Decolonising Cultural Heritage in an Independent Scotland

Lynda Baird-Naysmith*

University of the Highlands & Islands, Scotland

Submission: May 14, 2023; Published: May 22, 2023

*Corresponding author: Lynda Baird-Naysmith, University of the Highlands & Islands, Scotland, Email id: orkneylodge@aol.co.uk

How to cite this article: Lynda B-N. Decolonising Cultural Heritage in an Independent Scotland. Ann Rev Resear. 2023; 9(2): 555756. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2023.09.555756

Abstract

Cultural heritage theory emphasises the importance of values and significance when considering monuments. Based on an existing heritage values typology, this research provides an appraisal of values and significance for selected monuments, also from the standpoint of different stakeholders. The analysis includes discussion of tensions between memory and forgetting in representation and commemoration, also taking into account postcolonial theory relating to values based on perspectives of different stakeholder groups in a colonial society. Here, self-determination independence of ‘a people’ as also being about decolonisation is considered in the context of a future independent Scotland. The research investigates cultural heritage literature and postcolonial theory and applies these areas of thought to provide for case study analyses regarding selected monuments in the context of a contested cultural environment (i.e., Scotland). The research then extends further by applying cultural heritage values/significance typology via a questionnaire survey undertaken at selected monuments.

Keywords: Decolonisation; Typology; Black Lives Matter; The Great Tyrant

Introduction

Historically, statues have been toppled and removed in many countries around the world, particularly in instances where Imperialism and colonialism occurred Dirks [1], and/or where former despotic governing regimes were removed. In this regard a peoples’ understanding, and appreciation of history may change over time, though they may also be prone to ‘forgetting’, especially in circumstances where narratives of conservative authorities reflect bias and self-interest of dominant elites and cultures holding power. Decolonisation is about much more than the return of plundered artefacts to their origin Hicks [2], being primarily about the expression of “national consciousness which is the most elaborate form of culture” Fanon [3]. During recent times, statues have been toppled in the wake of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, referred to as ‘Fallism’. According to Ahmed [4] the idea of Fallism first emerged at the end of 2015 in South Africa. In the case of the Colston statue in Bristol (Colston was a slave trader), which was torn down by protestors and thrown into a dock in 2020, it was argued by the defense in the subsequent court case that ‘defendants were on the right side of history’ Gayle [5]. Similarly, the United Nations calls on member states to be ‘on the right side of history’ in respecting the right of peoples to self-determination independence, also regarded as decolonization United Nations [6]. Fundamental changes in the socio-political environment over time may therefore lead to calls to deal with what is viewed as a colonial cultural heritage legacy Whelan [7].

In this research, it is suggested that the prospect of Scottish independence as an aim of the present devolved Scottish Government Scottish Government [8] represents a fundamental change in environmental circumstance. Moreover, what does independence mean, if anything, for Scotland’s cultural heritage, much of which appears to incorporate something of an Imperial legacy over the last three centuries of a union which some have argued was colonial in purpose and effect Hechter [9]; Baird [10]? It is also recognised that the term oppression has shifted from meaning the exercise of tyranny by a ruling group to signifying the injustice some suffer due to the everyday practices and norms of a society Prilleltensky and Gornick [11]. Continuing the general theme and desire for independence among a sizeable proportion of Scots, the current Scottish Government has committed to holding a further referendum, failing which a plebiscite on independence may be held at the next UK or Holyrood General Election.

Cultural heritage theory emphasises the importance of values and significance when considering monuments, a key factor here being ‘whose’ values are deemed significant and are thus prioritised? Based on existing heritage values typology Fredheim and Khalaf [12], this research aims to provide an appraisal of values and significance for selected monuments, also from the standpoint of different stakeholders. The analysis includes discussion of tensions between memory and forgetting in representation and commemoration, also taking into account postcolonial aspects relating to values based on perspectives of different stakeholder groups. Here, the UN definition of selfdetermination independence of ‘a people’ as also being about decolonisation United Nations [6] is considered in the context of a potential independent Scotland.

Monuments selected for analysis are

The Duke of Sutherland statue in Golspie in the Scottish Highlands, the Duke of Wellington statue in Royal Exchange Square, Queen Street, Glasgow, and Lord Melville’s monument in St. Andrews Square, Edinburgh. It is hypothesized that these statues/monuments could be considered as controversial and contested monuments, also with regard to a post-union/postcolonial independent Scotland. In this sense they may be regarded much as similar statues were in a liberated Ireland Whelan [7] and in numerous other former colonies Memmi [13] which, postindependence, considered many of its monuments etc. to be a legacy of Imperial oppression. The research assesses cultural heritage literature and postcolonial theory and applies both areas of thought to provide for case study analyses regarding selected monuments. The research then extends further by applying cultural heritage values/significance typology Fredheim and Khalaf [12] via a questionnaire survey undertaken at the selected monuments.

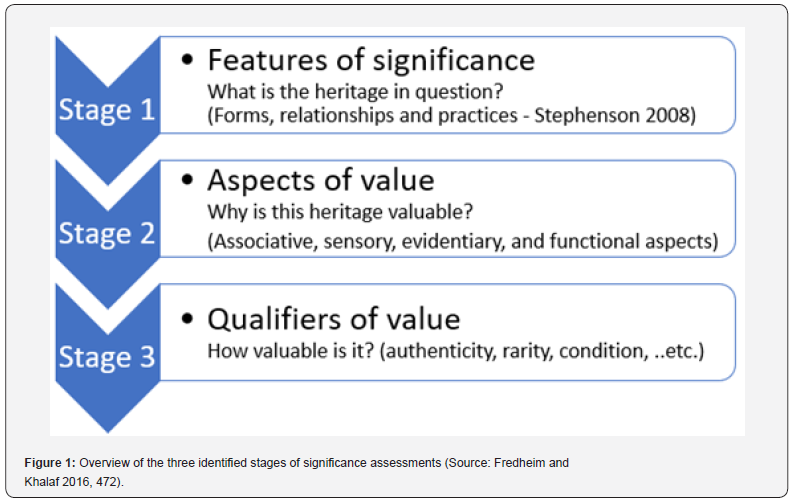

Cultural Heritage

History is full of examples of Fallism where those commemorated by monuments and other means are subsequently viewed as oppressors and tyrants. Perceptions and understanding change over time and are subject to events. The present Scottish Government is committed to holding another referendum on independence and/or a plebiscite election on independence by 2024/25. It is therefore possible that Scotland could revert to becoming an independent country again within a relatively short period. This is the context, though not the subject of this study. The issue of re-evaluating the place of monuments isn’t necessarily going away if independence is rejected. And, even if Scotland does become independent it isn’t clear that its heritage best interests would be well served by removing all Imperial monuments. What does seem important, however, is that Scotland’s heritage is better understood. Heritage theory emphasises values and significance (Figure 1) when evaluating monuments Fredheim and Khalaf [12], albeit views differ from the standpoint of different stakeholders, elites and cultures. Memory and forgetting in representation and misrepresentation and commemoration also plays its part. In the colonial environment, native history and culture tends to be intentionally diminished, obliterated even, and it is primarily the values of the coloniser which are sovereign Memmi [13].

Monumental legacies don’t need to be permanent features as Riegl [14] thought during what may have been the modern Imperial pinnacle period over a century ago. Cultural obliteration (i.e., destruction of native culture), which is an aim of colonialism, tends to leave a legacy of symbols and monuments commemorating ‘superior’ oppressor elites Fanon [3]. Oppression of native cultures is a feature in this process, resulting in different narratives and versions of the past being presented Harrison and Hughes [15]. Here there is a need to consider and apply decolonial thinking to understanding cultural heritage Knudsen [16] in the context of Scotland’s possible independence and decolonization. Conservative authorities invariably seek to defend Imperial/ colonial structures and narratives Mignolo and Walsh [17], or even to deny oppression Hicks [2], and tend to avoid discussion or understanding of legacy heritage resulting from oppressive exploitative regimes Barassi [18]. The range of values attached to heritage requires mainly an anthropological perspective Mason [19], yet a difficulty arises in the Scottish context because perceptions of colonialism (still) tend to be obscured. Consequently, a person seeking independence may often have only a rudimentary understanding of the true extent of their ‘wretchedness’ Fanon [3].

This creates a need for thoughtful reinterpretation’ to allow for ‘deeper understanding’, in turn ‘adding new layers of meaning’ Historic England [20]. Removing heritage is also about clearing the way for a new collective memory Benton [21], reflecting improved understanding of the cultural context. Institutions current focus on ‘decolonization’ relates to perspectives of classical colonialism and slavery including the BLM (Black Lives Matter) movement. However, Imperial and colonial oppressions were also levelled against white ethnic groups in Europe, including the Scots, Irish, and Welsh, each (still) subjected to Anglocentric Imperial cultural superiority and oppressive policies Hechter [9] and not dissimilar to Asian and African colonies (Said 1994, 287).

Colonial Monuments

An oppressed people rightly question if they should have to walk past symbols of oppression and inequality every day, such as monuments left by an Imperial power. Whether such statues are ‘educational’ or not in the colonial environment is another matter, and here it is usually dominant elites who hold the narrative and values of the colonizer sovereign Memmi [13] in what remains an elite ‘infrastructure of colonialism’ directed at subordinate conquered indigenous groups. Historic dispossessions emptied much of Scotland of its indigenous people, obliterating their culture and language; this brings us into the realms of ethnic cleansing, and genocide Hunter [22] and, in terms of ‘cultural genocide’ the process may not have ended Grouse Beater [23]. Ecological Imperialism’ further implies that Imperial elites also sought “to change the local habitat” Crosby [24], replacing people with sheep being an example, and various other schemes (e.g. SSSI’s; Highly Protected Marine Areas etc.) which constrain local economic development potential. Thus, everything that belongs to the colonizer is not appropriate for the colonized” Memmi [13], including it might be added his grand monuments and dubious values.

Cultural Imperialism results in an alien culture, language and cultural hegemony (and its values) being imposed on a people Buttigieg [25]. In such a colonially manufactured environment, an oppressed people may develop a ‘colonial mindset’ which leads to their own denial and/or downplaying the reality of discrimination or any past history of racism. The dominant coloniser is thus “custodian of the values of civilization and history” forcing the colonized to accept his (alien) values and his monuments of self-glorification Memmi [13]. Colonial exploitation is always a co-operative venture aided by native elites, whereby the latter become “part of the group of colonizers whose values are sovereign” Memmi [13]. Under Imperial rule it is only ever the ‘mother country’ which exudes “positive values” Memmi [13]; this is clearly an important factor in considering the development and significance of monuments and other symbols in a contested territory where such monuments may only be accepted by the more assimilated native.

Heritage Values and Significance

In seeking to preserve heritage, it is important to consider “the meanings and values attached to objects (that) provide the very reason for conservation” Pye [26]. A key task here lies in identifying the ‘values’ which constitute the significance of heritage. Significance in this sense is understood as the overall value of heritage or “the sum of its constituent ‘heritage values’” Fredheim and Khalaf [12]. Identity at the national level is considered to be the most important factor here, which, in this instance, reflects aspects of value and significance in the context of those holding to a British identity Howard [27] as opposed to a Scottish identity Bond [28]. It is considered that values-based approaches may fail where “decisions are based on incomplete understandings of heritage and its values” Fredheim and Khalaf [12]. Different people will inevitably hold different views about heritage values, depending on their culture, identity, and values. Identities and cultures come into play because national identity and national consciousness is itself a cultural emotion heavily influenced by national culture and indigenous language, as well as by cultural assimilation policies Fanon [3]; Baird [10]; Memmi [13].

People from different social backgrounds, traditions, professions, and cultures therefore tend to express different values Pearson and Sullivan [29]. Heritage values may be rather subjective with, usually, a “tension between institutional or ‘official’ values, and the values people produce” Ireland, Brown and Schofield [30]. There are also differences in assessing ‘value’ Fredheim and Khalaf [12]. Critical in this regard are features that make the heritage significant; what aspects are of value, and what are the qualifiers of value allowing value determination assessing its ‘value’ Fredheim and Khalaf [12]. The term cultural significance is closely associated with The Burra Charter Australia [31]. Significance also relates to the particular ‘nation’ of people from which values are constituted and measured Tainter and Lucas [32], hence the term ‘national heritage’. In the colonial context, there is clearly going to be a difference in what is meant by ‘national heritage’ as opposed to the heritage of other nations and peoples, including the heritage and values of another dominant nation that may have been imposed on a people. In a colonial environment the legacy of capitalist and colonialist perspectives as defined by the dominant culture and settler groups obscure this reality. Marginalized and oppressed (native?) groups tend to be excluded from heritage decisions, with dominant groups including authorities reflecting and projecting only the dominant culture making most of the decisions Baird [10]. This necessitates greater emphasis on adopting inclusive values typologies Ireland [33] or, in the case of decolonization, taking a completely fresh approach prioritising native national identity, culture and values.

Individuals Commemorated

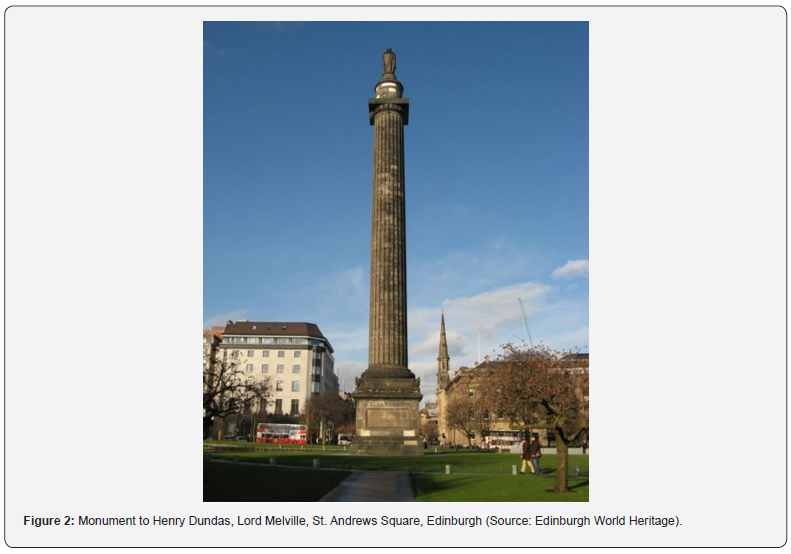

This research investigates the decolonisation of cultural heritage within a Scottish context also with emphasis on a possible post-UK union reality and an independent (i.e., postcolonial) Scotland. In this scenario certain monuments may be viewed as a legacy of colonialism. A questionnaire developed from the Fredheim and Khalaf [12] values/significance typology is applied to three monuments selected as exploratory case studies. Each monument is already considered contestable in regard to Scotland’s history and heritage. The Lord Melville monument in Edinburgh (Figure 2) commemorates Henry Dundas who, as Lord Advocate, basically ran Scotland on behalf of the British state during the period following shortly after the war of independence (or ‘rebellion’) of 1745/46. Known as ‘The Great Tyrant’, evidence suggests Dundas’ main role was to ensure that Scotland and the Scots were kept in line with British Empire objectives; the main function of Scotland (as with Ireland and Wales) being to provide a resource (food, goods and people) for the British Empire’s sustenance and corporate-military expansion Hechter [9]. Whilst this may have been positive for Scotland’s tiny elite and mostly Anglicised governing class, many of whom were by now based in London most of the time and therefore absent from Scotland, it was rather less than advantageous for the mass of Scots or the further development of the Scottish nation. Dundas, who was also Minister for War and Colonies, is therefore commemorated by a British Imperial power for his contribution to furthering Imperial domination (at home and abroad), and for acting more or less as Scotland’s ‘Governor General’ overseeing and subjugating what was and remains even today a restive ‘internal colony’ Hechter [9].

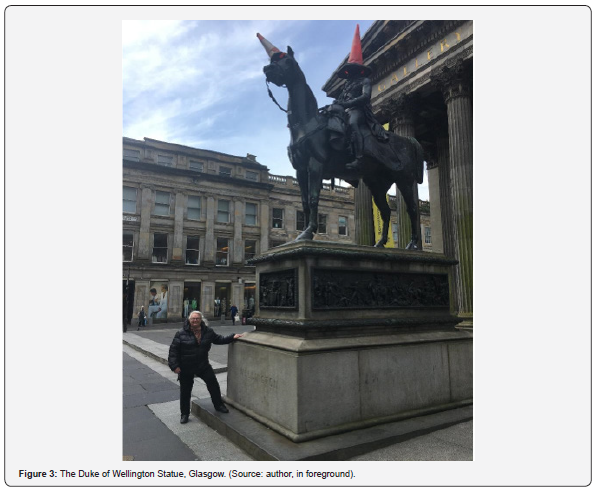

The Duke of Wellington statue in Glasgow (Figure 3) commemorates Arthur Wellesley who was born into an Anglo-Irish aristocratic family. Wellesley combined a long political and military career. He returned from India with a fortune in ‘prize money’ after leading numerous military campaigns which effectively destroyed native peoples and cultures enabling their economic exploitation and the plunder of India by voracious British corporate interests. Wellesley was basically therefore a corporate mercenary leader, another part of Britain’s extensive global ‘militarist-corporate colonialism’ Hicks [2]. Such an elite were automatically in receipt of titles and privileged positions including being given senior roles in British governments. Wellesley’s connections with Glasgow or indeed with Scotland appear non-existent, though his statue there may reflect a desire by local elites to align with and project British Imperial superiority and power from which such elites were also prospering and co-opted to maintain.

The Duke of Sutherland monument in Golspie (Figure 4) commemorates George Levesen-Gower, 2nd Marquess of Stafford who married the Countess of Sutherland. Leveson-Gower was also an MP and British Ambassador to France during the French Revolution. The county of Sutherland and other parts of Scotland were cleared of thousands of indigenous native Scots families by Leveson-Gower and other landowners. This followed the earlier removal of people and forfeiture of lands owned by Jacobite ‘sympathisers’ by British government forces. Removal of Scots from Scotland was subsequently further achieved through British government legislation such as Empire Resettlement Acts. Legislation and policies were therefore employed by successive British governments to remove Scots from their homeland and to obliterate their culture; this is precisely the aim of Cultural Imperialism Phillipson [34] and colonialism, which is at root racism Memmi [13]. The Leveson-Gower statue does not therefore appear to commemorate anything other than Imperial oppression and barbarity inflicted by a tyrannical elite on a ‘subordinated’ ethnic indigenous group (i.e., the Scots).

Survey Findings

Most survey respondents (questioned when visiting the monuments) had little idea of who the LM (Lord Melville) monument commemorated, whilst some said they knew who the DS (Duke of Sutherland) and DW (Duke of Wellington) monuments commemorated. Relatively few people seemed to know what any of the monuments actually commemorated. Few respondents regarded the monuments as architecturally significant; this differed markedly from opinions of official heritage bodies, especially in regard to the ‘grander’ LM monument. The DS monument is associated with barbaric Highland clearances of indigenous Scottish people, and therefore is considered to commemorate a tyrant. The DW monument is viewed locally and by visitors as primarily an iconic feature of Glaswegian humour due to traffic cones being permanently positioned on the statue and permitted by authorities. The LM monument is to a large extent merely viewed as a high pillar with an obscure unknown figure atop. None of the statues were valued at all by any of the respondents.

Most respondents considered the LM and DW monuments as irreplaceable, though the majority were unable to explain why they were deemed as such. A paradoxical perspective suggested the LM monument should not be preserved. A large majority suggested the DS monument should be removed, or alternatively replaced with a statue commemorating the oppressed people who suffered at the hands of DS. None of those commemorated were considered to have significance for the city or local area concerned, or for Scotland.

Heritage professionals interviewed were similarly unaware specifically why the monuments commemorated the respective individuals, their focus seemed more concerned with who pays for preservation. Emphasis was placed on ‘architectural significance’ and a need for ‘understanding’ of the past which the presence of these monuments was assumed to facilitate. However, this seemed to downplay or even ignore the barbaric and questionable record of those commemorated, which appears more to do with celebrating a despotic privileged elite class and its dubious values reflective of an alien culture and foreign rule dominating for the most part an oppressed and exploited Scottish people.

Implications for Future Research and Policy

There will be those who seek to frame this debate in terms of national identity and political self-determination, and those who prefer to maintain a prevailing dominant (i.e., ‘unionist’ or colonial) narrative, each also reflecting to some extent different cultures and values as well as the psychological influence of cultural assimilation Cesaire [35]. Nevertheless, a re-evaluation of cultural significance (and history) based on group inequality and identity rebalancing might be expected, especially in a fundamentally changing political and ‘national’ landscape. It is argued that this research has implications for Scotland, for the UK, and internationally for other peoples in self-determination conflict. Material culture is seldom a simple matter of black and white. As Scotland perhaps moves closer to returning to again become an independent state, the people will inevitably wish to revisit their culture, history and heritage in this vein. Are many of the individuals commemorated by monuments across Scotland celebrating Scottish national culture, or do they merely reflect the stern gaze of an oppressor who keeps a dominated people and culture in its subordinate place?

Inevitably there will be implications for cultural heritage policy and management in any newly independent country. New institutions will need to be created, reflecting the ideals and priorities, as well as the culture, language and values of a liberated people, rather than those of a dominating oppressor. Such aspects will undoubtedly influence national policy and practice if, or when, Scotland becomes independent again. Independence is itself considered a fight ‘for a national culture’ Fanon [3] and, upon liberation, a colonial heritage legacy may rightly be viewed as commemoration of the culture and power of a dominating and unwelcome oppressor. It may be that the best interests of Scotland are not served by removing all Imperial monuments, and place names etc. In spite of some superficial similarities from the survey, consensus appears to be that the Lord Melville and Duke of Wellington monuments could be retained, while that of the Duke of Sutherland should be removed or replaced by something to commemorate those who were oppressed; the understanding of ‘a peoples’ oppression may nevertheless remain rudimentary when obscured by an intense and prolonged cultural/colonial assimilation process. However, choices have to be made as it may not be possible to keep everything. Statues tend to be a special case because they not only represent events and society at a particular time but were created to honour particular individuals. To leave such monuments unmodified is to endorse their ideology and often questionable ‘achievements’, especially for an oppressed people seeking and then securing liberation.

Conclusions

Perceptions of what is or is not acceptable in any society change over time. We now see a renewed push for Scottish independence after Scotland’s enforced withdrawal from the EU, and repeated electoral mandates for another referendum ignored by UK governments. There is consequently increasing awareness of Scotland’s rather powerless colonial status and related political, economic and cultural domination. Fundamental political change of the magnitude of independence implies that a quite different perspective may arise regarding what is meant by ‘national’ cultural heritage in Scotland, reflecting Frantz Fanon’s view that independence is ‘a fight for a national culture’. Riegl’s [14] ‘Modern Cult of Monuments’ emphasised the role of Imperial/ colonial rule by another (i.e. alien) dominant people and culture. The importance of ’culture’ in determining significance of heritage influencing values assessments is self-evident. Accumulation of heritage and collective memory is also influenced by a people forgetting its past, aided by dubious oppressor narratives in the colonial setting, the latter’s values reinforcing a dominant culture, as well as its myths. In the colonial situation, archaeological practice has also often been carried on by people with no historical or cultural ties with the peoples who’s past they were studying Trigger [36]; only around ten per cent of the academics in Scotland’s elite universities today are Scots Baird [10], which helps explain the lack of academic or institutional interest or support for Scottish culture never mind independence. Decolonisation allows for and necessitates a people’s cultural self-recovery Memmi [13] which is essential in order to repair the cultural obliteration and severe long-term damage suffered by institutionally oppressed groups lacking opportunity in their own land. Removing heritage is also about clearing the way for a new collective memory Benton [21], reflecting improved understanding of the cultural context.

Imperial/colonial statues inevitably generate “incredible scorn for the colonized who pass them by every day”, celebrating only the oppressive deeds of colonisation Memmi [13]. The “crushing of the colonized” is included among the colonizer’s values Memmi [13] and his monuments reflect this crushing. A newly independent people therefore have to grapple with the effects of this, and with what is and would otherwise remain a colonial cultural heritage legacy. Public perception of the statues investigated, which are clearly of an Imperial celebratory nature, seems limited. Values and significance relating to such monuments tend to be obscured by dominant prevailing narratives, hence understanding even by an oppressed group remains rudimentary. This to some extent leaves the way clear for an authorised heritage discourse to hold sway, the latter reflecting the dominant imposed culture, which is clearly not the same as indigenous (i.e. oppressed) group culture. Survey responses reflect this to some extent in that respondents had little idea of who the LM statue commemorated, or the DW statue, the latter better known for the mere fact of a traffic cone placed on the statue as a permanent feature. More was known about the DS statue, with most people wanting some action taken, though paradoxically some local people also held emotional attachment to the monument as a reminder of past atrocities.

Identity at the national level is considered most important as therein lies the power of Imperialism to impose another (national) identity on a people, officially as well as culturally, and with that comes the adoption of dominant values (of the coloniser) due to cultural assimilation Hechter [9]; Memmi [13]. National identity is a cultural emotion determined by national culture and indigenous language, both of which are severely damaged and significantly altered through the oppressive colonial ‘cultural assimilation’ process Fanon [3]; Memmi [13]. Significance further relates to the ‘nation’ and identity from which values are constituted and measured Tainter and Lucas [32], hence the term ‘national heritage’. In any decolonisation situation the idea of the ‘nation’ inevitably alters. The Burra Charter’s importance lies in the shift from ‘monuments’ to ‘places of cultural significance’; that is, from the perspective of an indigenous people and nation Ireland, Brown & Schofield [33].

Emphasizing broader political shifts, Imperial statues remain questionable ‘lumped’ as they often are onto another people and culture, inevitably coming to be viewed in a different light as the shift from subordinate colonial territory to post-colonial independent state transpires Whelan [7]. In such circumstances, a liberated people rightly wonder about their Imperial monumental legacies and the dubious ‘values and individuals attached to them. In Scotland’s case, this further relates to a mostly Anglicised gentry and Anglophone meritocratic elite and professional/ managerial class reflecting an elevated and privileged cultural and socio-economic position relative to speakers of the indigenous native (Scots) mither tongue, the latter neither taught nor given statutory authority. This results in a ‘cultural division of labour’ and institutionalised socio-linguistic prejudice perpetuating societal control by a dominant, though alien, ‘cultural hegemony’ Kay [37]; Hechter [9]; Baird [10].

In summary, it therefore remains questionable if any of the three monuments considered in this study actually represent what might be termed Scottish ‘national’ cultural heritage at all. Conversely, it may reasonably be proposed that they commemorate only an oppressive British governing elite and its dubious ‘values’. This finding is important to consider in the context of Scotland becoming an independent country again, at which time the people may be expected to seriously review what passes for their ‘national’ cultural heritage, and what may be perceived as a colonial and hence oppressive legacy.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Simon Clarke of UHI and Professor Alfred Baird for their expert advice, suggestions and guidance in this research.

References

- Dirks NB (1992) Introduction: colonialism and culture’ in Colonialism and Culture, ed. by Dirks, N. B. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press p: 1-26.

- Hicks D (2020) The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. London: Pluto Press.

- Fanon F (1970) The Wretched of the Earth. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin (First published in France by Francois Maspero editeur 1961).

- Ahmed AK (2020) Towards an Emergent Theory of Fallism (and the Fall of the White-Liberal-University in South Africa) in A Better Future - The Role of Higher Education for Displaced and Marginalised People (ed) Bhabha J, Giles, Mahomed F Cambridge: Cambridge University Press pp. 339-362.

- Gayle D (2022) Jury in Colston statue trial urged to ‘be on the right side of history.

- United Nations (2022) United Nations and Decolonization: A brief historical overview.

- Whelan Y (2002) The construction and destruction of a colonial landscape: monuments to British monarchs in Dublin before and after independence. Journal of Historical Geography 28(4): 508-533.

- Scottish Government (2022) (Renewing democracy through independence - gov.scot (www.gov.scot).

- Hechter M (2017) Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Baird A (2020) Doun-Hauden: The Socio-Political Determinants of Scottish Independence. Kindle Direct Publishing.

- Prilleltensky I, Gornick L (1996) Polities change, oppression remains: on the psychology and politics of oppression. Political Psychology 17(1): 127-148.

- Fredheim LH, Khalaf M (2016) The significance of values: value typologies re-examined. International Journal of Heritage Studies 22(6): 466-481.

- Memmi A (2021) The Colonizer and the Colonized. London: Profile Books.

- Riegl A (1903) Der moderne Denkmalkultus, seine Wesen und seine Entstehung, Vienna, 1903 (English translation: Forster and Ghirardo, ‘The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origins’, in Oppositions p. 21-51.

- Harrison R, Hughes L (2010) Heritage, colonialism and post colonialism in Understanding the politics of heritage ed. by Harrison, R. Manchester: Manchester University Press pp. 234-269.

- Knudsen BT, Oldfield J, Buettner E, Zabunyan E (2022) Decolonizing Colonial Heritage: New Agendas, Actors and Practices in and Beyond Europe. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Mignolo WD, Walsh C (2018) On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics and Praxis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Barassi S (2007) The Modern Cult of Replicas: A Rieglian Analysis of Values in Replication. Tate Papers No. 8. Autumn.

- Mason R (2002) Assessing Values in Conservation Planning: Methodological Issues and Choices’ in Assessing the Values of Cultural Heritage ed. by de la Torre, M. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute.

- Historic England (2021) Contested Heritage.

- Benton T (2010) Heritage and Changes of Regime’ in Understanding Heritage and Memory ed. by Benton, T. Manchester: Manchester University Press pp. 126-163.

- Hunter J (1976) The Making of the Crofting Community. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd

- Grouse Beater (2021) The Blight of Second Homes.

- Crosby A (1986) Ecological Imperialism: The Bilogical Expansion of Europe, 900-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buttigieg JA (1992) Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pye E (2001) Caring for the past: Issues in Conservation for Archaeology and Museums. London: James & James.

- Howard P (2003) Heritage, Management, Interpretation, Identity. London: Continuum.

- Bond R (2014) National identities and the 2014 independence referendum in Scotland. Sociological Research Online 20(4): 92-104.

- Pearson M, Sullivan S (1995) Looking after Heritage Places: The Basics of Heritage Planning for Managers, Landowners and Administrators. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Ireland T, Brown S, Schofield J (2020) Introduction: (in)significance – values and valuing in heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies 26(9): 823-825.

- Australia ICOMOS (2013) The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance.

- Tainter JA, Lucas JG (1983) Epistemology of the Significance Concept. American Antiquity 48(4): 707-719.

- Ireland T, Brown S, Schofield J (2020a) Situating (in)significance. International Journal of Heritage Studies 26 (9): 826-844.

- Phillipson R (1992) Linguistic imperialism and linguicism. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Cesaire A (2000) Discource on Colonialism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Trigger BG (1984) Alternative Archaeologies: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist. Man, New Series 19(3): 355-370.

- Kay B (2006) Scots: The Mither Tongue. Edinburgh: Mainstream.