Hyperparathyroidism in Pregnant Women: Clinical Issues, Laboratory Findings and Relevant Therapeutic Approachesr

Rosita Fontes1,3*, Viviana Ivasiuten1, Renato Rezende Gama Veiga1, Joyce Cantoni1, Juliana Elmor Mainczyk1, Carolina Cabizuca2 and Aline Nabuco2

1Instituto Estadual de Diabetes e Endocrinologia Luiz Capriglione, Brazil

2 Hospital Federal dos Servidores do Estado, Brazil

3 Diagnosticos da America SA, Brazil

Submission: April 01, 2021; Published: April 16, 2021

*Corresponding author: Rosita Fontes, Instituto Estadual de Diabetes e Endocrinologia Luiz Capriglione, IEDE, Brazil

How to cite this article: Rosita F, Viviana I, Renato R G V, Joyce C, Juliana Elmor M, et al. Hyperparathyroidism in Pregnant Women: Clinical Issues, Laboratory Findings and Relevant Therapeutic Approaches. Ann Rev Resear. 2021; 6(3): 555690. DOI 10.19080/ARR.2021.07.555690

Abstract

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is the most common cause of hypercalcemia in outpatient settings, with an incidence in women of reproductive age of 4.7-6.2 cases per 100,000 persons. When untreated in pregnant women, PHPT can lead to maternal and fetal complications. The authors present a case of a patient with a pre-pregnancy hyperparathyroidism diagnosis: she had worsening symptoms during pregnancy, so was referred for surgery due to failure of clinical treatment to keep the disease under control. Clinical issues, laboratory findings, and relevant therapeutic approaches are discussed.

Keywords: Hyperparathyroidism; Hypercalcemia; Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome; mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy; Beta chorionic gonadotropin; Parathyroidectomy; nephrolithiasis; calciuria

Abbreviations: PHPT: Primary Hyperparathyroidism; MEN: Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Syndrome; BP: Blood Pressure; US: Ultrasound

Introduction

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a disorder that results from hypersecretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which is the most common cause of hypercalcemia in the outpatient setting. An analysis published in 2013 showed that the incidence in women of reproductive age, within a racially mixed population, is 4.7-6.2 cases per 100,000 persons [1]. In pregnant women, the disease occurs in 0.5-1.4%, and in 80% it is due to adenoma of the parathyroid glands [2]. When untreated, PHPT can lead to maternal complications such as nephrolithiasis, pancreatitis, and eclampsia, and fetal complications such as low birth weight and neonatal seizure [3-6]. Adequate control of patients who become pregnant with hyperparathyroidism can be a challenge, depending on their clinical symptoms and the laboratory and imaging evaluation. According to the trimester of pregnancy and severity of the disease, the treatment may be either clinical or surgical. The authors present a case of a patient with a pre-pregnancy diagnosis, and a worsening of symptoms during pregnancy; she was referred for surgery due to failure of clinical treatment to keep the disease under control.

Case Presentation

A pregnant 45-year-old woman, Afro-descendant, gravida 3, para 1, presented with a history of recurrent bilateral nephrolithiasis since she was 40 years old. She had a left wrist fracture after falling from height. Her past medical history was notable for low calcium intake, asthma and diabetes mellitus type 2, which was under control with metformin. In her surgical history, she underwent ureteral stent double J, and ectopic pregnancy surgery. She also suffered a lithotripsy for treatment of kidney stones. She presented for consultation for investigation of repetitive renal stones, denying any symptoms compatible with hyperparathyroidism. In her family history, there were no cases of hyperparathyroidism, no multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome (MEN), or other syndromes associated with hypercalcemia. On physical examination, the patient was overweight (BMI 28.72 kg/m2), blood pressure (BP) was 110/75 mm Hg, bone deformities or fractures were not observed, and renal fist-percussion was negative. There were no other abnormalities found.

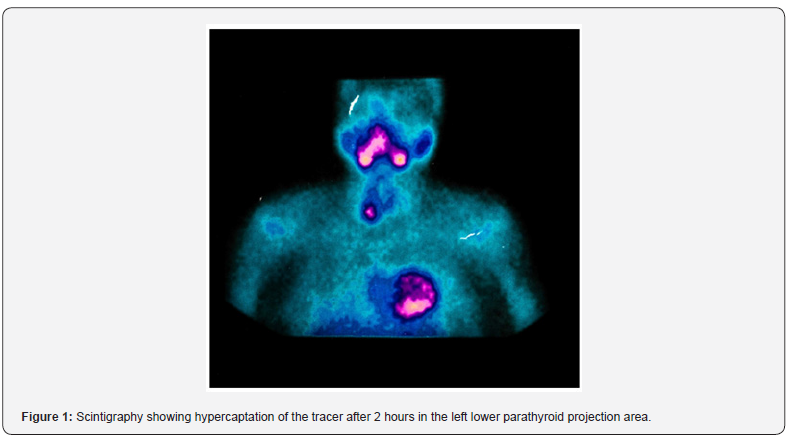

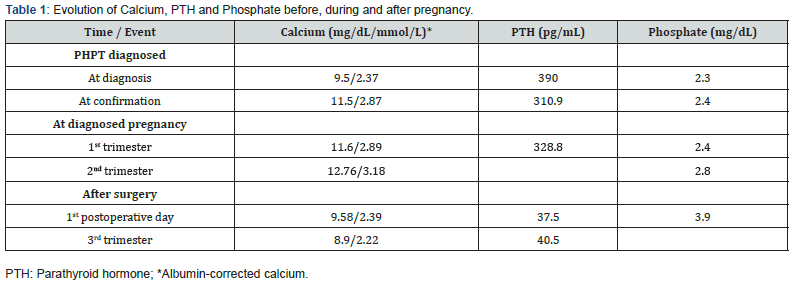

At admission, she brought examinations showing parathyroid hormone (PTH) of 390 pg/mL (12-65), total calcium corrected for albumin of 9.5 mg/dL (8.4-10.5), phosphorus of 2.3 mg/dL (2.5-4.5), as well as urinary calciuria in 24hours of 359 mg/day (100-250) and 4.78 mg/kg/day (< 4.0). Thyroid function tests were normal, as well as hemogram and biochemistry assessments. In several tests requested to confirm these results, her serum calcium was high (Table 1), along with maintained high PTH, low phosphate, and high calciuria. The parathyroid glands were not visualized on cervical ultrasound (US), but parathyroid 99mTcsestamibi scintigraphy (MIBI) showed hypercaptation of the tracer after 2 hours in the left lower parathyroid projection area, suggestive of a parathyroid adenoma (Figure 1). Renal US showed bilateral cortical stones, without lithiasis in the pyelocalyceal system. Adequate hydration and furosemide 20 mg/day were prescribed.

The 25-hydroxy vitamin D (VD) was low, 7.1 ng/mL (>30 ng/ mL), and the 1.25-dihydroxy vitamin D (1.25(OH)2D) was 193.9 pg/mL (18-78). She had recently presented with visual turbidity, nausea, headache, asthenia and dizziness, and recurrent renal colic, with an episode of pyelonephritis that was treated with antibiotic therapy. As the patient had a 2-week menstrual delay, a beta chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG) test was ordered, and the result was compatible with pregnancy. The gestational age calculated by the date of the last menstrual period was 5 weeks and 2 days. PTH and calcium remained elevated during the first trimester of pregnancy (Table 1). The option at that time, after discussion with the obstetrician, was increased furosemide at 40 mg/day and intensification of hydration. During the second trimester, the calcemia increased even more (Table 1), with the symptoms persisting. At that point, VD replacement was prescribed, and surgery was indicated. Parathyroidectomy was performed at 25 weeks of pregnancy, which was carried out without incident. On the first postoperative day, the patient had no symptoms, and the corrected calcium and PTH were normal (Table 1), although anatomopathological exam confirmed parathyroid adenoma. The pregnancy progressed without intercurrences. At 38 weeks and 2 days, she had an uneventful cesarean delivery. The newborn was healthy, with APGAR 9 at 1 minute and 10 at 5 minutes, 3.990 kg, and 49 cm, with no symptoms or laboratory evidence of hypocalcemia.

Discussion

PHPT is a rare condition in pregnancy [2,7].We present a PHPT case who became pregnant even with a diagnosis of the disease previously confirmed, and then underwent surgery for adequate hypercalcemia control. For the general population, hypercalcemia is defined as total serum calcium above 10.5 mg/ dL (>2.6 mmol/L). In a pregnant patient, the serum albumin falls due to hemodilution and remains low until delivery. Calcium is transferred through the placenta to mineralize the skeleton, and the glomerular filtration rate is increased, culminating with lower total calcium levels. Due to these factors, the upper limit of the reference range for corrected calcium in pregnancy is about 9.5 mg/ dL (2.3 mmol/L) [8,9]. This patient became pregnant at 45-yearsold. In addition to increased calcium and PTH, she presented with low phosphate and elevated 1.25(OH)2D. Most patients with PHPT are older than 50, but the disease is diagnosed during childbearing years in 25% of females [10]. Inappropriately high serum PTH concentration leads to increased renal reabsorption of calcium, phosphaturia, and 1.25(OH)2D synthesis, resulting in hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia, loss of cortical bone, hypercalciuria, and various sequelae of chronic hypercalcemia [11]. During the course of her pregnancy, the patient presented symptoms of hypercalcemia as the serum calcium increased; such symptoms do not depend on gestational age, as they are the same for non-pregnant women [6,12].

A pregnancy in a patient with hyperparathyroidism may have maternal complications of 67%, and in neonates it would be about 80% [2]. The most frequent maternal complications are hyperemesis and nephrolithiasis; less frequently, preeclampsia and pancreatitis occur [2,6]. Fetal complications may include miscarriage, neonatal seizures, low birth weight for gestational age, and hypocalcemia [3,13]. This patient and her newborn did not present complications, probably because gestation was monitored from the beginning and surgery was performed in the second trimester to control calcemia. In a normal pregnancy, PTH levels are low during the first trimester compared to nonpregnant women and remain normal through the rest of the pregnancy. The relatively low PTH may be due to the suppressive effect of raised 1.25(OH)2D [14]. In this patient with primary hyperparathyroidism, high PTH levels were due to the autonomic secretion of the adenoma, preventing its fall as calcium levels raised. As such, continuous reabsorption of calcium of the bones occurs, as well as an increase of the tubular reabsorption of calcium, including intestinal absorption secondary to 1.25(OH)2D levels [15]. This modifies what physiologically occurs in gestation, when maternal calcium falls by about 10%; the current patient presented calcium within reference values at the beginning of the investigation, which increased progressively. The therapeutic measurements in the first trimester were sufficient to maintain serum calcium at the maximum level of 11.6 mg/dL (2.89 mmol/L); however, in the second trimester, calcium increased to 12.76 mg/dL (3.18 mmol/L). The incidence of pregnancy loss and its relationship to calcium elevation is not entirely known. Fetal loss is seen at all levels of elevated maternal calcium, but it is suggested that calcium levels higher than 11.4 mg/dL (2.85 mmol/L) may increase the risk of adverse events for both mother and fetus [16].

The patient urinary calcium was already high before pregnancy, with previous nephrolitiasis. Characteristic of the gestational period is an increase of calciuria [17]. Despite increased fluid intake, the risk of new kidney stones could be high, especially because she was put on furosemide in order to control hypercalcemia, which was an additional concern in deciding on surgery. This patient had low levels of VD. It has been demonstrated that even in tropical countries, its prevalence in pregnant women may exceed 80% [18,19]. In a normal pregnancy, 1.25(OH)2D may be twice as high compared to non-pregnant women [17]. However, this patient’s 1.25(OH)2D was very high: levels of the transporter 1.25(OH)2D protein, secondary to hyperestrogenism proper to gestation, and an increase in free 1.25(OH)2D production (due to increased activity of 1 alpha hydroxylase stimulated by parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrp), estrogen, prolactin, and placental lactogen hormone) are relevant factors that contribute to this issue. In addition, the synthesis of 1.25 (OH) D is increased by the activity of placentary 1 alpha VD hydroxylation [20,21]. In this case, elevated PTH was an additional factor that increased the 1.25(OH)2Dto such high levels. We prescribed VD based on the low levels presented, since the patient would need surgical correction of the hyperparathyroidism, with 1.25 (OH) D returning to normal pregnancy levels (and thereby revealing VD deficiency). There are no specific guidelines for treatment of hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy, as the approach is individualized according to the severity of hypercalcemia, the symptoms presented, a worsening of the clinical condition, and laboratory parameters.

During pregnancy hydration, enhancement and forced diuresis are measures that can avoid severe increases in serum calcium. The medications used for this purpose are class C and D for a pregnant woman, including calcitonin, cinacalcet, and furosemide. Bisphosphonates belong to category D [5,22]. We decided to prescribe a category C drug, with furosemide being the most accessible medication for the patient. However, a 40 mg/ day dose was not sufficient to control hypercalcemia, as she had continued clinical symptoms; thus, we decided not to introduce a new medication, but to refer the patient to surgery in the second trimester. Surgery is avoided in the first trimester due to increased risk of miscarriage, and in the third trimester, due to risk of preterm birth [23]. Although uneventful surgery has been done in the third trimester [24], the second trimester is the ideal time, as it is the period with potentially lower risks for fetal complications [12,25]. The patient underwent surgery, with excision of the left inferior parathyroid at the end of the second trimester: both she and the newborn were free of complications.

Conclusion

Patients with hyperparathyroidism who become pregnant need special attention for the development of clinical symptoms, the monitoring of laboratory parameters, and appropriate therapeutic interventions, given the occurrence of certain events. Since the management of pregnant women with hyperparathyroidism is relatively limited, we present a successful case here, which is aimed at discussing its clinical aspects, expected laboratory changes, and therapeutic possibilities.

References

- Yeh MW, Ituarte PH, Zhou HC, Nishimoto S, Liu IL, et al. (2013) Incidence and prevalence of primary hyperparathyroidism in a racially mixed population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(3): 1122-1129.

- Komarowska H, Bromińska B, Luftmann B, Ruchała M (2017) Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy - a review of literature. Ginekol Polska 88(5): 270-275.

- Abood A, Vestergaard P (2014) Pregnancy outcomes in women with primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol 171(1): 69-76.

- Martínez ADH, Opazo RB, Ortega RP, Jiménez CM, Moreno MAG, et al. (2015) Primary Hyperparathyroidism in Pregnancy: A Two-Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Obstetr Gynecol 2015: 171828.

- Alharbi BA, Alqahtani MA, Hmoud M, Alhejaili EA, Badros R (2016) Preeclampsia: A Possible Complication of Primary Hyperparathyroidism. Case Rep Obstetr Gynecol pp. 7501263.

- Dale AD, Holbrook BD, Sobel L, Rappaport VJ (2017) Hyperparathyroidism in Pregnancy Leading to Pancreatitis and Preeclampsia with Severe Features. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2017: 6061313.

- Dochez V, Ducarme G (2015) Primary hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 291(2): 259-263.

- Kovacs CS, Kronenberg HM (1997) Maternal-fetal calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy, puerperium and lactation. Endocr Rev 18(6): 832-872.

- Kovacs CS (2011) Calcium and bone metabolism disorders during pregnancy and lactation. Endocrinol Metab Clin 40(4): 795-826.

- Fraser W (2009) Hyperparathyroidism. Lancet 374(9684): 145-158.

- Blaine J, Chonchol M, Levi M (2015) Renal control of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10(7): 1257-1272.

- Rey E, Jacob CE, Koolian M, Morin F (2016) Hypercalcemia in pregnancy – a multifaceted challenge: case reports and literature review. Clin Case Rep 4(10): 1001-1008.

- Korkmaz HA, Özkan B, Terek D, Dizdarer C, Arslanoğlu S (2013) Neonatal Seizure as a Manifestation of Unrecognized Maternal Hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 5(3): 206-208.

- Kovacs CS, El-Hajj FG (2006) Calcium and bone disorders during pregnancy and lactation. Endocrinol Metab Clin 35(1): 21-51.

- Madkhali TA, Chen H, Elfenbein D (2016) Primary hyperparathyroidism. Ulus Cerrahi Derg 32(1): 58-66.

- Norman J, Politz D, Politz L (2009) Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy and the effect of rising calcium on pregnancy loss: a call for earlier intervention. Clin Endocrinol 71(1): 104-109.

- Mahadevan S, Kumaravel V, Bharath R (2012) Calcium and bone disorders in pregnancy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 16(3): 358-363.

- Sachan A, Gupta R, Das V, Agarwal A, Awasthi PK, et al. (2005) High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women and their newborns in northern India. Am J Clin Nutr 81(5): 1060-1064.

- Holick MF, Bindley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, et al. (2011) Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(7): 1911-1130.

- Fleischman AR, Rosen JF, Cole J, Smith CM, DeLuca HF (1980) Maternal and fetal serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels at term. J Pediatr 97(4): 640-642.

- Turner M, Barre PE, Benjamin A, Goltzman D, Barre MG (1988) Does the maternal kidney contribute to the increased circulating 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations during pregnancy? Miner Electrolyte Metab 14(4): 246-252.

- (2018) FDA Pregnancy Categories. FDA Pregnancy Risk Information.

- Cooper MS (2011) Disorders of calcium metabolism and parathyroid disease. Best Practice Res Clin Endocrin Metab 25(6): 975-983.

- Haenel LC, Mayfield RK (2000) Primary hyperparathyroidism in a twin pregnancy and review of fetal/maternal calcium homeostasis. Am J Med Sci 319(3): 191-194.

- Walker A, Fraile JJ, Hubbard JG (2014) Parathyroidectomy in pregnancy-a single centre experience with review of evidence and proposal for treatment algorithm. Gland Surg 3(3): 158-164.