Upcoming New Drug Therapies for Nocturia - A Nonsystematic Stepwise Review

King C Lee*

Quinnipiac University, USA

Submission: January 18, 2021;Published: January 27, 2021

*Corresponding author: King C Lee, Quinnipiac University, 275 Mount Carmel Avenue, Hamden, CT 06518, USA

How to cite this article: King C L. Upcoming New Drug Therapies for Nocturia - A Nonsystematic Stepwise Review. Ann Rev Resear. 2021; 6(2): 555682. DOI 10.19080/ARR.2021.06.555682

Abstract

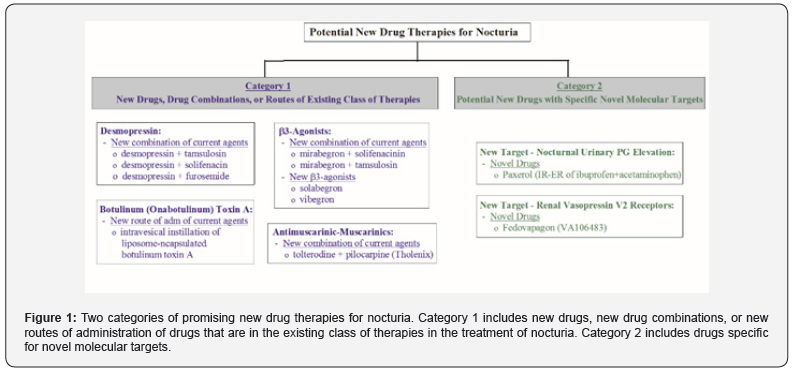

Current treatment options for nocturia are unsatisfactory, prompting review of clinical studies of potential new and better drug therapies for nocturia. A 3-step nonsystematic review was performed. Step 1 was to review articles related to nocturia in multiple databases. Step 2 was to review articles identified in Step 1 for potential new and better drug therapies for nocturia. Step 3 was to review the websites of companies sponsoring new drug therapies. Two categories of potential new drugs were identified. Category 1 drugs include new drugs, new drug combinations, or new routes of administration of drugs that are in the existing class for nocturia. They are: (a) demospressin combined with tamsulosin (an alpha-1 blocker), solifenacin (an antimuscarinic), or furosemide (a diuretic); (b) mirabegron (a β3- agonist) combined with tamsulosin or solifenacin, or new β3-agonists (solabegron and vibegron); (c) tolterodine (an antimuscarinic agent) combined with pilocarpine (a short-acting muscarinic agonist selective for salivary gland receptors); and (d) intravesical instillation of botulinum toxin A. Category 2 drugs are new drugs with novel molecular targets. They include Paxerol (prostaglandin E2 inhibitors) and Fedovapagon (a vasopressin V2 receptor agonist).

Conclusion: Category 1 potential new drug therapies have improved efficacy and/or tolerability compared to parent drugs. Due to novel molecular targets, Category 2 drugs provide additional treatment options, especially in patients who have failed current therapies, found current therapies unsatisfactory, or cannot tolerate current drug therapies.

Keywords:Nocturia; Benign prostatic hyperplasia; Overactive bladder; Lower urinary tract symptoms; drug therapy; clinical trials

Abbreviations:QOL: Quality of Life; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; BPH: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia; OAB: Overactive Bladder; LUTA: Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms; RCT: A randomized control trial; IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; PVR: Post Void Residual; EMA: European Medicines Agency; QD: Once daily; BID: Twice daily; ICSI: Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index; ICPI: Interstitial Cystitis Problem Index; ADH: anti-diuretic hormone; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; NIH: National Institute for Health; PGE2: Prostaglandin

Introduction

Nocturia

Nocturia, together with etiology, pathology, risk factors, treatment and management, are thoroughly described by Lee & Weiss [1]. Briefly, nocturia is the complaint of waking at night to void, and clinically significant nocturia is 2-3 or more nocturnal voids [1,2]. This disorder is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, negative economic implications, reduced Quality of Life (QOL) [1-7]. Etiology is multifactorial with 3 commonly known mechanistic causes: global polyuria, nocturnal polyuria, and decreased nocturnal bladder capacity [1,8].

Current Therapy of Nocturia

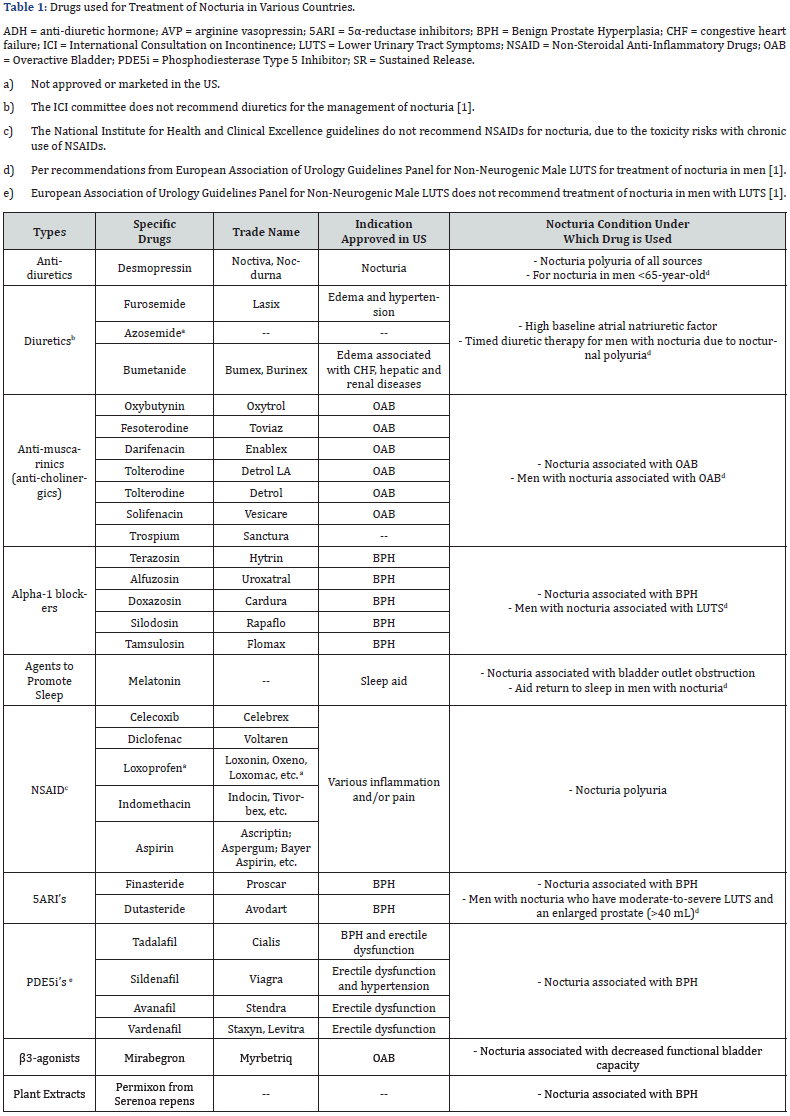

The current therapies of nocturia include lifestyle and behavioural modifications as first line therapy.1 These initial measures are cumbersome and not sufficiently effective for most patients. Pharmacological therapies are introduced after first line therapy has failed or as adjuncts in patients with sustained bother from nocturia [9]. Among all drugs currently used to treat nocturia (Table 1), desmopressin is the only drug approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for nocturia. The efficacy of desmopressin is marginal (0.2-0.4 nocturnal void reduction beyond those from placebo) and it is associated with a potentially serious adverse effect of hyponatremia. Other drugs for nocturia are off-label use, originally approved for treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), Overactive Bladder (OAB), and/or other Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) [1]. They have limited clinical studies to support their use to treat nocturia and the clinical significance of some of these drugs is questionable [1,10]. Nocturia has a poor clinical response to traditional therapies for BPH and OAB [10]. The current drug therapies for nocturia are undoubtedly unsatisfactory. This article provides an overview of clinical studies of potential promising new drug therapies for nocturia.

Materials and Methods

A 3-step nonsystematic extensive review of articles was performed. Step 1 involved review of articles that are indexed in English in the PubMed, Google Scholar, and Embase databases. Key search terms were nocturia, nocturnal voids, OAB, BPH, incontinent, clinical studies, etc. Step 2 involved review of articles on potential new drug therapies identified from Step 1. The key search terms were the generic, code and trade names of potential new drugs. Step 3 involved review of the websites of companies that sponsor the new drug therapies.

Results

Overview of promising new drug therapies The potential new drug therapies for nocturia are in two categories (Figure 1). The first category includes new drugs, new drug combinations, or new administration routes of drugs that are in the existing class of drug therapies. These new drug therapies will undoubtedly be used to treat nocturia off-label, as in the case with approved drugs for OAB, BPH and LUTS. The second category includes potential new drugs that have novel molecular targets for nocturia.

Category 1 drugs

i. Desmopressin: Desmopressin, a synthetic form of vasopressin which reduces urine production within the kidney and is provided in nasal spray (Noctiva) and sublingual tablet (Nocdurna), was approved by FDA as monotherapy for nocturnal polyuria type of nocturia [11]. Given that desmopressin has limited efficacy (0.2-0.4 nightly void reduction beyond those from placebo) and nocturia is a multifactorial medical condition in most cases [1], a drug combination treatment can provide improved efficacy and/or broaden the application for the types of nocturia [12,13]. Several combinations have been investigated, as described in subsequent sections.

ii. Desmopressin and tamsulosin combination: A randomized control trial (RCT) was conducted to evaluate the combination of desmopressin and tamsulosin (an alpha-1 blocker) to treat nocturia in patients with BPH [14]. In this clinical study, 248 patients with nocturia associated with BPH were randomized into two groups. Patients received the sublingual formulation of desmopressin (60mcg/day) and tamsulosin (0.4mg/day), or tamsulosin (0.4mg/day) only, for 3 months. The results showed that, when compared to tamsulosin alone, the combination improved nocturia and prolonged the first sleep period. International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), QOL, Post Void Residual (PVR) urine volume, and maximum urinary flow rate at night were significantly improved compared to baseline, but not between the two groups. No serious adverse effects were reported in either group.

A RCT involving the use of desmopressin as an add-on therapy to tamsulosin was conducted to evaluate the desmopressin/ tamsulosin combination in the treatment of nocturia [15]. This clinical study enrolled 216 patients with nocturia, of whom 158 (76%) had nocturnal polyuria type of nocturia, 15 (7.2%) had decreased nocturnal bladder capacity type, and 35 (16.8%) had both types, despite tamsulosin treatment for ≥4 weeks. Individually optimized dose of oral desmopressin was added while patients were still on tamsulosin, and desmopressin+tamsulosin combination was maintained for the subsequent 24 weeks. The results showed that nocturnal voids were decreased, IPSS scores were improved, and the therapy was well tolerated.

iii. Desmopressin and solifenacin combination: A RCT investigating the effect of desmopressin combined with solifenacin (an antimuscarinic) has been conducted in 68 females with OAB [16]. Patients were treated with solifenacin (5mg) alone, or solifenacin (5mg) plus desmopressin (0.2mg), for 2 weeks. The results showed that there was no difference in the time to first void between the two groups, but time to the second and third voids were improved by the combination therapy compared to solifenacin alone. The combination therapy also improved the first urgency episode and QOL scores when compared to solifenacin alone.

iv. Desmopressin and furosemide combination: A RCT was conducted in 58 elderly men and 24 elderly women with nocturia ≥2 voids/night who received furosemide at 20 mg given 6 hours before bedtime plus individually optimized dose of desmopressin, or placebo plus desmopressin, for 3 weeks [17]. The results showed that the furosemide+desmopressin combination reduced nocturnal voids and nocturnal urine volume compared to furosemide+placebo.

β3-Agonists

i. Combination with mirabegron: Mirabegron, a β3- adrenoreceptor agonist, is the only FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved product in this class and is approved for treatment of OAB. Mirabegron is also used to treat nocturia associated with OAB off-label. Two combination therapies involving mirabegron have been conducted. The first combination, mirabegron+solifenacin (antimuscarinic agent), was investigated in a RCT (the BESIDE study) involving 2,110 OAB patients who remained to be incontinent (≥1 episode during 3-day diary) following 4-week single-blind once daily (QD) of solifenacin at 5mg [18]. The patients were then randomized into 3 groups of 1:1:1 ratio and treated for 12 weeks with: (a) 5mg solifenacin, (b) 10mg solifenacin, or (c) 5mg solifenacin with 25mg mirabegron during Weeks 1-3 and then 50mg mirabegron during Weeks 4-12. The results showed that OAB symptoms (based on daily micturition, urgency, and urgency incontinence) were reduced by mirabegron, solifenacin, and mirabegron+solifenacin combination, with the greatest improvement induced by the combination. Baseline nocturia was similar among the 3 groups (1.45±0.96 voids for 5 mg solifenacin, 1.50±1.03 for 10mg solifenacin, and 1.51±1.06 for mirabegron+solifenacin). Nocturia was eliminated in 100% subjects treated with 10mg solifenacin or combination, and 99.4% subjects treated with 5mg solifenacin. There were no notable differences in adverse events (AEs) among different treatments, with the exception of dry mouth being highest with 10mg solifenacin. These results showed that mirabegron+solifenacin combination was associated with the greatest improvement in OAB symptoms. For nocturia, mirabegron+solifenacin combination and 10mg solifenacin eliminated nocturia in all subjects, whereas 5mg solifenacin in most subjects. All 3 treatments were equally safe, although 10mg solifenacin induced a higher incidence of dry mouth.

The second drug combination investigated was mirabegron+tamsulosin (an alpha-1 blocker) as an add-on therapy [19]. This study enrolled 94, with 76 completed the study, BPH patients with OAB symptoms who had been treated with tamsulosin alone for ≥8 weeks. These patients were treated with tamsulosin (0.2mg), or mirabegron (50mg) + tamsulosin (0.2mg) combination, for 8 weeks. The results showed that OAB symptoms, based on OAB symptom scores (OABSS), were improved greater in patients treated with mirabegron+tamsulosin combination than tamsulosin alone (-2.21 vs. -0.87, P=0.012). Improvements in urinary urgency, daytime frequency, IPSS, QOL index, and PVR urine volume were also greater with the combination than tamsulosin alone. Compared to baseline, nocturia (assessed based on Question 7 of IPSS) was improved by the combination (prevs. post-treatment of 2.73±1.13 vs. 2.26±1.00, P=0.001) but not tamsulosin alone (2.47±1.10 vs. 2.31±1.14, P=0.225). AEs were observed in 6 patients treated with the combination, but not in patients treated with tamsulosin. In summary, this study showed that tamsulosin+mirabegron combination was effective in patients with BPH who have OAB symptoms and nocturia after tamsulosin monotherapy [20].

New β3-agonists. Two promising new selective β3- adrenoreceptor agonists (solabegron and vibegron) are being developed for the treatment of OAB, [21,22] and will undoubtedly be used to treat nocturia off-label. These β3-agonists largely lack the side effect of dry mouth, blood pressure or heart rate, and were generally safe [22-24]. For solabegron, a Phase 2 RCT was conducted to investigate the effectiveness of 50mg Solabegron (n=88) and 125mg solabegron (n=85), when compared to placebo (n=85), given twice daily (BID) for 8 weeks in incontinent women with OAB [23]. The results showed that, when compared to placebo, 125mg (but not 50mg) Solabegron significantly and consistently improved incontinence (P=0.025), micturition, and urine volume voided. Solabegron at both doses were well tolerated, with a similar AE incidence compared to placebo. Unfortunately, nocturia was not assessed in this study. These results were confirmed by a subsequent Phase 2b RCT (the VEL- 2002 trial) in 435 women with OAB treated with Solabegron given QD for 12 weeks, according to the website and press releases by Velicept Therapeutics (the sponsor of Solabegron). For vibegron, a Phase 2a RCT in 1,395 OAB patients has been conducted to assess 3, 15, 60, or 100mg of vibegron alone, or in combination with 4mg tolterodine (an antimuscarinic agent) [25]. All doses of vibegron given alone, or in combination with tolterodine, improved OAB symptoms (micturition, urge incontinence episodes, total incontinence episodes, and urgency episodes) when compared to placebo and were well tolerated. The incidence of dry mouth was higher with combination than vibegron monotherapy. No nocturia parameters were assessed in this study.

Also, for vibegron, a 12-week Phase 3 RCT was conducted to evaluate vibegron vs. placebo in 1,232 Japanese OAB patients [24]. Patients received one of the following treatments for 12 weeks: (a) vibegron, 50 or 100mg, QD; (b) placebo; or (c) imidafenacin, an anticholinergic agent used as a positive control, 0.1mg BID. Vibegron at both doses improved OAB symptoms (micturition/ day, daily episodes of urgency, urgency incontinence, incontinence, and voided volume/micturition) and QOL, when compared to placebo. Nightly voids were reduced from baseline by -0.58 void/ night by 50 mg vibegron and -0.62 void/night by 100mg, which were greater when compared to -0.47 void/night by placebo (P=0.016 and 0.001, respectively). A subsequent post-hoc analysis on 669 patients who had ≥1 nocturnal void showed that 50 and 100mg vibegron reduced the frequency of nocturnal voiding by 0.74 and 0.78, respectively, from baselines at Week 12, which was greater than placebo (P<0.05 and 0.001, respectively) [26]. Also, the mean volume of nocturnal voids and the volume of the first nocturnal voiding were greater in vibegron groups than placebo.

The vibegron groups showed significant correlations of longer hours of undisturbed sleep with greater reduction in the frequency of nocturnal voiding and higher volume of the first nocturnal voiding. AE incidences were similar among both doses of vibegron and placebo, and all were less than imidafenacin. This study showed that vibegron was effective and safe for patients with OAB symptoms and nocturia. Two Phase 3 RCTs of vibegron are ongoing to assess vibegron (75mg) on OAB symptoms in men who are receiving pharmacological treatment for BPH and yet continue to experience OAB symptoms. One trial (the COURAGE trial) compares vibegron vs. placebo treatments, with international study sites of intended sample size of approx. 1,000 men (Trial# NCT03902080) [27]. The other trial is a singlegroup trial comparing pre- vs. post-treatment with vibegron, with multiple study sites in the US of intended sample size of 300 men (Trial# NCT04103450) [28]. Both trials assess OAB symptoms as well as nocturia. If the results from these studies are positive, they would confirm the safety and efficacy of vibegron for OAB and nocturia in men with BPH.

ii. Antimuscarinic-muscarinic combination: Antimuscurinic agents are used to treat nocturia off-label see Table 1. Tholenix is a combination of tolterodine (an antimuscarinic agent) and pilocarpine (short-acting muscarinic agonist selective for salivary gland receptors) intended to minimize dry mouth without interfering with the efficacy of the antimuscarinic. A Phase 2 RCT showed that Tholenix caused less dry mouth compared with tolterodine alone, while maintaining full efficacy in patients with OAB [29]. A Phase 3 RCT on Tholenix confirmed that Tholenix and tolterodine alone had similar efficacy, with the combination having significantly lower rate of dry mouth than tolterodine alone [30]. These studies did not assess nocturia.

iii. Intravesical instillations of botulinum (onabotulinum) Toxin A: Intradetrusor injections of botulinum toxin-A (BTX-A) have been approved for treating OAB based on several RCTs [31]. It is also used to treat nocturia off-label. Several clinical studies have been conducted to assess the efficacy of BTX-A when administered by intravesical instillation [32]. The advantage of instillation is to reduce side effects and eliminate cystoscopic needle injection to facilitate BTX-A accessing the submucosal nerve plexus. A RCT showed that single intravesical instillation of liposome-encapsulated BTX-A decreases OAB symptoms [33]. This study did not access the treatment effect on nocturia.

Another study was conducted to assess the feasibility and safety of a mixture of TC-3 gel (a novel reverse-thermal gelation hydrogel) and BTX-A for the treatment of interstitial cystitis bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) administered by instillation. This study was conducted in 15 severely symptomatic patients who had Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index (ICSI) and Interstitial Cystitis Problem Index (ICPI) scores ranged 12-19 and 12-16, respectively, and median Visual Analog Scale (VAS, for pain assessment) being 7. After instilled into the bladder as liquid, TC-3 gel/BTX-A mixture solidified because of body heat, and gradually dissolved to release BTX-A into the bladder over several hours via sustained release. The results showed that there was no increase in VAS score between pre- vs. post-treatment values (6.6±2.7 vs 5.3±2.8, P=0.044). All AEs were transient and mild, with the most common being temporary mild constipation (n=4, 26%). Mean ICSI and ICPI scores were reduced compared with baseline (15.4±2.4 vs. 12.9±4.3, and 14.8±1.4 vs. 11.9±4.0, both P=0.004). Compared to baselines, nocturia was decreased at Week 6 (3.3±2.1 vs. 1.8±0.9, P=0.046) and returned to baseline level at Week 12. The results indicated that intravesical instillation of a TC-3 gel/BTX-A mixture is effective, safe and tolerable for IC/BPS, and provided temporary relief of nocturia lasting for a few weeks.

Category 2 - drugs with novel molecular targets for treatment of nocturia

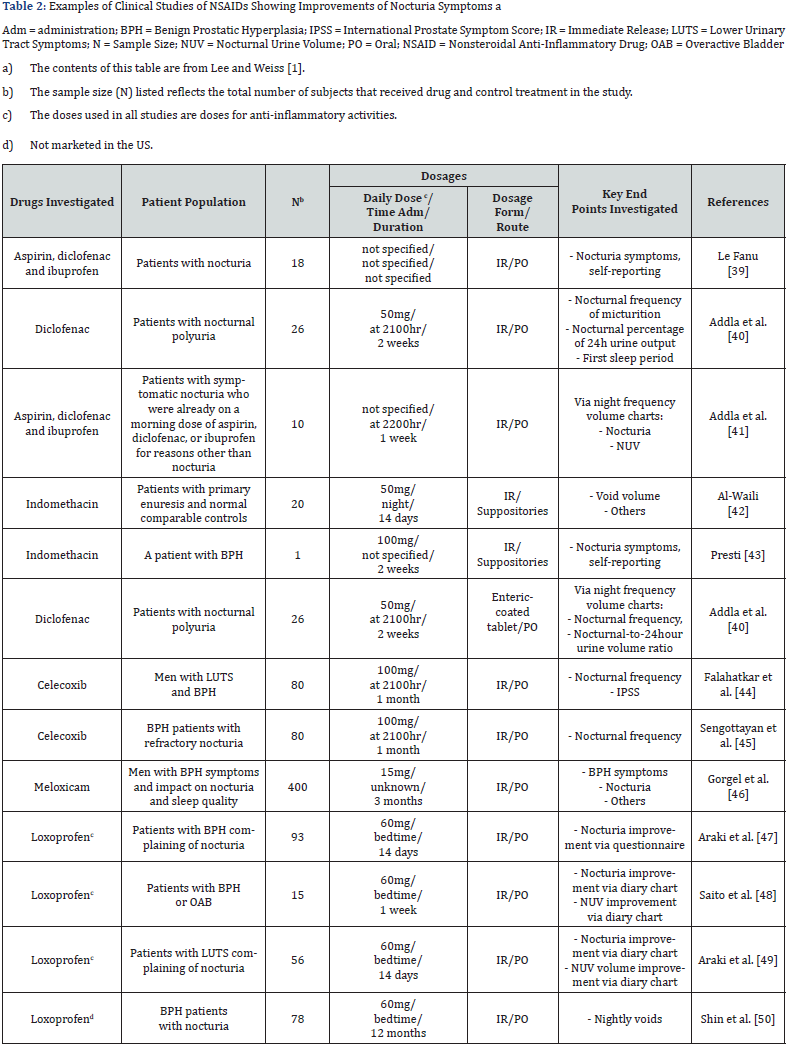

i. Urinary prostaglandin: Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is involved in the pathogenesis of nocturia, via inhibition of the hypothalamic anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) in the kidney which causes increases in urinary output and local modulation of reflex micturition in the bladder. ADH and PGE2 normally regulate the production of each other, thus keeping a fine balance of fluid hemostasis [34-36]. Urinary prostaglandin levels follow a circadian rhythm [37,38], and elevated urinary PGE2 levels occurred in patients with voiding diseases. Abnormal PGE2 levels at night occurred in patients with OAB [39,40]. Because of prostaglandins’ involvement in local modulation of reflex micturition and pathogenesis of nocturia, anti-prostaglandin agents should provide benefits in the treatment of nocturia. Indeed, various clinical studies have shown that Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), which are prostaglandin inhibitors, can improve nocturia symptoms (Table 2). All clinical studies were conducted using anti-inflammatory doses, which are several factors higher than those needed for urinary PGE2 inhibition. The presumption for the need of high or anti-inflammatory dose levels for antinocturia activities is understandable, as the role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of diseases associated with nocturia has been described [41,42].

Chronic use of NSAIDs at high or anti-inflammatory doses is associated with toxicity risk, including increase risk of cardiovascular and gastrointestinal toxicities, and risk of hepatotoxicity secondary to inadvertent overdose with acetaminophen (a prostaglandin inhibitor similar to NSAIDs). The National Institute for Health (NIH) and Clinical Excellence guidelines do not recommend the use of NSAIDs for treatment of nocturia. Paxerol is a novel proprietary immediate release/ sustained release (50%:50%) formulation of the prostaglandin inhibitors, acetaminophen and ibuprofen [43]. One-half of a Paxerol tablet is released via immediate release during the first hour to provide “loading dose” effect, whereas the other half is released via sustained release for up to 6 hours to coincide with the normal 6-8 hours of sleep. Paxerol is a low dose package form, with each tablet containing 325mg acetaminophen and 150mg ibuprofen. This is ~50% and ~12.5%, respectively, of the lowest daily anti-inflammatory dosages, and ~33% and ~5%, respectively, of maximum Over the Counter (OTC) daily doses. The amounts of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in each Paxerol tablet correspond to the lowest concentrations for maximum inhibitory effects of bladder smooth muscle contractions induced by lipopolysaccharide of Salmonella typhimurium in vitro (unpublished data). Furthermore, acetaminophen is a selective COX-2 inhibitor.

It is synergistic with ibuprofen in the inhibition prostaglandin production at the peroxidase (POX) site within COX-1/2 enzymes [44,45] and synergistic for the analgesic effects in humans [46,47]. Due to synergism, the use of low doses of ibuprofen and acetaminophen can maximize the efficacy for nocturia yet reduces the toxicity risks associated with long-term use. This is indeed the case, as demonstrated in a Phase 2 RCT of Paxerol in 86 patients with severe nocturia (≥2.5 nightly voids) associated with OAB [43] receiving one, two, or three Paxerol tablets per day for 14 days, or placebo. The 3 doses of Paxerol equally reduced nocturia when compared placebo. Percent of patients with an average baseline nocturnal void frequency of 3.6±1.0 episodes reduced to 0 or 1 void for ≤1 night were greater with the Paxerol groups than the placebo group. Also, ~35% of patients in this trial had BPH, as OAB and BPH are not exclusive etiologies. Subgroup analysis indicated that Paxerol appears to be equi-effective for those with and without BPH. There were no treatment related AEs in any groups. Note that although safety and broad efficacy were demonstrated, this Phase 2 RCT was a short-term study with limited sample size of 86. Further dose-response studies with larger sample size and for longer treatment duration are needed to validate the efficacy and safety of Paxerol to treat nocturia.

ii. Renal vasopressin V2 receptor: Fedovapagon, a vasopressin V2 receptor agonist, is a novel small molecule investigational drug for the treatment of nocturia. Fedovapagon induces antidiuretic effect by activating the vasopressin V2 receptors in the collecting ducts of the kidney. Activation of the V2 receptors causes the kidneys to reabsorb water from urine as it passes toward the bladder. Dosing of fedovapagon before bedtime leads to less urine produced overnight. Clinical studies showed that fedovapagon induced dose-dependent reductions in nighttime urine production and urine volumes. Fedovapagon has a longer half-life than desmopressin, which may make the drug more likely to result in prolonged antidiuresis at nighttime compared with desmopressin but could result in a higher risk of hyponatremia.

A Phase 2/3 RCT (the EQUINOC trial) in 432 patients with BPH and nocturia has been conducted [48,49]. Patients received PO fedovapagon (2 mg) or placebo each evening over 12 weeks. When compared to placebo, fedovapagon improved nocturnal voids from baseline (p=0.004). There were also improvements in time to first void (p<0.001), nights when patients had 0 or 1 voids (p=0.038), and patients who reduced nightly voids by 50% (P=0.007). Fedovapagon was generally well tolerated. This study indicated that Fedovapagon may be an effective treatment for BPH and nocturia. A second Phase 3 study based on the same endpoints and patient population is ongoing. The goal is to provide additional data required to support regulatory filings for marketing approval.

Discussion and Conclusion

Clinical studies of two categories of potential new drug therapies for nocturia are described in this review article. Category 1 drugs are new drugs, new drug combinations, or new administration routes of drugs that are in the existing class of drug therapies for nocturia see Table 1. They improved efficacy, safety or tolerability. β3-Adrenoreceptor agonists were one type of Category 1 drug therapies. Mirabegron is currently the only FDA and EMA approved drug in this class, with the approved indication for treatment of OAB. Their use to treat nocturia associated with OAB is off label. There are recent clinical studies of three new β3- adrenoreceptor agonists (solabegron, vibegron and ritobegron). The β3-agonists largely lack the side effects of dry mouth, had no risk for blood pressure or heart rate increase, and were generally safe [22-24]. This review article describes only solabegron and vibegron. For ritobegron (KUC-7483), only Phase 1 trial data were published [50]. The Phase 2 and Phase 3 RCTs (Study Nos. NCT00742833 and NCT01003405, respectively) [51,52] for assessments of OAB are listed as “COMPLETED” in clinicaltrials. gov. Another Phase 3 RCT (Study No. NCT01003415) [53], also for assessment of OAB, is listed as “WITHDRAWN”. Data from these Phase 2 and 3 RCTs were not published. On the website of the sponsor (Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd), the first Phase 3 trial was once labeled as having failed to reach its primary endpoint and the program has been put on hold [54].

The sponsor might have terminated clinical development of this product. Also, emerging pharmacovigilance data on mirabegron have identified a rare risk for excessive hypertension, thus are contraindicated in patients with severe hypertension [55]. The excessive hypertensive effect of mirabegron is not related to activation of cardiac β3-adrenoceptors, as the human heart lacks functional β3-adrenoceptors [56], but may be due to β1-adrenoceptor medicated positive inotropic effects on human atrium [57]. It is unknown if the new selective β3-agonists also induce the rare severe hypertension. Another type of Category 1 drug therapy is the antimuscarinic/muscarinic combination. Tholenix is a combination of tolterodine (an antimuscarinic agent) and pilocarpine (a short-acting muscarinic agonist with selectivity for salivary gland receptors) for countering the dry mouth without interfering with the efficacy of the antimuscarinic. Phase 2 and 3 RCTs showed that Tholenix caused less dry mouth compared with tolterodine alone, while maintaining full efficacy on OAB symptoms [29,30]. These studies did not assess nocturia. However, clinical studies have shown that tolterodine alone, though effective for OAB, is not effective for nocturia [1,58]. Therefore, tolterodine+pilocarpine combination is unlikely to be effective for nocturia.

Category 2 drugs are those with novel molecular targets. These drug therapies can provide additional treatment options, especially in patients who have failed current therapies, found current therapies unsatisfactory, or cannot tolerate current drug therapies. Two investigational drugs (Paxerol and fedovapagon) were described in the current article, both with promising clinical trial results. Paxerol has a novel proprietary immediate release/ sustained release (50%:50%) formulation of the prostaglandin inhibitors, acetaminophen and ibuprofen [43]. As expected, Paxerol is safety and well tolerated, due to the doses of the prostaglandin inhibitors being a fraction of OTC doses used for anti-inflammatory and analgesic indications. Paxerol’s nocturia efficacy is broad, encompassing males and females with OAB and/ or PBH. This is also expected as its site of action is “downstream”, located in the bladder. However, Paxerol’s clinical data are from a short-term Phase 2 RCTs with limited sample size of 86. Further RCTs are needed. The second potential drug therapy with a novel molecular target is fedovapagon, a potent vasopressin V2 receptor agonist. The second Phase 3 study in patients with nocturia is ongoing and is needed to support regulatory filings for marketing approval. Fedovapagon induces antidiuresis at nighttime which can lead to hyponatremia, as in the case with desmopressin. This potential AE is being carefully monitored in the ongoing Phase 3 trial [59-72].

Summary and Conclusion

There are a number of potential new drug therapies for nocturia. One category includes the new drugs, new drug combinations, or new administration routes of drugs that are in the existing class of drug therapies for nocturia. Category 1 drug therapies frequently resulted in improvement of efficacy and/or tolerability. The second category of potential new therapies has novel molecular targets. Category 2 drugs can provide additional treatment options, especially in patients who have failed current therapies, found current therapies unsatisfactory, or cannot tolerate current drug therapies. The Category 2 drugs include Paxerol (a combination of PGE2 inhibitors) and fedovapagon (a vasopressin V2 receptor agonist).

References

- Lee K, Weiss J (2019) Nocturia: Etiology, Pathology, Risk Factors, Treatment and Emerging New Therapies. In: Masucci S (Ed.), (1st edn), Elsevier.

- Bosch JLH, Weiss JP (2013) The Prevalence and Causes of Nocturia. J Urol 189(1): S86-S92.

- Coyne KS, Zhou Z, Bhattacharyya SK, Thompson CL, Dhawan R, et al (2003) The prevalence of nocturia and its effect on health related QOL and sleep in a community sample in the USA. BJU Int 92(9): 948-954.

- HolmLarsen T (2014)The economic impact of nocturia. NeurourolUrody 33(Suppl1): S10-S14.

- Kupelian V, Fitzgerald MP, Kaplan SA, Norgaard JP, Chiu GR, et al (2011) Association of nocturia and mortality: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.J Urol 185(2): 571577.

- Tikkinen KA, Johnson TM, Tammela TL(2010) Nocturia frequency, bother, and quality of life: how often is too often?A population-based study in Finland. Eur Urol 57(3): 488-496.

- Weiss JP (2012) Introduction. In: Weiss JP, Blaivas JG, Van Kerrebroeck PEV, Wein AJ, (Eds.), Nocturia. (1stedn), Springer, New York, USA,p. 1.

- Bosch JL, Weiss JP (2010) The prevalence and causes of nocturia.J Urol 184(2): 440-446.

- Oelke, M, De Wachter S, Drake MJ (2017) A practical approach to the management of nocturia. Int J Clin Pract 71(11): e13027.

- Smith AL, Wein AJ (2011) Outcomes of pharmacological management of nocturia with non-antidiuretic agents: does statistically significant equal clinically significant?BJU Int 107: 1550-1554.

- (2019) Desmopressin Acetate Monograph.

- Rao VN, Gopalakrishnan G, Saxena A, Pathak H, Dalela D, et al. (2016) Nocturia – Symptom or a Disease?J Assoc Physicians India 64(11): 56-63.

- Yazici CM, Kurt O (2015) Combination therapies for the management of nocturia and its comorbidities. Res Rep Urol7: 57-63.

- Ahmed AF, Maarouf A, Shalaby E (2015) The impact of adding low-dose oral desmopressin therapy to tamsulosin therapy for treatment of nocturia owing to benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Urol 33(5): 649-657.

- Bae WJ, Bae JH, Kim, SW(2013) Desmopressin add-on therapy for refractory nocturia in men receiving alpha-1 blockers for lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol 190(1): 180-186.

- Han YK, Lee WK, Lee S (2011) Effect of desmopressin with anticholinergics in female patients with overactive bladder. Korean J Urol 52(6): 396-400.

- Fu FG, Lavery HJ, Wu DL (2011) Reducing nocturia in the elderly: A randomized placebo-controlled trial of staggered furosemide and desmopressin. NeurourolUrodyn 30(3): 437.

- Gibson W, MacDiarmid S, HuangM, Siddiqui E, Stolzel M, et al. (2011) Treating overactive bladder in older patients with a combination of mirabegron and solifenacin: a prespecified analysis from the BESIDE study. Eur Urol Focus 3(6): 629-638.

- Ichihara K, Masumori N, Fukuta F, Tsukamoto T, Iwasawa A, et al. (2015) A randomized controlled study of the efficacy of tamsulosin monotherapy and its combination with mirabegron for overactive bladder induced by benign prostatic obstruction. J Urol 193(3): 921-962.

- Edmondson SD, Zhu C, Kar NF, Di Salvo J, Nagabukuro H,et al. (2016) Discovery of vibegron: a potent and selective β3 adrenergic receptor agonist for the treatment of overactive bladder. J Med Chem 59(2): 609-623.

- Ellsworth P, Fantasia J (2015) Solabegron: a potential future addition to the β-3 adrenoceptor agonist armamentarium for the management of overactive bladder. Expert OpinInvestig Drugs 24(3): 413-419.

- Michel MC, Gravas S (2016) Safety and tolerability of β3-adrenoceptor agonists in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome - insight from transcriptosome and experimental studies. Expert Opin Drug Saf 15(5): 647-657.

- Ohlstein EH, von Keitz A, Michel MC (2012) A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist solabegron for overactive bladder. Eur Urol 62(5): 834-840.

- Yoshida M, Takeda M, Gotoh M (2018) Vibegron, a novel potent and selective β3-adrenoreceptor agonist, for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Eur Urol 73(5): 783-790.

- Mitcheson HD, Samanta S, Muldowney K, Pinto CA, de A Rocha B, et al. (2019) Vibegron (RVT-901/MK-4618/KRP-114V) Administered Once Daily as Monotherapy or Concomitantly with Tolterodine in Patients with an Overactive Bladder: A Multicenter, Phase IIb, Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Trial.Euro Urol 75(2): 274-282.

- Yoshida M, Takeda M, Gotoh M, Yokoyama O, Kakizaki H, et al. (2019) Efficacy of novel β3-adrenoreceptor agonist vibegron on nocturia in patients with overactive bladder: A post-hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Int Jour of Urol 26(3): 369-375.

- (2019) Study No. NCT03902080:Study to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Vibegron in Men with Overactive Bladder (OAB) Symptoms on Pharmacological Therapy for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH).

- (2019) Study No. NCT04103450:Extension Study of Vibegron in Men with Overactive Bladder (OAB) Symptoms on Pharmacological Therapy for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH).

- Dmochowski RR, Staskin DR, Duchin K(2014) Clinical safety, tolerability and efficacy of combination tolterodine/pilocarpine in patients with overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pract 68(8): 986-994.

- Lee K, Ko KJ, Yoon SJ, et al. (2017) Efficacy and safety of combination of tolterodine and pilocarpine in overactive bladder patients: a randomized double-blind multicenter phase 3 study. NeurourolUrodyn 36(Suppl 3): S45.

- Cruz F, NittiV (2014) Chapter 5: clinical data in neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO) and overactive bladder (OAB). NeurourolUrodyn 33(Suppl3): S26-S31.

- Lee HY, Seung WD, Yang WJ (2019a) Efficacy and Safety of Noninvasive Intravesical Instillation of Onabotulinum Toxin-A for Overactive Bladder and Interstitial cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Urology 125: 50-57.

- Chuang YC, Kaufmann JH, Chancellor DD (2014) Bladder instillation of liposome encapsulated onabotulinumtoxin A improves overactive bladder symptoms: a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial. J Urol 192(6): 1743-1749.

- Anderson RJ, Berl TB, McDonald KM (1976) Evidence for an in vivo antagonism between vasopressin and prostaglandin in the mammalian kidney. J Clin Invest 56(2): 420-426.

- Grantham JJ, Orloff J (1968) Effect of Prostaglandin E on the permeability response of the isolated collecting tubule to vasopressin, adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate, and theophylline. J Clin Invest 47(5): 1154-1161.

- Zusman R (1981) Prostaglandins, vasopressin, and renal water reabsorption. The Medical clinics of North America 65(4): 915-925.

- Switalska HI (1983) Circadian rhythm of PGE2, PGF2α and 6-keto-PGF1α urinary excretion in healthy women. ProstagLeukotr Med 11(2): 233-240.

- Kamperis K, Hansen M, Hagstroem S (2004) The Circadian Rhythm of Urine Production, and Urinary Vasopressin and Prostaglin E2 Excretion in Healthy Children. JUrol171(9Pt2): 2571-2575.

- Kim JC, Park EY, Hong SH (2005) Changes of urinary nerve growth factor and prostaglandins in male patients with overactive bladder symptom. Int J Urol 12(10): 875-880.

- Kim, JC, Park EY, Seo SI (2006) Nerve growth factor and prostaglandins in the urine of female patients with overactive bladder. J Urol 175(5): 1773-1776.

- Robert G, Salagierski M, Schalken JA (2010) Inflammation and benign prostatic hyperplasia: cause or consequence? Prog Urol 20(6): 402-407.

- Kwon YK, Choe MS, Seo KW, Park CH, Chang HS, et al. (2010) The effect of intraprostatic chronic inflammation on benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment.Korean J Urol 51(4): 266-270.

- Lee KC, Rauscher F, Kaminesky J, Ryndin I, Lei Xie, et al. (2019b) Novel immediate/sustained release formulation of acetaminophen-ibuprofen combination (Paxerol®) for severe nocturia associated with overactive bladder: A multi-center, randomized, double blinded, placebo-controlled, 4-arm trial. NeurourolUrodyn 38(2): 740-748.

- Anderson BJ (2008) Paracetamol (acetaminophen): Mechanisms of action. Pedi Anesth 18(10): 915-921.

- Chavez ML, DeKorte CJ (2008) Valdecoxib: A review. Clin Ther 25(3): 817-851.

- Merry AF, Gibbs RD, Edwards J, GS Ting, C Frampton, et al. (2010) Combined acetaminophen and ibuprofen for pain relief after oral surgery in adults; a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaest 104(1): 80-88.

- Ong CK, Seymour RA, Lirk P (2010) Combining Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) with Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs: A Qualitative Systematic Review of Analgesic Efficacy for Acute Postoperative Pain. AnesthAnalg 110(4): 1170-1179.

- (2018) National Institute for Health Research (NIHR):Fedovapagon for nocturia in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Evidence Briefing,p. 1.

- Vantia Therapeutics (2017) Vantia Therapeutics announces Positive Results from its Phase III EQUINOC® Study, a Pivotal Trial with Fedovapagon for the Treatment of Nocturia in Men with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia,p. 3.

- Abe Y, Nakano Y, Kanazawa T, Furihata T,Endo T, et al. (2016) Investigation of drug-drug interactions between ritobegron, a selective β3-adrenoceptor agonist, with probenecid in healthy men. CliPharmacol Drug Dev 5(3):201-207.

- (2009) Study No. NCT00742833: A Phase 2 study of ritobegron in patients with OAB.

- (2009) Study No. NCT01003405: Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of ritobegron in Patients with Overactive Bladder.

- (2019) Study No. NCT01004315: A Confirmatory Study of ritobegron in Patients with Overactive Bladder.

- Peyronnet B, Bruckner BM, Michel MC (2018) Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: What’s New in Medical Treatment? Euro Urol Focus 4(1): 17-24.

- (2019) Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency.

- Michel MC, Harding SE, Bond RA (2010) Are there functional β3-adrenoceptors in the human heart? Br J Pharmacol 162: 817.

- Mo W, Michel MC, Lee XW (2017) The β3 - adrenoceptor agonist mirabegron increases human atrial force through b1-adrenoceptors: an indirect mechanism? Br J Pharmacol 174(6): 2706-2715.

- Rackley R, Weiss JP, Rovner ES (2006b) Nighttime dosing with tolterodine reduces overactive bladder-related nocturnal micturitions in patients with overactive bladder and nocturia. Urology 67(4): 731-736.

- Le Fanu J (2001) The value of aspirin in controlling the symptoms of nocturnal polyuria. B J U Int 88(1): 126-127.

- Addla SK, Adeyoju AB, Neilson D (2006) Diclofenac for treatment of nocturia caused by nocturnal polyuria: a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Eur Urol 49(4): 720-726.

- Addla S, Adeyoju A, Neilson D (2014) NSAIDS for nocturnal polyuria - an observational study.

- AlWaili NS (2002) Increased urinary nitrite excretion in primary enuresis: effects of indomethacin treatment on urinary and serum osmolality and electrolytes, urinary volumes and nitrite excretion. BJU Int 90(3): 294-301.

- Presti JC (1995) Indomethacin and symptomatic relief of benign prostatic hyperplasia. JAMA 273(4): 347.

- Addla SK, Adeyoju AB, Neilson D (2006) Diclofenac for treatment of nocturia caused by nocturnal polyuria: a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Eur Urol 49(4): 720-725.

- Falahatkar S, Mokhtari G, Pourreza F (2008) Celecoxib for treatment of nocturia caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Urology 72(4): 813-816.

- Sengottayan V, Vasudeva P, Dalela D (2009) A novel approach to management of nocturia in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Indian J Urol 25(2): 280-281.

- Gorgel SN, Sefik E, Kose O (2003) The effect of combined therapy with tamsulosin hydrochloride and meloxicam in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia symptoms and impact on nocturia and sleep quality. Int. Braz J Urol 39(5): 657-662.

- Araki T, Yokoyamay T, Kumonz H (2004) Effectiveness of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug for nocturia on patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a prospective non-randomized study of loxoprofen sodium 60mg once daily before sleeping.Acta Medica Okayama 58(1): 45-49.

- Saito M, Kawatani M, Kinoshita Y (2005) Effectiveness of loxoprofen on patients with nocturia. Int J Urol 12(8): 779-782.

- Araki T, Yokoyamay T, Arakiz M, Furuya S (2008) A Clinical Investigation of the Mechanism of Loxoprofen, a Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug, for Patients with Nocturia. Acta Medica Okayama 62(6): 373-378.

- Shin HI, Kim BH, Change HS (2011) Long-Term Effect of Loxoprofen Sodium on Nocturia in Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia.Korean J Urol 52(4): 265-268.

- Sakalis VI, Karavitakis M, Bedretdinova D, Bach T, Bosch JLHR, et al. (2017) Medical Treatment of Nocturia in Men with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Systematic Review by the European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel for Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms.European Urology 72(5): 757-769.