The Killed Vessels: Background, Modalities and Possible Meanings in the Prehispanic Cultures of Northwest Argentine

Emanuel Moreno¹ and Mario Caria²*

1Institute of Geosciences and Environment, Archeology and Museology Group of the Lowlands of Tucumán, Faculty of Natural Sciences and IML, UNT, Argentine

2Institute of Geosciences and Environment, Archeology and Museology Group, CONICET, Argentine

Submission: March 01, 2024; Published: April 15, 2024

*Corresponding author: Mario Caria, Institute of Geosciences and Environment, Archeology and Museology Group of the Lowlands of Tucumán, Faculty of Natural Sciences and IML, UNT-CONICET, Argentine

How to cite this article: Emanuel Moreno¹ and Mario Caria²*. The Killed Vessels: Background, Modalities and Possible Meanings in the Prehispanic Cultures of Northwest Argentine. Ann Rev Resear. 2024; 11(1): 555804. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2024.11.555804

Summary

In this work we analyze the different modalities and meanings made on the so-called “killed vessels” present in the pre-Hispanic groups of Northwestern Argentina (NOA). To do this, we first start from the study and the meanings given to them throughout the American continent, and then focus on the specific case of the pre-Hispanic Candelaria style.

Keywords: Killed vessels; Prehispanic; Indigenous worldview; Argentine Northwest

Introduction

This analysis is based on the idea that the various forms of expression that human beings have to represent the features of their worldview can often seem strange to the eyes of other human beings. Thus, depending on the view that underlies the field of each subject on their interpretation of life and their environment, the materiality with which it is manifested will also depend. Therefore, while some play with realities that can be literally understood (such as the use of words or sounds), others play with features or representations that require an interlocutor, either the creator of those features or a specialist who will try to, mediated by temporal distance, understand them and translate them into a discourse capable of filling it with meaning (although many times those meanings may be arbitrary). In this sense, the rites with which different cultures, both present and past, have manifested the active part of their worldview, stand as a field that requires, in most cases, a careful study for its best and logic interpretation. As the philosopher Byung-Chul Han [1] expresses it well in his essay The Disappearance of Rituals, rites are symbolic actions and keep a certain community together, at the same time that the symbol, which serves to recognize itself, also serves to perceive itself. In the same way, Han states that rituals “being a form of recognition, symbolic perception perceives what is durable” and with this “the world is freed from its contingency and is granted permanence”. And if we consider that rituals grant permanence to those beings or those others who are no longer there, rituals make, in Han’s sense, “time habitable”, “they order time and condition it”, that is, “Rituals give stability to life.” That is why this essay makes sense when talking about a part of the worldview of the pre-Hispanic Candelaria culture in the Argentine Northwest, such as “killing the vessels,” that is, ending a cycle and beginning another., in a ritualization that compromises not only the material but also the spiritual. Kill so that something else comes to life and give life so that what is killed gains meaning. A circle that demands, beyond the object that is killed, its immaterial side, its counterpoint so that what must be closed can continue on the other plane. And it is precisely, metaphorically speaking and literally shown, through a circle (hole, orifice, etc.) that one of the ways of beginning and concluding a cycle is ritualized; to make the transition from the symbolic to the practical viable.

This work aims to give dimension to a specific ritual, linked to pre-Hispanic cultures, and even in current societies that continue to practice it. Killing one or more vessels implies, as we will see later, drawing a bridge between what is seen and what is not; between what you want to let go and let it remain; between the human and non-human; between the intangible and physicality. Killing in the symbolic and factual sense, so that what was ceases to be and. At the same time, continues to be, but on another level, in another place and at another time. The terminological glossary for the study of archaeological ceramics defines “killed vessels” as a “term applied to ceremonial ceramics, associated with burials, that present one or more perforations” and that can be interpreted as part of “the belief that “the “soul” of the vessel will accompany that of the dead and like the ritual destruction of ceramic objects” Heras and Martínez [2]; Martínez de Velasco Cortina [3]; Testard [4]. The term killed to have been adopted in a general way, referring to vessels intentionally fragmented, their supports cut or pierced, through a blow or with some tool. Other authors consider that this demonstration is intended to nullify the function of these containers as containers. From these general notions we will seek to complicate and put into context the situation of archaeological objects and ceramic vessels killed in some sectors of the American continent and the interpretations of which they were part throughout time and space, and then return to them in our analysis for Candelaria.

It is important to highlight that there are very few works that made a synthesis of this practice in the pre-Columbian past of America. However, this analysis does not pretend to be a catalog of all the cases recorded throughout the continent; rather it seeks to provide a regional and interpretative framework that allows carrying out an exercise of approximation towards the importance and meaning of the practice of killing objects in archaeological contexts. This will be of vital importance for the analysis, contextualization and interpretation of the “killed vessels” from the NOA archaeological collections. We will pay special attention, as we already mentioned, to the ceramic vessels of the Candelaria style, some of which have a series of perforations in various parts of their body. Given the recurrence of its appearance and the evident symmetry of the holes observed, we believe that this practice would be present in Candelaria and other ceramic styles of the NOA during the period 1000 years BC. - 1000 years AD. C.

The vessels killed in the American continent and the NOA

On the American continent there are numerous examples of this practice, from the potlatch rituals practiced in groups of the Pacific coast in the northwest of North America, or the funerary rituals practiced by societies of New France (Iroquois of the Great Lakes and the Saint- Laurent and Micmacs of the Atlantic coast) during which some containers may have been ritually killed, nullifying their container function. Other North American peoples, such as the Zuñi, practiced intentional perforations in their vessels during funerary ceremonies, while other groups carried out the intentional destruction of ceramic objects as offerings at sites in the Chaco Canyon Testard [4]; Cushing [5]; Toll [6]. In Mesoamerica, this practice has been documented from the Preclassic period (2500 years BC) to the present. There are also cases of intentional destruction of vessels, ceramic sculptures and archaeological objects in settlements such as Teotihuacán, sites of Cerro Barajas, Guanajuato and Milpillas (Mexico) and the site of Nakum (Guatemala), which were interpreted as rites of abandonment of structures and pre-Hispanic peoples. On the other hand, numerous examples of killed ceramics associated with human remains were detected in funerary contexts in the Mayan area of Mexico and Guatemala Migeon [7]; Koszkul [8]; Carot and Hers [9]; Manzanilla [10]; Ortiz and Manzanilla [11]; Tovalín Ahumada and Ortiz Villarreal [12]; Pellecer Alecio [13]; Martínez de Velasco Cortina [2].

In South America the panorama is no less complex and offers various cases that could illustrate this custom. During the early occupations of the Cauca River valley (500 years BC-500 years AD) the burial of an individual with killed ceramics is mentioned, which was fragmented and scattered around the body of a person interpreted as a possible shaman. During the Early Formative on the Ecuadorian coast, offerings containing ceramic figurines from the Valdivia culture, intentionally fractured, were recorded at sites such as Real Alto and Rio Chico. In Río Chico, offerings were presented with faunal remains associated with fifteen intentionally broken figurines, five vessels and ceramic fragments where the nature of some killed figurines from Valdivia seems to respond to a ceremonial activity linked to cosmogonic myths Rodríguez Cuenca [14]; López Reyes [15]; Kaulicke [16]. In pre- Hispanic Peru, there are known cases of vessels intentionally fractured and deposited as offerings in specific places in the south-central mountains and the southern coast. An example of this emerges from the analysis of a set of ceramic materials in the Huaca del Sol and would correspond to the well-known tradition practiced in other parts of Peru during the Middle Horizon, which consisted of intentionally breaking vessels as part of an offering Kaulicke [17]; Uhle [18].

The presence and use of ceramics in the ritual context is well known in Andean antiquity. DeLeonardis [19] maintains that in addition to the Moche, other groups such as the Huari broke some of their finest vessels in situ. Ceremonial libations and sponsored banquets were also prevalent in rites performed by middleranking societies and left their mark on intentionally destroyed pottery. The same author carried out an analysis of the Paracas area of influence, where she evaluated four ways in which offerings are made: ritual burning, fragmentation, deposition of offerings in pairs and miniature ceramics. In a residential site in Callango, vestiges of rituals in which fragmented ceramics were burned were found. These offerings are believed to symbolize a particular request or belief. In the dispatch packages of these offerings, other exotic and sumptuary elements appear associated, where some related to magic, divination and terrestrial/aquatic fertility stand out. According to the author, fragmented and unburned ceramics constitute a significant offering in the Paracas tombs. This custom was recorded in the tombs of Teojate in the Ica Valley and in the tombs of Ocucaje, in which sherds or fragmented vessels associated with the burials were found. At the Las Cavernas cemetery on the Paracas peninsula, fragmented pottery was carefully placed with the deceased. Fragments of plates and perforated potsherds were found in some funerary bundles DeLeonardis [19].

In Amazonia there are numerous examples of ceramics killed during the 1st and 2nd millennium AD. There are hundreds of Marajó ceramic figurines recovered in funerary contexts and ceramic fragments in domestic garbage dumps. The statuettes belonging to the Marajoara ceramics have a characteristic break in the neck to separate the head from the body. The fragmentation would be intentional, since the necks of the figures have thick walls, so fragmentation due to structural weakness is very unlikely Barreto [20]. In Amazonia there are numerous examples of ceramics killed during the 1st and 2nd millennium AD. There are hundreds of Marajó ceramic figurines recovered in funerary contexts and ceramic fragments in domestic garbage dumps. The statuettes belonging to the Marajoara ceramics have a characteristic break in the neck to separate the head from the body. The fragmentation would be intentional, since the necks of the figures have thick walls, so fragmentation due to structural weakness is very unlikely. In the lower region of the Tapajós River (a tributary of the Amazon River) archaeological contexts were recorded with Santarém ceramics, which would have been used in collective ceremonies and in rituals of fracture and burial of said objects to eliminate any power or agency thereof. The Santarém figurines can be considered as part of a complex set of ceremonial ceramics heavily charged with symbolic meanings and subjective powers of agency. On the other hand, some vessels from the Paredão phase (central Amazon) were fragmented or perforated at their base before being deposited in archaeological contexts. On the other hand, the practice of destroying personal objects was observed in ethnographic contexts in Brazil; for example, the Kayapó destroy the belongings of the deceased for various reasons Turner [21].

Ceramics from the Wankarani cultural entity (2000-100 years BC) from funerary contexts and mound structures were analyzed in mounds of the Bolivian highlands. The vessels appear killed with intentional holes, made as part of a specific ritual. Clay figurines generally appear fractured, some of which would show no signs of wear. The latter, added to the miniaturization of other ceramic pieces, leads the authors to suggest that the ceramics would be part of a set of offerings in ceremonial and festive contexts. These would be common in the sphere of interaction that would include other parts of the Bolivian highlands and northern Argentina and Chile. During this period “a common ceremonial “language” is being established, promoted by a growing interaction between the southern Andean populations” Ayala Rocabado and Uribe Rodríguez [22]. On the other hand, a vessel with zoomorphic decoration from the Montevideo site in the Machupo River area (Beni department, Bolivia), exhibits a symmetrical perforation on its surface, which could be due to intentional perforation Betancourt [23]. In Chilean territory we observe a strong recurrence in a variety of contexts from archaic times to the Inca expansion. In the temple of Tulán-54 (1110- 360 cal. BC) killed objects were recorded: ceramics, lithics and fragmented metals, perforated and/or associated with ritual burnings, together with sacrifices of neonates and camelids. This set would be part of offerings, feasts and propitiatory rituals dedicated to deities and tutelary ancestors of the communities of the Puna de Atacama in order to avoid adverse reactions. Similar offerings were recognized as payments in early formative-archaic temples on the coast of the Central Andes Núñez [24]. During the Early Intermediate Period, in the middle and lower reaches of the Aconcagua River (central Chile), mortuary practices associated with the destruction of pieces and scattering of fragments in burial sites or intentionally fractured incomplete vessels (El Bato and Lloleo cultural complexes) are recorded. In other cemeteries in central-southern Chile, two methods are recognized to render pottery artifacts useless: total or partial fracture and perforation of the body or bottom. In the Gorbea cemetery it was discovered that in some cases the fragments were piled up and in others scattered on one or both sides of the body. In another case, “a fractured duck jug was found next to a corpse, on which two heavy basalt stones lay, evidencing its intentional fracture” Saunier and Avalos [25]; Gordon [26,27]. In other graves in the region, vessels with discoidal perforations in the body or bottom were recorded. The intentional breaking of objects in the funerary rite is a millenary tradition in the region and is archaeologically documented from the early moments in the Huimpil cemetery to the late Gorbea necropolis.

Other cases of perforated vessels are also known in Calama and Atacama Latcham [28]. For example, during the Late Intermediate Period (900-1350 years AD) in the Calama-Quillagua transect (Atacama Desert) offerings of fragments of killed ceramics accompanied by other elements and deposited in ceremonial structures and geoglyphs from caravan contexts are observed. The discovery of basal perforations in vessels from the Diaguita culture is also reported, which would be associated with mortuary rites Correa and García [29]; Román Marambio and Cantarutti Rebolled [30]. During Inca times, at the Pedelhue site (northern sector of the Colina Commune) partially fragmented pieces and intentionally pierced vessels were recognized and identified as killing practices constituting funerary offerings Hermosilla [31]. The logic of the death of a piece is applicable to other types of artifacts, intentionally fractured or pierced, in funerary or propitiatory contexts in Chile Román Marambio and Cantarutti Rebolledo [30].

In the northeastern region of Argentina, it is recognized that the practice of destroying ceramic vessels and objects is common. It is also “known that the aborigines of Paraná had the habit of breaking their glasses and then scattering the fragments.” Also for the groups on the Paraná coast it is reported that “the habit of intentionally fracturing the vessels they left behind, and even dispersing the fragments later, has made the discovery of any of them in their entirety extremely rare” Ceruti [32]; Cornero [33]; Aparicio [34]; Iribarne [35]. In ethnographic contexts the practice has been widely recorded. In the Chaco region, the practice that included breaking ceramic vessels was very common since “in most Chaco groups the personal effects of the dead were buried with him or destroyed or burned. These actions were inspired by the desire to provide the spirit with its familiar and necessary objects, as well as by the fear of its return to claim its goods” Méndez and Ferrarini [36].

On the other hand, since the end of the s. 19th and early 19th centuries XX, cases of killed ceramics were reported in archaeological contexts of Northwestern Argentina (NOA). Its presence was first recognized in the Calchaquí valleys and in the lowland area. Ambrosetti identified the perforations in ceramic fragments from Pampa Grande (Salta) as the product of intentional perforations executed during an ancient funerary rite. When Ten Kate [37] related the breaking of the NOA materials with ritual practices known in North American groups, she was struck by the frequency of these holes and these breaks, concluding that they were cases associated with the action of killing the ceramics. Rydén [38] mentions the funerary urns recovered from the materials excavated in La Candelaria (Salta), some of which exhibited perforations in the bottom, which is why they were interpreted as killed pieces. In the Puna of Jujuy there is reference to a funeral ritual that consisted of opening holes in the bases of the vessels, which were deposited as offerings. In a funerary context at the Punta de la Peña 9 site (Antofagasta de la Sierra) the presence of a Candelaria style funerary urn with “death holes” is mentioned Juárez [39]. There are also other contexts where the presence of the practice corresponding to the intentional destruction of ceramic containers for various purposes is recorded. A particular case is the ceramics killed as part of offerings in ceremonial mound structures (fragmented and/or burned, accompanying various types of objects, some with a strong ritual charge, faunal and human remains) in Alamito, Tafí, Ambato and the foothills south of Tucumán González and Núñez Regueiro [40]; Tartusi and Núñez Regueiro [41]; Srur [42]; Núñez Regueiro and Tartusi [43]; Laguens [44,45]; Miguez [46]; Miguez and Caria [47]; Miguez [48]; Miguez [49].

During the 1st millennium AD, in the Tafí valley, sacrificial offerings were reported in funerary contexts and in founding acts of agricultural structures that included camelidae remains, lithic figurines and fractured ceramics Salazar [50] and [51]; Franco Salvi and Salazar [52,53]. An example of this is an offering placed in the cultivation sector of the La Bolsa 1 site, which consisted of a semicircular stone structure that covered camelidae bone remains and ceramic fragments. The event was dated between 70 and 220 AD. This offering would have been the protagonist of the founding act of the structure. According to the interpretations given, these events would be associated with ritual festivities and are analogous to others observed in various sites on the continent from pre-Inca times to current times. It is believed that a large part of the ceramics offered were part of the daily activities of the pre-Hispanic groups of the Tafí valley. On the other hand, there is knowledge of domestic contexts in the mountains of El Alto Ancasti and practices of abandonment of settlements in the Ambato valley (La Rinconada site) where killed ceramics make their appearance Barot [54]; Gordillo [55]; Gordillo Vindrola- Padrós [56,57]. Specifically for Candelaria materials, Alberti [58] proposed an ontological equivalence between vessels and bodies of flesh. For his part, Lema [59] expanded these notions and recognized the importance of the breaking of bodies and ceramic objects in funerary contexts of Candelaria as a means of moving to another plane of existence. Following this logic, the urns are not killed to nullify their function as containers, but rather they are topologically altered to reverse the order of things.

The basis of our analysis

To study the killed vessels of the Candelaria style we work with both private and public collections. We took into account aspects such as their origin, the shape of the vessels, their decoration, sizes, the identification of beings represented, among others, and all this information was integrated into a digital database. The material basis of our analysis is based on the survey of sixteen collections from the Argentine Northwest (Tucumán, Salta and Catamarca). For all of them, the following were carried out: 1) critical analysis of archaeological and ethnographic sources and antecedents; 2) development of nomenclature for collections and archaeological pieces and personalized registration sheets; 3) registration of pieces with photographs, drawings, files and particular notes. Consultation of information in databases about the pieces of collections analyzed, 4) digitization of data. On the other hand, the study of morphological and anatomical characters was carried out that served to identify groups of beings represented (fauna, flora, humans, others) in the ceramic objects and thus be able to establish some type of preferences or not on the object chosen to be “killed”.

Results

Types of killed pieces

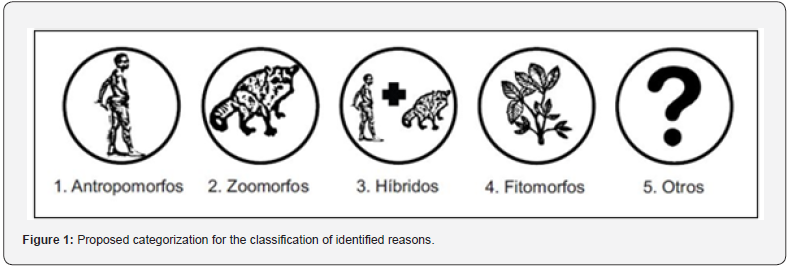

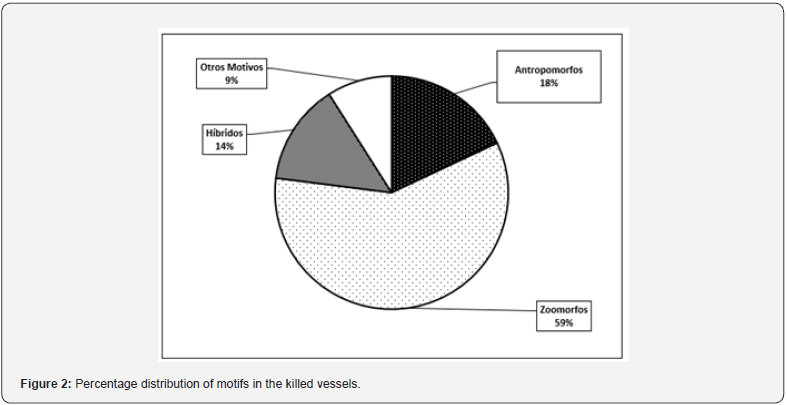

As a result of the analysis of the collections, a total of 124 pieces were counted. On the other hand, the identified representations were grouped into five broad categories: 1) anthropomorphic motifs; 2) zoomorphic motifs; 3) hybrid motifs (anthropozoomorphic hybrids and zoomorphic hybrids); 4) phytomorphic motifs and 5) others (Figure 1). Practices aimed at manufacturing bodies were recognized: tattoos, piercings, tembetás and other body adornments. Beings in an apparent process of transformation and metamorphosis were identified. Regarding zoomorphic motifs, new taxa and species could be identified for representations of Candelaria and related styles from the first millennium, among them: indeterminate zoomorphs, mayuates, ornithomorphs, anurans, strigiformes, camelids, foxes, felines, bats, snakes and flamingos. Other motifs identified were the tapir, the quirquincho, the deer, the alligator and the turtle. Of the total number of pieces analyzed, we observed, at a macroscopic level, that 17% of them exhibited fractures in the form of perforations and holes. Some of these pieces come from funerary contexts, while others do not have contexts of provenance. The recurrence of these perforations, as well as the clean fracture of their execution, leads to the assumption that there would be an intentional nature to them. We must clarify that, although we focused on the analysis of pieces of the Candelaria style, in other observations we were able to verify the presence of holes in late ceramic pieces of the Santa María style (900-1470 years AD). As a result of the distribution of fractures, according to the categorization of reasons, we obtained the graph in Figure 2.

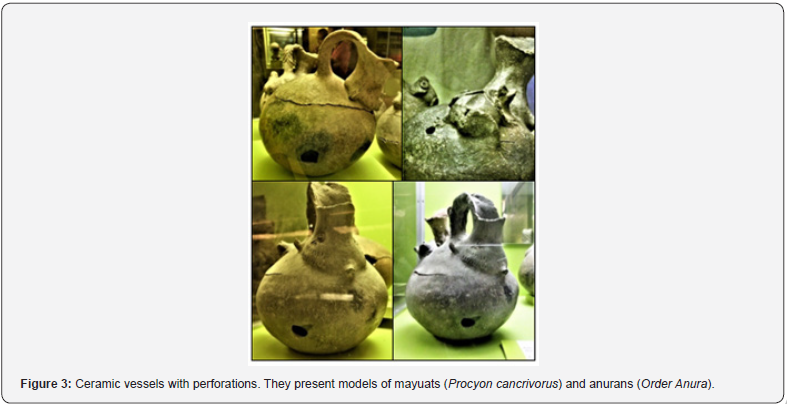

In the “other motifs” category, pieces without decoration (50%) and with geometric decoration (50%) were recorded. Among the hybrid motifs we find two types of anthropozoomorphic hybrids: the first type is the result of combined traits of human and mayuato (Procyon cancrivorus) (33%); the second is the result of the combination of human and ornithomorphic traits (67%). In half of the anthropomorphic representations, tattoos were recorded on the face or body of the beings present in the pieces. Finally, within the percentage of zoomorphic motifs (59%), the presence of the following subcategories could be recognized: mayuato (35%), ornithomorph (29%), indeterminate zoomorph (14%), anurans (7%), flamingos (7 %) and turtles (7%). Regarding the method of killing vessels, holes of variable size (between approximately 2 to 30 mm) and diverse morphology were recorded. Most holes show a clean fracture. Only two cases of partial fracture in the bottom of vessels are recorded, which we believe belong to funerary urns. Our analysis focuses on the vessels that have representations and that presented clean perforations, which could indicate an intentional breakage intended to destabilize the physicality of the pieces (Figure 3).

Discussion

From the analysis of the cases presented for the American continent and the NOA in particular, we can say that, despite the fact that the phenomenon of killed vessels is present from the beginning of the agro-pottery period until present times in various regions of the continent, with different modalities and purposes, specific and/or synthesis works dedicated to understanding this problem are scarce. Based on the aforementioned background, in the context of archaeology, we understand by killing pieces any intentional act aimed at destabilizing the physicality of an archaeological piece partially or totally, through the execution of one or multiple fractures - or another procedure physical - that causes the alteration of the function - or functions - for which it was originally conceived. This act is observable in physical terms, but we assume that its effects have metaphysical consequences in the life of pre-Hispanic communities, and the latter would be an important driver of destabilization for the materialization of said practices in pre-Hispanic societies of the 1st millennium AD. According to our observations, we identified four modalities for killing vessels throughout the American continent and the NOA: 1) partial breakage of the piece; 2) total breakage of the piece; 3) through perforations in the body of the vessel and 4) through the use of fire.

In turn, these modalities are not exclusive and can be accompanied by other features that would effectively reinforce the identification of a vessel death event and allow a precise characterization of it:

a) Location of the piece: the contexts of manifestation of these phenomena are multiple. For this essay we define three contexts of analysis: residential, public ceremonial and funerary.

b) Elements associated and potentially usable to carry out an intentional breakage of the vessels, for example, rocks or sharp devices.

c) Relative spatial location of the vessel within the archaeological context, for example, a vessel coming from a funerary context and placed upside down may imply a cancellation of its use as a container.

These modalities and features can appear in different combinations and are a first step for the interpretation of killed vessels - in conjunction with other objects - in an archaeological context. At the same time, it constitutes a preliminary approach for the interpretation of these practices in archeology and comparative ethnography. Based on the characterization proposed for the description of killed ceramic objects, we can define the analyzed sample as follows. Regarding the method of killing vessels, all the pieces (with the exception of the cases mentioned) show the third mode of our classification: perforations in the body of the vessel. On the other hand, depending on their location, some pieces come from funerary contexts, while others have no context of provenance. On the other hand, based on ethnographic cases, we can hypothesize that the main reasons for the destruction of objects in funeral contexts in our region may respond to the following beliefs: 1) as part of an operation to find out the causes and causes of death; 2) to free the spirit of the object and accompany the deceased to the afterlife and 3) to prevent the spirit of the deceased from returning for their objects and causing another death.

In this context, Alberti [58] proposes, for example, an ontological equivalence between bodies of flesh and ceramics in the Candelaria and San Francisco styles. In them, concerns are observed regarding the manufacturing of bodies and relatives to avoid ontological predation that would manifest in illness and death; these practices become especially visible during moments of social crisis. In another sense, Lema [59] discussed the importance of the destruction of bodies and materials as a mechanism of transformation in Candelaria funerary contexts for a retopologization of human and non-human bodies. On the other hand, the Candelaria materials were interpreted in their role as representations of shamanic transformations or ontological predations. Also, other possible functions were proposed for them: in magical operations for the regulation of meteorological processes and the reproduction of flora and fauna; as bodies of perspectives that can be adopted by shamans and witches to achieve their goals; to accompany the deceased in his ontological predation; as perspective markers used as a bodily reference to be aware of the body that people were inhabiting and as part of sacrifices to return vital energy to the community and avoid dangers to it Moreno [60]. All these approaches are denoting diverse roles for the Candelaria vessels, which go beyond mere representation or their function as containers.

In funerary contexts they can also be interpreted as a sacrifice intended to recover the vital energy poured during its manufacture as a relative. Predating the ceramic body (by stabbing or dismembering its parts) represents the end of a life cycle that begins with the manufacture of a ceramic body and its destruction, to be buried alongside a human and other non-human being. The orifice would operate as a means for bodily and ontological transformation. In this sense, it is important to note that the drilling of skulls, the breaking and dismemberment of bodies is present in Candelaria funerary contexts Lema [59]. On the other hand, the recombination of new bodies with human, animal and plant parts is also present in hybrid figurations recognized in their iconography Alberti [59], [61]; Alberti and Marshall [62]; Moreno [60]; Moreno [63,64].

Alberti [58] maintains that the fabrication of bodies and relatives in the Candelaria and San Francisco styles was carried out through practices such as cutting, shaping, and pinching. They would be ontologically equivalent to those executed in bodies of flesh. We believe we have recorded the practice of destroying bodies in the holes of the killed Candelaria vessels by drilling the ceramic bodies. We consider that piercing, beheading and dismembering constitute ontologically equivalent actions for the destruction of bodies of flesh and clay in many cases in the region, whether as part of rituals for daily life, as a sacrifice during the death of its members and /or as ceremonial offerings. These practices constitute complex mechanisms for the activation of the time wheel of non-Western societies, with a particular conception of the energy flows of the universe. Possibly this logic has broader scope, however, the present discussion is far from being resolved. Future analyzes will be able to better characterize the nature of the holes observed in this and other ceramic styles from the NOA and other regions of the continent where they are present [65-72].

Continuing with our discussion, we observe that the practice of vessel killing in the Candelaria style is represented in a wide variety of ceramic pieces. The holes in the body of the vessels are figured in all the proposed categories, with the exception of phytomorphic motifs. However, observations made on other Candelaria pieces corroborate the presence of holes in vessels with plant motifs. Taking the above into account, we can affirm that there would not be an exclusivity to kill vessels according to the beings incarnated in the ceramic pieces. As for the rest of the categories, a clear predominance of zoomorphic motifs is observed. Among these, the most represented groups were mayuatos and birds, which tell us about the importance of their representation in quantitative terms. The appropriation of bodily characteristics and temperaments of said faunal groups would be part of the varied motives selected, both for their creation and for their bodily destruction.

Based on observations from previous research and our own interdisciplinary work developed on the materials and contexts of Candelaria, we propose the existence of subjectivities embodied in ceramic bodies as tulpa-beings. They would have had their own will linked to the life, death and rebirth of people in other worlds. Possessing an agency and a will, their intervention would directly affect the development of relationships between social subjects in various activities of sacred daily life. During some moments they could even become dangerous, for example, when their human companion dies and this should be killed as a sacrifice, taking advantage of their vitality for the generation of new human and non-human bodies. Following this logic, the predation of ceramic vessels has a component of physical and metaphysical causes and consequences for the life and death of the pre- Hispanic communities of northwest Argentina. We understand the assimilation of the physical and metaphysical properties of beings as a step and a necessary condition for the social existence of human and non-human communities, moving and generating metaphysical and everyday lines of action and perception.

Conclusions

The analysis of the practice of killing vessels throughout the American territory and the NOA in particular, allowed us to generate a general framework of approach to understand diverse logics around its practice and was useful to establish similarities and particularities from the case of Candelaria ceramic objects, as well as enriching the archaeological interpretative panorama of the region, and other problems surrounding the events of creation and destruction of objects present in the archaeological record. We consider that future analyzes on pieces of this and other ceramic styles could substantially define other dimensions of the practice of killing vessels in its drilling modality, which occurs almost exclusively in funerary contexts, as was observed in the ceramic pieces recovered from the archaeological El Cadillal (Tucumán) sites. Working with pieces from collections presents a series of advantages and limitations that must be complemented with other studies to establish comparisons and observe recurrences and particularities according to each case. Also, it allowed us to establish the different modalities of “killing vessels” practiced by different human groups in the past and in the different regions of our continent, allowing us to expand the bases for this type of practices, which are often overlooked by archaeologists, both at the level of the archaeological record and interpretations of social processes in the past.

References

- Han BC (2021) The disappearance of rituals. Herder Editorial.

- Heras CM, Martínez (1992) Terminological glossary for the study of archaeological ceramics. Revista Española de Antropología Americana 22: 16.

- Martínez de Velasco Cortina A (2012) Archaeological contexts of the killed vessels of the Mayan Area, in B. Arroyo, L. Paiz, and H. Mejía, XXV Symposium of Archaeological Research in Guatemala, Ministry of Culture and Sports, Institute of Anthropology and History and Tikal Association pp. 1213-1221.

- Testard J (2019) Performative sequences and ritual destruction of sculptures in Mesoamerica. Some hypotheses from Cacaxtla, Xochicalco and Cholula (Mexico) during the Epiclassic (600 to 900 AD), Americae. European Journal of Americanist Archaeology 4: 71-90.

- Cushing FH (1890) Preliminary notes on the origin, working hypothesis and primary research of the Hemenway Southwestern archaeological expedition. Compte-Rendu du Congres International des Americanistes de la Septieme Session 1888, Berlin, Germany pp. 151-194.

- Toll H (2001) Making and breaking pots in the Chaco world. American Antiquity 66(1): 56-78.

- Migeon G (2003) Planned abandonments, rituals of killed or closed vessels and subsequent occupations. The sites of Cerro Barajas, Guanajuato and Milpillas, in the Malpaís of Zacapu, Michoacán, Tracé Revue de Sciences Humaines 43: 97-115.

- Koszkul W Zralka J, Hermes B, Martin S, García EV (2007) Nakum Archaeological Project: Results of the 2006 Season, in J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo and H. Mejía, XX Symposium on Archaeological Research in Guatemala pp. 793-822.

- Carot P, Hers MA (2011) From Teotihuacan to Chaco Canyon: New Perspective on Relations between Mesoamerica and the Southwestern United States. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 33(98): 5-53.

- Manzanilla L (2018) The abandonment process of Teotihuacan and its re-occupation by epiclassic groups. Revista Trace 43: 70-76.

- Ortiz A, Manzanilla L (2018) Archaeological indicators of abandonment and recovery of the Teotihuacan housing complex of Oztoyahualco. Revista Trace 43: 77-83.

- Tovalín Ahumada A, Ortiz Villarreal V (1999) Bonampak offerings in funerary contexts, in J.P. Laporte and H.L. Escobedo, XII Symposium of Archaeological Research in Guatemala pp. 583-599.

- Pellecer Alecio M (2006) The Jabalí Group: An architectural complex with a triadic pattern in San Bartolo, Petén, in J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo and H. Mejía, XIX Symposium of Archaeological Research in Guatemala pp.1018-1030.

- Rodríguez Cuenca JV (2011) Worldview, shamanism and rituality in the pre-Hispanic world of Colombia: splendor, decline and rebirth, Maguaré 25(2): 145-195.

- López Reyes E (1996) The giant venus valdivia of Río Chico (OMJPLP-170a): southern coast of the province of Manabí, Ecuador, Boletín Arqueológico 5: 157-174.

- Kaulicke P (2016) Corporealities of death in the Central Andes (ca. 9000–2000 BC). Death rituals and social order in the ancient world: death shall have no dominion, en Colin Renfrew, Michael J. Boyd, Iain Morley, Cambridge University Press, New York pp. 111-129.

- Kaulicke P (1998) Max Uhle and the archeology of the southern coast, in Peter Kaulicke, Max Uhle and ancient Peru, Editorial Fund of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, Lima p. 47-65.

- Uhle M (2014) The ruins of Moche, Editorial Fund of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, Lima.

- DeLeonardis L (2013) The substance and context of the ritual offerings of Paracas ceramics, Boletín de Arqueología 17: 205-229.

- Barreto C (2017) Figurine traditions from the Amazon, en Timothy I., The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Figurines. Oxford pp. 417-440.

- Turner T (2009) Valuables, value, and commodities among the Kayapó of Central Brazil, en Fernando Santos-Granero, The occult life of things: Native Amazonian theories of materiality and personhood, The University of Arizona Press, Tucson pp. 152-169.

- Ayala Rocabado P, Uribe Rodríguez M (2003) Wankarani ceramics and a first approach to its relationship with the Formative period of the Norte Grande of Chile. Revista Textos Antropológicos 14(2): 7-29.

- Betancourt CJ (2011) The ceramics from the tributaries of the Guaporé in the collection of Erland von Nordenskiöld, Zeitschrift für Archäologie Außereuropäischer Kulturen 4: 311-340.

- Núñez L, Cartajena I, de Souza P, Carrasco C (2009) Early ceremonial architecture in the Puna de Atacama (Northern Chile), Boletín del Centro de Estudios Precolombinos de la Universidad de Varsovia 7: 305-336.

- Saunier A, Avalos H (2010) Funeral practices of the pre-Hispanic pottery populations of the middle and lower reaches of the Aconcagua River, Central Chile: traditionalism and change towards the end of the first millennium. VII Chilean Congress of Anthropology, San Pedro de Atacama, Chile 2: 823-848.

- Gordon A (1985) The interpretive potential of intentional fracturing and perforation of symbolic artifacts, Chungará 15: 59-66.

- Gordon A (2012) Huimpil, an early agro-pottery cemetery, Culture-Man-Society 2(1): 19-71.

- Latcham RE (1915) Mortuary customs of the Indians of Chile and other parts of America. Barcelona Printing-Lithography Society, Santiago-Valparaí

- Correa I, García M (2014) Ceramics and transit contexts on the Calama-Quillagua route, via Chug-chug, Atacama Desert, northern Chile, Chungara 46(1): 25-50.

- Román Marambio G, Cantarutti Rebolledo G (1998) Finding of basal perforations in Diaguita pottery: an approach from restoration and archaeological investigation of collections, Conserva 2: 81-100.

- Hermosilla NC, González D, Baudet (2002-2005) Peldehue Site: rescue of an Inka funerary context in an Aconcagua residential site, Xama 15-18: 263-278.

- Ceruti C (1983) Archaeological investigations in the Middle Paraná area - Entrerriana Margin. Acta Complementaria N° 2, Informe 1: 1982-83.

- Cornero S (2018) At the Gates of Myth: Parrots and Fish in the Ceramic Art of the Paraná River Coast (Middle Sector), en Gustavo Politis y Mariano Bonomo, Goya-Malabrigo: archeology of an indigenous society in northeastern Argentina, Editorial UNICEN, Tandil pp. 89-106.

- Aparicio FD (1937) Excavations at the whereabouts of Arroyo de Leye, Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología 1, p. 11.

- Iribarne EA (1937) Some indigenous vessels from the banks of the lower Paraná, Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología 1: 181.

- Méndez MG, Ferrarini S (2015) Symbology and temporal perpetuation in the Gran Chaco, Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano 2(3): 189-205.

- Ten Kate H (1893) Rapport sommaire. Sur une excursion archéologique dans les provinces de Catamarca, de Tucumán et de Salta, Revista del Museo de la Plata 5: 331-348.

- Ambrosetti JB (1906) Exploraciones arqueológicas en la Pampa Grande (provincia de Salta), Imprenta Didot de Félix Lajouane y Co. Buenos Aires.

- Rydén S (1936) Archaeological Research in the Department of La Candelaria (Prov. Salta, Argentina). Elanders boktryckeri aktiebolag, Guteborg.

- Juárez VB (2017) Ceramics and their social role in funerary contexts. PP9-III and PP13-I as case studies (ca. 1000-1300 years b.p.) (Antofagasta de La Sierra, Catamarca), Revista del Museo de Antropología 10(2): 35-46.

- González AR, Núñez Regueiro V (1960) Preliminary report on archaeological research in Tafí del Valle, NW Argentina, Proceedings of the XXXIV International Congress of Americanists, Vienna, Austria pp. 485-496.

- Tartusi MR, Regueiro V (1993) The ceremonial centers of the NOA, Publications p. 5.

- Srur F (1998) Analysis of the archaeological ceramics from the Casas Viejas mound. Tafi del Valle. Tucumán, Degree Thesis, Faculty of Natural Sciences and IML, National University of Tucumán, Tucumá

- Núñez Regueiro V, Tartusi M (2002), Aguada and the regional integration process, Estudios atacameños 24: 9-19.

- Laguens A (2004) Archeology of social differentiation in the Ambato valley, Catamarca, Argentina (2nd-6th centuries AD): actualism as an analysis methodology, Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología 29: 137-161.

- Laguens A (2007), Material contexts of social inequality in the Ambato Valley, Catamarca, Argentina between the 7th and 10th centuries AD, Revista Española de Antropología Americana 37(1): 27-49.

- Miguez G (2014) They shine in the jungle: context and technical analysis of gold objects found in a pre-Hispanic site in the foothills of Tucumán, Relaciones de la Sociedad Argentina de Antropología 39(1): 277-284.

- Miguez G, Caria M (2015) Landscapes and social practices in the southern jungles of the province of Tucumán (1st millennium AD), Pre-Columbian Material Chronicles. Archeology of the first settlements in the Argentine Northwest, Sociedad Argentina de Antropología pp. 111-148.

- Miguez G, Nasif N, Gudemos M, Bertelli S (2013) Birds, sounds and shamans. Interdisciplinary study of a bone musical instrument from a pre-Hispanic occupation of the southern jungles of northwest Argentina, Anales del Museo de América 21: 174-193.

- Miguez G, Caria M, Pantorrilla Rivas M (2014) Ceramic figurines in the life of the pre-Hispanic populations of the southern subtropical jungles of Northwestern Argentina, Revista Española de Antropología Americana 44(1): 39-63.

- Salazar J (2010a) Domestic social reproduction and residential settlements between 200 and 800 AD. in the Tafí Valley, Province of Tucumán, Doctoral Thesis, National University of Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina.

- Salazar J (2010b) Living with the ancestors. An analysis of burials in domestic contexts of the first millennium in the Tafí Valley, XVII National Congress of Argentine Archeology, Mendoza, Argentina, pp. 635-640.

- Franco Salvi V, Salazar J (2014) Llama offerings in an early village landscape: new data from northwestern Argentina (200 B.C.-A.D. 800), Journal of Andean Archaeology 34(2): 223-232.

- Franco Salvi V, Salazar J (2017) An offering as a founding act of cultivation structures. First millennium of the era in the Tafí valley (province of Tucumán, Argentina), en Beatriz N. Ventura, Gabriela Ortiz y María Beatriz Cremonte, Archeology of the eastern Surandean slope: macro-regional interaction, materialities, economy and rituality, Sociedad Argentina de Antropología, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires pp. 347-357.

- Barot C (2017) Vessels in daily life. Morphological-functional analysis of the ceramic material of a house located in the mountains of El Alto-Ancasti (7th and 8th centuries AD), Degree Thesis, School of Archeology, National University of Catamarca.

- Gordillo I (2004) Architects of the rite: the construction of public space in La Rinconada, Catamarca, Relaciones-Sociedad Argentina de Antropología 29, pp. 111-136.

- Gordillo I, Vindrola-Padrós B (2017) Destruction and abandonment practices at La Rinconada, Ambato Valley (Catamarca, Argentina), Antiquity 91(355): 155-172.

- Gordillo I, Vindrola Padrós B (2019) No return. Split subjects/objects, en A. Laguens, M. Bonnin, B. Marconetto, Book of abstracts XX National Congress of Argentine Archeology, Córdoba, Argentina pp. 1172-1175.

- Alberti B (2007) Destabilizing meaning in anthropomorphic forms from Northwest Argentina. Journal of Iberian Archaeology 9(10): 209-29.

- Lema V (2019) Containers, bodies and topologies: a comprehensive analysis of the archaeological collection of Pampa Grande (Salta, Argentina), Antí Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 37: 95-118.

- Moreno E (2019) Approach to Candelaria ontology: the iconography of the bat as a case study. Degree thesis to opt for the title of archaeologist, unpublished. Faculty of Natural Sciences and Miguel Lillo Institute, National University of Tucumán, Tucumán, Argentina.

- Alberti B (2012) Cut, pinch and pierce. Image as practice among the early formative La Candelaria, First Millennium AD, Northwest Argentina. Encountering Imagery Materialities, Perceptions, Relations. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 57: 13-28.

- Alberti B, Marshall Y (2009) Animating archaeology: local theories and conceptually open-ended methodologies. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19(3): 344-356.

- Moreno EA, Mollerach M, Caria MA (2019a) Approach to Candelaria ontology: faunal representations in the NOA lowlands, in A. Laguens, M. Bonnin, B. Marconetto (Comps.), Book of abstracts XX National Congress of Argentine Archeology. Cordoba Argentina p 1563-1568.

- Moreno EA, Mollerach M, Caria MA (2019b) The human and non-human in the worldview of the pre-Hispanic groups of the NOA lowlands." Lillo, Education, Science and Transfer. Monographic and Didactic Series No. 5. XIV Internal Conference on Communications in Research, Teaching and Extension. Faculty of Natural Sciences and Miguel Lillo Institute. National University of Tucumán p. 49.

- Alberti B (2016) Archaeologies of Ontology. Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 163-179.

- Latcham RE (1928) Chilean indigenous pottery. Universe Printing-Lithography Society, Santiago de Chile.

- Moreno EA (2017) Approach to Candelaria ontology: the iconography of the bat as a case study. Lillo, Education, Science and Transfer. Monographic and Didactic Series No. 1. Minutes XIII Communications and V Interinstitutional Conferences. Faculty of Natural Sciences and Miguel Lillo Institute (UNT), Miguel Lillo Foundation (UNT). Tucumán, Argentina 54.

- Moreno EA, Caria MA (2018) Slain vessels in the American regional context: a proposal for analysis. Lillo, Education, Science and Transfer. Monographic and Didactic Series No. 5. XIV Internal Conference on Communications in Research, Teaching and Extension. Faculty of Natural Sciences and Miguel Lillo Institute, National University of Tucumán p. 50.

- Núñez L, Cartajena I, López P, Carrasco C, Valenzuela M, et al. (2019) Nichos, cámaras y ceremonias en el templete Tulán-54 (Circumpuna de Atacama, Chile). Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines 48(1): 57-81.

- Pérez Ares MA (1972) The burial of infants in urns: findings in the province of Córdoba, Anales de Arqueología y Etnología 27: 81-90.

- Zárate P (2019) Of life and death in the mountains of Córdoba (2500-400 years BP): Interpretations from Social Bioarchaeology, Degree Thesis, National University of Córdoba, Có