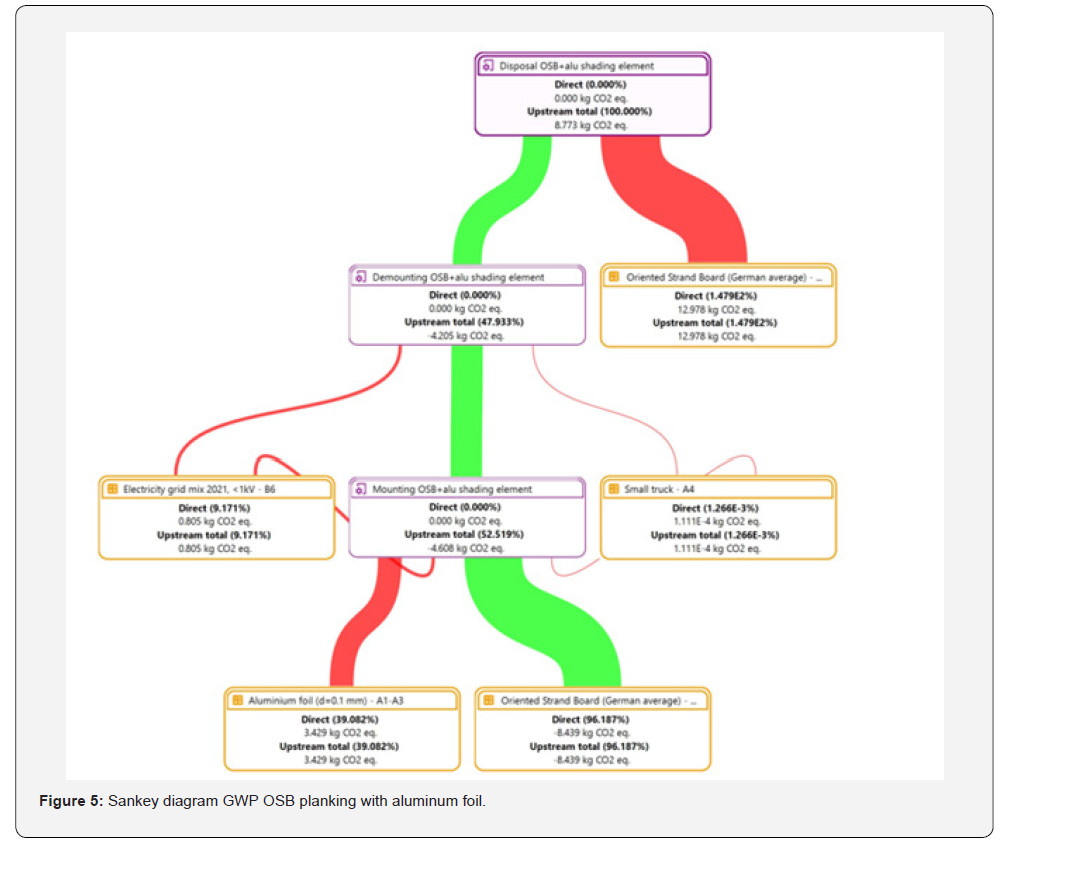

When the OSB sheathing is coated with an aluminum foil to reduce thermal radiation, the GWP for such a system is approximately 9 kg CO₂-equivalents, nearly twice as high as for the pure OSB variant. This is due to the comparatively high CO₂ input of the aluminum foil, amounting to almost 3.5 kg/m². In the end-of-life assessment, however, the aluminum foil is excluded, as recycling lies outside the system boundaries of the present study (Figure 5).

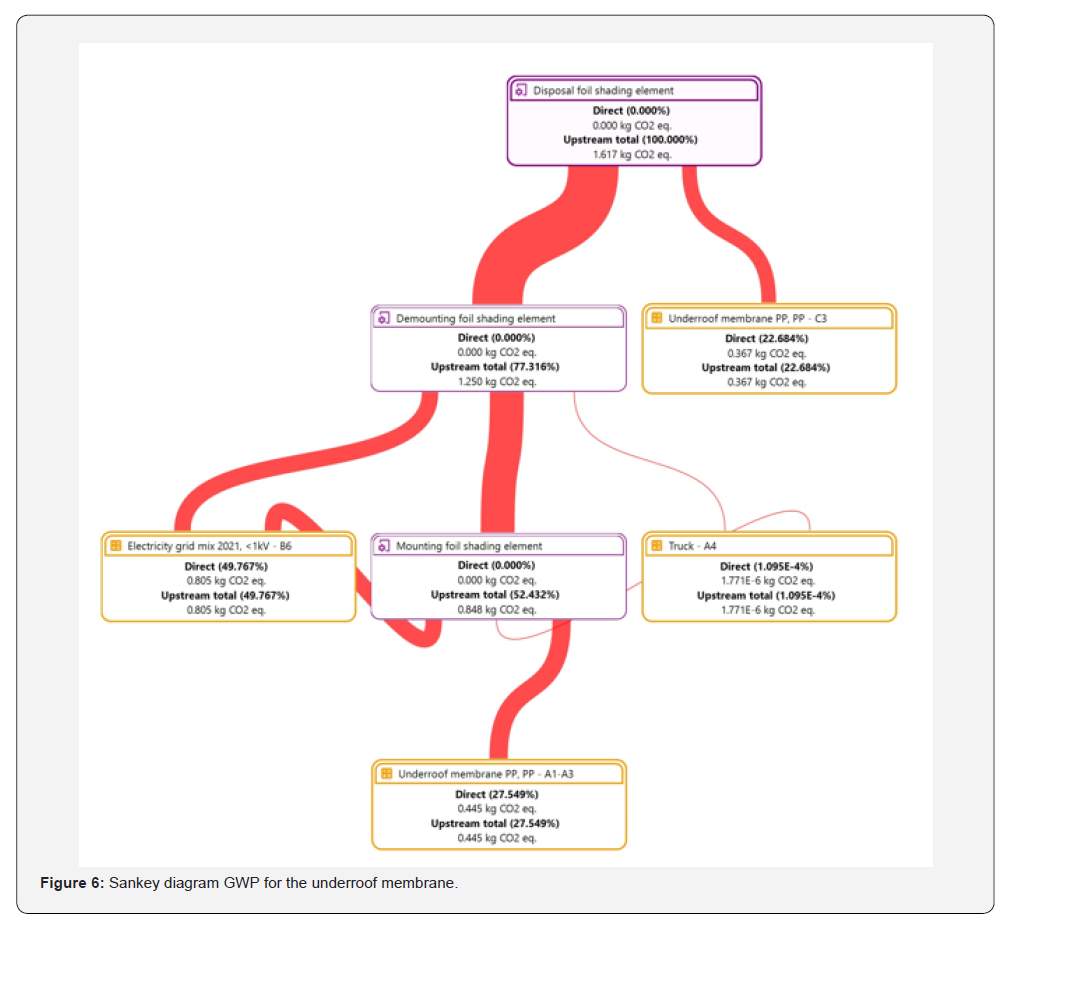

When using the PP underlay membrane as a shading element, its GWP is primarily determined by the PP foil itself and the electrical energy consumed during installation. However, the overall potential is very low, at approximately 1.6 kg CO₂- equivalents (Figure 6).

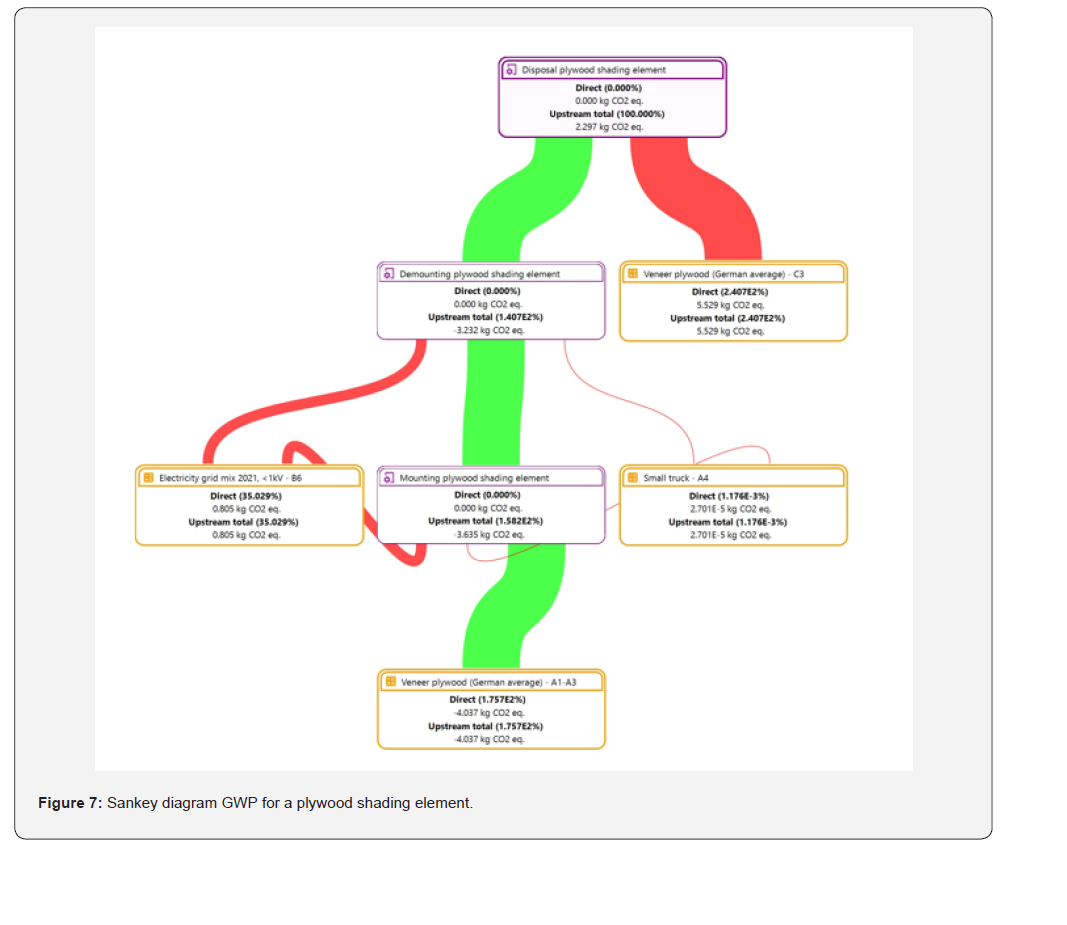

The potential plywood sheathing exhibits a similar GWP profile to OSB panels but has roughly half the CO₂ equivalents, primarily due to its significantly lower areal weight (Figure 7). Although it shows higher environmental impacts than foil cladding in most categories (Table 7), it may be the better choice for longer life cycles, as plastic foils tend to become brittle over time. While PP foils can be recycled or thermally disposed of, the practical risk remains uncontrolled disposal at the end of their life cycle (small plastic parts). This consideration favors lightweight wood-based systems, such as plywood, whose disposal and endof- life scenarios are far more predictable and reliable.

Infrared shading elements serve to reduce heat gain into the attic and the floors below. The thermal load is reduced by 93% - OSB) and 94% - foil and aluminum coated OSB, compared to an unshielded roof surface [1]. These measurements were obtained during August 2025.

By reducing heat gain through infrared shading elements, the demand for cooling energy in the attic and the floors below is significantly decreased. To approximate this energy savings, it is assumed that at the location of the test building (Salzkammergut, Upper Austria), cooling is only required during the months of June, July, and August.

As a first approximation, the heat energy input for June and July is assumed to correspond to the measured values obtained for August 2025, and is therefore estimated for the entire cooling period by multiplying by three. Measurement data from GeoSphere Austria indicate an average air temperature of 26.5 °C (June), 21.7 °C (July), and 24.6 °C (August) at 14:00 [8]. Assuming that 50% of the incident energy is transferred to the living spaces below, considering a service life of 30 years, and applying an average COP of 3.75 for typical split-type cooling units, the resulting electrical cooling energy demand is shown in Table 7.

In the life cycle perspective, the environmental impacts of the potentially avoided cooling energy are now compared to the environmental impacts of the shading system itself. This represents, in a sense, a normalization of environmental impacts and can also be understood as an amortization estimate of the environmental burdens caused by the installation of the infrared shading elements. For the electrical energy required for cooling, photovoltaic electricity generation was assumed, reflecting futureoriented technologies and the expected temporal coincidence of cooling demand with solar power availability.

In the case of foil cladding (Table 8), the environmental impacts of the estimated energy savings over the life cycle are, in all essential categories, a multiple (GWP factor 6, AP factor 21, PENRT factor 5) of the environmental impacts of the foil cladding over its life cycle, and thus a clear indication of its appropriateness.

The same comparison was carried out for OSB cladding with aluminum foil lamination, as this variant showed significantly lower heat radiation at peak temperatures in measurements compared to the other variants. This would make this design option technically interesting. However, when comparing the environmental impacts with those of the estimated energy savings, a more differentiated picture emerges (Table 9). In the majority of the impact categories compared, the environmental impact of the aluminum-coated OSB cladding is only slightly lower than that of the saved energy (GWP factor cooling energy referred to GWP OSB 1.1, AP factor 2.2., PENRT factor 0.7).

Although the estimation of future cooling energy requirements is subject to considerable uncertainty, the magnitude of the ratios in the comparisons carried out is nevertheless highly significant. Taking into account the LCA results and the thermal radiation measurements, IR shading using lightweight foil systems is in any case recommended, whereas OSB panels—and especially those with low-e coatings-although technically superior at higher temperatures, must be comprehensively discussed when considered in conjunction with LCA results. In future evaluations, uncertainties such as the development of local climate conditions at the respective building sites and the resulting cooling demand, the globally emerging differentiated assessment of the significance of the CO₂ footprint, and economic factors such as the price development of electricity will be of importance. In line with a neo-ecological approach, this study aims to take a first step toward a broad discussion of alternative building cooling systems that are both sustainable and cost-efficient.

Conclusions

The study revealed the following key findings:

a. IR shading reduces heat gain through the west-facing

roof surface by over 90% compared to an unshaded roof.

b. This effectiveness depends on a closed roof surface

combined with ventilation of the rafter fields.

c. While material selection has only a minor effect on

thermal load reduction, lightweight materials with low emissivity

(such as foils) achieve the best results by delivering the lowest

average thermal loads.

d. Life cycle analysis shows that among the systems

investigated, a PP underroof foil performs best and is preferred

from an environmental perspective.

e. For extended life cycles, wood-based claddings with low

areal weight become ecologically increasingly sensible.

Funding

This research was funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Housing, Arts, Culture, Media and Sports (BMWKMS) and by ICOMOS Austria.

References

- Kain G, Idam F, Kristak L (2025) Infrared (IR) Shading as a Strategy to Mitigate Overheating in Traditional Buildings. Buildings 15: 3471.

- Kain G, Idam F, Lubos K (2025) Performance optimized infrared (IR) shading elements for traditional buildings. Energies, under peer review.

- Idam F, Kain G (2025) Neo-ecological Approaches to Solving the Construction Crisis. CERJ 15: 1-4.

- Idam F, Kain G, Huber A (2025) Multifunctional Building Envelopes. CERJ 15.

- Aguilar-Castro KM, Cerino-Isidro JL, Torres-Aguilar CE, May Tzuc O, Macias-Melo EV, et al. (2024) Effect of interior and exterior roof coating on heat gain inside a house. Construction and Building Materials 454: 139045.

- ÖNORM EN ISO 14040. Environmental management - Life cycle assessment - Principles and framework; Austrian Standards: Vienna.

- DIN EN 15978 (2012) Sustainability of construction works - Assessment of environmental performance of buildings - Calculation method; German Institue for Standardization: Berlin.

- GeoSphere Austria (2025) Measuring Stations Monthly Data: Measuring Station Bad Goisern, Air Temperature 2 m Average Time II.