Typhlitis (Neutropenic Enterocolitis): A Multidisciplinary Approach

Chinyere Pamugo1*, Angie Yohanna Gómez Malvacia2, Ileana Patricia McCall3, Yessika Erenia Artola Hernandez4, Ericka Nadeska Rodgers5, Maria Carlota Castillo Soto6, Andrea Nicole Abifaraj Daaboul7, Rebeca Beatriz Artola Hernandez8, Neha Vijay9 and Maria Isabel Gomez-Coral10

1UTHealth Science of Houston, USA

1Universidad Centroccidental Lisandro Alvarado, UCLA

1Universidad Evangélica de El Salvador

1Universidad de El Salvador

1Universidad Nacional Autónoma De Honduras

1Universidad del Zulia, Venezuela

1Universidad Católica de Honduras, Hondura

1Universidad de El Salvador

1University of Texas at El Paso, USA

1Universidad del Valle, México

Submission:March 21, 2025; Published:April 02, 2025

*Corresponding author:Chinyere Pamugo, UTHealth Science of Houston, USA

How to cite this article:Chinyere P, Angie Yohanna Gómez M, Ileana Patricia M, Yessika Erenia Artola H, Ericka Nadeska R, et al. Typhlitis (Neutropenic Enterocolitis): A Multidisciplinary Approach. Paper Recycling Ann Rev Resear. 2025; 12(5): 555846.DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2025.12.555846

Abstract

Typhlitis, or neutropenic enterocolitis, is a life-threatening gastrointestinal complication that predominantly affects immunocompromised patients, particularly those undergoing intensive chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. The pathophysiology of typhlitis is characterized by mucosal injury, bacterial translocation, and systemic inflammatory response, often resulting in sepsis and multi-organ failure if not promptly managed. Early diagnosis relies on clinical suspicion supported by imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) to identify hallmark features including bowel wall thickening and pneumatosis intestinalis. Management primarily involves aggressive supportive care, including bowel rest, fluid resuscitation, and broad-spectrum antibiotics targeting gram-negative bacilli, gram-positive cocci, and anaerobes. Surgical intervention is reserved for patients with complications such as bowel perforation, necrosis, or uncontrolled hemorrhage, with right hemicolectomy and ileostomy being the preferred procedures in severe cases. Despite advances in antimicrobial therapy and critical care, the prognosis remains guarded, particularly in patients with profound and prolonged neutropenia. Long-term management focuses on recurrence prevention through prophylactic antibiotics, gut microbiome modulation, and personalized oncologic treatment strategies to minimize further mucosal injury. Emerging research on microbiome-targeted therapies holds promise for reducing gastrointestinal complications in neutropenic patients. A multidisciplinary approach is essential for optimizing outcomes and improving survival in affected individuals.

Keywords:Typhlitis; Neutropenic enterocolitis; Chemotherapy; Immunosuppression; Bacterial translocation; Surgical management; Gut microbiome; Multidisciplinary approach

Keywords:ALL: Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia; ANC: Absolute Neutrophil Count; CT: Computed Tomography; FMT: Fecal Microbiota Transplantation; GS: General Surgery; NPO: Nothing by Mouth; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; PTE: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

--->

Introduction

Typhlitis, also known as neutropenic enterocolitis, is a life-threatening inflammatory and infectious process that primarily affects the cecum and proximal colon in immunocompromised patients. It is most commonly observed in individuals with profound neutropenia, particularly those undergoing intensive chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. The condition is characterized by transmural inflammation, often complicated by bacterial translocation, ischemia, and, in severe cases, perforation, leading to significant morbidity and mortality [1]. The relevance of typhlitis is particularly pronounced in oncology, hematology, and post-transplant settings, where aggressive immunosuppressive therapies predispose patients to gastrointestinal complications [2]. It is frequently reported in patients with acute leukemia, lymphoma, and those receiving bone marrow transplantation, as these populations experience prolonged and severe neutropenia. The increasing use of high-dose chemotherapy and novel immunotherapies has also increased awareness of this condition in recent years [2]. Epidemiologically, typhlitis has been reported in approximately 5-10% of patients receiving intensive chemotherapy, with the highest incidence observed in those with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants [3]. The mortality rate varies widely, ranging from 20% to 50%, depending on the severity at presentation and the presence of complications such as perforation, sepsis, or multiorgan failure. Rapid recognition and intervention are critical, as delays in diagnosis or inadequate management can lead to catastrophic outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach is essential to optimize treatment and improve survival rates. Given the highrisk nature and potential fatality of typhlitis, a comprehensive understanding of its pathophysiology, early diagnostic markers, and evidence-based treatment strategies is imperative for improving patient outcomes [4]. This review explores the current insights into the diagnosis, management, and prevention of typhlitis, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary collaboration in high-risk populations.

Pathophysiology

Typhlitis is a potentially life-threatening condition that primarily affects people with lowered immune systems and individuals undergoing cancer chemotherapy [1-6]. The condition is characterized by inflammation of the cecum and potentially other parts of the intestinal tract, resulting from a complex interplay involving neutropenia, mucosal injury, and bacterial translocation.

Role of Neutropenia in Susceptibility to Bacterial Translocation

Neutropenia is marked by a drastic reduction in the number of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell vital for the body’s innate immune response [6]. This condition significantly distorts the immune defense mechanism, increasing infection susceptibility [6]. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT), which harbors a diverse band of commensal and pathogenic bacteria, becomes a potential source of systemic infection [6,7]. In a healthy immune system, neutrophils contain and regulate the gut microbiota effectively. However, during neutropenia, this containment is disrupted, facilitating the translocation of bacteria across the intestinal mucosa into the bloodstream with evidence of low neutrophil counts < 500 cell/microliter, elevated C-reactive (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) [6-9]. The gut microbiota is not just localized; it interacts with various body systems, including the skin, oral cavity, lungs, vagina, and even the brain [6-8]. It effectively enhances the production of key immune components such as immunoglobulin A (IgA), antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), and several innate and adaptive immune cells, which are essential for maintaining gut health and overall immunity [6, pg2].

Mucosal Injury Due to Chemotherapy and Gut Microbiota Alterations

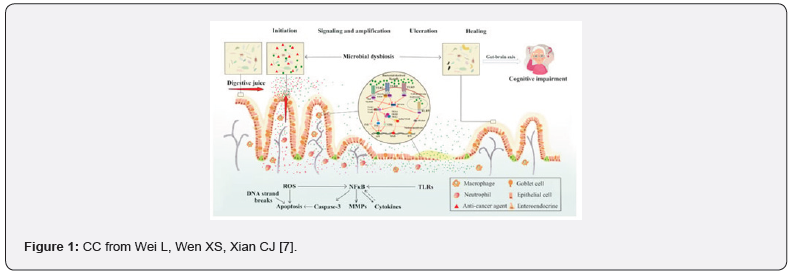

Chemotherapy often induces mucositis, which damages the intestinal epithelium and contributes to diminished secretion of digestive fluids [7,8]. This damage leads to a decreased population of good gut microbiota, compromising the gut’s barrier function and increasing the actions of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines [7]. Wei, Wen, & Xian expanded that “Specific toll-like receptors (TLRs) located on immune cells identify the cell wall components of bacteria, including peptidoglycan, which is recognized by TLR-2, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) detected by TLR-4, flagellin by TLR-5, and unmethylated DNA (CpG DNA) through TLR-9” [7]. The injury caused by mucositis is progressive by dysbiosis, which occurs due to an imbalance in gut microbiota, negatively enhancing chronic inflammation and weakening mucosal integrity [7,8]. The altered composition of microbiota, combined with a diminished ability for epithelial regeneration, creates a permissive environment for bacterial invasion [7,8]. This invasion not only “disrupts immunological homeostasis but can also have profound impacts on mental health, linking gut and brain function through the brain-gut axis” [6-8] (Figure 1).

Bacterial Invasion and Ischemic Damage

Bacterial translocation [BT] triggers an inflammatory process that can lead to ischemic damage within the intestinal wall [7]. This ischemic process, on the other hand, arises due to impaired blood flow, exacerbating tissue necrosis and disrupting the gut’s morphological structure and function [7-8,10]. In the bloodstream, BT can trigger sepsis-a life-threatening systemic inflammatory cascade that can further compromise organ function [8,10]. Also, the proliferation exacerbations caused by bacterial invasion lead to intestinal perforation, where holes are formed in the intestinal wall, significantly increasing the risk of life-threatening complications, such as peritonitis and organ failure/s [10,11]. The mortality risk associated with typhlitis is substantial, underscoring the importance of early recognition, aggressive management, and preventive strategies in immunocompromised patients [11].

Clinical manifestations

The most common symptoms seen in neutropenic enterocolitis (NE) include fever and abdominal pain (often RLQ, but can be diffuse), in addition to nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, peritonitis, and abdominal distention [12,13]. Bowel wall thickening on imaging can help narrow the differential [14]. Though not as common, patients may also exhibit a palpable boggy cecum, melena, or hematochezia [13,15]. Abdominal compartment syndrome has also been reported in the setting of ascites [16]. Without symptomatic resolution and early diagnosis, progressive decline in the form of life-threatening complications, including sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), intraabdominal abscesses, pneumatosis intestinalis, bowel necrosis, perforation, hemorrhage, and multi-organ failure, can occur [12,17]. At-risk immunocompromised populations include those undergoing organ transplantation, those receiving chemotherapy treatment for hematological malignancies or solid tumors, and immunosuppressive conditions such as AIDS [18]. For those receiving chemotherapy, symptoms can occur anywhere between ten days to two weeks after treatment [13,15].

Diagnostic Approach

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings in typhlitis are crucial for diagnosing and managing the condition, often revealing signs of infection and inflammation. A key feature is neutropenia, typically observed in patients with chemotherapy or hematologic malignancies, where neutrophil counts are significantly low, sometimes below 500 cells/μL. Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are common, indicating systemic inflammation. In some cases, pancytopenia is seen, where reductions occur across all blood cell types, including red blood cells and platelets, especially in patients with severe bone marrow suppression. Additionally, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels may rise due to tissue damage, and electrolyte imbalances such as hyponatremia and hypokalemia may occur due to gastrointestinal losses [19-23]. Procalcitonin (PCT) levels have been extensively studied as a biomarker for bacterial infections and sepsis, particularly in the context of febrile neutropenia and other severe infections. However, the specific relationship between PCT levels and typhlitis (neutropenic enterocolitis) remains less welldocumented in the literature [24]. While there is no direct evidence linking procalcitonin levels specifically to typhlitis, the elevated PCT levels observed in severe bacterial infections and sepsis suggest that it could serve as a valuable marker in the diagnosis and management of typhlitis in neutropenic patients [24]. The presence of these lab findings, combined with clinical symptoms like abdominal pain and fever and imaging showing bowel wall thickening, aids in diagnosing typhlitis. CRP levels, in particular, can be valuable for monitoring the severity of inflammation. The severity and duration of neutropenia directly correlate with the symptoms and outcomes of typhlitis, as neutrophil recovery is essential for resolution [21-24]. Differentiating typhlitis from other conditions is important, and stool studies are essential to rule out infections like Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile). Key tests for C. difficile include Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAAT), Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) Antigen Test, and Toxin A and B Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA). Additionally, routine stool cultures and NAATs are necessary for detecting other enteric pathogens such as Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter [25]. Blood cultures are also vital in diagnosing and treating typhlitis, as neutropenic patients are at a high risk of bacteremia. Blood cultures should be collected before initiating antibiotics to ensure accurate pathogen identification, allowing for more targeted antimicrobial therapy, improving patient outcomes, and reducing complications [25].

Imaging Modalities

Imaging studies play a crucial role in diagnosing and managing typhlitis, with several modalities available depending on clinical circumstances and institutional capabilities. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast is the gold standard for diagnosing typhlitis [12,17,26]. CT imaging typically reveals characteristic findings such as circumferential bowel wall thickening of the cecum and ascending colon, often exceeding 5 mm. The thickening may be asymmetric and can involve other colon or small intestine segments in more severe cases [26]. CT can also identify pneumatosis intestinalis, which appears as gas within the bowel wall, indicating advanced disease with mucosal disruption. In cases where perforation has occurred, CT can detect pneumoperitoneum (free air in the peritoneal cavity), an ominous sign that typically necessitates urgent surgical intervention. Additional findings may include pericecal fat stranding, cecal distention, and pericolonic fluid collections or abscesses, all of which help assess the disease’s extent and severity [26,27].

While CT remains the primary imaging tool, ultrasonography provides a valuable alternative, particularly in pediatric populations, pregnant patients, or settings where CT may not be readily available. Ultrasound findings in typhlitis include cecal wall thickening (typically appearing as a hypoechoic rim surrounding the cecum), decreased peristalsis, and increased echogenicity of pericecal fat. The non-invasive nature and absence of radiation exposure make ultrasound an attractive option for initial evaluation and follow-up studies. However, its accuracy is operator-dependent and may be limited by patient factors such as obesity or excessive bowel gas [27,28]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represents another alternative imaging modality that may be considered in select cases. MRI offers excellent soft tissue contrast without radiation exposure, making it suitable for patients who require repeated imaging studies. With high sensitivity, it can detect bowel wall thickening, mucosal enhancement, and pericolonic inflammation. However, the longer acquisition times, higher cost, and limited availability compared to CT or ultrasound restrict its routine use in the acute setting. Nevertheless, MRI may be particularly valuable in patients with renal insufficiency who cannot receive iodinated contrast agents for CT studies [27-31]. The choice of imaging modality should be tailored to the individual patient’s clinical situation, considering factors such as disease severity, comorbidities, and local resources. Regardless of the modality, prompt imaging is essential for early diagnosis and appropriate management of typhlitis.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common symptoms of Neutropenic enterocolitis (NE) are abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fever [32]. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension are also common symptoms. Abdominal pain can be localized in the lower right quadrant or can be more diffuse. Tenderness on palpation can be found at the RLQ [33]. Typhlitis frequently mimics appendicitis on presentation, and the main difference is that appendicitis has leukocytosis and Typhlitis has neutropenia [34,35]. When comparing NE with Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile), colitis is a cause of diarrhea in hospitalized patients and using antibiotics like cephalosporins, Clyndamycin, and penicillin, among others. C. Difficile is one of the most common causes of nosocomial infections. C. difficile infection is usually suspected when hospitalized patients develop diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever, but patients can develop dehydration, loss of appetite, and nausea as well [36].

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a member of the herpesvirus family and forms latent infection after the resolution of the primary infection. After the primary CMV infection, CMV remains in host cells, and CMV replication is controlled by the immune system in immunocompetent patients [37]. Immunodeficiency is the leading risk factor for invasive CMV diseases. Invasive CMV mostly affects the gastrointestinal tract in immunocompromised patients. Clinical manifestation of CMV colitis in immunocompromised patients varies and depends on the site of involvement, which could cause odynophagia, abdominal pain, hematochezia, and fever [38,39]. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which comprises Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic, systemic, autoimmune disease. Both may present with abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, or muscle spasms in the region of the pelvis and weight loss [40]. Ischemic colitis (IC), characterized by insufficient blood supply and oxygen delivery to the colon, is the most common form of bowel ischemia [41]. The severity of IC depends on the degree of parietal involvement, ranging from superficial mucosa inflammation to full-thickness transmural necrosis, a life-threatening condition that requires surgery [42]. Because of the overlapping symptoms of NE with many abdominal pathologies, this is an entity that should be considered in any differential for a patient with febrile RLQ pain, not just those with obvious immunosuppression.

Management Strategies: Internal Medicine and Surgery Perspectives

Supportive Care

The cornerstone of managing typhlitis begins with aggressive supportive care measures implemented immediately upon diagnosis. Bowel rest is essential to minimize intestinal peristalsis and reduce the risk of perforation in the compromised bowel wall. This typically involves establishing nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status until clinical improvement is observed. In patients presenting significant abdominal distention or radiographic evidence of ileus, nasogastric tube placement for intestinal decompression becomes necessary to relieve pressure on the affected bowel segments and reduce the risk of aspiration [43]. Fluid resuscitation represents another critical component of supportive care, as many patients present with significant volume depletion due to decreased oral intake, diarrhea, and third-spacing into the bowel wall and peritoneal cavity. Careful attention to fluid balance with isotonic crystalloid solutions helps maintain adequate tissue perfusion while preventing fluid overload. Concurrent with volume resuscitation, vigilant monitoring and correction of electrolyte abnormalities, particularly hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia which may result from gastrointestinal losses, is essential for preventing cardiac arrhythmias and optimizing intestinal function [44]. Pain management warrants special consideration in patients with typhlitis. Opioid analgesics are generally preferred for their efficacy and relatively favorable safety profile in this context. Importantly, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be strictly avoided due to their association with increased risk of gastrointestinal mucosal damage and bleeding, which could exacerbate the already compromised intestinal mucosa in neutropenic patients. Additionally, NSAIDs may mask fever, an important clinical indicator of treatment response or disease progression. The administration of opioids should be balanced against their potential to exacerbate ileus, with careful titration and adjunctive measures such as stool softeners employed when necessary [45].

Antibiotic Therapy

Prompt initiation of empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is imperative in managing typhlitis given its potentially rapid progression and the immunocompromised state of affected patients. The selection of antimicrobial agents should provide comprehensive coverage against gram-negative bacilli (including Pseudomonas aeruginosa), gram-positive cocci, and anaerobic organisms, which commonly constitute the polymicrobial intestinal flora that may translocate across the damaged intestinal barrier [46]. Monotherapy options with excellent broad-spectrum coverage include piperacillintazobactam, meropenem, or imipenem-cilastatin. These betalactam antibiotics with beta-lactamase inhibitors or carbapenems provide robust activity against the typical pathogens encountered in typhlitis and are often preferred as first-line agents due to their excellent tissue penetration and proven efficacy in neutropenic infections. Alternatively, combination therapy with cefepime plus metronidazole offers comparable coverage, with cefepime targeting gram-negative and gram-positive aerobes while metronidazole provides dedicated anaerobic coverage [47]. For patients with prolonged neutropenia (typically exceeding 7-10 days), persistent fever despite appropriate antibacterial therapy, or those receiving intensive chemotherapy regimens associated with severe mucosal damage, consideration should be given to adding antifungal coverage. Candida species, particularly Candida albicans, may contribute to the pathogenesis of typhlitis in these high-risk individuals. Echinocandins (e.g., caspofungin) or lipid formulations of amphotericin B are typically recommended in this scenario due to their broad antifungal spectrum and favorable safety profile [48]. Antibiotic therapy should be continued until neutrophil recovery (absolute neutrophil count >500 cells/μL) and resolution of clinical symptoms, including defervescence, abdominal pain improvement, and normalization of gastrointestinal function. This typically requires a minimum of 10-14 days of treatment, though the duration may be extended based on clinical response and the presence of complications [49- 50].

Surgical Considerations (GS focus)

Typhlitis, also known as neutropenic enterocolitis, can be challenging to diagnose and to treat for most physicians, since there is a high mortality seen in these patients, and there are controversial opinions on its form of treatment. Initially, established management of the disease is recommended to follow a thorough electrolyte follow-up, bowel rest with nasogastric suction, total parenteral infusion, and blood transfusions depending on the patient’s hemodynamic status. Surgical intervention is only given in extreme cases, such as the patient presenting with signs and/or symptoms of necrosis, perforation, and persistent bleeding.The mortality rate has been reported to range from 50% to 100% in patients that have not been treated and require surgical intervention. Physicians don’t typically select abdominal surgery as their first choice to treat this disease because of exhaustive complications in patients with neutropenia [51-53]. Patients who happen to experience severe systemic symptoms, such as sepsis, or as well with those who evidently have signs of perforation, obstruction, massive bleeding, or abscess formation, require surgery effective immediately. All the necrotic tissue must be removed, typically through right hemicolectomy, ileostomy, and mucous fistula. In patients who carry a less severe case, a divided ileostomy may also be implemented. If this necrotic area is not excised, particularly in patients who are severely immunocompromised, it can be fatal. With prompt identification, typhlitis and its underlying causes risk of complications can be minimized with early preventive measures in a timely manner [52- 55]. The most common diagnosis prompting surgical consultation in neutropenic patients is neutropenic enterocolitis, followed by small bowel obstruction, Clostridium difficile infection, diverticulitis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pseudo-obstruction, splenic rupture, and an unclear diagnosis. Neutropenic enterocolitis is a common complication of cytotoxic chemotherapy, and most of the patients with this specific pathology must be further evaluated for possible malignancies. There are certain diseases linked that predispose to have neutropenic enterocolitis, such as ALL (acute lymphocytic leukemia), being ranked as the highest risk. Patients mostly get treated with a right hemicolectomy, and although there have been reports of successful recovery, still surgery is not the first approach to treatment [53-56].

Although most patients get treated successfully with conservative management, those who had clinical signs of bowel perforation and/or peritonitis were submitted to surgery. Some of the other indications to surgery were the inability to diagnose bowel perforation, other pathologies such as appendicitis, and patients who were hemodynamically unstable (mostly due to life threatening hemorrhage). Most studies suggest a right hemicolectomy with a defunctioning ileostomy indication in the area where necrosis of the colon has occurred, in comparison to primary anastomosis which had a higher rate of complications in neutropenic patients. Another procedure that could be implemented in pancolonic disease is defunctioning ileostomy, but carries a heavier risk of prolonged postoperative sepsis in patients with poor neutrophil counts [54-59]. Clinical signs such as abdominal pain and fever in patients with typhlitis can serve as very important health indicators for physicians to suspect this pathology. Diagnosing this disease as early as possible and giving the right treatment can be lifesaving and enhance the prognosis. However, supportive care still remains the primary form of treatment and surgery must be needed to survive in minimal cases [59].

Prognosis and Long-Term Management

Typhlitis, or neutropenic enterocolitis, is a severe and potentially life-threatening complication observed in immunocompromised patients, particularly those undergoing chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. The prognosis of typhlitis is influenced by several key factors, including the severity of neutropenia, the timeliness of intervention, and the patient’s response to therapy. Severe neutropenia, particularly an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of less than 500 cells/μL, is associated with an increased risk of bacterial translocation, sepsis, and mortality (Gorschlüter et al., 2005). Early recognition and aggressive management with broad-spectrum antibiotics, bowel rest, and supportive care are essential to improving outcomes. Delayed intervention has been correlated with increased morbidity and higher rates of surgical intervention due to complications such as bowel perforation or necrosis (Rodríguez-Villar et al., 2021). The response to initial therapy, including clinical improvement and resolution of neutropenia, plays a crucial role in determining patient outcomes. Poor response or persistent symptoms despite appropriate treatment is indicative of a worse prognosis and often necessitates escalation of care [60].

The risk of recurrence of typhlitis is a major concern, particularly in patients undergoing multiple cycles of chemotherapy. Recurrent episodes have been reported in patients with continued myelosuppression and mucosal injury due to repeated cytotoxic exposure. The incidence of recurrence can be as high as 20-30% in high-risk populations, necessitating tailored preventive strategies (Rodríguez-Villar et al., 2021). Prophylactic antibiotics, particularly fluoroquinolones, have been explored as a potential preventive measure in patients with prolonged neutropenia or a history of typhlitis. While some studies suggest that prophylaxis reduces the incidence of febrile neutropenia and bacterial infections, concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance and microbiome dysbiosis warrant cautious use (Freifeld et al., 2011). Future research is needed to determine optimal patient selection criteria for prophylactic antibiotic therapy [61].

The gut microbiome has emerged as a crucial factor in the pathophysiology and prevention of typhlitis. Chemotherapyinduced mucosal injury, coupled with the broad-spectrum antibiotic use often required in neutropenic patients, can lead to significant alterations in gut microbiota composition. This dysbiosis has been linked to an increased risk of gastrointestinal infections and inflammation, contributing to the development of enterocolitis (Taur et al., 2014). Strategies to modulate the gut microbiome, including probiotic supplementation, prebiotic use, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), are being investigated as potential interventions to restore intestinal homeostasis. Preliminary data suggest that preserving a diverse and healthy microbiota may reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal complications in neutropenic patients, but large-scale clinical trials are needed to confirm these findings and establish standardized protocols for microbiome-targeted therapies [62]. In conclusion, the prognosis of typhlitis is dependent on early recognition, timely intervention, and the severity of neutropenia. Recurrent episodes are a significant concern, particularly in patients undergoing multiple chemotherapy cycles, highlighting the need for effective preventive strategies. While prophylactic antibiotics may be beneficial in select high-risk patients, concerns about antimicrobial resistance must be carefully considered. Emerging evidence on gut microbiome modulation presents a promising avenue for reducing typhlitis risk, though further research is required to integrate these strategies into clinical practice. A multidisciplinary approach involving oncologists, infectious disease specialists, and gastroenterologists is essential for optimizing long-term management and improving patient outcomes [63].

Conclusion

Typhlitis remains a critical and potentially fatal complication in immunocompromised patients, particularly those undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Despite advances in supportive care and antimicrobial therapy, the condition continues to pose significant management challenges due to its rapid progression, high morbidity, and risk of recurrence. Early recognition through clinical suspicion and imaging is paramount in initiating timely interventions and reducing mortality. While most cases can be managed conservatively with bowel rest, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and fluid resuscitation, a subset of patients with severe complications such as bowel perforation, necrosis, or persistent sepsis requires surgical intervention. Right hemicolectomy with ileostomy remains the procedure of choice in such cases, though surgery is associated with increased perioperative risks in neutropenic individuals. Long-term management strategies emphasize recurrence prevention, including judicious use of prophylactic antibiotics and emerging microbiome-targeted therapies aimed at preserving intestinal integrity. Future research should focus on refining risk stratification models, optimizing prophylactic strategies, and exploring innovative microbiomemodulating interventions. Given the complexity of typhlitis, a multidisciplinary approach is crucial in improving patient outcomes and survival rates.

References

- Marcus Gorschlüter, Ulrich Mey, John Strehl, Carsten Ziske, Michael Schepke, et al. (2005) Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults: systematic analysis of evidence quality. Eur J Haematol 75(1): 1-13.

- Rodrigues FG, Dasilva G, Wexner SD (2010) Neutropenic Enterocolitis. World J Gastroenterol 23(1): 42-47.

- Davila ML (2007) Neutropenic enterocolitis as a complication of chemotherapy in acute leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2(2): 95-98.

- Gorschlüter M, Mey U, Strehl J (2002) Neutropenic enterocolitis in cancer patients: a 10-year prospective study. Clin Infect Dis 35(8): 1044-1050.

- Ioannis Alexandros Charitos, Salvatore Scacco, Antonella Cotoia, Francesca Castellaneta, Giorgio Castellana, et al. (2025) Intestinal microbiota dysbiosis role and bacterial translocation as a factor for septic risk. Int J Mol Sci 26(5): 2028.

- Zhang D, Frenette PS (2019) Cross-talk between neutrophils and the microbiota. Blood 133(20): 2168-2177.

- Wei L, Wen XS, Xian CJ (2021) Chemotherapy-induced intestinal microbiota dysbiosis impairs mucosal homeostasis by modulating toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Int J Mol Sci 22(17): 9474.

- Bo-Young Hong, Takanori Sobue, Linda Choquette, Amanda K Dupuy, Angela Thompson, et al. (2019) Chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis is associated with detrimental bacterial dysbiosis. Microbiome 7(1): 66.

- Penack, P Rempf, M Eisenblätter, A Stroux, J Wagner, E et al. (2007) Bloodstream infections in neutropenic patients: early detection of pathogens and directed antimicrobial therapy due to surveillance blood cultures. Ann Oncol 18: 1870-1874.

- Acibadem Health Point Blog. Ischemic colitis and sepsis risk explained. Acibadem Health Group.

- Minasyan H (2019) Sepsis: mechanisms of bacterial injury to the patient. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 27(1): 19.

- Samane Nematolahi, Ali Amanati, Hossein Molavi Vardanjani, Mohammadreza Pourali, Mahnaz Hosseini Bensenjan, et al. (2025) Investigating neutropenic enterocolitis: a systematic review of case reports and clinical insights. BMC Gastroenterol 25(1): 17.

- Urbach DR, Rotstein OD (1999) Typhlitis. Can J Surg 42(6): 415-419.

- Xia R, Zhang X (2019) Neutropenic enterocolitis: a clinico-pathological review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 10(3): 36-41.

- Rodrigues FG, Dasilva G, Wexner SD (2017) Neutropenic enterocolitis. World J Gastroenterol 23(1): 42-47.

- Vliet M, Hoeven HJ, Velden WJ (2013) Abdominal compartment syndrome in neutropenic enterocolitis. Br J Haematol 160(3): 273.

- Giuseppe Bertozzi, Aniello Maiese, Giovanna Passaro, Alberto Tosoni, Antonio Mirijello, et al. (2021) Neutropenic enterocolitis and sepsis: towards the definition of a pathologic profile. Medicina (Kaunas) 57(6): 638.

- Edoardo Benedetti, Benedetto Bruno, Francesca Martini, Riccardo Morganti, Emilia Bramanti, et al. (2021) Early diagnosis of neutropenic enterocolitis by bedside ultrasound in hematological malignancies: a prospective study. J Clin Med 10(18): 4277.

- Hadar Moran, Isaac Yaniv, Shai Ashkenazi, Michael Schwartz, Salvador Fisher, et al. (2009) Risk factors for typhlitis in pediatric patients with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 31(9): 630-634.

- Federico Coccolini, Mario Improta, Massimo Sartelli, Kemal Rasa, Robert Sawyer, et al. (2021) Acute abdomen in the immunocompromised patient: WSES, SIS-E, WSIS, AAST, and GAIS guidelines. World J Emerg Surg 16(1): 40.

- Vitaliy Poylin, Alexander T Hawkins, Anuradha R Bhama, Marylise Boutros, Amy L Lightner, et al. (2021) The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Clostridioides difficile Infection. Dis Colon Rectum 64(6): 650-668.

- J Michael Miller, Matthew J Binnicker, Sheldon Campbell, Karen C Carroll, Kimberle C Chapin, et al. (2018) A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2018 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis 67(6): e1-e94.

- EJ Giamarellos-Bourboulis, P Grecka, G Poulakou, K Anargyrou, N Katsilambros, et al. (2001) Assessment of procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker of underlying infection in patients with febrile neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis 32(12): 1718-1725.

- Reith HB, Mittelkötter U, Wagner R, Thiede A (2000) Procalcitonin (PCT) in patients with abdominal sepsis. Intensive Care Med 26(2): S165-169.

- JA Katz, ML Wagner, MV Gresik, DH Mahoney, DJ Fernbach (1990) Typhlitis: an 18-year experience and postmortem review. Cancer 65(4): 1041-1047.

- JA Katz, ML Wagner, MV Gresik, DH Mahoney, DJ Fernbach (1990) Typhlitis. An 18-year experience and postmortem review. Cancer 65(4): 1041-1047.

- Kirkpatrick ID, Greenberg HM (2003) Gastrointestinal complications in the neutropenic patient: characterization and differentiation with abdominal CT. Radiology 226(3): 668-674.

- Davila ML (2006) Neutropenic Enterocolitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 22(1): 44-47.

- Marcus Gorschlüter, Ulrich Mey, John Strehl, Carsten Ziske, Michael Schepke, et al. (2005) Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults: systematic analysis of evidence quality. Eur J Haematol 75(1): 1-13.

- C Cartoni, F Dragoni, A Micozzi, E Pescarmona, S Mecarocci, et al. (2001) Neutropenic enterocolitis in patients with acute leukemia: prognostic significance of bowel wall thickening detected by ultrasonography. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3): 756-761.

- Gomez L, Martino R, Rolston KV (1998) Neutropenic enterocolitis: spectrum of the disease and comparison of definite and possible cases. Clin Infect Dis 27(4): 695-699.

- Shafey A, Ethier MC, Traubici J, Naqvi A, Sung L (2013) Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of enteritis, typhlitis, and colitis in children with acute leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 35(7): 514-517.

- Hsu TF, Huang HH, Yen DH, Kao WF, Chen JD, et al. (2004) ED presentation of neutropenic enterocolitis in adult patients with acute leukemia. Am J Emerg Med 22(4): 276-279.

- DJ Humes, J Simpson (2006) Acute appendicitis. Humes DJ, Simpson J. BMJ 333(7567): 530-534.

- Mohannad A Abu-Hilal, Jason M Jones (2018) Typhlitis; is it just in immunocompromised patients? Abu-Hilal MA, Jones JM. Med Sci Monit 14(8): CS67-70.

- Cassini A, Plachouras D, Eckmanns T, Abu Sin M, Blank HP, et al. (2016) Burden of Six Healthcare-Associated Infections on European Population Health: Estimating Incidence-Based Disability-Adjusted Life Years through a Population Prevalence-Based Modelling Study. PLoS Med 13(10): e1002150.

- Picarda G, Benedict CA (2018) Cytomegalovirus: Shape-Shifting the Immune System. J Immunol 200(12): 3881-3889.

- Fakhreddine AY, Frenette CT, Konijeti GG (2019) A Practical Review of Cytomegalovirus in Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2019: 6156581.

- Wetwittayakhlang P, Rujeerapaiboon N, Wetwittayakhlung P, Sripongpun P, Pruphetkaew N, et al. (2021) Clinical Features, Endoscopic Findings, and Predictive Factors for Mortality in Tissue-Invasive Gastrointestinal Cytomegalovirus Disease between Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised Patients. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2021: 8886525.

- Gerhard Rogler, Abha Singh, Arthur Kavanaugh, David T Rubin (2021) Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Concepts, Treatment, and Implications for Disease Management. Gastroenterology 16(4): 1118-1132.

- Montoro MA, Brandt LJ, Santolaria S, Gomollon F, Puértolas BS, et al. (2011) Clinical patterns and outcomes of ischaemic colitis: results of the Working Group for the Study of Ischaemic Colitis in Spain (CIE study) Scand J Gastroenterol 46(2): 236-246.

- Fitzgerald JF, Hernandez LO (2015) Ischemic colitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 28(2): 93-98.

- Marcus Gorschlüter, Ulrich Mey, John Strehl, Carsten Ziske, Michael Schepke, et al. (2005) Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults: systematic analysis of evidence quality. Eur J Haematol 75(1): 1-13.

- Portugal R, Nucci M (2017) Typhlitis (neutropenic enterocolitis) in patients with acute leukemia: a review. Expert Rev Hematol 10(2): 169-174.

- Rodrigues FG, Dasilva G, Wexner SD (2017) Neutropenic enterocolitis. World J Gastroenterol 23(1): 42-47.

- Cloutier RL (2010) Neutropenic enterocolitis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 24(3): 577-584.

- Alison G Freifeld, Eric J Bow, Kent A Sepkowitz, Michael J Boeckh, James I Ito, et al. (2011) Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 52(4): e56-e93.

- Nesher L, Rolston KV (2013) Neutropenic enterocolitis, a growing concern in the era of widespread use of aggressive chemotherapy. Clin Infect Dis 56(5): 711-717.

- Brian D Badgwell, Janice N Cormier, Curtis J Wray, Gautam Borthakur, Wei Qiao, et al. (2008) Challenges in surgical management of abdominal pain in the neutropenic cancer patient. Ann Surg 248(1): 104-109.

- Colombe Saillard, Lara Zafrani, Michael Darmon, Magali Bisbal, Laurent Chow-Chine, et al. (2018) The prognostic impact of abdominal surgery in cancer patients with neutropenic enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis, on behalf the Groupe de Recherche en Réanimation Respiratoire du patient d'Onco-Hématologie (GRRR-OH). Ann Intensive Care 8(1): 47.

- Ertürk UŞ, Ermiş Turak E, Kaynar L, Fadel E (2020) Current Approach to Neutropenic Enterocolitis. Erciyes Med J 42(2): 119-120.

- Rodrigues FG, Dasilva G, Wexner SD (2017) Neutropenic enterocolitis. World J Gastroenterol 23(1): 42-47.

- Xia R, Zhang X (2019) Neutropenic enterocolitis: A clinico-pathological review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 10(3): 36-41.

- Moir CR, Scudamore CH, Benny WB (1986) Typhlitis: selective surgical management. Am J Surg 151(5): 563-566.

- Jolissaint JS, Harary M, Saadat LV, Madenci AL, Dieffenbach BV, et al. (2019) Timing and Outcomes of Abdominal Surgery in Neutropenic Patients. J Gastrointest Surg 23(4): 643-650.

- Aksoy DY, Tanriover MD, Uzun O, Zarakolu P, Ercis S, et al. (2007) Diarrhea in neutropenic patients: a prospective cohort study with emphasis on neutropenic enterocolitis. Ann Oncol 18(1): 183-189.

- Alt B, Glass NR, Sollinger H (1985) Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults. Review of the literature and assessment of surgical intervention. Am J Surg 149(3): 405-408.

- Colombe Saillard, Lara Zafrani, Michael Darmon, Magali Bisbal, Laurent Chow-Chine, et al. (2018) The prognostic impact of abdominal surgery in cancer patients with neutropenic enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis, on behalf the Groupe de Recherche en Réanimation Respiratoire du patient d’Onco-Hématologie (GRRR-OH). Ann Intensive Care 8(1): 47.

- RC Shamberger, J Weinstein, MJ Delorey, RH Levey (1986) The medical and surgical management of typhlitis in children with acute nonlymphocytic (myelogenous) leukemia. Cancer 57(3): 603-609.

- Alison G Freifeld, Eric J Bow, Kent A Sepkowitz, Michael J Boeckh, James I Ito, et al. (2011) Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update. Clinical Infectious Diseases 52(4): e56-e93.

- Marcus Gorschlüter, Ulrich Mey, John Strehl, Carsten Ziske, Michael Schepke, et al. (2005) Neutropenic enterocolitis in adults: systematic analysis of evidence quality. Eur J Haematol 75(1): 1-13.

- Rodríguez-Villar S, Muñoz-Cobo P, Pérez-Lago L, et al. (2021) Neutropenic enterocolitis: a review from pathogenesis to treatment Frontiers in Oncology 11: 667944.

- Ying Taur, Joao B Xavier, Lauren Lipuma, Carles Ubeda, Jenna Goldberg, et al. (2014) Intestinal domination and the risk of bacteremia in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases 55(7): 905-914.