Unilateral Traumatic Optic Neuropathy Case Report: A Rarity or A Pattern

Charles S Zwerling1*and Lea Carter2

1Associate Professor of Surgery, Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine

2Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Class of 2023

Submission: September 29, 2021; Published: October 07, 2021

*Corresponding author: Charles S Zwerling, Medical Director, Medical Office Place, USA

How to cite this article: Charles S Z, Lea C. Unilateral Traumatic Optic Neuropathy Case Report: A Rarity or A Pattern. Ann Rev Resear. 2021; 6(5): 555699. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2021.06.555699

Abstract

We report a case of a healthy 25-year-old Caucasian male presenting with distorted central vision of his left eye as a result of unilateral traumatic optic neuropathy. The patient was a veteran who served from 2015-to 2020. In 2017 he sustained a head injury from a motorcycle accident. All head X-rays and CT scans were normal. He required no medical treatment. His follow up neurological evaluation for TBI was considered normal. Thereafter, he developed distorted vision in his left eye. He was seen for veteran disability evaluation which uncovered a unilateral traumatic optic neuropathy of his left eye because of static visual field testing which had not been previously performed. This case may represent a potential pattern of disease for traumatic optic neuropathy. A revised management approach and awareness may benefit similar patients by selecting alternative visual field testing for suspected, optic neuropathy from trauma and/or traumatic brain injury.

Keywords: Traumatic optic neuropathy; Static visual field; Kinetic visual field; Traumatic brain injury; Veteran disability

Abbreviations: TON: Traumatic optic neuropathy; SNFL: Superficial nerve fiber layer of the retina; IOP: intraocular space with higher pressure; CSFP: cerebrospinal fluid pressure; LGN: Lateral geniculate nucleus; TBI: Traumatic brain injury

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to report an unusual case of unilateral traumatic optic neuropathy that was not diagnosed with standard kinetic visual field testing. Traumatic optic neuropathy (TON) is a form of optic nerve damage caused by either direct or indirect trauma to the head/orbit [1,2]. Indirect TON is caused by a transmission of force through the skull to the optic nerve, propagating shearing of the retinal ganglion cells [1-3]. Injury in the anterior optic nerve can cause disruption of the central retinal vessels, causing retinal hemorrhages and swelling on examination [2,3]. Injury to the posterior optic nerve commonly presents with a normal fundus examination because the retinal vessels remain intact [1,2]. Typical TON presentation includes some combination of decreased visual acuity, visual field defects, relative afferent pupillary defect in unilateral cases, and chronic optic disc atrophy [1,2,4]. TON has been classified as a relatively rare cause of trauma induced visual impairment. While only seen in 1 per million in the general population, TON has been reported to occur in 0.5-5% of closed head injuries, and up to 40-72% of traumatic brain injuries with loss of consciousness [1,3-6].

Part of a TON evaluation involves visual field testing, which proved to be a source of discrepancy in the case presented. The human visual field encompasses a maximum of 170 degrees horizontally and 130 degrees vertically [7]. Older methods of visual field testing such as the Amsler grid and tangent screen are limited to only assessing the central 30-60-degree field of vision. This limitation ultimately led to the creation of arc perimeters as a method to test the entire peripheral visual field [7,8]. The main assessment for visual fields done today is with either kinetic and/or static perimetry. Kinetic perimetry, created by Hans Goldmann, uses a moving stimulus with varying levels of intensity and size to mark the outer edge of the visual field as it comes into the patients view [8,9]. Static perimetry, commonly referred to as an automated or Humphrey Matrix, in contrast, uses a fixed stimulus with varying degrees of luminance to compare the patient’s sensitivity at each location [9]. While both perimetry methods are widely accepted, each has its uses and limitations.

Case Presentation

On 7/21/2021 a twenty-five-year-old retired veteran was examined for disability determination at Goldsboro Eye Clinic. A review of his medical records indicated that he had served in the armed forces from 2015-2020. In 2017 he sustained a head injury from a minor motorcycle accident. He was evaluated immediately after the accident at his military hospital. His head X-rays and CT scans were all negative. His vision was blurred at 20/40 OU and his eye pressures were 18 OD 17 OS. There were no facial injuries noted. The anterior and posterior segment exams were normal.

A few days later he was seen by neurology to rule out any head concussion or TBI. All neurological exam was normal. His vision had returned to normal 20/20 OU. According to the veteran, he noted after about a month, a small area of visual blurring in his left eye para-centrally. He was re-examined by optometry with best vision of 20/20 OU. There were no visual field defects noted on kinetic visual field testing according to his medical records. The veteran was denied any disability rating.

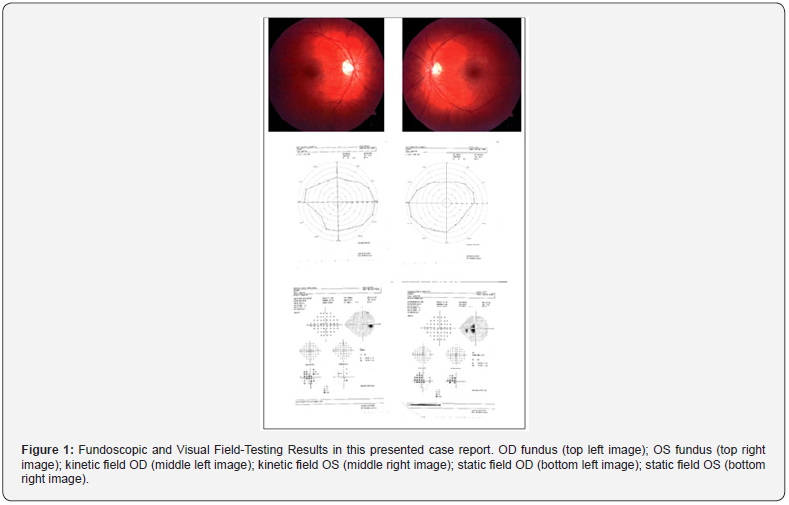

On 7/21/2021 he was seen for 2nd opinion for disability evaluation. The veteran had best corrected vision of 20/20 OU with intra-ocular eye pressures of 13 OD and 12 OS. His pupils were equally round and responsive to light and accommodation and there was no afferent pupil defect. His anterior and posterior segments exams were completely normal as well as his kinetic automated visual field (Figure 1). The veteran insisted that he had this unusual blur in his central vision of his left eye only. An Amsler Grid test was then performed, and the veteran outlined the distorted areas in his left eye. Based on his history and the Amsler Grid, a subsequent static automated visual field was ordered and revealed the temporal partial hemianopia defect of his left eye. The veteran was diagnosed with unilateral traumatic optic neuropathy of his left eye. The Humphrey field analyzer 3 was used for the assessment of this patient in this case report.

Discussion

Anatomy & physiology of optic nerve

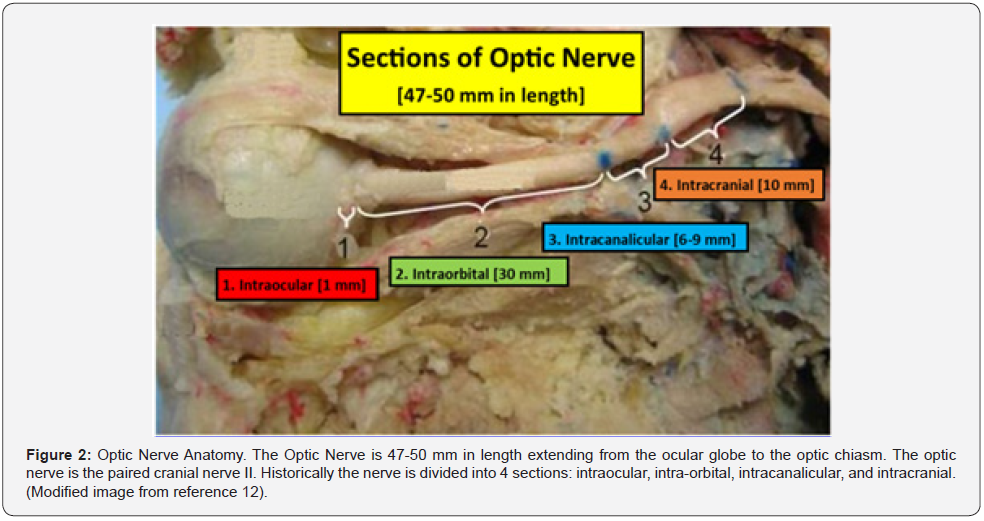

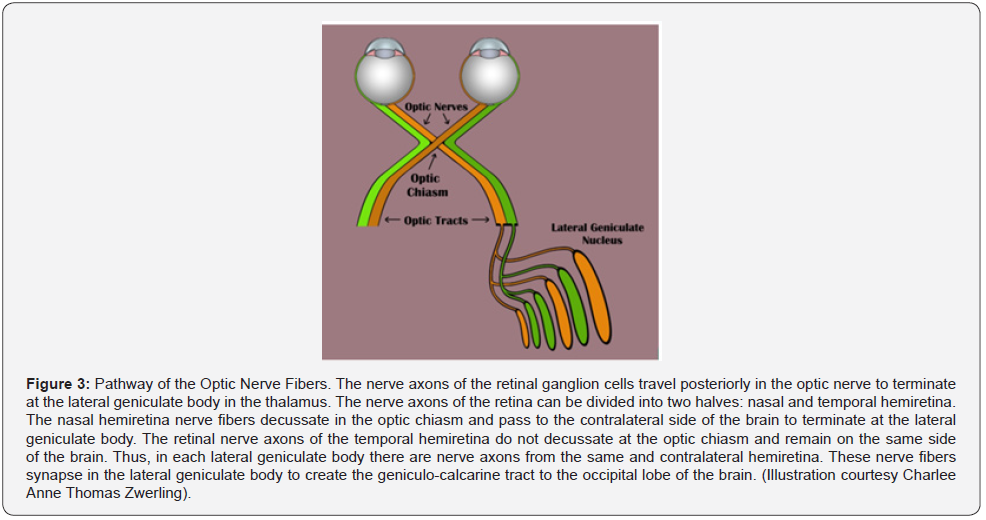

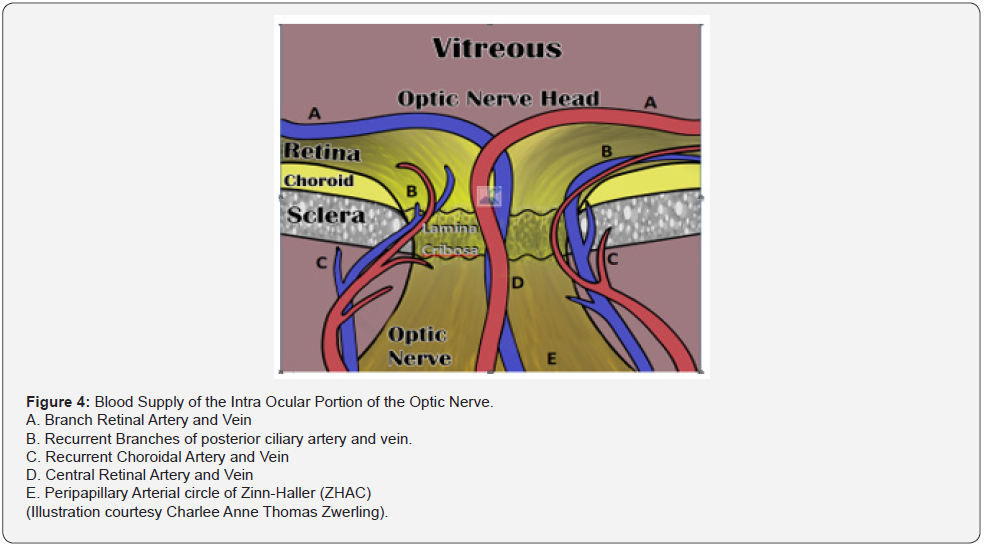

Before discussing the pathophysiology of TON, a brief review of the optic nerve anatomy would be appropriate. The optic nerve is 3-4 mm in diameter and measures 35-50 mm from the retina to the optic chiasm. The nerve is composed of intraocular (~1 mm), intra-orbital (30 mm) intracanalicular (6-9 mm), and intracranial (10 mm) segments (Figure 2) [10-12]. The axons comprising the nerve have their origin in the superficial nerve fiber layer of the retina (SNFL) and extend beyond the chiasm and optic tracts before synapsing within the lateral geniculate body [11]. From the synapse in the lateral geniculate body the 2nd order neuron extends to the occipital area of the brain where visual interpretation occurs (Figure 3). The topographic organization of the axons, as arranged by the retina, is preserved within the optic nerve. Except for its intraocular segment, the axons of the optic nerve are myelinated [10,11,13]. The optic nerve begins its formation at the optic nerve head or disc by the congruence of the superficial nerve fiber of ganglion cells (SNFL) [11].

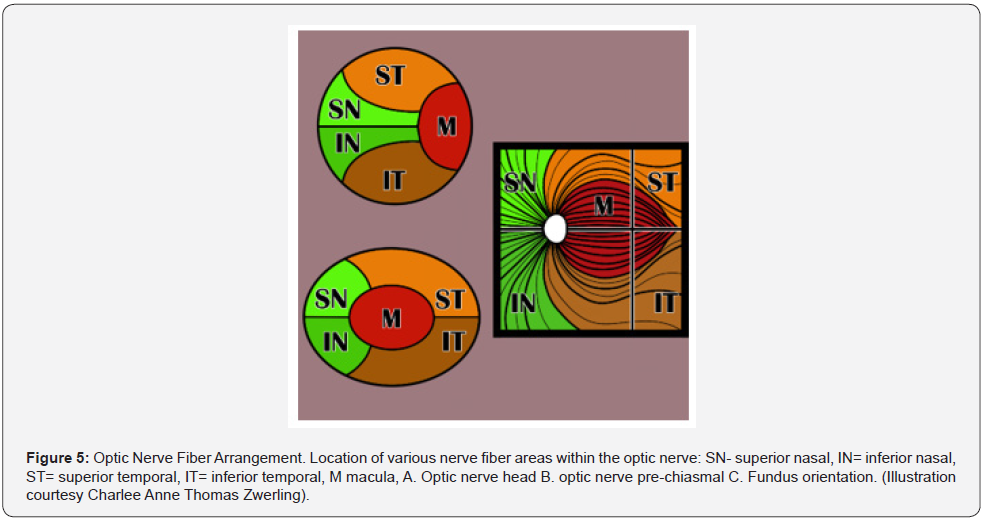

The optic disc is 1.5mm in diameter. As these neurons pass through the Lamina Cribosa, myelin sheaths are added to the exterior of the individual nerve fibers, causing the size of the optic nerve to expand to 3mm [11]. The intraocular portion of the optic nerve is divided into 4 sections: I. SNFL, II. Pre-Laminar, III. Lamina Cribrosa, and IV. Retrolaminar sections [11]. The arrangement of these fibers change as the optic nerve continues its course to the optic chiasm (Figure 4) [11]. Most of the Intraocular optic nerve axons take a direct course as they exit through the meshwork of the lamina cribosa [12,13]. However, about 10% of the axons can be diverted to pass through the cribriform pores in the central and peripheral areas of the disc. Consequently, these axons are more vulnerable to alterations of the lamina cribosa in diseases like glaucoma and traumatic optic neuropathy [11]. The lamina cribosa forms a barrier between two differentially pressurized compartments: the intraocular space with higher pressure (IOP) and the retrobulbar space with a lower pressure retrobulbar cerebrospinal fluid pressure (CSFP) [10]. From a biomechanical point of view, the lamina cribosa constitutes a weak point in the mechanical load systems, and therefore, this location is where the stress can be concentrated either from long term issues with glaucoma or short-term event from the shearing and stretching forces generated by the displacement of the lamina cribosa from trauma (Figure 5) [11].

Mechanism of TON

Direct and indirect injuries can cause TON by both mechanical and/or ischemic damage to the optic nerve. Generally, direct injuries have a worse prognosis than indirect injuries, but sometimes TON ocular injuries are so subtle there may be no external evidence [2,14,15]. Two mechanisms, primary and secondary, result in damage to the optic nerve. Primary injury occurs when mechanical shearing forces directly damage the nerve and vasculature, resulting in immediate tissue damage and irreversible loss [15-17]. Secondary injury occurs because of swelling and vasospasm, causing increased pressure that impinges axon flow within the nerve. The combined result is ischemia of the optic nerve that can lead to permanent or temporary loss of nerve function [15]. The most common site of injury of the optic nerve is the intracanalicular portion of the nerve, followed by the intracranial portion, and then the intraocular area. Deceleration injuries from motor vehicle or bicycle accidents are the primary cause of TON, accounting for 17 to 63 percent of cases [15]. Falls are the second most common cause. Optic neuropathy most commonly occurs when there is a loss of consciousness and is associated with traumatic brain injury. The role of high-dose steroids and surgical orbital decompression in treating these patients is controversial and, if administered, must be done very soon after injury [15]. Evidence for the use of these treatment modalities shows only minimal effects and is not considered a recommended treatment [15]. Post-traumatically, retinal hemorrhages, optic pallor and/or atrophy may or may not be visible on direct fundus exam depending on the location of the injury as well as its extent [15]. Evaluation of the optic nerve function has been evaluated historically by visual field testing: kinetic and static visual field analysis.

Kinetic and Static Perimetry

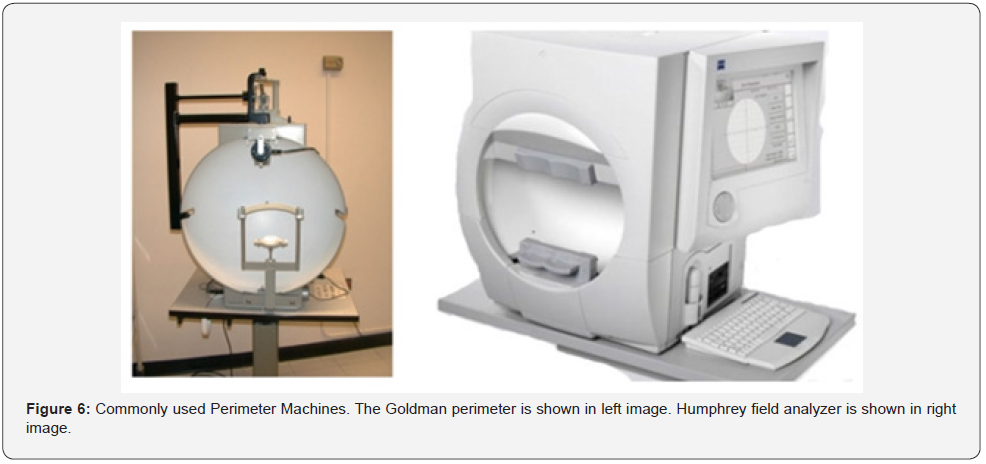

Visual field testing is an important tool in providing information about location of optic nerve damage, monitoring for disease progression, and revealing visual impairments possibly unknown to patients [2,18]. Historically, visual field testing was performed with either an automated static (Humphrey) or manual kinetic (Goldmann) technique [19,20]. Besides the difference in stimulus delivery, Goldmann perimetry was distinct from Humphrey due to the need of a trained technician. While automated Humphrey perimetry produced more reliability, Goldmann perimetry largely remained the test of choice until 2007 when the automated kinetic Octopus 900 was released [19]. In 2016, the Humphrey field analyzer 3 was announced to include both static and kinetic modes [19]. This now allowed automated modes for both static and kinetic perimetry. The Humphrey field analyzer 3 is the equipment used in the Goldsboro Eye clinic and for the assessment of the patient in this case report (Figure 6).

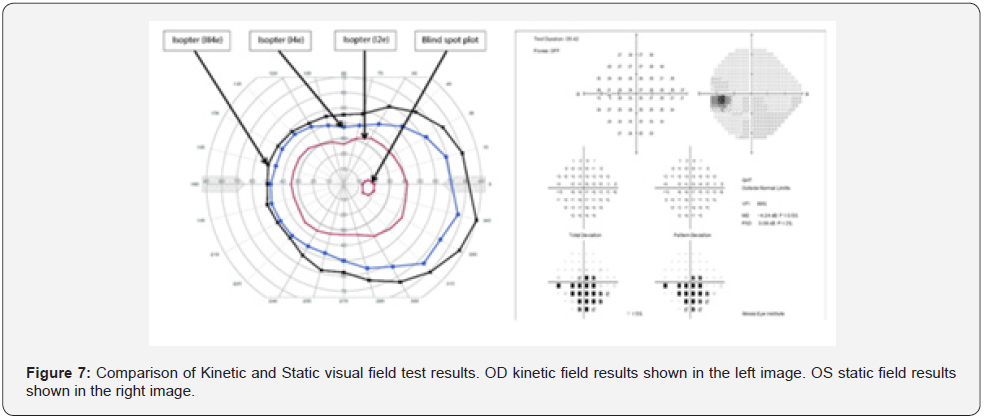

Automation of perimetry provided standardization and reduction in examiner bias, but the difference in testing mechanism still results in delivery of different outcomes. Kinetic perimetry uses various isomers of light that move into the patient’s periphery, thereby outlining the distinct shape of the visual field [20]. Static perimetry measures sensitivity to a stationary stimulus presented for 200ms, while the patient keeps their gaze centrally fixated (Figure 7) [20]. While both kinetic and static perimetry have been shown to reliably detect visual field loss, the two tests are not equal [19]. The fundamental mechanism of each test is stimulating different retinal ganglia cells [11, 21]. Motion is detected primarily through M cells in the retina ganglia layer and is projected through the magnocellular pathway to layers 1 & 2 of the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). Meanwhile, color and contrast of stationary targets is largely detected by P cells, which projects through the parvocellular pathway to layers 3&6 of the LGN [11, 22].

The moving stimulus in kinetic perimetry utilizes the corresponding magnocellular pathways, while the stationary stimulus in static perimetry is uses the parvocellular pathways [11]. Differences in visual field profiles between static and kinetic testing has long been observed and is referred to as statickinetic dissociation [21,22]. The occurrence of static-kinetic dissociation demonstrates that these perimetry techniques are not equivalent, but instead are complimentary to each other. In comparison between Goldmann/Octopus kinetic and Humphrey static analyzers, there was only an 87% match rate between devices [21]. There is even a difference between kinetic analyzers themselves. When comparing the automated Octopus and Humphrey kinetic analyzers, the Humphrey was found to have a “ceiling effect” due to the dimensions of the bowl, perpetuating missed superior and inferior field defects [19]. It has been noted in the literature that static perimetry is generally superior to kinetic in evaluating the central field of vision, while kinetic perimetry is better at evaluating the extent of the peripheral field [18,23-26]. In this case report, the patient has a central defect that was not appreciated on kinetic perimetry. A comparison study of varying neuro-ophthalmic disease found that kinetic perimetry tended to underestimate both the depth and spread of central/paracentral scotomas [27]. Another 2009 comparison showed static perimetry was able to detect small paracentral scotomas while the relative kinetic perimetry remained normal [26]. Static perimetry was 19% more sensitive for paracentral scotoma defects in this study [26].

Epidemiology

Since World War I, traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains a devastating injury for our soldiers and veterans, with rising rates due to advancements in explosives and weaponry [28]. There is a direct well-established relationship between TBI and TON. In a ten-year longitudinal study, there was a 3-time greater risk for developing TON in those with TBI when compared to a population control group [5]. Within the military, parachute jumpers specifically have a higher risk for TBI, as it is reported to be the second most common injury experienced during paratroop procedures [29]. In a self-report study at Fort Bragg, 30% of Army parachute jumpers sustained TBI’s during active duty compared to 13.5% in non-parachute soldiers [29]. Since active military and veterans are a sub-population where TON may be more prevalent, proactive assessment and proper diagnostic measures should be emphasized in post-TBI evaluation.

The variability in TON presentation makes subtle cases easy to overlook. TON often presents with sudden vision loss, but routine neurological assessment can appear normal, and may not be a sensitive tool for evaluating potential optic neuropathy. Importance should be placed on a patient’s history and symptoms when evaluating for suspected TON, even in the context of cleared neurological status. When TON occurs from damage to the posterior optic nerve, retinal examination will not display any gross abnormalities, due to the lack of retinal vasculature disruption [1,2,15]. Damage to the retinal ganglion cells is also delayed, occurring 3-6 weeks post trauma, when signs of optic disc pallor and atrophy would first be appreciated on fundus examination [5].

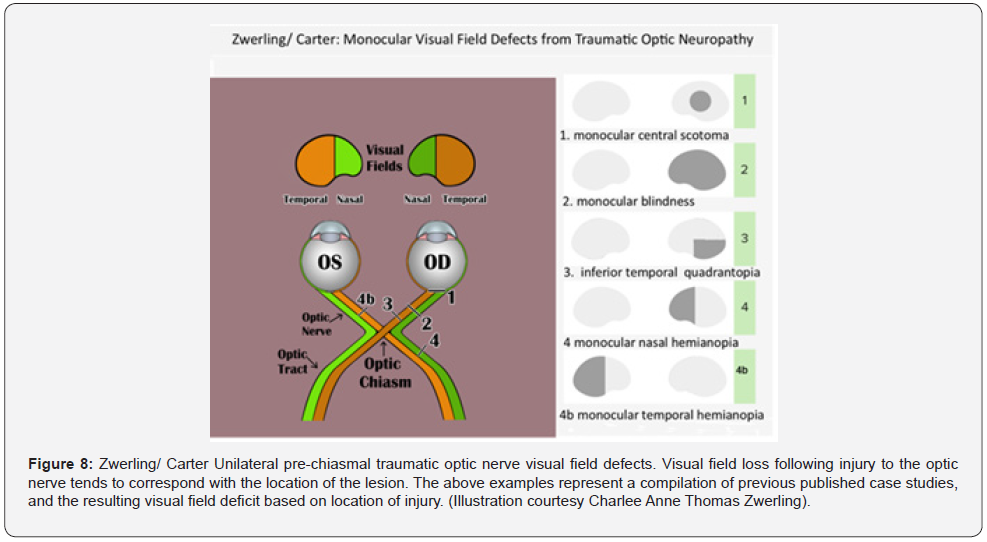

Sometimes the only indication for unilateral TON is the presence of a rapid afferent pupillary defect [1]. Due to the unpredictability in TON presentation, the protocol for TON work up includes visual acuity, color vision, visual field, RAPD testing, and fundus examination [2,16]. However, there is no pathognomonic visual field loss for TON. Visual field loss following partial avulsion of the optic nerve from the globe tends to correspond with the lesion (Figure 8) [15, 17]. In Hughes’ series, 24 patients with intracanalicular TON recovered enough vision to record a visual field. Half of these cases demonstrated an inferior altitudinal defect with macular and upper field sparing. Nerve fiber bundle defects generalized constriction and depression, as well as central and paracentral scotomas were also reported [30].

Veteran Disability Exams

The current Veteran Disability Exams require a comprehensive eye evaluation of the veteran. Visual acuity with and without best correction, Intra-ocular eye pressures, and evaluation of the anterior and posterior segments of the eye with a dilated exam. Pupil reaction to light and accommodation as well as muscle balance are observed and recorded. In addition, kinetic visual field testing is required. After recording all normal and abnormal findings a nexus is established to determine any causal relationship between military service and any documented and observed eye pathology. Any claimed condition by the veteran, because of his/her military service, is addressed by the physician. The nexus can be classified as follows: eye pathology that is Direct Service Connection, Secondary Service Connection, Aggravation of a condition that existed prior to service, or Aggravation of a nonservice connected condition by a service-connected condition. Malingering is always a concern when evaluating for disability benefits, but accurate assessment to identify true impairments should be actively pursued in all veteran disability evaluations. Veteran disability examinations require kinetic field testing but lack an indication or coverage for static field testing. Fortunately, it was not until static visual field testing was done that this veteran’s diagnosis of unilateral TON was confirmed. Visual field defects can cause serious deterioration in quality of life, including the status of a patient’s independence. Visual disability may affect the ability of an individual to take care of themselves (hygiene, cooking, cleaning) and can cause safety issues such as ability to drive a vehicle.

Evaluation Recommendations

To our knowledge, this case demonstrates a missed TON diagnosis due to the lack of static field visual field testing. A pattern of TON cases seems to be emphasized in the veteran population where TON is more prevalent and only kinetic testing is used for the visual field examination. We would recommend that veteran eye screening exams need to be amended in suspected cases of TON to include both static and kinetic visual field testing. This recommendation allows the strengths of both tests to be utilized in the evaluation of highly variable outcomes. Static perimetry has a higher sensitivity for detecting defects in the central 30 degrees of vision, while kinetic perimetry provides a better assessment of the periphery. Initiating routine use of both perimetry testing would not significantly change the cost, time, or personnel needed in workup, but could prevent a proportion of false negative results and unidentified visual disabilities.

Conclusion

We report a case of a healthy 25-year-old Caucasian male presenting with blurred distorted vision of his left eye as a result of unilateral traumatic optic neuropathy. The patient was a veteran who served from 2015-to 2020. In 2017 he sustained a head injury from a motor-cycle accident. He required no medical treatment; however, his neurological evaluation was considered normal. Thereafter, he developed distorted vision in his left eye. He was seen for veteran disability evaluation which uncovered a unilateral traumatic optic neuropathy of his left eye because of static visual field testing which had not been previously performed. Due to this potential pattern of disease, a revised management approach may benefit similar patients by selecting alternative visual field testing for suspected, optic neuropathy from trauma. Currently, the authors are using static visual field testing in a prospective trial which will be published in the near future.

References

- Saeed K, Amir A, Iman A, Toktam S, Sare S (2021) A Systematic Literature Review on Traumatic Optic Neuropathy. Journal of Ophthalmology 2021: 5553885.

- Srinivasan R, Chaitra S (2008) Traumatic Optic Neuropathy- a review. Kerala Journal of Ophthalmology 100 (1).

- Man PYW (2015) Traumatic optic neuropathy- clinical features and management issues. Taiwan Journal of Ophthalmology 5(1): 3-8.

- Lee V, Ford RL, Xing W, Bunce C, Foot B (2010) Surveillance of traumatic optic neuropathy in the UK. Eye 24(2): 240-250.

- Chen Y, Liang C, Tai M, Chang Y, Lin T, et al. (2017) Longitudinal relationship between traumatic brain injury and the risk of incident optic neuropathy: A 10-year follow-up nationally representative Taiwan survey. Oncotarget 8(49): 86924-86933.

- Steinsapir KD, Goldberg RA (1994) Traumatic Optic Neuropathy. Survey of Ophthalmology 38(6): 487-518.

- Leitman MW (2021) Manual for Eye Examination and Diagnosis. 10th John Wiley & Sons, Bronx, NY Johnson CA, Wall M, Thompson HS (2011) A history of perimetry and visual field testing. Optom Vis Sci 88(1): 8-15.

- Sample PA, Dannheim F, Artes P, Dietzsch J, Henson D, et al. (2011) Imaging and Perimetry Society Standards and Guidelines. Optom Vis Sci 88(1): 4-7.

- Crumbie L (2021) Optic Nerve.

- Salazar JJ, Ramirez AI, Hoz RD, Garcia ES, Rojas P, et al. (2018) Anatomy of the Human Optic Nerve: Structure and Function. Intech Open.

- Acharya B (2018) Anatomy of the Optic Nerve.

- Moraes CG (2013) Anatomy of the visual pathway. J Glaucoma 22(Suppl 5): 2-7.

- Guern A, Delesalle C, Borry L, Chekroun J, Gruchala C, et al. (2016) Traumatic optic neuropathy: report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Journal of Forensic Ophtalmol 39(7): 603-608.

- Hoyt WF, Miller N, Biousse V, Kerrison JB (2005) Traumatic Optic Neuropathies. In Walsh and Hoyts Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia pp. 431-447.

- Lin HL, Yen JC (2020) Acute monocular nasal hemianopia following a mild traumatic brain injury. Medicine 99(30): e21352.

- Gupta D (2021) Traumatic Optic Neuropathy. AAO Eyewiki. Traumatic Optic Neuropathy - EyeWiki (aao.org)

- Kedar S, Ghate D, Corbett JJ (2011) Visual fields in neuro-ophthalmology. Indian Journal of Ophthamol 59(2): 103-109.

- Rowe FJ, Hepworth LR, Hanna KL, Mistry M, Noonan CP (2019) Accuracy of kinetic perimetry assessment with the Humphrey 850; an exploratory comparative study. Eye 33(12): 1952-1960.

- Carroll JN (2013) Eye Rounds Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences: Visual Field Testing from one medical student to another.

- Rowe FJ, Noonan C, Manuel M (2013) Comparison of octopus semi-automated kinetic perimetry and Humphrey peripheral static perimetry in neuro-ophthalmic cases. Ophthalmol 2013: 753202.

- Phu J, Kalloniatis M, Wang H, Khuu SK (2018) Differences in Static and Kinetic Perimetry Results are Eliminated in Retinal Disease when Psychophyscial Procedures are Equated. Transl Vis Sci Technolo 7(5): 22.

- Pineles SL, Volpe NJ, Miller-Ellis E, Galetta SL, Sankar PS, et al. (2006) Automated Combined Kinetic and Static Perimetry: An Alternative to Standard Perimetry in Patients with Neuro-ophthalmic Disease and Glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 124(3): 363-369.

- Crabb DP (2015) Visual Fields. In: Glaucoma (second edition). W.B. Saunders, New York: 109-124.

- Beck RW, Bergstrom TJ, Lighter PR (1985) A clinical comparison of visual field testing with a new automated perimeter, the Humphrey Field Analyzer, and the Goldmann Perimeter. Ophthalmology 92(1): 77-82.

- Nowomiejska K, Rejdak R, Zagorski Z, Zarnowski T (2009) Comparison of static automated perimetry and static kinetic perimetry in patients with bilateral visible optic nerve drusen. Acta Ophthalmology 87(7): 801-805.

- Charlier JR, Defoort S, Rouland JF, Hache JC (1989) Comparison of automated kinetic and static visual fields in neuro-ophthalmology patient. Perimetry Update p. 3-8.

- Hussain SF, Raza Z, Cash ATG, Zampieri T, Mazzoli RA, et al. (2021) Traumatic brain injury and sight loss in military and veteran populations– a review. Military Med Res 8(42).

- Ivins BJ, Schwab KA, Warden D, Harvey S, Hoilien M, et al. (2003) Traumatic Brain Injury in U.S. Army Paratroopers: Prevalence and Character. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 55(4): 617-621.

- Steinsapir KD, Goldberg RA (2005) Traumatic Optic Neuropathy Update. Comprehensive Ophthalmology Update 6(1): 11-21.