Protecting the Frontline: An Assessment on the Occupational Factors Contributing to Covid-19 Nosocomial Infections at Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital, Zambia

Kooma EH1*, Mabuti MC2, Kalebwe V2 and Mwezi M2

1Ministry of Health, National Malaria Elimination Program, Texila American University, Zambia

2Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital [LMUTH], Occupational Health and Safety, Unit, Lusaka, Zambia

Submission: September 09, 2021; Published: October 04, 2021

*Corresponding author: Emmanuel Hakwia Kooma, Ministry of Health, National Malaria Elimination Program, Texila American University, Zambia

How to cite this article: Kooma EH, Mabuti MC, Kalebwe V, Mwezi M. Protecting the Frontline: An Assessment on the Occupational Factors Contributing to Covid-19 Nosocomial Infections at Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital, Zambia. Ann Rev Resear. 2021; 6(5): 555698. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2021.06.555698

Abstract

Background: Covid-19 pandemic has impacted the health systems in Zambia through nosocomial infections. The objective of the study was to determine the level of risks for potential occupational exposure and mitigation measures related to different jobs, work tasks and work settings.

Methods: This was an operational study that employed self-administered questionnaire and observational guide. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 and showed widespread community transmission that continued to fill up the hospital beds.

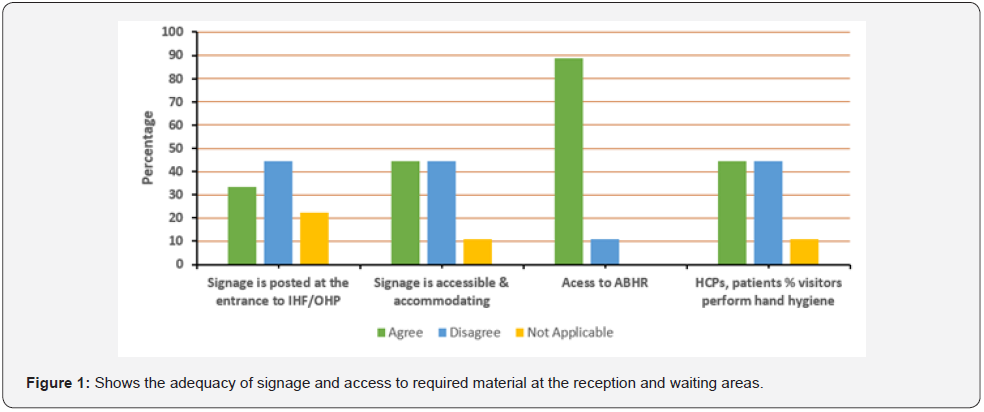

Results: The 33.3% of signage posted at the entrances to IHF/OHP and reception areas required patients and visitors to wear facemask, perform hand hygiene, maintain respiratory etiquette and promote self-identity at reception. The Assistant Health [AH] staff were aware of Covid-19 symptoms and self-monitored (100%). More than 88% of the common areas (e.g., reception and waiting room) were regularly cleaned and disinfected. About 77.8% of treatment areas, horizontal surfaces and equipment used were cleaned and disinfected before being used on another patient. The majority of Health Care Practitioners (HCPs), from travel in the 14 days from outside Zambia and Covid-19 affected areas self-monitored for symptoms and continued working with precautions. Further, most of HCPs, patients and visitors had access to alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR). Regardless of implementing the interventions, the hospital lost four members of staff: three doctors and one nurse from nosocomial infection.

Conclusion: The identified levels of risks in the occupational units further gave prioritization of highly effective mitigation measures through the hierarchy of control; engineering and administrative control than only dependence on individual behavior.

Keywords: Frontline; Contributing factors; Covid-19; Nosocomial infection; Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital; Zambia

Abbreviations: AH: Assistant Health; HCP’s: Health Care Practitioners; ABHR: Alcohol-based hand rub; OHS: Occupational Health and Safety; AMEU: Accident and Emergency Unit; PCRA: Point of care risk assessment; AGMP’s: Aerosol-Generating Medical Procedures; HVAC: Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning; IPAC: Infection prevention and control; LMUTH: Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital

Background

Everywhere in the world, health workers are at the frontline of the Covid-19 pandemic response and as such are exposed to different hazards (nosocomial infections) that make them at risk. The hospital working environment is complex and demanding and can pose significant risks to staff safety WHO [1]. Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) covers staff health, safety and welfare in the workplace. OHS is particularly important in public hospitals because major hazards exist-such as exposure to infections and chemical agents, manual handling of patients and materials, ships, trips, falls and occupational violence. These hazards can lead to Covid-19 noso-comial infections. Covid-19 was confirmed in Zambia on the 18th March,2020 with a total of 202,078 cases,193,370 (97%) recoveries and 3,521 deaths have been recorded as at 13th August, 2021 HMIS [2]. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COVI-2) pandemic has been continuing to take a heavy toll on human life spreading to new communities even as its fire appears to have dwindled somewhat in the earlier epi-centers of the country. However, the disease situation in the country has continued to improve with a further 21% reduction in positivity recorded in the past weeks prior to the first week of August 2021. In addition, daily admissions and deaths have significantly reduced over the month of July,2021 from an average of 150 to 30 and from 55 to 10 respectively HMIS [2].

Be that as it may, the Potential for health workers occupational exposure to SARS-Covid-2 could be determined by the likelihood of coming into direct, indirect or close contact with a person infected with the virus. This includes direct physical contact or care and contact with contaminated surfaces and objects. The disease transmission has been through aerosols generated from procedures on patients with COVID-19 without adequate personal protection and working with infected people, indoors, crowded places and corridors with inadequate ventilation WHO, 2020 [3], one could get the disease. The occupational exposure risk increases with the level of community transmission of SARs- Covid-2 WHO, 2020 [4]. This study describes hospital service delivery activities amidst Covid-19 pandemic during the month of January-February 2021.

Objectives of the study

a) To determine the level of risks of infection with SARs Covid-2 for potential occupational exposure related to different jobs, work tasks and work settings.

b) To assess the fitness for work environment in order to guide policies, procedures, preparedness and response planning.

c) To recommend improvements to the health and safety system in areas tasks/activities.

d) To use the results of the study to plan and implement adequate measures for risk prevention and mitigation.

Methodology

Study Design

The study was an operational case study that employed selfadministered questionnaire and observational guide to collect data. Nine respondents participated in the study. We conducted a rapid risk assessment of infection prevention and control (IPC) at the hospital using a WHO IPC tool for the employees and occupational exposure to SARs-COVID-2 for different jobs, roles and set of tasks. The approach methods were by the use of workplace risk levels: lower risk, medium risk, high risk and very high risk. The risk levels could also be useful to identify priority groups for COVID-19 vaccines deployment among health workers and others.

Study Site

The study was conducted at Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka district. The hospital was chosen for the study because it is a Covid-19 hospital that serves as referral center for other health facilities within the district. It services a population of 3,289,132 (CSO) in the high burden areas and central district of Lusaka. The Hospital has various facilities and services distributed by specialty: a 24-hour outpatient and 24 hour emergency unit, 24-hour Pharmacy, specialized clinical departments such as Internal medicine (General Medicine, Gastrointestinal endoscopy, TB and HIV clinics) Pediatrics and Child Health (General Pediatrics, TB and HIV clinics, Neonatal Vaccination),Obstetrics and Gynecology(General Obstetrics and Gynecology, Maternal and Child Health, Cervical Cancer Screening) Surgery (General Surgery, Orthopedics, Neurosurgery Ophthalmology, ENT, Urology and Dental Services) Intensive Care Service, Physiotherapy, Medical Imaging Services (CT Scan, RI, Ultra Sound, ECHO) and Laboratory. The general ICU comprises; Covid-19 IDC, Covid-19 Renal Unit, Covid-19 General Wards, Covid-19 VIP and Covid -19 Fee -Paying (HMIS/Health Plan,2021) (Picture 1).

The areas of interest assessed were:1) Reception areas 2) Screening section 3) Positive screening: providing care 4) Personal protective equipment 5) Hazard controls 6) Physical capacity/environment 7) Critical supplies and equipment 8) Human resource occupational health and safety 9) Environmental cleaning 10) Re-usable medical equipment 11) Heating, ventilation and air conditioning. Further, the IPC issues and challenges were described and initially assessed at every workplace and detailed the activities and interventions introduced to address them. We described the monitoring and evaluation methods used to assess the interventions and the analyses to determine outputs outcomes.

Data Collection Techniques

All data were collected by the researchers and selfadministered questionnaires were used to collect data from the staff of the facility. Observational guides were also used to assess the IPC practices among the health workers at the facility. In addition, a naturistic observation method was also used to create new ideas. In short, some other data were collected through observing and delivery of services. The value of observation was to permit the researchers to study the health workers in their native work environments in order to understand “things” from their perspective. Considerable time was spent in the field with the possibility of adopting various roles in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the staff being studied. Data was also collected on patient care in hospital-based settings to describe patterns of health care delivery and utilization. Settings included inpatient facilities, outpatient environments, emergency departments and administrative units. Further, the other data was from demographics and human resources, discharge status and patient identifiers (e.g., name, sex, date of birth and age). The assessment led to the prevention and mitigation measures to avoid exposure based on the level of risk, bearing in mind the hospital epidemiological situations, the specificity of the work settings and the level of adherence to IPC measures.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data that were collected were coded before being entered into SPSS version 16.0. Data was analyzed using SPSS Version 16.0. The distribution and the internal consistencies of the responses were checked. Incomplete responses were not included in the analysis.

Results

The study examined the risk of Covid-19 disease in the various occupations(units) where health workers and those in social care are at the highest risk. Ten (10) workplaces (units) were assessed. This was anticipated to guide policies to protect and support these occupations during trying period.

Reception and Waiting Area

The study in Figure 1 below, indicated that 33.3% of signage posted at the entrance to IHF/OHP and reception areas required all patients and any visitor to wear a facemask, perform hand hygiene, maintain respiratory etiquette and then report to reception to self-identify. Nonetheless, one of the participants argued that: “Signage at the entrance was not stuck for the patients and visitors to be aware”. Another experience shared by three of the study participants was that the hospital setting did not have accommodating signage: “Signage was accessible only in English language but no symbols, pictures and/or local language to accommodate everyone.” Furthermore, the study revealed that health care practitioners (HPCs), patients and visitors (more than 88%) had access to alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) hand sanitizer with 70 to 90% alcohol. In addition, it was found that alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR), tissue boxes and lined waste receptacles were available for appropriate disposal at 88.9%, 88.9% respectively while the need for the patient to wait in the waiting room was minimal.

Screening – Staff, Patients and Visitors

It was noticed that all Assistant Health (AH) staff were aware of the symptoms of Covid-19 and self-monitor (100%). Also, it was also found that most of the staff responsible for screening had access to ABHR/hand sanitizer (88.9%). In addition, three-third (66.7%) of the staff were not screened daily, including temperature checks, at the beginning of the day or shift and not recorded in a logbook. While more than fifty-five percent (55.6%) of the staff reported that there was no active screening of visitors prior to appointment. One of the participants gave a specific example of this: “The patients are screened prior to appointment but never on phone. Also, PPE was inadequate to meet the required standard for infection control.” Occupations which involve a higher degree of physical proximity to others tend to have higher Covid-19 mortality rates. The high-risk levels were rated-2: ICU, theater, endoscopy, Covid-19 wards, Dental, laboratories, Accident and Emergency Unit (AMEU). The medium risk levels were rated-2: Out-patient department standards (triage & and resuscitation), admission and filter), OPD high cost, general wards, mortuary, radiology and pharmacy. Low risk levels were rated-1: Kitchen, administration, bulk stores.

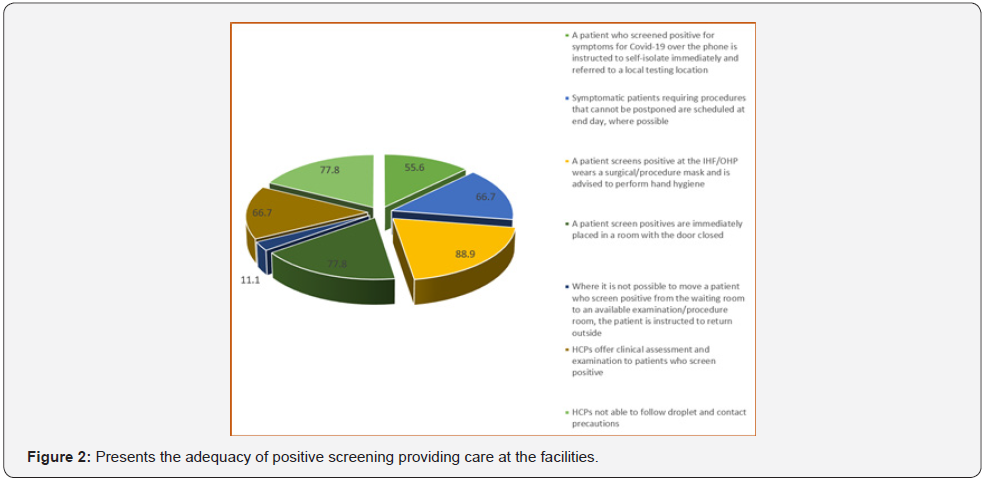

Positive Screening Providing Care

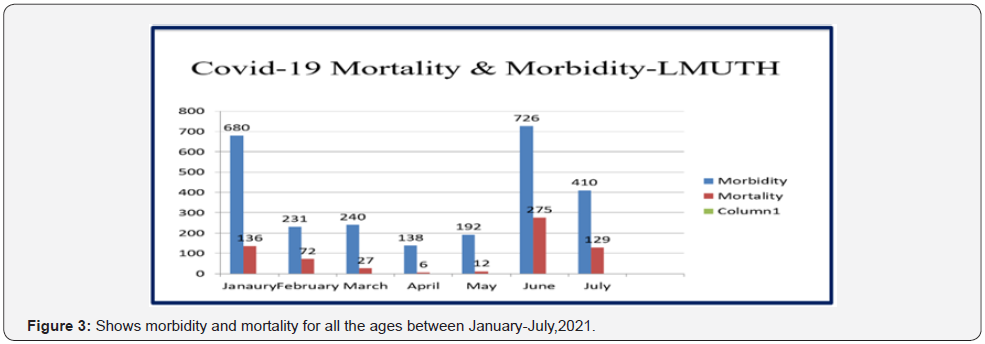

It was found that more than 55% of the patients who screened positive for symptoms for Covid-19 over the phone were instructed to self-isolate immediately and referred to a local testing location or emergency department (Figure 2). In addition, the study indicated that approximately 66.7% of symptomatic patients requiring procedures that cannot be postponed were scheduled at end of the day, where possible. However, approximately 11.1% of the patients screened positive were moved from waiting room to an available examination/procedure room; the patients were instructed to return outside (i.e., vehicle or parking lot, if available and appropriate) and informed they would be contacted when a room became available. The highest number of admissions was seen in June with 726 and 275 deaths. Followed by January with 680 Covid-19 patients and 136 deaths with 3 BIDs (Figure 3).

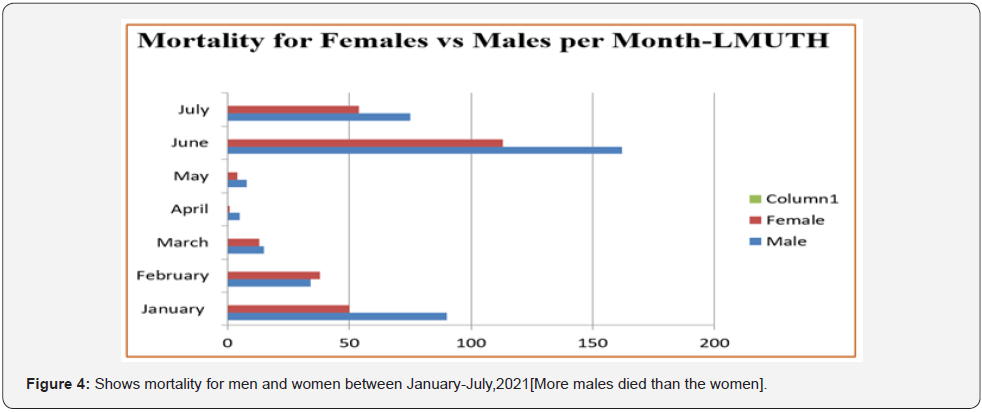

While in February there were 231 admissions with 72 hospital deaths and 5 BIDs. In March, there were 240 and 27 deaths. June had the highest number of deaths showing more males died (162) compared to females (113) in the same month. January, March, and May showed the same picture with more males dying while February had more females dying than males’ females(38) deaths while males were 34 deaths. During the first half of the year the hospital had seen a total of 533 facility deaths from Covid-19 alone out of 2,207 patients. Out of these 314 were males and 219 were females. Those that recovered were 76% over a period of 6 months and mortality was 24% over the same period. During this period the hospital lost 4 members of staff: 3 doctors and 1 nurse. All the four staff had suffered from nosocomial infection (Figure 4).

Personal Protective Equipment – PPEs

It was noticed that 55% of the HCPs did not conduct a point of care risk assessment (PCRA) before every patient interaction to determine the level of precautions required. In addition, the study indicated that PPEs, appropriate for the task to be performed, was available and easily accessible (88.9%) to the HCPs while 100% of HCPs who are required to wear PPEs had been trained in the use, care, and limitations of PPEs, including the proper sequence of donning and doffing PPEs.

Hazard Controls

The results showed that, more than 66% of the consultation, assessments and follow-ups were not conducted over the phone, video or secure messaging when possible and appropriate. Moreover, the results indicated that the number of people were minimal in 88% of the rooms during procedures and only highly experienced staff performed Aerosol-Generating Medical Procedures (AGMPs) .In addition, the results indicated that written policies and procedures for staff, patient and visitor safety including for infection prevention and control: 77% of these were easily accessible to staff.

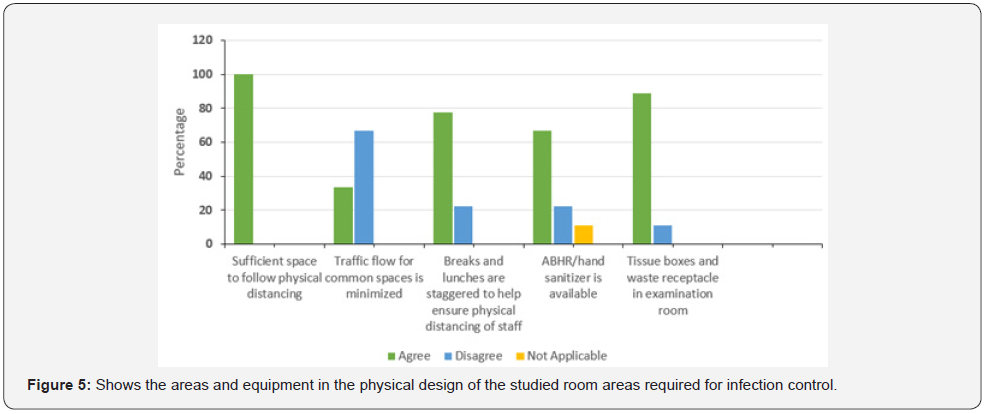

Physical Capacity/Environment

It was found that the rooms had sufficient space to follow physical distancing guidelines of maintaining at least 2 meters from other people. In addition, the result indicated high traffic flow in 66% of the common spaces (e.g., physical marking in IHF/ OHP). Furthermore, the result indicated that ABHR/hand sanitizer was 66% present in both outside and inside the examination/ procedure rooms (Figure 4).

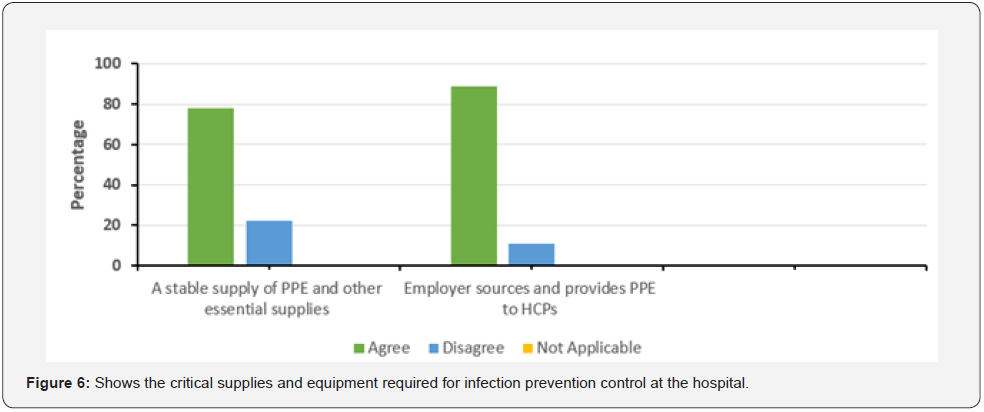

Critical Supplies and Equipment

Figure 5 below revealed that supply related to PPEs and other essential supplies were stable at 77%. Further, these results indicated that PPEs were sourced and provided in accordance with their responsibilities to ensure workplace safety under the Occupational Health and Safety Act [2011] by the employer by more than 88% (Figure 6).

Human Resources/Occupational Health and Safety

The study revealed that 66.7% of the number of staff working on site in the IHF/OHP had minimized tasks that could be done from home or outside of regular hours that would be minimize staff interactions with each other and patients. However, less than 11.1% of the HCPs who had returned from travel in the 14 days from outside Zambia, Covid-19 affected areas within or outside Lusaka and/or Covid-19 self-monitored for symptoms and continued to work with specific precautions, if they were deemed critical to operations.

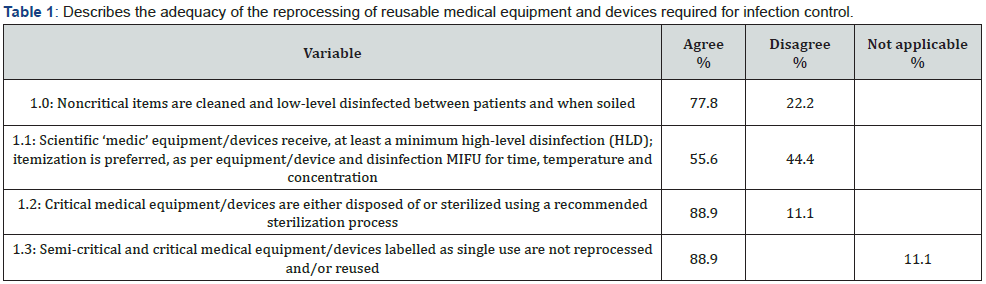

Reprocessing of Reusable Medical Equipment/Devices

It was found that non critical items were cleaned and low-level disinfected between patients and when soiled in the 77% of the studied facilities while 88% of critical medical equipment and devices were either disposed of or sterilized using a recommended sterilization process (Table 1).

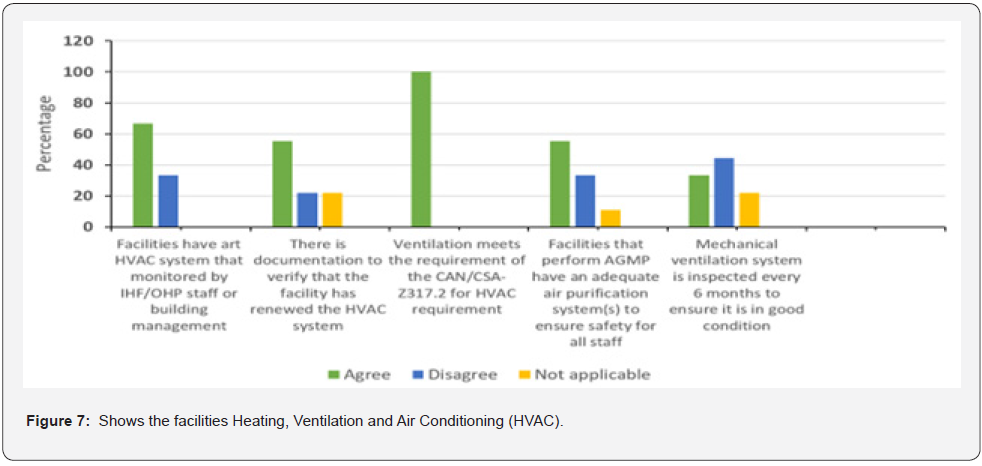

Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC)

It was found that more than sixty percent (60%) of the studied facilities had a HVAC system that was monitored by IHF/OHP staff or building management. Moreover, the table below showed that 100% of the facilities ventilation meets the requirement at 100 % of the CAN/CSA-Z317.2 for HVAC requirement. Also, the results indicated that 44% of the mechanical ventilation system was not inspected every 6 months to ensure it was in good condition (Figure 7).

Discussion

The study revealed that, the reception and waiting areas had alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR), tissue boxes and lined waste receptacles available for appropriate disposal to improve the chance of infection prevention and control. In addition, the majority of staff including HCPs that tested positive for covid-19 reported their illness either to their manager/supervisor or to the leadership/occupational health and safety officer as per usual practice. These results indicate that there is a process/policy in place for follow up of any exposures. Further, HCPs, patients and visitors (more than 88%) had access to alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR), tissue boxes and lined waste receptacles available for appropriate disposal. This finding agreed with Judith [6], who illustrated that access to alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) reduced nosocomial infections. In relation to screening, all staff were found to be aware of the symptoms of Covid-19 and self-monitored; were instructed to remain at home, or return home from work, if symptoms developed. This finding appeared seemingly due to the majority of HCPs attending training programs related to infection prevention and control. This finding agreed with Ping [7], who illustrated that, the safety or infection control training for HCPs affect in the quality-of- delivery of care to patients.

Although there has been a process to record/log all staff, patients, visitors accompanying patients and other essential visitors entering and exiting the IHF/OHP, only less than 25% of the staff, patients and visitors accompanying patients and other essential visitors were recorded in the log book. This might be due to unawareness of nurses about the importance of recording/ logging as a means of infection prevention and control. Regarding the physical capacity and the environment required for infection control, HCPs who were required to wear PPEs kit (100%) were trained in the use, care, and limitation of PPEs including the proper sequence of donning and doffing PPEs. These results contradicted with Cameron [8] who found that 55% of the health professionals responded that, they did not receive any formal training related to use of PPEs kit and its use due to reduced airborne transmission of infections www.OSHA.gov/Covid-19 [9].

Evidently, there might be a gap between knowledge and practice. HCPs might not be aware that conducting a point of care risk assessment (PCRA) before every patient interaction required to determine the level of precautions. In addition, the study revealed that the IHF/OHPs where N95 respirators were used only 11.1% of the HCPs are fit-tested at least. Further, the study illustrated that, the majority of HCPs when interacting within 2 meters with patients who screen negative and/or positive wore surgical mask/procedure mask, gloves, and performed hand hygiene before and after contact with the patient and patient environment and after the removal of PPEs. In relation to hazard controls, less than 11.1% of the consultation, assessments and follow-ups were conducted over the phone, video or secured messaging when possible and appropriate. However, the majority of the AGMS were performed in an airborne infection isolation room with the door closed, where possible. If such a room is not available, an aerosol generating medical procedure [AGMP] performed in a single room with the door closed.

Further, the hospital management provided the opportunities and resource for capacity building, and training. This finding appears to be due to the fact that staff believe about the importance of continuous learning and training in reducing and eliminating the spread of infection. The facilities were found to have sufficient space to follow physical distancing guidelines maintained at 2 meters from other people. In addition, the result indicated high traffic flow in 66% of the common spaces (e.g., physical marking in IHF/OHP). Furthermore, ABHR/hand sanitizer was 66% present in both outside and inside the examination/procedure rooms. The results are in agreement with the results of Saad [10] who stressed that, hand hygiene and hand disinfection measures control infection as the most important measures of nosocomial infection prevention and control in operating theater. Surgical personnel must strictly enforce the effective hand-scrubbing system in the scrub room. Importantly, the material and supplies of the attire required for infection prevention and control must be proper attire for the Covid-19 nosocomial infection. The PPEs and other essential supplies were stable (77%). This result is due to the fact that there was sufficient amount of googles and gowns in the hospital. Dissimilar results were found by Ahmed [11] who showed that there was inadequacy of protecting clothing in operating theatre.

In regard to the human resources/occupational health and safety required for infection control, the study revealed that the majority of staff working on site in the IHF/OHP had minimal interactions with each other. This might be due to the tasks that could be performed from home or outside regular working hours as recommended by the management. However, less than 11.1% of the HCPs, that had returned from travel in the 14 days from outside Zambia and Covid-19 affected areas within or outside Lusaka selfmonitored for symptoms and continued to work with specific precautions if they were deemed critical to operations www.cdc. gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers [12]. The majority of staff including HCPs that tested positive for Covid-19 reported their illness to their managers/supervisors or to senior management/ occupational health and safety as per usual practice. These results might be due to the fact that there has been a process/policy in place for follow up of any exposures [11-21].

In relation to environment cleaning, the IHF/OHP were found to comply with infection prevention and control (IPAC) practices for environmental cleaning. This finding appeared to be due to Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital (LMUTH) having a regular schedule for environmental cleaning in the designated reprocessing area that includes a written policy and procedures and clearly defined responsibilities. In addition, all common areas had a fixed monthly day for cleaning & disinfection of the operating room environments besides weekly and daily cleaning. Regarding the reprocessing of reusable medical equipment and devices, the majority of non-critical items were clean and lowlevel disinfected between patients and when soiled. It might be due to awareness of the HCPs about the importance of hygiene or sufficient of staff and increase in turn of the patients. Similar results found by Saad [10] stated that the majority of the operating rooms agreed about environments safety competencies between operations. Regarding the required heating, ventilation and air conditioning for infection control, the facilities had HVAC systems that were monitored by IHF/OHP staff or building management. In addition, the study facilities ventilation meets the required CAN/CSA-Z317.2 for HVAC requirement. The outcome might be due to awareness of staff and HCPs about the importance of HVAC as a means of infection prevention and control [21-32].

Conclusion

Among the many factors, the study identified levels of risks in the occupational units and showed results, that indicate the need for the prioritization of highly effective mitigation measures, through the hierarchy of controls; engineering and administrative controls than only dependence on individual behavior. The Covid-19 pandemic crisis in Zambia highlight the cardinal importance of protecting the health workforce. It has also revealed the strong interdependence between occupational health, public health and clinical policies and guidelines. Protecting the life and health of health workers is fundamental to public health response to the long-term recovery from the pandemic. To put it another way, activities for prevention and control of infection between each examination/ procedure, weekly cleaning of physical environment and caring, cleaning of air condition filters was performed by the majority of the HCPs. Given these points, a smaller number of staff were likely to be affected by the pandemic.

Further, the study recommends:

a) Develop Covid-19 risk mitigation plan by occupation and workplace [Risk level by occupation units].

b) Prepare to implement basic infection preventive measures and review continuous IPC training.

c) Develop, implement and communicate about workplace flexibilities and protections.

d) Strengthen and implement work controls (Engineering controls, Administrative Controls, Safe Workplaces and PPEs.

e) Follow existing OSHA standards (Act of 2011).

f) Classify Worker Exposure to SARs-COVI-2(Occupation Risk Pyramid for COVID-19).

g) In the long run, these recommendations will benefit LMUTH and the public at large in infection prevention and control.

References

- WHO (2020) Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic? World Health Organization, Geneva.

- (2021) The Health Management Information System (HMIS) -Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital.

- (2020) WHO Considerations for quarantine of individuals in the context of containment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Interim guidance.

- (2020) WHO Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (no) infection is suspected: Interim guidance 25 January 2020.

- (2020) WHO Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (no) infection is suspected: Interim guidance.

- Judith R, Gail A (2020) Hand hygiene for the prevention nosocomial Infections.

- Sujun Ping (2010) Nosocomial infection and control measures in the operating rooms. J Hosp Infect.

- Cameron N (2007) Growth patterns in adverse environments. Am J Hum Biol 9(5): 615-621.

- OSHA.gov/covid-19

- Saad A (2007) Developing standards of intraoperative nursing interventions for general surgery. Unpublished doctorate Thesis, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University.

- Ahmed A, Slifka MK (1996) Long-term humoral immunity against viruses: revisiting the issue of plasma cell longevity 4(10): 394-400.

- cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers

- Ahmed A (1996) Assessment of nurses’ knowledge and practices regarding universal infection control precautions of blood borne pathogens. (Unpublished) Master thesis, Alexandria University, Faculty of Nursing.

- Environmental and Modelling Group (EMG), SARS-COV-2 (2020): Transmission Routes and Environments.

- https://www.scribd.com/presentation/88098813/Hand-Hygiene:principles & practice

- Judith R, Gail A (1999) Medical surgical nursing: Total patient care 10th

- Liu Yonghua (2003) Disposable medical supplies standardized management. Journal of Hospital Infection Journal.

- Michael Marmot, Jessica Allen, Peter Goldblatt, Eleanor Herd, Joana Morrison (2020) Build Back Fairer: The COVID-19 Marmot Review.

- (2021) The Pandemic, Socioeconomic and Health Inequalities in England. London: Institute of Health Equity.

- https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020.

- https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/datasets/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritaindata/current.

- https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/datasets/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritaindata/current.

- (2020) Office for National Statistics: Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, England and Wales: deaths registered between 9 March and 28 December 2020.

- Office for National Statistics (2020): Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK.

- Public Health England, COVID-19 confirmed deaths in England (to 31 January 2021): report, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-reported-sars-cov-2-deaths.

- Saad (2007) Covid 19 HSE Analysis.

- Thanaa MA, Alaa Elden, Amna Y Saad Eid and Hand A. Eid Elsewise. General Nursing Measures Implemented for Control and Prevention of Nosocomial Infection in The General Operating Rooms.

- (2021) The Pandemic, Socioeconomic and Health Inequalities in England. London: Institute of Health Equity.

- WHO (2019) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report 43?

- https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200303-sitrep-43-covid-9.pdf?sfvrsn=2c21c09c_

- (2009) WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: first global patient safety challenge - clean care is safer care. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- https://www.who.int/publications-detail/infection-prevention-and-control-during-health-care-whennovel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125.