Identifying the Glaze Pigments in the Achaemenid Glazed Bricks of Apadana palace in Susa by Inductively Coupled plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy Method (ICP- OES)

Soodabeh Yousefnejad*

Assistant Professor, Islamic Azad University, Central Branch of Tehran, Iran

Submission: February 21, 2023; Published: March 01, 2023

*Corresponding author: Soodabeh Yousefnejad, Assistant Professor, Islamic Azad University, Central Branch of Tehran, Iran

How to cite this article: Soodabeh Yousefnejad. Identifying the Glaze Pigments in the Achaemenid Glazed Bricks of Apadana palace in Susa by Inductively Coupled plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy Method (ICP- OES). Ann Rev Resear. 2023; 8(4): 555749. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2023.08.555749

Abstract

In this paper, the chromatic glazes of blue, yellow and white from the Achaemenid glazed bricks of Apadana Palace in Susa have been studied by the ICP quantitative analysis of inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy. The objective is to identify the quantity of colorant transition elements in the Achaemenid chromatic glazes and studying the similarities and differences in their elemental composition in making different chromatic shades, especially blue and green-blue colors. For identifying the colorant transition elements of the glaze, the quantitative analysis method ICP-OES has been used, because of which the quantity of thirty-six elements, including copper, lead, antimony etc. also alkali and alkaline earth elements in each of the chromatic glazed of the studied samples has been found out. Results from quantitative analysis of elements report a significant percentage of cobalt and copper in the blue samples; in the turquoise, copper and a significant amount of lead and antimony; in the yellow sample antimony and lead, and in the white sample calcium and antimony. There is a considerable difference between the amount of alkali elements in the turquoise sample that is green blueish in compare with the blue samples, and the presence of lead and antimony which demonstrates the yellow lead antimonite which, alongside with copper ion has resulted in green blue in the turquoise blue glaze.

Keywords: Glazed brick; Achaemenid; Susa; Apadana palace; Instrumental analysis; ICP-OES

Keywords: ICP-OES: Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectroscopy; SEM-EDS: Scanning Electron Microscopy- Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy; XRD: X-ray powder diffraction

Introduction

The use of glazed bricks for the decoration of buildings is traced back to ancient Mesopotamian. Sumerians and Akkadian have created glazed decorations in the first half of the 3rd millennium B.C. Babylonian and Assyrian art inherited this tradition afterwards. They used glazed bricks in the exterior decorations of their palaces and temples. Koldewey has found in his Babylonian excavations a huge mass of glazed bricks, by assembling of which he could reconstruct the colored brick gates that are currently kept at Berlin Museum Moortgat [1]. This tradition made its way into Iran in the 2nd millennium B.C. during the Elamite period. A huge mass of glazed bricks and decorations had been used in the most prominent building left from their dynasty, i.e., Choqa Zanbil, in Susa Grishman [2]. Later, Achaemenid kings like Darius constructed his palace in Susa, adapted many Elamite elements and ornamentations Briant [3]. Glazed bricks in different colors such as white, yellow, blue, and turquoise blue were used widely for decorating the walls with figurative motifs of soldiers and geometric patterns and plant motifs as well as mythical animal figures. The decorative motifs on these bricks are separated with dark braces Caubert [4], Harper [5].

In this study, the samples were extracted from chromatic glazes of these bricks belonging to Apadana Palace being kept at Susa Museum and Iran’s National Museum and are studied and analyzed to identify their colorant transitional elements. The chromatic glazes of the studied bricks are in white, yellow, blue, and turquoise blue, and their elements are quantitatively analyzed to determine the transition pigment elements of the chromatic glazes and also studying the similarities and differences between their compositions, especially in making two different colors of blue and green. Historically, the chromium ion is the basis of most of the green pigments. The green-blue pigments also resulted from the compounds of cobalt and chromium. Using a more amount of chromium oxide and less amount of cobalt oxide would result in greener pigments. Besides, by decreasing the amount of chromium oxide and increasing the amount of cobalt oxide, blue green to blue pigments would come out. Copper compositions are also used to make green pigments, and this element is of great significance in art, due to the very delicate colors it would result in Eppler [6]. Thus, the samples in this study are examined for determining the quantity of pigment elements of white, yellow, blue, and turquoise blue glazes, and studying the similarities and differences of their elemental compositions and especially regarding the mentioned notions on the make of green-blue color and recognizing the elements that make two different colors of blue and green blue in the blue and turquoise samples. For this purpose, the inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy quantitative element analysis method which was introduced in 1964 and is capable to identify the quantity of elements and even those at very small amounts without any chemical interfere, is used Wang Zhao [7].

Background

Numerous studies have been done on ancient ceramics with different instrumental chemistry and micro-analysis from twenty years ago and with the purpose of identifying the chemical characteristics of the glaze, studying the deterioration processes, and carrying out mineralogical and chemical studies of the glazed ceramics and non-glazed ones. There follows a review of studies carried out during the last several years which have used the same method for analyzing ancient ceramics, and some studies on Susa’s glazed bricks to identify their composition as well as their technical aspects. Anne Caubet and her coworkers have studied some pieces of Achaemenid glazed bricks from Darius’s Palace which they have found in their archeological excavations during 1884-86 to identify their structural qualities. They have used XRF method and found out that the bodies included Silicon structures with a low amount of Al2O3 and Fe2O3, and the chromatic glazes included the same compositions of Mesopotamian and Egyptian samples. They have noted the presence of chromatic oxides such as copper in these glazes Caubet [4]. Marion Yung and coworkers, too, have studied eight samples of the glazed bricks of Susa including black, yellow, brown, dark, and light blue, and turquoise with XRD method. The results from their analysis of the body and glaze structures showed that the bodies include silicone, and the black glaze includes manganese and iron oxide, the yellow samples include lead and antimony compounds, the white samples include sodium and antimony compounds, the turquoise samples include copper and lead compounds, and blue samples include copper and cobalt compounds. They have noted the presence of the rare element of cobalt and its excavation from Iran’s mines in that age Jung [8]. Mike Tite and his coworkers have also studied four samples of Achaemenid glazed bricks of Darius’s palace in Susa with SEM-EDS method. Regarding their results, the bodies are made of silicone. They consider the sandy structure of these bricks than the clay bodies of past ages as technical progress. He introduces the colors of the blue and yellow glazed bricks to be derived from copper and the compounds of lead and antimony Tite [9].

Later, Lahill and his team of coworkers studied several samples of Susa’s glazed ceramics. They have analyzed the bodies with PIXE and have identified a clay structure including carbonate and compounds of iron and magnesium with sands in all the ceramic bodies, and iron and silicone oxides, and sources of aluminum oxide and potassium hydroxide (Lahill, et al., 2009).

Maggetti and his coworkers have done a semi-quantitative analysis on ancient chromatic glazes of yellow, green, turquoise, and brown with SEM-EDS method. They have identified the structural compositions of the chromatic glazes and colorant transitional elements in these examples and have introduced antimony compounds as the glaze opacifier in the studied ancient samples Maggetti [10]. Holakooie, too, has studied several samples of Neo-Elamite Susa belonging to Acropolis with thermal analysis, XRD, SEM-EDS and micro-Raman methods, and as results have reported the presence of copper compounds in the blue and green samples, calcium antimonate in the white samples, lead antimonate in the yellow and green ones as the glaze opacifier pigment. He considers the heating temperature of these ceramics below 900 degrees centigrade Holakooei [11]. Also, in a study which has used different instrumental analysis methods for examining the technical features of the Achaemenid glazed bricks found in archeological excavations of Tall-e-Ajori in the city of Parse, has used inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy method for identifying the color of the glazed bricks which have been faded into white due to the deterioration caused by the burial environment. According to the reports of this study, these ancient samples include considerable amounts of copper and cobalt elements in the blue samples, and lead and antimony in the yellow lead antimonate pigment Yousefnejad [12].

Sampling, Testing Methods, and Instruments

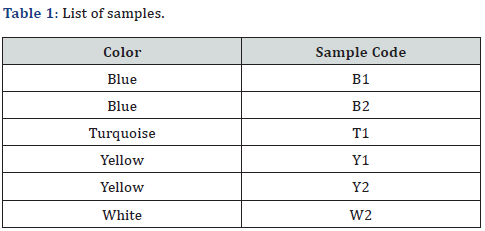

The studied samples in this test include five samples of the glazed bricks in white, yellow, blue, and turquoise belonging to Apadana palace of Susa kept at Susa Museum and Iran National Museum, Sampling process was done with the corporation of the experts of Iran National Museum and Susa Museum. The glaze samples of this study are studied with optical microscope for a close observance of the color of the glazed layer and their surface quality, and for the quantitative identification of the element, samples are analyzed and studied by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy method. The devices used in this study include optical/light microscope (JENUS) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy device (model Agilent radial 735, made in U.S.A) (Table1).

Discussion

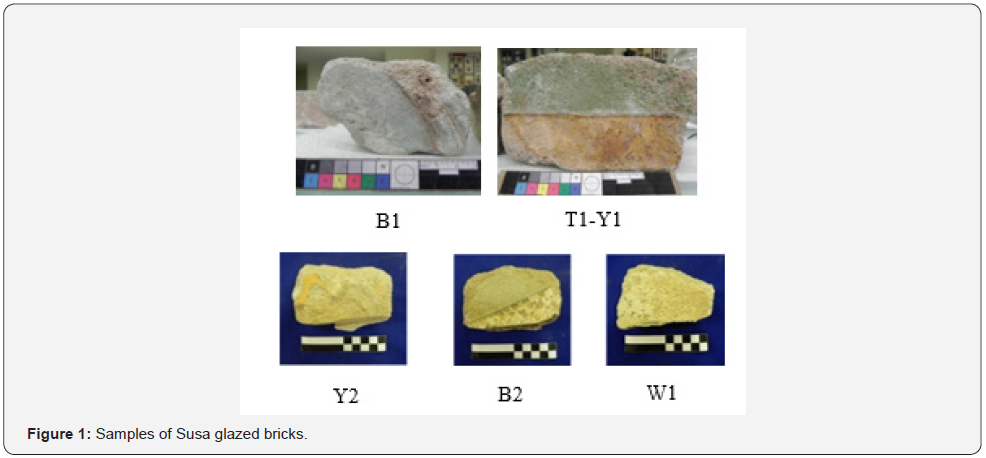

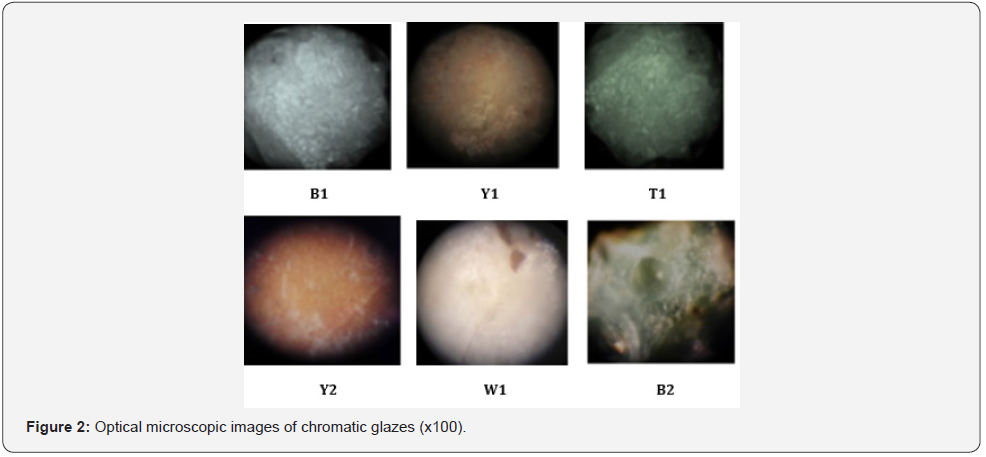

Achaemenid glazed bricks samples were observed by optical/light microscope to closely examine the deterioration of their surface, and comparing the physical exhaustion caused by the progression of deterioration process and their color (Cultrone, 2005) (Figure 1 & 2) demonstrate the surface exhaustion of the chromatic glazes and the differences in their color in the studied samples. Then, some samples of the chromatic glazes were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy method for finding out their elemental composition. Results provide useful information about the colors and the exhausted surface of the glazes as well as their elemental composition to identify their elements, and the feasibility of their quantitative comparison with each other in different samples.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES)

Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy method is capable of quantitative identifying of elements, even those in very low amounts without chemical interference and a very low detection limit. This method has been used during the recent years for studying and closely examining ceramic glazes both quantitatively and elemental, for the purpose of identifying the elements and different glazes pigments, even trace and rare elements, considering the amount of ions exiting from the chemical structure of glazes through the deterioration process, and assessing the extent to which they have been eroded even prior to the time that this deterioration appears on the surface May E [13]. This method is also used for provenance studies of the excavated works in archeometric studies. In some studies on the deterioration process of glazes, researchers could evaluate the extent to which the ions such as lead exit from the chemical structure of glazes in burial environments and also in acidity and different temperatures, and determine the relationship between the deterioration of glaze and these factors Szaloki [14], Huntly [15], Furthermore, many researches have been carried out using this method for identifying the elements and the technologies of making historical ceramic pieces in which transition pigment elements such as copper, cobalt and lead have been quantitatively and precisely identified in historical chromatic glazes, and also has been used for historically categorizing the studied ceramic works from different regions and studying the commercial relationships between different regions Mangone[16]. Many studies have been done for examining the elements and identifying different polychrome and blue monochrome, and for studying the reasons of differences between colors, identifying glaze opacifier agents, provenance studies and determining whether the studied ceramic works in different ancient sites of Italy such as Pompeii, Sisak etc. were local or were imported from other regions Mangone [17], Roncevic [18].

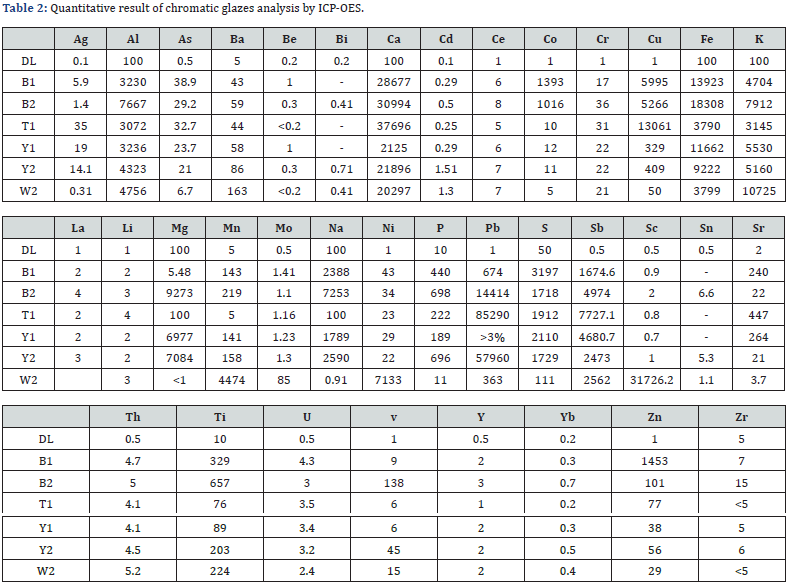

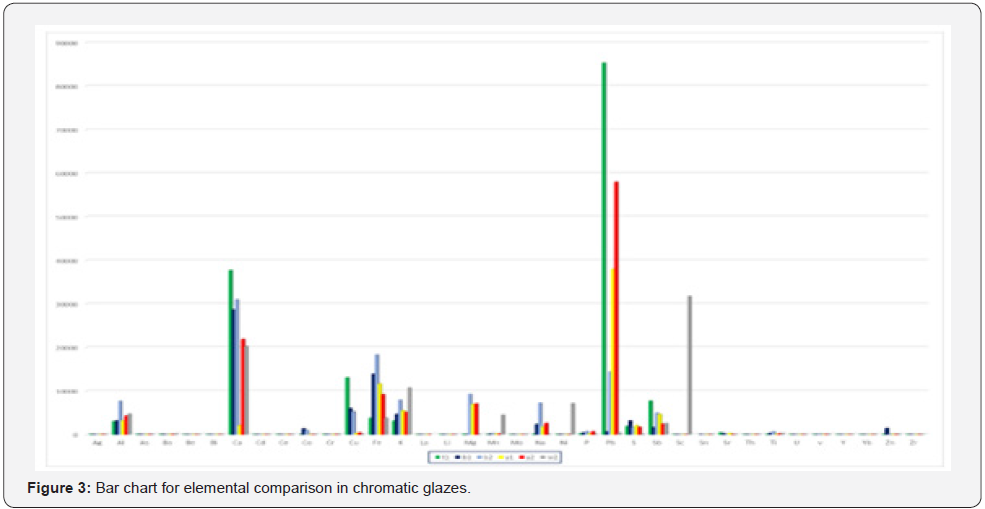

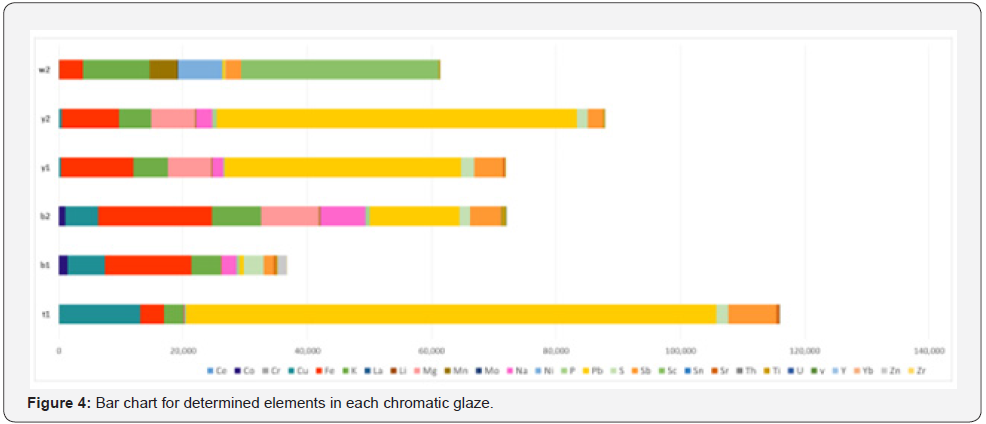

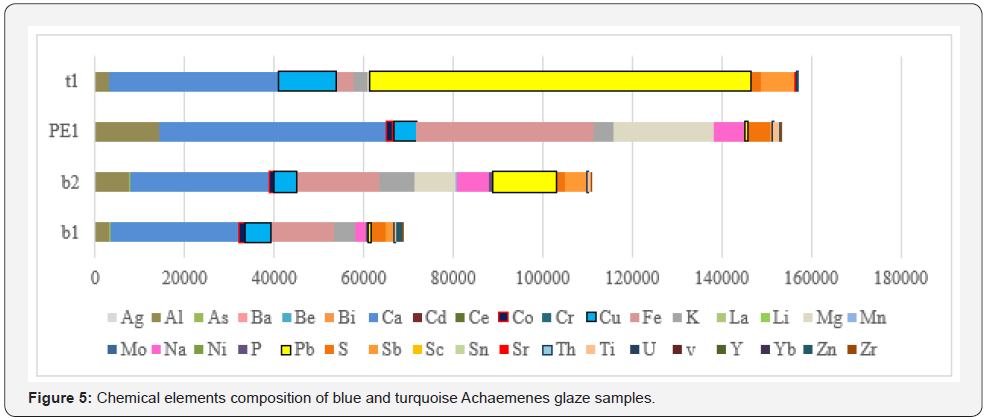

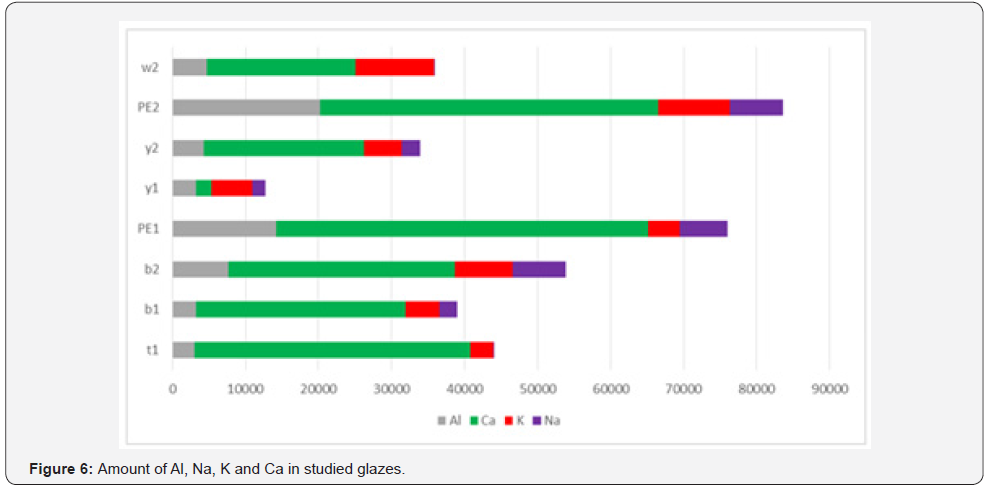

In the present study, too, the capacity of the precise analysis of inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy method for quantitatively identifying chromatic glazed bricks in white, yellow, blue, and turquoise of the Achaemenids belonging to Apadana Palace of Susa is being used, for element comparison of glazes, especially the role of transition elements in making two different colors of blue and green blue Orecchio [19]. Element quantitatively analysis of Achaemenid chromatic glaze samples with inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy method is presented in the following (Table 2), and a bar chart diagram is presented for the purpose of quantitative comparing of transition element pigments in the samples (Figure 3 & Figure 4). Results of elemental quantitative analysis demonstrate that the Achaemenid blue sample, B1, is consisted of 0.6 percent copper and 0.14 percent cobalt, which is the reason for existence of copper and cobalt pigments for making the blue color in this glaze sample. The amount of alkali and alkaline earth metals in this sample is reported to be 0.5 percent potassium and 0.24 percent sodium and 2.9 percent calcium. B2 sample consists of 0.53 percent copper and 0.1 percent cobalt, and the amount of alkali and alkaline earth metals of this sample is reported to be 0.72 percent sodium, 0.8 percent potassium and 3 percent calcium (Figure 5 & Figure 6). The reported amounts of elements from their elemental analysis are close to the amounts of copper and cobalt of Achaemenid sample of Parse Tall-e-Ajori, PE1, that have previously reported to be 0.48 percent copper and 0.13 percent cobalt. Also, in this sample the amount of alkali elements of the glaze includes 0.44 percent sodium and 0.65 percent potassium, which shows the similarity of the element composition of Achaemenid blue glazes in the two different regions Yousefnejad [12] and regarding the amount of 0.2- 0.5 percent of antimony reported to include in Achaemenid blue samples, we could consider the use of the compounds of this element as glaze opacifier agent in these samples [11,16].

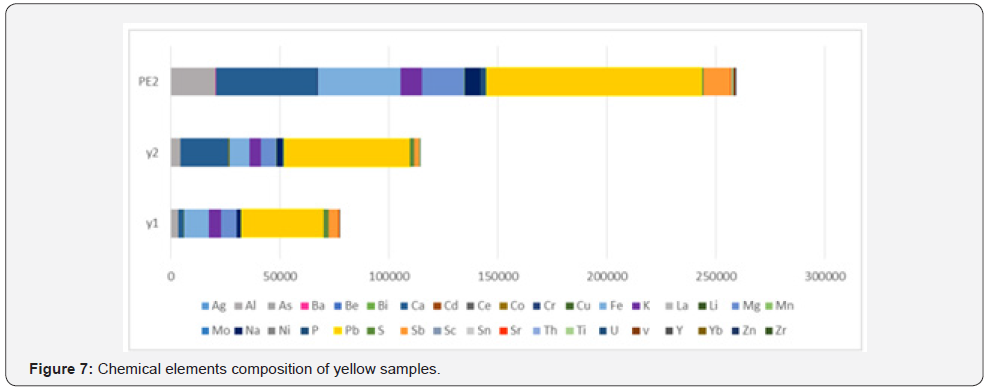

The Y1 sample of Achaemenid yellow includes more than 3 percent lead and 0.5 percent antimony. Y2 yellow sample too, is reported to include 5.8 percent lead and 0.25 percent antimony, that besides the existence of antimony as the opacifier material in the glaze, the existence of lead and antimony elements due to the yellow pigment of antimonate lead in the studied yellow samples Orecchio [19] and Padeletti [20, 21]. PE2 sample of Parse Tall-e-Ajori is reported to include 1.25 percent antimony and 9.8 percent lead Yousefnezhad [12]. Results are shown in the diagram pf (Figure 7) in a quantitatively comparative way. T1 turquoise glaze sample that has a green-blue color include 1.3 percent copper, 0.001 percent cobalt, 0.01 percent sodium, 0.31 percent potassium and 3.7 percent calcium. The considerable point about this color is that it includes 8.5 percent lead and 7 percent antimony, while the amount of chromium, that it can also make a green-blue color in the glaze, in this sample is 0.0031 percent and is very trifle in comparison with the reported amounts for copper, lead and antimony. Thus, the existence of yellow pigments of lead, antimony and copper blue at the same time could result in a green-blue color in T1 turquoise glaze sample. Besides, regarding the diagram of (Figure 4), the amount of alkali elements in this glaze is much less than the alkali elements in the blue glaze samples, thus besides the presence of yellow pigment, the different pH level of the glaze in comparison with the blue sample has also contributed to producing this color Eppler [6]. W2 white sample includes 2 percent calcium and 0.25 percent antimony that have resulted in the white and opaque mode of the glaze Maggetti [10]. The results are in accordance with other studies on this glaze done based on other methods that have reported calcium antimonate in the white sample Holakooei [11].

Conclusion

Studying the results from quantitative analysis of Achaemenid glaze samples from Apadana palace in Susa demonstrate that Y1 and Y2 yellow samples each include more than 3 percent and 5.8 percent lead, 0.5 percent and 0.25 percent antimony that is an agent resulting in yellow color due to yellow lead antimonate pigment Pb2 Sb2 O7. The white sample includes 2 percent calcium and 0.25 percent antimony that according to the results gained from this study demonstrates the presence of calcium antimonate that results in the white color of the glaze. The Achaemenid turquoise glaze that has a green-blue color includes 8.5 percent lead, 7 percent antimony and 1.3 percent copper. Thus regarding the results gained from quantitative elemental analysis one could say that the production of this color is due to the existence of a considerable amount of yellow lead pigment besides the copper blue pigment and the much less amount of alkali elements thus increase in the acidity of the glaze in comparison with its contemporary blue glazes B1 and B2, It means that the artist has used a compound of copper blue and lead antimonate yellow pigments in certain amounts that have resulted in a green-blue color in the turquoise glaze, and also reduced alkali elements amount and adjusted the acidity of the glaze. B1 and B2 Achaemenid blue glazes, are consisted of copper and cobalt, and the amount of copper in the samples are almost similar and about 0.5 percent, and the amount of cobalt in Achaemenid blue samples is about 0.1 percent, its function as evidence confirming the emergence of technical and artistic methods in creating different colors, it could also demonstrate the utilization of these rare elements in ancient Iran during Achaemenid dynasty. Studied Achaemenid samples are resorted to include antimony which shows the use of compounds including this element such as lead antimonate and calcium antimonate as an opacifier agent in this glaze. Thus, it could be concluded that in considerable glaze making techniques during Achaemenid period such as identifying and utilizing different mineral pigments and compounding them for making a new variety of chromatic glazes and controlling over the conditions of glaze compounds such as its alkali material in creating different colors for glazing the bricks used for decorating the palaces and important buildings of those ages.

References

- Moortgat, Anton, Filson, Judith (1969) Art of Ancient Mesopotamia: The Classical Art of the Near East. Phaidon Press Ltd, Tehran, Iran pp. 296-302.

- Ghirshman R (1993) Tchoga. Zanbil. Dur-Untash. Cultural Heritage Foundation Publication Tehran.

- Briant Pierre (2002) From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Eisenbrauns. Ghatreh publication pp. 132-34

- Caubet A, Kaczmarczyk A (1998) Les brique glacureés du palais Darius, Techné: La scinse au service de l'histoire de l'art et des civilizations. (7): 23-26.

- Prudence O Harper, Joan Aruz, Francoise Tallon (1993) The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasure in the Louvre. Metropolitan museum pp. 223-225.

- Eppler Richard A (1998) Glazes and glass coatings. The American Ceramic Society 735 Ceramic Place Westerville, Ohio USA pp. 148-151.

- Zhu Wang Zhao (1999) Advanced inductively Coupled plasma – mass spectrometry Analysis of Rare Earth Elements. Balkema, Rotterdam, Netherlands pp. 14.

- Jung M (2004) Persiens antike Pracht: Bergbau, Handwerk, Archäologie: Katalog der Ausstellung des Deutschen Bergbau-Museums Bochum vom 28. Veröffentlichungen aus dem Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum, 128. Stöllner Thomas, Slotta Rainer and Vatandoust Abdolrasool (Editors). Deutsches Bergbau-Museum, Germany pp. 391-392.

- Tite Mike S, Shortland AJ (2004) Report on the scientific investigation on a glazed brick: the glazing. In Book. Persiens antike Pracht: Bergbau, Handwerk. Archäologie: Katalog der Ausstellung des Deutschen Bergbau-Museums Bochum.

- Maggetti M, Neururer CH (2009) Antimonate opaque glaze colors from the faience manufacture of le bois d’é Archaeometry 51(5):791-807.

- Holakooei P (2014) A technological study of the Elamite polychrome glazed bricks at Susa, South-Western Iran. Archaeometry 56(5): 764-783.

- Yousefnejad S, Vahidzadeh R, Talebian MH (2013) Archaeometrical study of Achaemanid glazed bricks of Tall-e-Ajori in Parse by multiple instrumental analysis methods. Journal of Archaeological Studies 5(1): 165-179.

- May Eric, Jones Mark (2006) Conservation Science Heritage Materials. The Royal Society of Chemistry pp. 67.

- SzaloÂki I (2000) Quantitative characterisation of the leaching of lead and other elements from glazed surfaces of historical ceramics. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 15: 843-850.

- Huntley DL (2007) Local recipes or distant commodities? Lead isotope and chemical compositional analysis of glaze paints from the Salinas pueblos. Journal of Archaeological Science 34: 1135-1147.

- Mangone, Annarosa, et al (2009) Manufacturing expedients in medieval ceramics in Apulia. Journal of Cultural Heritage 10: 134-143.

- Mangone A, De Benedetto GE (2011) A multianalytical study of archaeological faience from the Vesuvian area as a valid tool to investigate provenance and technological features. New J Chem (35): 2860-2868.

- Roncevic Sanda, Svedruzic Lovorka Pitarevi (2012) Determination of chemical composition of pottery from antic Siscia by ICP-AES after enhanced pressure microwave digestion. Anal. Methods (4): 2506-2514.

- Orecchio Santino (2013) Micro analytical characterization of decorations in handmade ancient floor tiles using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). Microchemical Journal 108: 137-150.

- Padeletti G, Fermo P (2004) Production of gold and ruby-red lustres in Gubbio (Umbria, Italy) during the Renaissance period. Appl. Phys. A 79: 241-245.

- Padeletti G (2004) Technological study of ancient ceramics produced in Casteldurante (central Italy) during the Renaissance. Applied Physics A 79(2): 335-339.