Cause-Specific Mortality Patterns among Hospital Deaths in District Mardan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Fazal Hassan1*, Sohail Akhtar1, Muhammad Rafiq2, Muhammad Imran Khan1, Riaz Ahmad Khan1 and Jawad Ali1

1Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Haripur, Haripur, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

2Department of Statistics, The University of Malakand, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Submission: December 13, 2022; Published: January 02, 2023

*Corresponding author: Fazal Hassan, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Haripur, Haripur, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

How to cite this article: Fazal H, Sohail A, Riaz Ahmad K, Muhammad R, Jawad A. Cause-Specific Mortality Patterns among Hospital Deaths in District Mardan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Ann Rev Resear. 2023; 8(2): 555732. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2023.08.555732

Abstract

Background: All the patterns of mortality and encumbrance of diseases in a residential area can be observed from the patients admitted to a hospital. Mortality is the oldest well-known healthcare indicator and an important instrument for planning and well organizes management purposes in hospitals. This study was carried out to evaluate the cause-specific mortality patterns among hospital deaths in Mardan district, Pakistan.

Methods: The study was conducted between April 2018 to April 2019 in admitted patients in District Headquarter Mardan. 200 samples of deaths were collected through a questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of the information age, sex, residence, and causes of death. SPSS 21 version was used for statistical analysis. Study area map was design through ArcGIS version 10.8.

Results: As per our results 138 (69%) were males and 62 (31%) were females. Maximum deaths occurred based on age 46-60 years (25.50%) followed by 31-45 years (24.50%), 61-75 years (20%), 16-30 years (17.50%), 1-15 years (5.50%), 76-90 and 91-105 years combine (3.50%) respectively. The deaths in rural areas 129 (64%) and urban areas were 71 (35.5%). The leading cause of mortality was RTA (13.50%), followed by femoroacetabular impingement (13%), chest pain and dextromethorphan (DM) (8%), poisons case (7.5%), hypertension and heart failure (6.50%), cerebrovascular accident (CVA) (5.50%), shortness of breath (SOB), renal failure and chronic liver disease (CLD) (4.50%), head injury and stroke (3.50%), hepatitis C virus (HCV) (2%) and other diseases (9%) respectively.

Conclusion: The majority of deaths occur in the age of 46-60 in Mardan hospital. The proportion of deaths was large in males than females. Residence-wise mortality in rural areas was large than in urban areas. The leading cause of mortality is road traffic accidents (RTA). It is suggested, the policymaker should devise strategies to minimize accidents. It is further suggested that to make health care centres in rural areas and to depute trained medical staff.

Keywords: Mardan; Pakistan; Hospital mortality; Cause-specific mortality rate; Estimated mortality

Abbreviations: DM: Dextromethorphan; CVA: Cerebrovascular accident; SOB: Shortness of breath; CLD: Chronic liver disease; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; RTA: Road traffic accidents; HAP: Household air pollution; PDHS: Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey; DHQ: District Head Quarter; AMC: Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita; DM: Dextromethorphan; CVA: Cerebrovascular accident; SOB: Shortness of breath; CLD: Chronic liver disease; HCV: Hepatitis C virus

Introduction

All the patterns of mortality and encumbrance of diseases in a residential area can be observed from the patients admitted to the hospital [1]. Mortality is the oldest well-known healthcare indicator and an important instrument for planning and well-organized management purposes in hospitals [2]. The patterns of mortality in a healthcare setting are more stirred by the state of hospitalization and type of illness among each other [3]. Government and international health agencies need exact information on important causes and patterns of mortality in different populations so that they can help in developing and nursing effective health policies and programs [4]. Policymaker’s first measure healthcare quality and those who trust such measurements can push quality improvement programs. The causes of many illnesses, as well as the grade of care delivered, are reflected in mortality data from hospitalized patients. Records of significant occurrences, such as an important factor are mortality components of the healthiness data system [5]. The reasons for mortality are frequently unwell documented in some rising nations; therefore, the health care policies of those countries are very poor. Unluckily, in many developed states, nationwide information is inconsistency and unreliability, and research focused on hospitals are limited because more deaths occur in other areas [6].

Each year, more than 500,000 mothers die as a result of pregnancy-related avoidable causes such as hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, sepsis, premature labor, and botched abortion. Ninety-nine percent of these deaths occur in underdeveloped countries [7]. Child mortality is a significant indication of a country’s development and a reflection of its goals and values [8]. Every day, more than 26,000 children under the age of five die around the world, most of them from preventable causes, according to WHO. They are almost all from underdeveloped countries. More than a third of young children die in their first month of life, most often at home and without access to basic health care and commodities that could save their lives [9]. In 2010, 7.6 million children have died before reaching the age of five worldwide, with neonatal fatalities accounting for 40% of these deaths. Pakistan has the world’s third highest rate of newborn death. It is critical to investigate factors related with newborn death before implementing evidence-based strategies to reduce mortality rates [10-11]. RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) is a major cause of newborn mortality rates, and it is a potential target for maternal immunization methods. However, data on the role of RSV in the deaths of young infants in impoverished nations is scarce [12]. Household air pollution (HAP), primarily by fuel for cooking, is one of the leading causes of respiratory disease and death in children under the age of five in poor and middle-income countries such as Pakistan. Using data from the 2013 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS), this study explores for the first time the relationship between HAP by fuel for cooking and under-five mortality [13].

Policymakers need reliable evidence about age, rates, and reasons for deaths in different units of the community. Lack of country-wide accurate and reliable data missing to identify the cause of death [6]. Population condition is required to study shortterm movements of the mortality rate of many goals. The change of deaths overtime is normally analysed by the rate of death growth. Mortality is one of the serious issues not only in Pakistan but all over the world and increases their rate day by day because of population increases. This cross-sectional study was carried out to evaluate the cause-specific mortality patterns among hospital deaths in Mardan district, Pakistan.

Methods

Study Design, Area and Period

This study was conducted in District Mardan hospitals. The total population of district Mardan was 2,373,061, male 1,200,871 and females 1,172,112 and 78 transgender. Most of the population is living in rural areas and about 0.4 million living in urban areas. In district hospitals Mardan, the majority of patients belong to the local areas of Takht Bhai, Katlang, Bakhshaly, Mayaro, Shergargh, Lund khwar and Mardan.

Data description

The data was collected through a questionnaire. We used secondary data for our analysis, a total of 200 samples of registered deaths were collected from District Head Quarter (DHQ) Hospital Mardan between April 2017 to April 2018. The questionnaire was consisting of sex, age, residence and causes of deaths.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed through a statistical package SPSS 21 version. Descriptive analysis was performed as (means ± SD) for continuous variables and as frequency and %age for categorical variables. Chi-square (χ2) test was used to ascertain the association between categorical variables. The significance level was measured at the probability level (P ≤ 0.05).

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance was achieved from the University of Malakand Chakdara Pakistan vide ethical number UoM/Ethics/ Comm./2018/. Permission was obtained to collect the data from the DHQ hospital Mardan authority.

Results

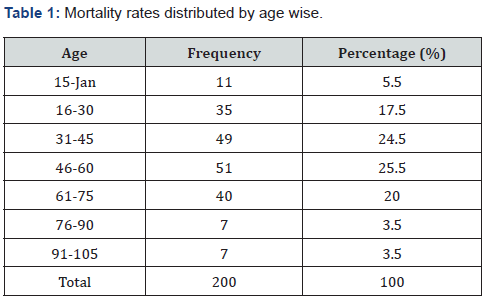

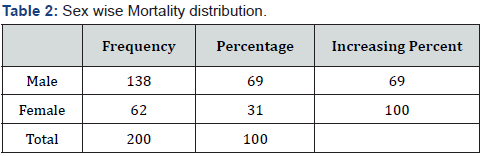

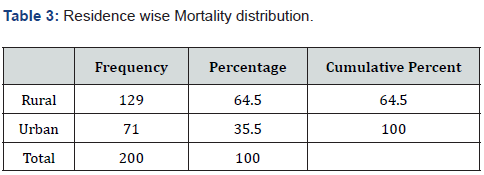

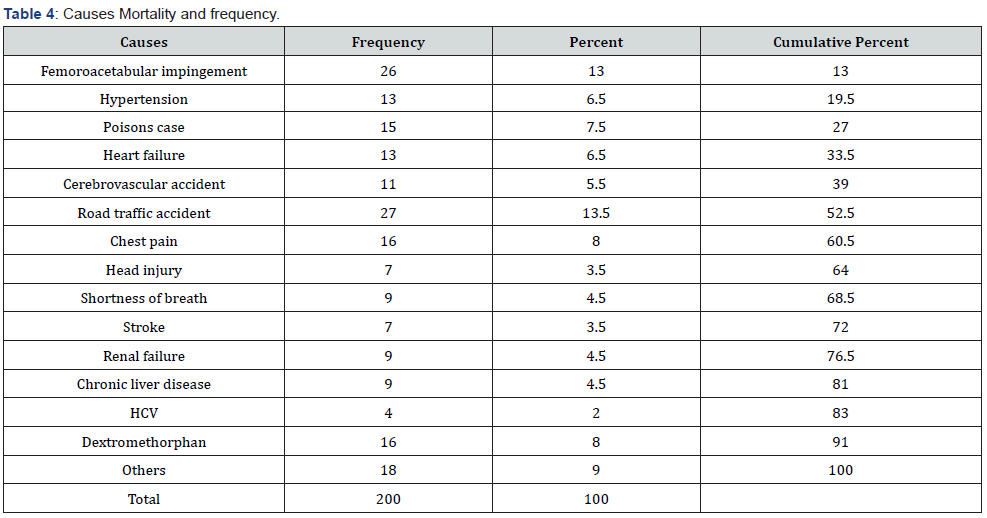

Table 1 reveals the age wise mortality distribution. The majority of deaths occurred at the age group of 46-60 years 51 deaths (25.50%) followed by 31-45 years 49 (24.50%), 61-75 years 40 (20%), 16-30 years 35 (17.50%), 1-15 years 11 (5.50%), 76-90 and 91-105 years 7 deaths (3.50%) respectively. Table 2 shows the sex wise mortality distribution. The ratio of deaths in males 138 (69%) are greater than females 62 (31%). The majority of deaths belong to rural areas (Table 3). The deaths in rural areas are 129 (64.5%) and urban areas are 71 (35.5%). Table 4 depicts that the leading cause was road traffic accident (RTA). The leading cause of mortality was RTA 27 (13.5%), followed by femoroacetabular impingement 26 (13%), other diseases 18 (9%) respectively. In other diseases including fever, electric shock, history off, recorded dead body, firing, severe pain and arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (AMC). Then chest pain and dextromethorphan (DM) was 16 (9%), followed by poisons case 15 (7.5%), hypertension and heart failure 13 (6.5%), cerebrovascular accident (CVA) 11 (5.50%), shortness of breath (SOB), renal failure and chronic liver disease (CLD) 9 (4.50%), head injury and stroke 7 (3.50%) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) 4 (2%) respectively.

Discussion

Registering dynamic measures, particularly mortality, is an important in order to study the early causes of mortality and strategy efficiently for health improvement systems. This cross-sectional study was designed to assess the cause-specific mortality patterns among hospital deaths in Mardan district, Pakistan. Fewer studies are conducted to assess causes and deaths in Pakistan to provide the exact information to policy maker. From 2011 to 2015, the death rate at Ardebil Hospital revealed a male to female ratio of 1.36. Among all hospital deaths, male was 57.8% and females were 42.2% [14]. Research studies by Tariq et al. [15], Pattaraarchachai et al. [16] and Foruzanfar et al. [17] revealed related result in terms of the sex ratio of the dead. Moore & Wilson [18] recommended that males are more likelihood to decease than females from infectious and parasitic diseases. This may be due to differences in the immunity of males and females to these infections. Central and Eastern Europe had higher all-cause and cardiovascular death rates in men and women aged 75–84 than Western Europe [19,20]. Over the last three years, all-cause death rates differed by a ratio of 2/2.5 when comparing the country with the highest rate to the country with the lowest rate (men, women). This ratio accounted for about 4/5 of overall cardiovascular mortality (men, women). Most European countries saw a decrease in all-cause and total cardiovascular mortality rates between 1970 and 1996 [21].

There were 53 (63%) male patients and 31 (37% female) patients in total. The patients’ average age was 42+17 years. Rheumatic valve disease was a risk condition in 34 (41%) of the patients. The mitral valve was perhaps the most commonly impacted valve in 43 (51 percent) of patients, and the most usually isolated pathogen was methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in 12 patients (14.3 percent). Total in- hospital mortality was 27(32.1%), with 18(21%) patients developing congestive heart failure, 15(18%) developing arrhythmias, 16(19%) developing peripheral embolism, and 38 patients developing renal failure (54 percent). Furthermore, 17 individuals (20% of the total) required surgical treatment [22]. Over the course of 18 months, the intervention was executed in a population of 283324. The intervention was given to 3200 pregnant mothers. Significant enhancements in antenatal care (92 percent vs 76 percent, p< .001), TT vaccination (67 percent vs 47 percent, p< .001), institutional delivery (85 percent vs 71 percent, p< .001), cord application (51 percent vs 71 percent, p< .001), delayed bathing (15 percent vs 43 percent, p.001), colostrum administration (83 percent vs 64 percent, p< .001), and breast - feeding initiation within [23,24].

Improved surveillance network accuracy and coverage resulted in higher maternal, perinatal, and neonatal mortality rates when compared to mortality rates from the routine monitoring system 1.5 years previously. Perinatal mortality was 60 per 1000 live births (p = 0.001). Maternal mortality was 247 per 100,000 live births (p = 0.36), neonatal mortality was 40 per 1,000 live births (p 0.001), and perinatal mortality was 40 per 1,000 live births (p 0.001). (p 0.001). All mortality rates were greater than province and national statistics reported by foreign agencies, according to repeated Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys and forecasts [25,26]. This study results reveals that the majority of deaths occurred at the age group of 46-60 years 51 deaths (25.50%) followed by 31-45 years 49 (24.50%), 61-75 years 40 (20%), 16-30 years 35 (17.50%), 1-15 years 11 (5.50%), 76-90 and 91-105 years 7 deaths (3.50%) respectively. The ratio of deaths in males 138 (69%) are greater than females 62 (31%). The majority of deaths belong to rural areas. The deaths in rural areas are 129 (64.5%) and urban areas are 71 (35.5%). The first reason is that the majority of the population in district Mardan belongs to rural areas and secondly, in rural areas the health facilitation is very poor. The leading cause of mortality was RTA 27 (13.5%), followed by femoroacetabular impingement 26 (13%), other diseases 18 (9%) respectively.

One of the greatest impediments to the successful death registration process in Pakistan is that the authorities in charge work independently and in isolation. We recommend that the country establish a centralized meta-electronic registration process based on the experiences of the electronic system for registering mortality in high-income countries that have a centralized database. Due to the low level of identification of deaths reported in this study between April 2018 to April 2019, as well as the role of information registration in health policymakers, the current registration system appears incapable of providing adequate information for the development of health care programs in Pakistan. As a result, alternative, low-cost, and timely methodologies for descriptive epidemiological estimating of the population are required. The method utilized in this study has the advantage of comparing the predicted rate of death in the form of cause-specific mortality groups, which are important in decision-making and policy formulation.

Conclusion

The majority of deaths occur in the age of 46-60 in Mardan hospital. The proportion of deaths was large in males than females. Residence-wise mortality in rural areas was large than in urban areas. The leading cause of mortality is road traffic accidents (RTA). It is suggested, the policymaker should devise strategies to minimize accidents. It is further suggested that to make health care centres in rural areas and to depute trained medical staff.

References

- Mboera LE, Rumisha SF, Lyimo EP, Chiduo MG, Mangu CD, et al. (2018) Cause-specific mortality patterns among hospital deaths in Tanzania, 2006-2015. PLoS One 13(10): e0205833.

- Pattaraarchachai J, Rao C, Polprasert W, Porapakkham Y, Pao-In W, et al. (2010) Cause-specific mortality patterns among hospital deaths in Thailand: validating routine death certification. Population health metrics 8(1): 1-2.

- Kharel S, Bist A, Mishra SK (2021) Ventilator-associated pneumonia among ICU patients in WHO Southeast Asian region: A systematic review. PloS one 16(3): e0247832.

- Karki RK (2016) Mortality patterns among hospital deaths. Kathmandu University Medical J (KUMJ) 14: 65-68.

- Bell CM, Redelmeier DA (2021) Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. New England Journal of Medicine 345(9): 663-668.

- Aziz S, Ejaz A, Alam SE (2013) Mortality pattern in a trust hospital: a hospital-based study in Karachi. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 63: 1031-1035.

- Nisar N, Abbasi RM, Chana SR, Rizwan N, Badar R (2017) Maternal Mortality in Pakistan: Is There Any Metamorphosis Towards Betterment? Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad. JAMC 29(1):118-22.

- Wagstaff A (2000) Socioeconomic inequalities in child mortality: comparisons across nine developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78: 19-29.

- Organization WH (2019) Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division.

- Nisar YB, Dibley MJ (2014) Determinants of neonatal mortality in Pakistan: secondary analysis of Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2006-07. BMC public health 14: 663.

- Duby J, Pell LG (2020) Effect of an integrated neonatal care kit on cause-specific neonatal mortality in rural Pakistan 13(1): 1802952.

- Kazi AM, Aguolu OG, Mughis W, Ahsan N, Jamal S, et al. (2021) Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Mortality Among Young Infants in Karachi, Pakistan: A Prospective Postmortem Surveillance Study. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 73(Suppl_3): S203-s209.

- Naz S, Page A, Agho KE (2017) Household air pollution from use of cooking fuel and under-five mortality: The role of breastfeeding status and kitchen location in Pakistan. PloS one 12(3): e0173256.

- Mahmood Y, Ishtiaq S, Khoo MBC, Teh SY, Khan H (2021) Monitoring of three-phase variations in the mortality of COVID-19 pandemic using control charts: where does Pakistan stand? International journal for quality in health care: journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 33(2): mzab062.

- Tariq MJW, Ansari T, Awan S, Ali F, Shah M, et al. (2009) Medical mortality in Pakistan: experience at a tertiary care hospital. Postgrad Med J 85: 470-474.

- Pattaraarchachai JRC, Polprasert W, Porapakkham Y, Pao-in W, Singwerathum N, et al. (2010) Cause-specific mortality patterns among hospital deaths in Thailand: validating routine death certification. Population Health Metrics.

- Forouzanfar MSS, Shahraz S, Dicker D, Naghavi P, Pourmalek F, et al. (2014) Evaluating causes of death and morbidity in Iran, global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study 2010. Arch Iran Med 17(5): 304-320.

- Moore SLWK (2002) Parasites as a viability cost of sexual selection in natural populations of mammals. Science.

- IP O (2002) Sex differences in mortality rate. Science.

- (2001) Organization GWH. World Health Statistics. World Health Organization.

- Akbari MNM, Soori H (2006) Epidemiology of deaths from injuries in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J 12(3-4): 382-390.

- Pop CPL, Dicu D (2004) Epidemiology of acute myocardial infarction in Romanian county hospitals: a population-based study in the Baia Mare district. Rom J Intern Med 42(3): 607-623.

- Kesteloot H, Sans S, Kromhout D (2002) Evolution of all-causes and cardiovascular mortality in the age-group 75–84 years in Europe during the period 1970–1996. A comparison with worldwide changes. European heart journal 23(5): 384-398.

- Arshad S, Awan S, Bokhari SS, Tariq M (2015) Clinical predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with infective endocarditis at a tertiary care center in Pakistan. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 65(1): 3-8.

- Memon ZA, Khan GN, Soofi SB, Baig IY, Bhutta ZA (2015) Impact of a community-based perinatal and newborn preventive care package on perinatal and neonatal mortality in a remote mountainous district in Northern Pakistan. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 15: 106.

- Anwar J, Torvaldsen S, Sheikh M, Taylor R (2018) Under-estimation of maternal and perinatal mortality revealed by an enhanced surveillance system: enumerating all births and deaths in Pakistan. BMC public health 18(1): 428.