Circular Concrete: an Organisational Revolution?

Rem PC*

Faculty of Civil Engineering, Netherland

Submission: August 20, 2018;Published: September 05, 2018

*Corresponding Author: Rem PC, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Netherland; Tel: +31-0-15-27-83617; Email: P.C.Rem@tudelft.nl

How to cite this article: Rem PC. Circular Concrete: an Organisational Revolution?. Civil Eng Res J. 2018; 6(3): 555686. DOI:10.19080/CERJ.2018.06.555686

Opinion

Last summer, the European HISER conference surprised everybody with the announcement from one of Tongji University’s top institutes that high-rise towers had been built from recycle concrete in areas of China that are prone to earth quakes. At the same conference, Francois de Larrard, research director of Lafarge Holcim, informed the attendees that, from that moment onwards, the company offered recycle mortar as a standard product and that engineers who felt insufficiently prepared for the new material could refer to their new handbook for help. The surprise was understandable because the research that led to the breakthroughs highlighted at the conference had not been well published and the few scattered results that had reached the journals did not provide a complete picture. Before the conference, most engineers had believed that it was not economically feasible to produce high-grade new concrete from end-of-life (EOL) buildings. Therefore, research results from Delft University of Technology, showing that recycle mortar from advanced recycling processes is actually superior in its development of compressive strength and so recycle aggregate may save on cement, money and CO2, were difficult to swallow.

In the meantime, the political arena responded fast. The Dutch secretary of state Van Veldhoven predicted earlier this year that concrete will be circular in the Netherlands within 12 years and, this summer, the entire Dutch chain of companies involved in concrete agreed to a covenant stating that from now on concrete must be made with a steadily increasing volume percentage of recycle aggregate from EOL concrete, starting from 5%, and produce 30% less CO2 emission from 2030. The emission goal is particularly interesting because many coal power plants may shut down within this same period and so the supply of low-CO2 fly ash for cement may drop. There is also the possibility for a revolution in terms of organization.Political confidence suggests that the route to circular concrete is clear, but in reality, there are several options for organizing the transition and each option has its own key player.

The Chinese, for example, bet on a route starting with a fast, relatively uncontrolled demolition of buildings and then taking the waste as quickly as possible to a processing site outside the city. The main issue with uncontrolled demolition is that the EOL concrete gets mixed with a lot of other building materials. The result is a complex flow of waste while the only long-term acceptable quality of recycle aggregate allows less than 100ppm of light contaminants. It is not clear how this problem is going to be solved. Large-scale, economic recovery of clean EOL concrete from mixed waste flows is a technological hurdle that still needs to be taken. The alternative of selective demolition, for making clean EOL concrete flows, is economically possible in China, but it takes much more time before a site is ready for new construction activities: this is not considered an attractive option for China’s big cities.

In Europe, selective demolition is a routine procedure, and so relatively clean EOL concrete flows are widely available. Several advanced technologies are now close to market that turn the EOL concrete into a high-grade aggregate and a cement paste concentrate. The two critical steps in producing superior aggregate are to apply intensive attrition to the crushed concrete to remove fragile cement-rich parts and then effectively remove fines as well as light contaminants such as wood and foam from the flow. The coarse aggregate from such a process is suitable for replacing +2mm or +4mm gravel in new mortar (Figure 1). In general, it is found that, with the same amount of cement, recycle concrete has a larger early strength, but optimal performance and durability require a good consistency of the mortar (i.e., a well-tuned dosage of water and superplasticizer).

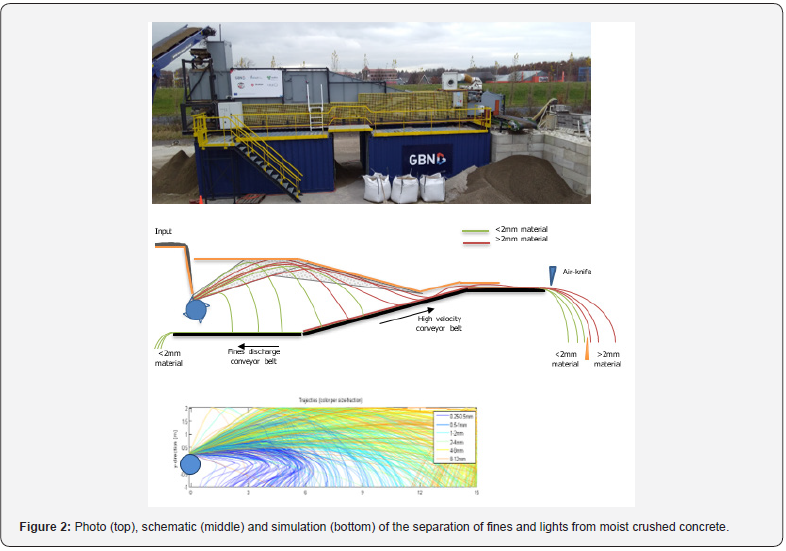

In one of the new technologies, the attrition step is extremely intensive so that much of the non-hydrated part of the old cement paste becomes liberated and reacts with the moisture in the EOL concrete to yield a dry product. This means that the fines can be eliminated relatively easily by screening or sifting. In another technology, attrition is less deep, and the fines and lights are extracted from the still moist concrete flow in a high-speed particle jet (Figure 2). In this latter technology, the separated fines and lights are post-processed in a heat-treatment up to 600 C, to eliminate the light contaminants and break the old cement paste from the sand in the absence of moisture (Figure 3). Mobile versions of the technology support about 150ton/h input to the crusher with a top size of 22mm.

One of the interesting questions is how circular concrete will be organized in Europe. In one extreme case, the new technologies can be operated near mortar suppliers or near prefab concrete industries. Selectively demolished concrete will then be transported out of town, processed and the aggregate is then immediately used for making new mortar or concrete at the same site. In this scenario, the production of concrete will remain with the same parties as today. In another extreme case, mobile versions of the recycling plant could run at the demolition site, while trucks carry the aggregate towards mobile mortar plants (and perhaps even 3D printers) at nearby construction sites in other parts of the town. The management and control of the concrete quality will then become the responsibility of the owner of the mobile mortar facility, and the quality of the recycled aggregate needs to be documented and guaranteed before shipment.

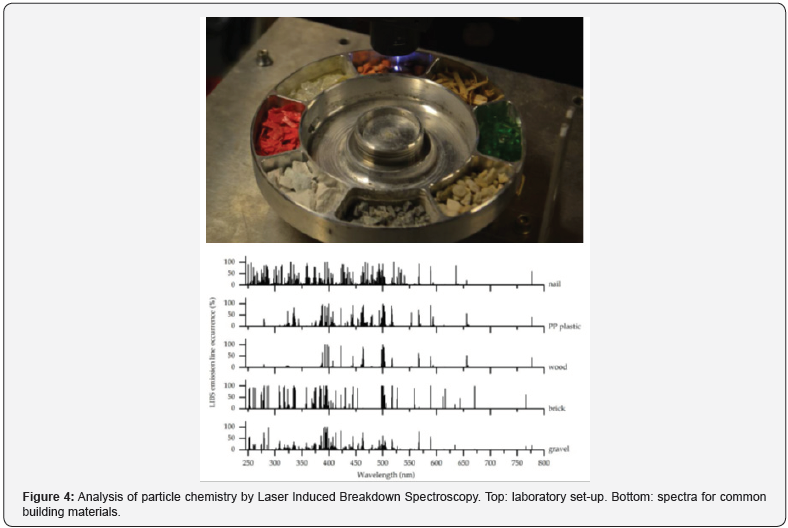

In all cases, it will be necessary for future recycling plants to convert a highly variable EOL concrete input (type of aggregate, type of cement, level of contamination) into an output that is within a very narrow range of quality. Since the input quality may fluctuate with every 100 tons fed to the plant, in principle so can the output. Manual sampling and laboratory analysis are therefore too slow and too expensive. One technology that can produce online statistics on particle surface chemistry as well as on grain size distribution is based on Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) (Figure 4). This technology scans the surface of the aggregate particles as they move along a conveyor belt. The laser strikes a plasma flame of less than a millimeter diameter up to 5,000 times for every ton of material, producing as many chemical analyses. In this way, the concentration of contaminants like wood, glass, brick, gypsum or metals can be measured and the type of cement of the parent concrete can be identified. Statistical data become available within minutes so that they can be inspected both by a potential client and by the operator of the plant. In case the surface of aggregates is not sufficiently clean, or the product contains too much fines or contaminants, the output can be rejected, and the recycling process adjusted before low-quality materials can end up in concrete.