Nature of Space

Patrice Dassonville F*

Author of The Invention of Time and Space: Origins, Definitions, Nature, Properties, France

Submission: July 05, 2024; Published: July 15, 2024

*Corresponding author: Patrice Dassonville F, Author of The Invention of Time and Space: Origins, Definitions, Nature, Properties, France

How to cite this article: Patrice Dassonville F, Author of The Invention of Time and Space: Origins, Definitions, Nature, Properties, France Ann Rev Resear. 2024; 11(3): 555815. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2024.11.555815

Abstract

The physical space has no materiality. It leads to theoretical consequences that can no longer be ignored.

Keywords: Big Bang; Materiality; Multi-disciplinarity; Origin of space; Metaphorical units

Introduction

The physical space is not what people usually think. Thus, we are not indebted to physics for the discovery of the nature of space. Scientific circles do not dare to define it, and dictionary definitions are just sophistry. In fact, these are archaeology and linguistics which gave us the privilege to observe the emergence of spatiality in some major cultural movements. Thanks to archaeology we see space being born in various forms such as the cosmology of Sumerians scholars, the map of Nippur, or the architectural feats in Egypt. The evolution of everyday language in Latin literature allows us to define space and clarify its nature. Among theoretical consequences, the outbreak of the Big Bang does not correspond to the birth of space.

Origin of Space

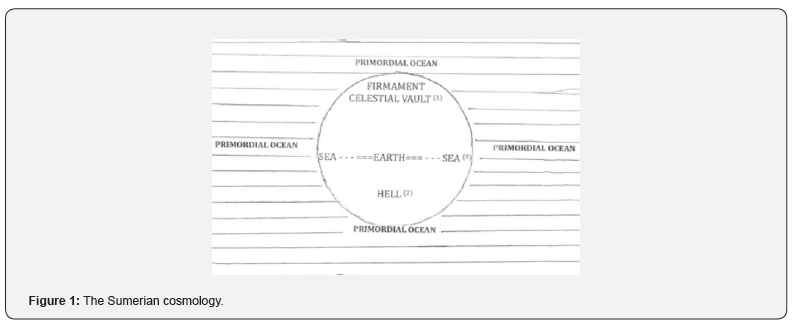

Around 2300 BCE, Sumerian scholars thought they were in the center of a flat world surrounded by the terrestrial sea, located between the celestial vault and the lower hell. The whole was encompassed by the primordial ocean (Figure 1) [1, Ch. 12].

1) Residence of the Gods (with capital letters, given their Gods were not inferior to ours).

2) Residence of evil forces.

3) The earth surrounded by the sea.

In The Histories the Greek historian Herodotus (484-425) was ironic about Homer (late 8th century BCE): “To talk about the Ocean is to replace any explanation with an obscure fable […] I think that Homer invented this name in order to use it in his fables [2, Book 2, 23]. We owe Sumerians the “Map of Nippur” which is engraved on a clay tablet dating from 2300 BCE [1, Ch. XXV]. The unknown was inspiring fear. For the Romans, the further away the people were, the more inferior they were. The Greeks used to name “barbarians” those who did not speak Greek. Herodotus reports that for the Persians, people far away were less estimable [2, Book 1, 134]. The Sumerian cosmology and the map of Nippur can certainly be interpreted as attempts at spatial modeling of nature, the main objective of which was the understanding of the complexity of nature.

How to Define Space

Space has multiple significations, as we can see in the following examples:

• “She needs some space” means “She needs room”.

• “They travel through space” means “They travel beyond the earth”.

• “Space conquest” means “Flight to other planets”.

• “In the space of a few seconds” means “During a matter of seconds”.

Our Aim is not about mathematical spaces, but about the physical space which is to be defined from naturalia (from the Latin “naturalis”: natural part).

What are we talking about, when we use the word “space”? To define a thing is to say what that thing is. This is why we have no choice; we must define it.

Thanks to Latin literature, we can accurately observe the progressive enriching of the language of spatiality through new words and expressions. Here are some examples.

• In Cicero (106-43):

• “communia spatia” (common spaces). Ex: a public square).

• “dimensior” (dimension).

• “disto” (be away).

• “spatium” (place, space).

• In Lucretius (98-55):

• “altivolans” (high-flying).

• “in alto” (high up).

• In Cæsar (101-44):

• “altus” (high).

• “crassitudo” (thickness). Ex: “The thickness of a wall is what is between the sides of the wall”.

• “spatium” (space).

• In Virgilius (c.70-19 BCE):

• “aether” (sky).

• “volvo” (roll).

• In Augustus (63 BCE-14 CE):

• “distensio” (extension).

• “longiquinquo” (far away).

• In Titus Livius (c.59 BCE-17 CE):

• ‘’demetior’’ (lower).

• ‘’trans’’ (across).

• In Ovidius (43 BCE-c.17 CE): “spatior” (more spacious).

• In Columella (early first century CE): “superficies” (surface).

• In Seneca (c.4 BCE-65 CE): “spatiosus” (spacious).

• In Florus (First century CE): “longiquitas” (distance). Ex: “what is between the two houses”.

• In Plinius Caecilius (61-c.114):

• “distantia” (distance) “what is between two cities”.

• “longiquus” (distant).

• “longule” (long).

It results from this list that the word “spatium” was originally used to designate a place, a public square, then a large square, a clear place. It leads to elementary definitions such as:

• Space is what is between me and an object in front of me.

• Space is what is between two stars (Figure 2).

• Space is what separates two things.

These definitions are quite approximate, but what they say is true. In addition, they will provide theoretical extensions to take into consideration.

First Units of Space

Herodotus specifies the distances travelled or to be travelled by using “day’s walk”, “day’s sail”, “month’s sail”, which is helpful because it also says how long the travel will last.

The Latin philosopher Lucretius (c.96-55) uses metaphorical units: “at range of an arrow” and “within the reach of a javelin throw” [4, Book IV, 409]; helpful too for strategists.

The Latin poet Petronius (?-65 CE) uses “the flight of a kite” [5, XXXVI].

Properties of Space

No experiment on space can be carried out. Let’s confirm through three attempts of experiment: observation, measure and relativistic covariance.

Space is not observable

What happens if we remove the objects which have been used to define space?

Let’s observe carefully the Figure 3, and make an imaginary simulation which consists of removing all the objects: the sea, the sky including clouds and sun rays, the ocean liner with its smoke, and the channel dredger behind.

We can’t see anything anymore; in other words, space is not observable as such.

“Empty space” is a pleonasm, because space as such is empty.

Space is not measurable

Can we measure the length of an object? In fact, we measure what is between the two ends of the object, not the length. For example, we don’t measure the “length” of a ship: instead, we measure what is between the bow and the stern; the result is called “length of the ship”. Indeed, “length” does not exist in itself; it’s a mathematical concept.

The relativistic covariance

Let’s imagine two relativistic systems: a signal transmitted in one is different from the same signal received by the other. This covariance concerns all parameters. The covariance of the length (the space at large) is the variation of the value of the length when passing from a relativistic reference frame to another. The covariance of the length is not an experiment on space. Instead, the experiment is carried out on the objects used to set length [3].

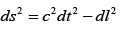

The opposite of the covariance is the invariance. For example, the speed of light “c” is invariant. In 1905, Einstein invented the invariant concept of space-time “ds”, such as

“ds” has no physical existence, it’s a pure mathematical concept.

Space has no physical properties

No color, no mass, no weight, no dimension, no electric charge, no speed, no gravity; in one word: no materiality. Space is devoid of physical properties; it’s a mathematical concept, without physical existence. It only owns mathematical properties.

Mathematical properties of space

Let’s remind the properties deduced from the definitions according to each field of physics:

• In classical physics, space is continuous, determinist, invariant.

• In relativistic physics, space is continuous, determinist, covariant.

• In quantum physics, space is discontinuous, probabilistic, invariant.

• In quantum and relativistic physics, space is discontinuous, probabilistic, covariant.

• We observe that space is a polymorphic concept [3].

Felt space

In 2022 we have introduced the concept of felt time, and explained through psychology why durations of the same event seem to last more or less long, depending on the activity. It’s the same case with space: vertigo, claustrophobia are current examples of felt space. We are deceived by technical effects of field [6]. It’s the domain of psychology.

The Dichotomy Time & Space

It comes to dichotomy (from the Greek “dikha”: in two; and “tomos”: portion) and not dialectic (from the Greek “dialectikê”: art of discussion).

Time and space are both invention of thought; they have the same mathematical properties. They are mathematical concepts. They give birth to speed, which is modelized.

From the analysis of (2), can we identify the cause of the distance travelled?

• Either the “duration”: it’s impossible, because “duration” is not a phenomenon; it’s the time indicated by a clock. Even if I break my clock, time keeps passing.

• Or the “speed”: that’s right, because it’s the only active factor.

In this type of analysis, one must be wary of field model effects: (3) let’s think that “v” and “t” play the same role, what is wrong. The speed of light “c” is a physical constant to which one can refer for long distances because it gives the distance and the duration:

• The Moon is at about 380 000 km (1.25 light second). The light needs 1.25 second to reach us.

• The Sun is located between 144 and 162 106 km; between 8 and 9 light minutes.

• The star Proxima Centauri is about 4.25 light years far from us. One sees Proxima like it was 4.25 years ago.

• Andromeda galaxy is at about 2.5 million light years: a radio message will reach Andromeda in 2.5 million years.

• The further we look, the further back we go in the history of the Universe.

The Failure of Stephen Hawking

The classical way of observing the sky from further and further away is called bottom-up cosmology (or ascending cosmology). Through a top-down cosmology (or descending cosmology), Stephen Hawking starts from the Big Bang; he asserts, with no proof, that the Big Bang results from “a cosmic intention”. “Time changes into space as we approach the beginning”. “A space nucleus is the origin of time”. “Laws of physics are conducing to life”. “Physics is supposed to prove that divine foundations are at work” [7]. This very impressive metaphysical drift is the obvious result from the ignorance of the nature of time and space, and the inability to define these concepts, despite the title of one of his previous books [8].

Conclusion

The more obvious a topic seems, the more difficult it is to theorize. The problem of space is even more difficult to solve than that of time. Thanks to a multidisciplinary approach, in the same way as for time, we have succeeded in defining space and identifying its nature. We agree with that, our definition of space is poor, but there are no others. In addition, this made it possible to discover some properties, quite heterodox. Contrary to general opinion, space has no materiality; it’s a mathematical concept. This result shakes up our habits of thought, all the more so since space is a protected and reserved topic; and above all, a sensitive topic, because like time, space was invented by Gods. But knowledge is not subversive; it only threatens ignorance.

References

- Kramer S (1957) L'Histoire commence à Sumer (The history begins in Sumer) (Artaud 1957).

- Godley AD. Herodotus: The Histories.

- Dassonville FP (2017) The Invention of Time & Space, pp. 1-176.

- William Ellery Leonard. Lucretius: de rerum natura.

- Caius Petronius Arbiter. Petronius: Satyricon.

- Dassonville P (2022) The Enigma of Felt Time in EC Psychology and Psychiatry. ECronicon, London.

- Hertog T (2023) On the Origin of Time: Stephen Hawking’s Final Theory. Bantam Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

- Hawking S (1996) The Nature of Space and Time. Princeton University Press.