Quality of Life in Patients with T2D The Role of Demographic and Clinical Factors

Paraskevi Theofilou1,2*

1General Hospital “Sotiria”, Athens, Greece

2Helenic Open University, School of Social Sciences, Patra, Greece

Submission: December 13, 2022; Published: December 22, 2022

*Corresponding author: Paraskevi Theofilou, General Hospital “Sotiria”, Athens, Helenic Open University, School of Social Sciences, Patra, Greece

How to cite this article: Theofilou P. Quality of Life in Patients with T2D The Role of Demographic and Clinical Factors. Ann Rev Resear. 2022; 8(2): 555731. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2022.08.555731

Abstract

Background: In recent decades, efforts have been made to develop diabetes prevention and health promotion programs to reduce the prevalence of the disease and to control its complications. In order to achieve such goals, studies that investigate the health-related quality of life of diabetic patients and which aim to identify different kinds of factors that affect the disease are highly essential. Physical and emotional fatigue influences T2D patients’ ability to manage their condition. So, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of fatigue on the quality of life (QoL) of diabetic patients and addition all the potential effect of different sociodemographic and clinical factors both in terms of fatigue and QoL.

Methods: In this quantitative cross-sectional study sufferers from T2D (N=134) completed the FAS for fatigue and ADDQOL. Non-parametric tests (Spearman correlation analysis, Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal Wallis test) were run to study the relationship among patients’ fatigue, QoL, socio-demographic and clinical factors.

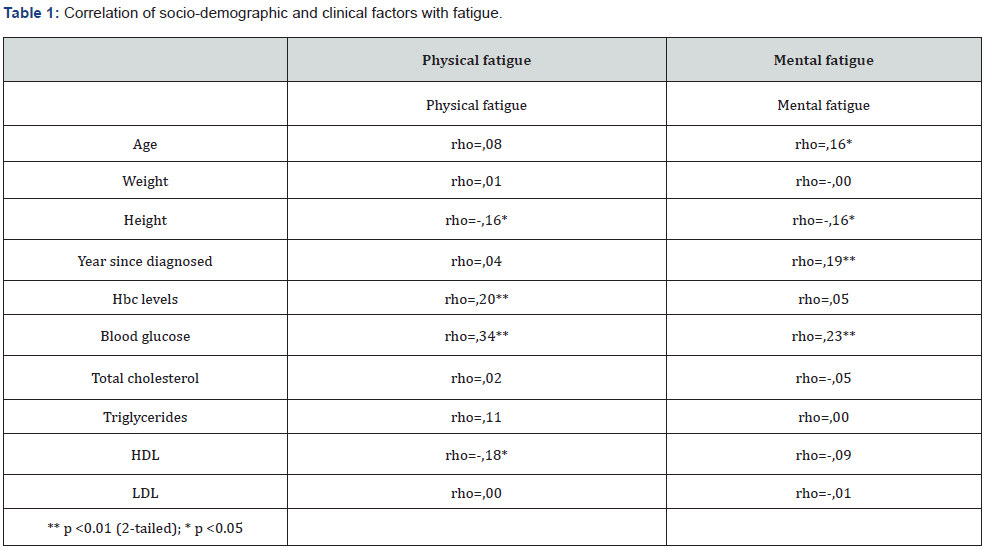

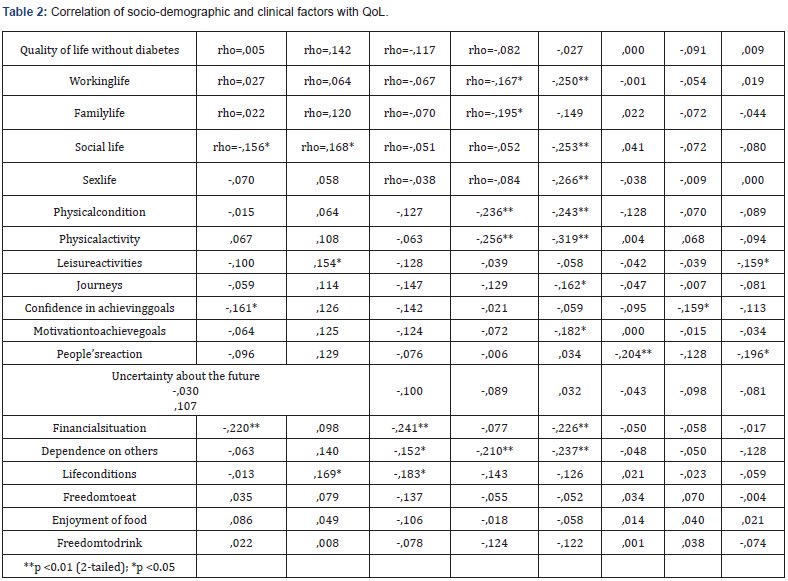

Results: A statistically significant positive correlation was observed between the dimensions of fatigue and age, years of diagnosis, Hbc and blood glucose. On the contrary, there was a statistically significant negative relationship between fatigue, height and HDL. Similarly, there was a statistically significant negative correlation between QoL and age, years since diagnosed, Hbc, blood glucose, LDL, triglycerides and cholesterol, whereas a statistically significant positive correlation was noted between dimensions of QoL and height. Several other factors such as gender, duration of illness, hypertension, marital status, place of residence, education, type of treatment, smoking and other health complications seemed to affect both patients’ fatigue and QoL.

Conclusion: Both the QoL and fatigue of such patients are affected by different sociodemographic and clinical variables. These findings could be the basis for new research, focusing on additional factors that affect T2D, while they should be carefully taken into consideration by the health experts when planning health promotion interventions for this population.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus; Fatigue; Quality of life; Sociodemographic; Clinical factors

Abbreviations: QoL: quality of life; T2D: Type 2 diabetes; FAS: Fatigue Assessment Scale

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is one of the most common chronic diseases as according to the International Federation of Diabetes 424.9 million people worldwide suffer from it and by 2045 it is estimated that this number will increase to 628.6 million. In Europe particularly, 58 million diabetics have been registered, i.e., 8.8% of the population, and it is likely that this percentage will increase to 10.2% by 2045 [1]. The diseases can occur at different times in a person’s life. Its causes are both genetic and environmental. Daily treatment of diabetes involves a complex and demanding program. Adapting to this program is difficult and behavior change tips are insufficient to keep up with the complexities of managing the disease. Many self-care behaviors are involved in daily treatment: dietary restrictions, glucose monitoring, regular exercise, daily insulin injections, good nutrition and sleep, adjusting insulin doses according to food intake and physical activity levels, smoking cessation, care of the lower limbs and an effort to avoid a hypoglycemic episode [2].

The factors that can affect a chronic illness, such as diabetes, are internal, environmental (external), and those related to the disease itself. Internal factors include gender, age, socioeconomic status, spirituality, maturity, adaptability, beliefs about health and illness, or pre-existing organic or mental illness. Environmental factors concern the family as well as the social environment, food costs and quality and the feasibility of engaging in physical activity [3].

Fatigue

The feeling of fatigue is a subjective experience and due to its subjectivity, it is difficult to define. It is in fact a complex of psychological, social and biological processes and can be described as a condition, which is characterized by a decrease in the efficiency of the individuals and in their ability to cope, while usually accompanied by a feeling of drowsiness or irritability [4]. Typically, the different meanings of fatigue incorporate at least two fundamental factors: duration and severity, while the dimensions related to it are distinguished in physical and mental fatigue [5-7]. Physical fatigue is characterized by difficulties and reduced ability to perform physical work due to previous physical exercise [8]. As a result, it leads to lowered endurance, movement control and productivity, general feeling of discomfortand it adversely affects the quality of work, social relationships and activities [9-10]. On the other hand, mental fatigue reflects reduced cognitive abilities and less willingness to act according to the requirements of the specific task owing to previous physical or mental effort [11]. In other words, fatigue is generally associated with persistent and significant exhaustion, physical or mental, or both.

Fatigue in people with diabetes is multidimensional, including organic, psychological and lifestyle factors [12]. Consequently, it is clear that in this context emotional causes have a crucial role. The symptoms of hypoglycemia, the duration of the disease and age are some of those that have been found to be positively associated with fatigue [13]. A typical example is also being overweight and engaging in low levels of physical activity, which have been strongly associated with fatigue and are of particular clinical importance to many patients with diabetes, as many people with insulin resistance T2D are overweight or obese [12].

In a study of African American women with T2D on diabetes self-management, they found that fatigue limited their ability to exercise [14]. Also, the study of Singh et al. [15], which studied the effect of fatigue on the quality of life of diabetic patients, showed that fatigue is negatively related to quality of life and functional status. Fatigue was one of the main concerns of Australian women, who also reported that they had limited their social activities and / or limited their activities to what they deemed necessary [16]. Another recent hospital study of patients with diabetic neuropathy found that 34.6% of the sample had fatigue problems, while 22.4% reported symptoms of fatigue for more than 6 months. Additionally, 18.8% of patients who experienced fatigue reported that fatigue in combination with diabetes was one of the 3 most serious problems that concerned them. Specifically, the results of the study demonstrated that fatigue is an important symptom with a significant effect on the quality of life of diabetic patients, which seems to be affected by the duration of the disease [17]. These findings suggest that fatigue complicates the management of diabetes because it is largely a self-managed disease that requires both physical and mental energy to accomplish the daily self-management tasks necessary to maintain optimal health [12].

Quality of life and T2D

T2D as a chronic metabolic disease is characterized by the complexity of its effects at the individual, family and social levels. According to various studies, diabetes has been shown to have an effect on the physical, social and psychological dimensions of quality of life [18-19]. Quality of life encompasses all aspects of a person’s life, such as health, housing, work, the environment. It includes personal preferences, experiences, perceptions and attitudes related to cultural, philosophical, psychological, economic, spiritual, political and interpersonal dimensions of daily life [20]. One of the most important aggravating factors of QoL associated with diabetes is the chronicity of the disease, which creates conditions of insecurity for the patients and their family regarding its course and outcome. Diabetes mellitus, like any chronic disease, tests physically and mentally the endurance of the patients and their family environment by having a catalytic effect on basic functions of the individual, such as communication, sociability and self-care [2,21]. The depletion of the patient’s physical and mental reserves also has as a result his poor therapeutic compliance [22].

The results of studies on the QoL of patients with diabetes have exhibited that there is a correlation between the QoL and HbA1c, age, female gender, obesity, insulin therapy, education, marital status, depression, insomnia, social support, as well as personality traits [18,23-28]. Specifically, it has been observed that in diabetes there is an interaction of the sufferers’ beliefs and values with their state of physical health. On the one hand, the disease itself creates a negative climate in the daily life of the individuals and on the other hand the individuals with their behaviors can bring about these negative effects [18]. Also, the coexistence of complications or other diseases have a negative effect on the QoL of such patients as they increase the likelihood of symptoms and / or disabilities [2,29]. The occurrence of complications, such as retinopathy or kidney disease, results in a reduction in both the patients’ QoL and their life expectancy, while at the same time the chances of developing further disabilities due to blindness, mutilation and others are increased. These disabilities are aggravating factors at the individual, family and socio-economic level as well [18]. Fatigue associated with this disease affects the mental health and quality of life of these patients.

In conclusion, it is clear that the factors that contribute to the onset of diabetes are different and varied. In spite of the fact that relevant studies have been conducted, the number of Greek studies related to this topic is very restricted. Consequently, the novelty of the research is based on the fact that no similar studies have been carried out in Greece regarding the evaluation of fatigue and its effect on the QoL of people with T2D, especially when in this country it is observed that the lack of diet and physical activity can lead to T2D addressing in this way issues related to QoL and fatigue. The purpose of this study is to investigate the existence of fatigue, its effect on QoL and the factors that affect them both (fatigue and QoL). We mainly hypothesize that the relation between fatigue and QoL will be statistically significant indicating a strong association of fatigue with important aspects of QoL, such as working, family and social life, sex life, physical condition, physical activity and leisure activities.

Method

Study design

This is a quantitative cross-sectional study including variables of fatigue, QoL and clinical as well as sociodemographic variables.

Participants

The study consisted of a sample of convenience and in particular it involved 134 patients who provided full data of whom 71 were men and 63 women. The data collection took place in general hospitals located in cities of Greece and it lasted approximately 5 months. In order to participate in this study, the patients should have been over 18 years old, they should have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, they should have given their voluntary consent, they had to speak the Greek language and finally their general state of health had to allow them to take part in the study.

Questionnaires

Participants completed the “The Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS)”, which is a tool for assessing perceived fatigue and consists of 10 questions on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always). Five questions are about physical, and five questions are about mental fatigue. This scale is considered a reliable tool for measuring fatigue for both healthy people and people with diseases [30-32]. In the present study, the ADDQOL quality of life questionnaire was also used. This tool consists of 20 questions, related to specific areas of quality of life of patients with diabetes, which are the following a) Present quality of life, b) Quality of life without diabetes, c) Working life, d) Family life, e) Social life, f) Sex life, g) Physical condition, h) Physical activity, i) Leisure activities, j) Journeys, k) Confidence in achieving goals, l) Motivation to achieve goals, m)People’s reaction, n)Uncertainty about the future, o)Financial situation, p) Dependence on others, q) Life conditions r) Freedom to eat, s) Enjoyment of food, t) Freedom to drink. The QoL scale includes items on physical activity, confidence, motivation, and other topics that seem to be conceptually linked in the idea of fatigue. Nevertheless, the FAS concentrates exclusively on the existence of physical and mental fatigue.

Procedure

Permission was obtained from the Scientific Council of the Hospitals to conduct the research. The researchers informed the patients orally about the aims of the study and then they provided the questionnaire, which was accompanied by a letter that stated information about the purpose and the voluntary nature of the study as well as the anonymity and confidentiality of the data. Completion of the questionnaire meant acceptance of participation and informed consent, while the duration of its completion did not exceed 20 minutes.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the sample was checked using the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. However, the data did not follow a normal distribution in the dimensions of the two questionnaires used. In order to investigate the possible correlation between fatigue and quality of life, the non-parametric Spearman correlation analysis was performed. In addition, non-parametric tests (Spearman correlation analysis, Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal Wallis test) were performed to investigate possible correlations between patients’ fatigue as well as quality of life and socio-demographic and clinical factors. Both tools used in this study showed very good reliability (Cronbach a), namely .893 for the fatigue questionnaire and .886 for the quality-of-life questionnaire. The statistical analysis was performed with the statistical program SPSS version 23.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The study involved 134 patients (71 men and 63 women) with a mean age of 63.12 ± 11.34 years. Some patients did not complete all the questions leading to missing data. Of the participants, 67.2% of them were married, 10.9% were widowed, 12.1% were unmarried, while 6.3% were divorced. Also, 59.2% of the patients lived in an urban area,21.3% in a rural area and19.5% in a semiurban area. About 10 years had passed since they were diagnosed with T2D. The mean level of Hbc was 7.28, for the blood glucose level was 147.21, for the cholesterol was 189.73, for the triglycerides was 162.12, while the HDL and LDL mean levels were 49.22 and 102.87 respectively. Of the total sample,41.9% reported smoking, while the 56.3% did not. Additionally, 31% had only completed primary school, 19% only middle school,24.7% only senior high school, 17.8% had a bachelor’s degree, 4% had a master’s degree and 2.9% had a doctorate. In addition, 66% of patients said they had hypertension, while 32.7% said they did not. As for the type of treatment, 1.7% of the patients followed only diet, 48.8% received only tablets, 16% received only insulin, 28.7% took tablets and insulin and 4.6% followed diet and exercise.

Main results in terms of fatigue

As shown in Table 1, there is a statistically significant and positive correlation between dimensions of fatigue and age, years since the diagnosis of diabetes, Hbc levels and blood glucose. In addition, there is a statistically significant and negative correlation between fatigue dimensions and height as well as the HDL levels. There were also statistically significant differences in marital status. In particular, in the physical fatigue (x2 = 11.201, df = 3, p = .022) with the widows in the first place and the married in the last one (M = 79.52) and in mental fatigue (x2 = 16.077, df = 4, p = .002) again with the widows occupying the first place (M = 126.68) compared to unmarried (M = 76.45). Furthermore, a statistically significant difference was seen between the level of education and the mental fatigue of the patients (x2 = 17.589, df = 4, p = .002) with the holders of a postgraduate degree and primary school graduates having the highest percentages (M = 106.24 and M = 103.02 respectively). The marital status also seems to play an important role in terms of the level of fatigue. The results showed statistically significant differences with married and unmarried showing the lowest rates and widows showing the highest in all dimensions of fatigue.

The results of comparing the differences between places of permanent residence showed statistically significant differences in all dimensions of fatigue, with those living in rural areas showing the highest rates. In addition, there was a statistically significant difference in the dimension of mental fatigue (x2 = 23.628, d= 10, p = .012) between different complications of diabetes. In particular, it appears that those patients who had comorbidity also showed higher rates of mental fatigue. Likewise, the Kruskal Wallis test showed that there were significant differences between the types of treatment in the dimension of physical fatigue (x2 = 15.748, df = 4, p = .004) with those who followed only diet showing the highest rates of physical fatigue (M = 130.83).

Main results in terms of QoL

As it can be seen from Table 2, there is statistically significant and negative correlation between dimensions of QoL and age, years since diagnosis of diabetes, Hbc and LDL levels, blood glucose, triglycerides and total cholesterol. In addition, there is a statistically significant and positive correlation between dimensions of QoL and height. Better QoL was also seen to married (M = 96.38, x2 = 13.822, df = 4, p = .007) and university graduates (M = 105.41, x2 = 11.605, df = 5, p = .040). Moreover, there was a statistically significant difference between the two sexes in terms of quality of life(U = 2942.3, p = .011), family (U = 3091, p = .032) and social life (U = 3111, p = .040 ), leisure activities (U = 2785.3, p = .008), journeys (U = 2788.2, p = .003), self-confidence in achieving goals (U = 2850, p = .004), motivation to achieve goals (U = 2962.5, p = .022), people’s reaction (U = 3186.5, p = .036), uncertainty about the future (U = 3065.5, p = .030), financial situation (U = 3119.5, p = .048), dependence on others (U = 2961, p = .014) and finally life conditions (U = 2900, p = .006). Particularly, male patients showed higher rates in all of the above dimensions.

Regarding to QoL and smoking, statistically significant differences were recorded in terms of present quality of life (U = 2783.5, p = .012) with non-smokers having better rates (M = 94.10) than smokers (M = 75.13). On the contrary, significant differences were found in the quality of life (U = 2880.5, p = .025) with smokers having higher levels (M = 95.54) compared to nonsmokers (M = 78.89), but also in the subscale of dependence on others (U = 2697, p = .005) with non-smokers having higher scores (M = 94.20) than smokers (M = 73.95). As the results illustrate, there were statistically significant differences in terms of hyperintensity and present quality of life (U = 2454.2, p = .006) with non-hypertensive patients scoring higher (M = 100.7) than the hypertensive ones (M = 79.33). Similarly, significant variations were found related to the uncertainty for the future (U = 2448.5, p = .006) with the hypertensive having a higher score (M = 93.74) as opposed to the non-hypertensive (M = 71.98) and to the financial situation (U = 2517, p = .010) with the non-hypertensive to be in first place (M = 98.84) in contrast to the hypertensive patients (M = 79.58). Also, statistically significant differences were noted in freedom to eat (U = 2588.5, p = .021), enjoyment of food (U = 2566, p = .016), freedom to drink (U = 2540, p = .013) with the hypertensive people scoring higher rates in all of these subscales. There were also statistically significant differences between different types of treatment in terms of financial situation (x2 = 12.710, df = 4, p = .013) and physical activity (x2 = 9.768, df = 4, p = .045) with those who were on diet and exercise to score higher (M = 125.56 and M = 112.9 respectively). However, those who only were on diet had better rates of present quality of life (M = 125.5, x2 = 13.865, df = 4, p = .008), working life (M = 127.5, x2 = 15.387, df = 4, p = .004), family life (M = 129, x2 = 10.902, df = 4, p = .028), leisure activities (M = 113.33, x2 = 12.211, df = 4, p = .016), journeys (M = 99.67, x2 = 10.364, df = 4, p = .035), dependence on others (M = 138.33, x2 = 21.617, df = 4, p <.001) and life conditions (M = 148, x2 = 11.813, df = 4, p = .019).

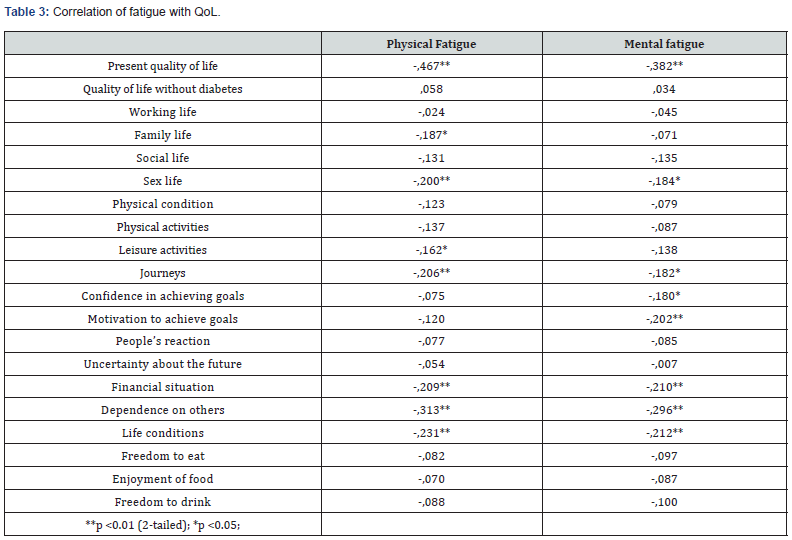

Main results in terms of QoL and fatigue

The results regarding the association of fatigue with quality of life showed statistically significant and negative correlations of all dimensions of fatigue with present quality of life, sex life, journeys, financial situation, dependence on others and life conditions. Also, there was a statistically significant and negative correlation with the dimension of family and social life, physical activity, leisure activities, self-confidence in achieving goals, motivation to achieve goals, people’s reaction, freedom and enjoyment of food (Table 3).

Discussion

The results associated with fatigue and quality of life showed negative correlations of all dimensions of fatigue with present quality of life, sex life, journeys, financial situation, dependence on others and life conditions. There was also a negative correlation with the dimension of family and social life, physical activity, leisure activities, self-confidence in achieving goals, motivation to achieve goals, people’s reaction, freedom and enjoyment of food, thus agreeing with findings from other studies [16,20]. The present finding indicates that physical and mental fatigue are not favorable factors in QoL of patients with T2D. Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between dimensions of fatigue and age as well as years since the diagnosis of diabetes, Hbc levels and blood glucose. We understand that the burden of disease along with the more years of age make patients fee more fatigued. Additionally, there was a negative correlation between fatigue dimensions and height as well as the HDL. Other factors that appear to affect fatigue levels are gender, duration of illness, presence of hypertension, marital status, place of residence, level of education, type of treatment, smoking and complications due to T2D. Relevant studies conducted in the past have indicated similar findings, such as the studies of Yeong-Mi et al. and Jain et al., which demonstrated that symptoms of hypoglycemia, disease duration and age were positively correlated with fatigue [7,13]. On the other hand, there was a negative correlation between dimensions of QoL and age, years since the diagnosis of diabetes, Hbc levels, blood glucose, LDL levels, triglycerides and total cholesterol. Also, there was a positive correlation between dimensions of QoL and height. Other factors that seemed to affect the QoL of T2D patients are gender, smoking, the presence of hypertension, marital status, level of education and type of treatment, concurring in this way with other findings [27,29]. On the whole, according to various studies diabetes affects the physical, social and psychological dimensions of QoL and more specifically work and family life something which was observed in the current research as well [19]. Also, our results meet with findings from previous research which indicated that there is a correlation between the QoL of diabetic patients and HbA1c, gender, education, marital status and social support [24-26,28].

Conclusion

Both the QoL and fatigue of such patients are affected by different sociodemographic and clinical variables. As T2D has a negative impact on the health-related QoL of patients, the goal of the state and health professionals should be the creation, development and implementation of appropriate and tailored to the needs of the population, programs that will target primarily in informing about the severity of the disease and in its prevention, but also in its management in groups that suffer in order to reduce cases on the one hand and complications on the other. The above results could be the basis for new research, focusing on additional factors that affect the QoL of this population group. Finally, in order to have the appropriate interventions that will ensure better QoL in this particular population, the constant effort and research of all scientists in the field of health is required, as new knowledge emerges through research. Regarding the limitations of the present study, it should be noted that the results obtained from this study can be further investigated in samples from other hospital settings, private or public, enabling the control of the variables under investigation and comparing the results, so that general conclusions could be drawn.

References

- (2017) International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 8th

- Kioutsouki E, Vassiliadou V (2008) Investigation of quality of life of people with type 1 diabetes. (Unpublished master’s thesis) Alexandreio Technological Educational Institution, Thessaloniki, Greece.

- Polykandrioti M, Kalogianni A (2008) The contribution of education to the control of diabetes mellitus type II. ΤΟ ΒΗΜΑ ΤΟΥ ΑΣΚΛΗΠΙΟΥ 7(2): 152-161.

- Alikari V, Fradelos E, Sachlas A, Panoutsopoulos G, Lavdaniti M, et al. (2016) Reliability and validity of the Greek version of «the Fatigue Assessment Scale». Archives of Hellenic Medicine 33(2): 231-238.

- Sharpe M, Wilks D (2002) Fatigue. Bmj 325(7362): 480-483.

- Morrison RS, Meier DE, Capello C (2003) Geriatric palliative care. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jain A, Sharma R, Choudhary PK, Yadav N, Jain G, Maanju M (2015) Study of fatigue, depression, and associated factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus in industrial workers. Industrial psychiatry journal 24(2): 179-184.

- Gawron VJ, French J, Funke D (2001) An overview of fatigue. In P. A. Hancock & P. A. Desmond (Eds.), Human factors in transportation. Stress, workload, and fatigue. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers pp. 581-595.

- Côté JN, Raymond D, Mathieu PA, Feldman AG, Levin MF (2005) Differences in multi-joint kinematic patterns of repetitive hammering in healthy, fatigued and shoulder-injured individuals. Clinical Biomechanics, 20(6): 581-590.

- Huysmans MA, Hoozemans MJ, van der Beek AJ, de Looze MP, van Dieen JH (2010) Position sense acuity of the upper extremity and tracking performance in subjects with non-specific neck and upper extremity pain and healthy controls. Journal of rehabilitation medicine 42(9): 876-883.

- Meijman TF (1997) Psychological fatigue [Mental fatigue]. Fatigue [Fatigue]. Cahiers Biosciences and Society, 19th no3. Rotterdam: Biosciences and Society Foundation p. 5-15.

- Fritschi C, Quinn L (2010) Fatigue in patients with diabetes: a review. Journal of psychosomatic research 69(1): 33-41.

- Seo YM, Hahm JR, Kim TK, Choi WH (2015) Factors affecting fatigue in patients with type II diabetes mellitus in Korea. Asian Nursing Research 9(1): 60-64.

- Hll-Briggs F, Cooper DC, Loman K, Brancati FL, Cooper LA (2003) A qualitative study of problem solving and diabetes control in type 2 diabetes self-management. The Diabetes Educator 29(6): 1018-1028.

- Singh R, Teel C, Sabus C, McGinnis P, Kluding P (2016) Fatigue in type 2 diabetes: impact on quality of life and predictors. PLoS One 11(11): e0165652.

- Koch T, Kralik D, Sonnack D (1999) Women living with type II diabetes: the intrusion of illness. Journal of Clinical Nursing 8(6): 712-722.

- Papazafiropoulos AK, Pappas SI (2014) Diabetes mellitus and quality of life. Hellenic Diabetological Chronicles 27(2): 77-83.

- Wasserman LI (2006) Diabetes mellitus as a model of psychosomatic and somatopsychic interrelationships. The Spanish journal of psychology 9(1): 75-85.

- Lyrakos G (2013) Study of the effect of fatigue in patients with diabetic neuropathy: Α clinical study. (Doctoral Thesis. Medical School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece).

- Yfantopoulos GN (2007) Measuring quality of life and the European health model. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 24(1): 6-18.

- Sapountzi-Krepia D (2004) Chronic illness and nursing care. A holistic approach.

- Pita R, Grigoriadou E, Marina E, Kouvatsou Z, Didangelos T, Karamitsos D (2006) Quality of life of patients with Diabetes Mellitus type 1. Hellenic Diabetes Chronicles 19: 282-294.

- Grandinetti A, Kaholokula JKA, Kamana’opono MC, Kenui CK, Chen R, Chang HK (2000) Relationship between depressive symptoms and diabetes among native Hawaiians. Psycho neuro endocrinology 25(3): 239-246.

- Kaholokula JKA, Haynes SN, Grandinetti A, Chang HK (2003) Biological, psychosocial, and sociodemographic variables associated with depressive symptoms in persons with type 2 diabetes. Journal of behavioral medicine 26(5): 435-458.

- Park H, Hong Y, Lee H, Ha E, Sung Y (2004) Individuals with type 2 diabetes and depressive symptoms exhibited lower adherence with self-care. Journal of clinical epidemiology 57(9): 978-984.

- Papadopoulos A, Economakis E, Kontodimopoulos N, Frydas A, Niakas D (2007) Assessment of health-related quality of life for diabetic patients type 2. Archives of Hellenic Medicine 24 (1): 66-74.

- Solli O, Stavem K, Kristiansen IS (2010) Health-related quality of life in diabetes: The associations of complications with EQ-5D scores. Health and quality of life outcomes 8(1): 18.

- Kontodimopoulos N, Pappa E, Chadjiapostolou Z, Arvanitaki E, Papadopoulos AA, et al. (2012) Comparing the sensitivity of EQ-5D, SF-6D and 15D utilities to the specific effect of diabetic complications. The European Journal of Health Economics 13(1): 111-120.

- Bakola Th (2007) Assessment of quality of life and satisfaction with treatment in patients suffering from type 2 diabetes. (Unpublished master's thesis), Hellenic Open University, Patras, Greece.

- Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL (2003) Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The Fatigue Assessment Scale. Journal of psychosomatic research 54(4): 345-352.

- Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL, Van de Vijver FJ, Sijtsma K (2004) Examination of the dimensionality of fatigue. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 20(1): 39-48.

- Zyga S, Alikari V, Sachlas A, Fradelos E, Stathoulis J, et al. (2015) Assessment of Fatigue in End Stage Renal Disease Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Medical Archives 69(6): 376-380.