The Impact of Training Chemistry Through the Medium of Mother Tongue (Afan Oromo) in Some Selected Teacher Education Colleges of Oromia Region, Ethiopia

Bulti Wayessa Muleta and Chali Abate Jote*

Department of Chemistry, Nekemte College of Teacher Education, Ethiopia

Submission: May 25, 2019;Published: July 02, 2019

*Corresponding author:Chali Abate Jote, Department of Chemistry, Stream of Natural Sciences, Nekemte College of Teacher Education, Post Box No. 88, Nekemte, Ethiopia

How to cite this article: Bulti W M, Chali A J. The Impact of Training Chemistry Through the Medium of Mother Tongue (Afan Oromo) in Some Selected Teacher Education Colleges of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Ann Rev Resear. 2019; 4(5): 555650. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2019.04.555650

Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to examine the impact of training chemistry through the medium of mother tongue, Afan Oromo. The study was conducted in two of the six teacher training colleges in Oromia regional state. Data collection instruments used was questionnaires, interviews, and focus group discussion. Data obtained from questionnaires were analyzed quantitatively using statistical tools like SPSS vertion-12 and percentage. The data obtained from interviews and focus discussion groups were analyzed by combining methods from content analysis qualitatively. The result of the study showed that, impact of training chemistry through the medium of mother tongue Afan Oromo was generally have positive impacts through facilitating easy communication and understandable of the lesson during training. But several factors like lack of resources, unavailability of translated textbooks and references books in mother tongue, poor experiences trainers, poor integration between content language etc. Thus, the colleges and concerned bodies should address these problems jointly. Hence the researchers forwarded finding and conclusions, recommendation were to alleviate the existing problems. Accordingly, supply resources, instructional materials, hiring experienced instructors, giving training on how teach mother tongue language and other which assumed to solve the identified problems were recommended.

Keywords: Impacts, Training, Mother tongue, Afan Oromo, Chemistry, Colleges, Oromia, Submersion, Diverse ethnic, Religious, learning institutions, Democratic culture, Dissemination, Socio-cultural issues, Linguistic questions, Exploratory analysis, Educational policy, Delimitation, Ghanian children's, Thinking tools, Pedagogical

Introduction

The role of mother tongue in education has long been debated [1]. The main theory that underlies the policy of education through mother tongue is the view that children need to master education appropriately in their native language before they can use a second language as their medium of instruction [1,2]. As language is a tool that is used for expressing information and ideas, it is important for students to develop their scientific knowledge and for teacher educators to understand the learning processes of students by developing the ability to communicate the subject matter in the classroom and to optimize their learning [2,3]. The implication of this view for chemistry teacher educators is that they need to develop critical and sensitive awareness of how language works in the classroom. This awareness needs to take account of the constant dynamic interaction between language and subject matter (chemistry) thought [4]. In addition, teacher educators ought to be aware of the impact of language in school achievement. Instruction through a language that student teachers do not speak has been called “submersion’’ [5]. Teaching learners in a language they do not know is analogous to holding students under water without first teaching them how to swim. Submersion makes both learning and teaching extremely difficult [3,5].

Ethiopia is a country of more than 70 million people characterized by diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious groups. Currently, the country is attempting to promote the UNESCO’s agenda of education through the mother tongue. From the point of view of linguistic human rights, one can say that the decision is an important step in language and social policy. As part of this, the country has made some changes in the education sector and in the school curriculum. One the change is the decentralization of education with the introduction of use of regional languages for instruction [6].

For example, the country’s 1994 Education and Training Policy draft outlines the close association between the recognition of political rights of linguistic groups and the educational implication of using local language as a medium of instruction in the primary education. Following the formulation of the policy, Amharic, Tigrinya, Afaan Oromo, Wellayta, Sidama, Kaffico, Benchi, Somali, Afar, Haddiya, Kembatta, and Gideo were immediately used to offer primary education [7].

The Oromo language became one of the regional languages, which achieved this status. Today, we have several Oromo dictionaries, works of art, academic works in and about the Oromo language. The tasks of developing and creating the vocabulary required to fulfill the Oromo students’ and researchers’ desire to communicate about modern academic, social, political and educational issues have since been carried out. Moreover, the language has become one of the fields of study in the education faculties of some higher learning institutions in the country. The language has also become the medium of instruction for primary schools and colleges in the Regional State of Oromia [8].

The Ethiopian Education and Training Policy document contains details regarding problems of relevance, quality, accessibility, equity, mode of delivery and education that have impede training in the past. In response to these challenges, the document recommends changes in the school curriculum, language of instruction and student teacher training programs. The document asserts that these change are necessary for making education more responsive to educational and development which included, among other things, a greater emphasis upon problem- solving at all levels, an increasing the number of teachers needed for the huge growth in demand, wiser use of resources, an increase in democratic culture, more efficient dissemination of science and technology and creation of an education system more responsive to society’s needs. The document also attempts to emphasize the importance of integrating teacher education with socio-cultural issues such as linguistic questions [1,5].

The language policy of the Transitional Government of Ethiopia (1994) stated that, nations and nationalities in the country can either use their own language or can choose to use others based on national and countrywide distribution. One of the outcomes of the new language and education policy in Ethiopia is the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of training in the Regional State of Oromia. Today, all the Teacher Education Colleges in the Regional State of Oromia are offering their training in Afan Oromo [6,9].

Statement of the problem

The current study is about the impact of training chemistry through the medium of mother tongue (Afaan Oromo) in selected colleges of teacher education found in the Regional State of Oromia. The study is therefore an exploratory analysis of the students and teacher trainer’s perceptions of the relative values of the use of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, in the training program and their observations of the factors that negatively affect the proper integration of language and content. One of the changes in educational practice in the Regional State of Oromia is the use of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, as a medium of instruction for primary education and its subsequent development as the language for training future primary teachers studying in the six colleges in the regional state. The idea behind training teachers in Afaan Oromo is to prepare them for their future challenge as primary teachers where the language is used as a medium of instruction.

The language has now been in use as a medium of training since September 2003 in the Teacher Education Colleges. A considerable number of students have already graduated and are working in the primary schools in different zones of the regional state. The colleges are continuing to produce many teachers using Afaan Oromo as a medium of instruction. Included in the number of teachers across different subjects, they are producing chemistry teachers to fill the human resource requirement for primary education. However, the main issue currently is that, although the policy has been implemented and has already resulted in the production of a large number of teachers, no study has so far been conducted to examine the impact of the use of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo as a medium of training, the problems encountered during the implementation process and what the students and their trainers feel about the status of the overall training program. This means there is an important research gap to be filled. The purpose of the current study is, therefore, to investigate the overall situation regarding the use of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo to train chemistry teachers and the training process in general as well as to examin6 actors that affect the proper implications of the training in with specific emphasis on the chemistry teacher training in selected colleges in the region.

Accordingly, the study is designed to respond to the following basic questions.

a) What is the opinion of teacher trainers and students towards using mother tongue, Afan Oromo, as a medium training?

b) What are the factors that affect the proper use of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, as a medium of training?

c) What is the overall situation regarding materials and training status in the selected colleges?

Objectives of the study

The main objectives of the study are:

a) To identify the opinion of students and teacher trainer’s perception towards using mother tongue as medium of training

b) To investigate factors that hinders the implementation of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, as the medium of training in chemistry education.

c) To find out the overall situation in regarding to materials and training status in selected Oromia colleges.

Significance of the study

The importance of the study was stated as follows.

a) It may provide the sample teacher education colleges of the Regional State of Oromia with significant information about the status of the use of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, as the medium of instruction to train chemistry teachers.

b) It may provide the policy makers with some insights regarding the factors that impact on the effective implementation of both linguistic and educational policy.

c) The study may also provide the Education Bureau of the Regional State of Oromia with an informative link between education, language, teacher quality and the training process.

d) It may create awareness among chemistry teacher trainers regarding possible means of achieving effective communication of science and science education through mother tongue.

e) Finally, the study may shed some light on the type of training and professional development students may need to undergo about the implementation of the language policy.

Delimitation of the study

This study was confined to the experiences of two colleges in the Regional State of Oromia. The two colleges were Asella College of Teacher Education and Nekemte College of Teacher Education. The data required for the study was collected from a group of teacher trainers and students in the chemistry departments of these two colleges. The fact that the study was limited to two of the existing six colleges means that it does not claim both thoroughness and breadth about the hopes and challenges in using mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, as the medium of instruction. Finally, the data was generated only from a limited number of students and teacher trainers. As a result, the study may not incorporate the feeling and perception of all.

Literature Review

Language is a key factor whether we learn Chemistry, Biology, and Physics, Science or Mathematics [10]. According to Stepanek Learning is a process of developing and negotiating meaning, which is usually achieved through the medium of language to convey ideas whether from teacher to student, from student to teacher, or among students as they build meaning together all must be able to use language. There are controversies on the advantage of mother tongue for learners. One study showed that the use of the mother tongue facilitated learning and expression of concepts among Swazi students while a study among Melanesian students showed little transference in knowledge between the school and the village. The later study suggested that science could be being at odds with students’ daily world [10]. As Waldrip state that, learning science is like learning a foreign language. Therefore, to be fluent in science requires practice in speaking the language. An understanding of a concept has been demonstrated when a person can confidently deliver a message to an audience. It is when we must put words together and make sense, when we must formulate questions, argue, reason, and generalize, that we learn the thematic of science [11]. Stepanek also holds the idea that as language is the primary means of teaching, students’ ability to participate in science depend to a large extent on their ability to listen, speak, read and write in the medium of their instructions. According to him, sciences require the ability to understand specialized vocabulary and specialized meanings of ordinary words. The other thing, which science students need, is the ability to express their thoughts and to communicate their understandings. His view is that language proficiency plays significant roles in the mastery educational concepts and in stimulating learners to communicate with their teachers and among themselves [10,12].

The role of the mother tongue in the acquisition of knowledge has been promoted over the last several decades. Stepanek makes the following comments regarding the relative advantages and disadvantages of English and native languages; native languages are resources for learning because students are more successful when they continue to develop their native language skills rather than focusing exclusively on learning in English. Teachers use familiar language to teach an unknown concept or use unfamiliar language when dealing with a known concept. For example, a teacher may encourage the students to draw on their native languages as they begin developing their understanding of a new concept, before she/he introduces them to English vocabulary [10,12,13]. Various other studies conducted in Africa and other developing world also support the above view. Before three decades, the study made on Ghanian children’s “scientific understanding as they participated in an inquiry-based constructivist curriculum found that the children’s conceptual understanding reached much higher levels of complexity in the first language than it did in the second language” [14]. More recent studies similarly indicated that a better cognitive development is achieved faster when learners study in their mother tongues than when they strive to learn in the language that they have little control on [15].

Study carried out with learners on the use of the mother tongue in scientific discourse had resulted in the positive outcomes of; greater participation, increased ability to express themselves in a variety of tasks, greater motivation and optimism, broader range of thinking tools, and better connectivity with concepts in own life-world culture [16]. From this point of view, training chemistry students through the medium of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, has advantage both for society as well as for the students themselves. However, the policy will not be effective without a system that makes it work. The experiences in Africa and other part of the world showed that there is no problem with the idea of using the mother tongue for education. It is justifiable from political, pedagogical and socio-cultural angles. Both the failures and success stories about the policy of education through the mother tongue are strongly linked to the complex socio-political, administrative, attitudinal and economic factors [7,12,13].

Bearing in mind how language influences the chemistry education (thought) process of the students, an understanding of self and the learning of chemistry, deliberate efforts should be made to enable students to learn chemistry in mother tongue, Afaan Oromo as much as possible. The idea of forcing students to think in the foreign language is unproductive [17]. It does not help students to be creative but reduces them to a “robot” that merely takes notes given to them by their teacher educators and reproduces some when required without demonstrating an understanding of the scientific and technological information and process under consideration. About teacher education, the most important issue is being able to create students who are literate in chemistry science and conceptually powerful and producing future teachers capable of teaching chemistry as effectively and efficiently as possible. So, the aim of science education is to provide pupils with experiences that help them become more scientifically literate and a scientifically literate person is one who has; satisfactory experience with science process skills, positive attitude towards science, and wealth of scientific knowledge [18]. On his part, Buxton states that a scientifically literate individual is one who “understands key concepts and principals of science; is familiar with the natural world and recognizes both its diversity and unity; and uses scientific ways of thinking for individual and social purposes.” This is equally important for the education of chemistry teachers through mother tongue. However, there are ample factors that can exert both negative and positive impact on the use of mother tongue for the education of teachers and their learners [19].

One should know that it is in language that people’s histories, lived experiences, perspectives, dispositions, and innermost thoughts are realized and given expression [20]. Realizing this, proponents of bilingual education and multiculturalism have long been in favor of education through the mother tongue. Such advocacy is based on the premises that when they study subject matter children learn things easily and become confident about their language. Moreover, the role of language in learning chemistry (science) is being focused on by chemistry (science) education researchers from a few perspectives. With a constructivist paradigm dominating the field, attempts have been made to assess the role of language in facilitating and assessing learning and in understanding complex interactions related to chemistry (science) teaching and learning [20]. In similar way, the role that language plays in the chemistry classroom is not simple, and there are numerous ways in which the interaction between language and learning is important to the classroom teacher educator. Linguistic demands of assessment for example, put some student teachers at a disadvantage [21]. There is also a need to allow learners to find a variety of ways to express their thoughts [22].

In addition to exploring how language facilitates learning, it is important to understand ways in which language may become a barrier to understanding. Osborne and Freyberg discuss problems created by the different meanings that children and adults may have for specific words. Talking into consideration the experience of chemistry education Flick states that, in classrooms where chemistry is effectively taught, important learning is often forged from verbal negotiations as well as from evidence and experience. The teacher has traditionally been the focus of research by focusing on the language of questioning and student responses. However, interest in the role of language in teaching has grown beyond teacher-directed discourse to include student discourse in small groups as well as teacher-student interactions in a wide variety of contexts [15,23,24]. This problem may occur also at higher levels of educational experiences such as in teacher training colleges. Supporting this view, Marew, made the following points; in the training of students, the language of learning used during the training period plays a crucial role. It is through this language of learning that teacher trainees assimilate knowledge, concepts, principles and skills, from their content subjects, which are essential to the successful completion of their training programs and to their effectiveness as teachers thereafter [2,25].

Methods

Study design

The main purpose of the study was to assess the impact of training chemistry through medium of mother tongue in some selected teacher education colleges of Oromia. The descriptive approach was preferred since it allows an investigation of the concerned studies with specific predictions, narration of facts and characteristics of the situation as it exists at present. The specific reason why it was preferred in this study was that it shows the situation how mother tongue was being used as a medium of instruction and reveals the attitudes and perceptions of the target samples of the population.

Subjects of the study

The samples of the population of this study were students and teacher trainers in Nekemte Teacher College of Education (NCTE) and Assela Teacher College of Education (ACTE). In these colleges there were a total population of 560 chemistry students, and 7 chemistry instructors.

Sampling techniques

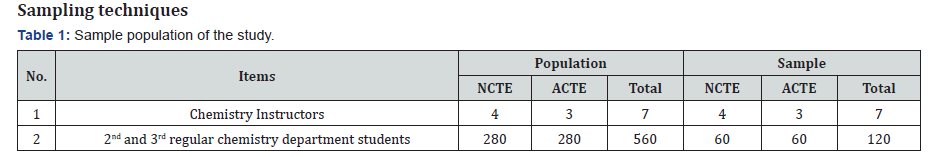

The sample population of the study was obtained from Nekemte College of Teacher Education (NCTE) and Asella College of Teacher education (ACTE). Chemistry instructors and 2nd and 3rd year regular chemistry department students were included in the study. This is shown here under the following in Table 1.

Concerning the sampling techniques 2nd and 3rd year regular chemistry department students was selected using simple random sampling. Because in simple random sampling every individual in the populations have the same chance of being selected for the sample. As to Kothari [26] simple random sampling provides each items of the population equal chance of inclusion in the sample. Availability sampling would be employed to select Chemistry instructors. Because, they are few in number and by virtue of the rich information they have about the study topic and Purposive sampling was employed to select the two colleges that could be representative on the basis of their locations as they are found in the western and eastern part of the Oromia region where the study could be more significant in terms of the overall gains the achievements in chemistry.

Data collection instrument

In order achieve the objectives, the instruments used to collect data for the study was questionnaires, interview and focus group discussion.

a) Questionnaires

The original self-designed questionnaires were prepared and issued to students and contained both closed and open ended questions on students’ attitudes towards the use of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, as a medium of instruction, students’ perceptions about the impact of the various problems they observed (trainer-related problems and resource-related problems) and the extent to which the suggested solutions could be useful with regard to improving the situation of training in mother tongue, Afaan Oromo. The questionnaires were administered after the total sample was selected by the researcher to whom the objective of the study was briefed. This was followed by distribution of the questionnaires to the students asking them to take enough time and return the completed materials after some time.

b) Interviews

The second type of instrument used to generate data was interviewing. The researcher designed five structured open questions that were centered around the implementation of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo as a medium of instruction in training, the challenges faced during the implementation and how to overcome the challenges during the implementation.

c) Focus-group discussion

Focus-group discussion was conducted with students from the selected sample by employing random systematic techniques and selects a total of 12 students from NCTE and following the same procedure for ACTE. The researcher also included two interested teacher trainer one from each college for the discussion. The discussion was taking place separately by selected participants at their colleges. The objectives followed similar lines as the other methods selected, namely, to explore the attitudes, perceptions and challenges facing the successful implementation of mother tongue, Afaan Oromo, as a medium of instruction. The discussion was recorded by using audio and video techniques.

Procedure of data collection

The pilot test, made of questionnaire items and administered to 12 purposely selected students, evidently showed that because of possible misunderstanding (confusion) with the meanings of some terms of the English language used in designing the questionnaire, it was found practically difficult to obtain the desired responses from the target sample. In this fact, the researcher could not be able to maintain the initial plan of conducting the whole opinion survey in English language for this sample group. Hence the researcher could not have other option than considering the translation of all the questionnaires items, which were previously designed in English language into the vernacular mother tongue, or Afaan Oromo language so that to achieve effectively his intended goals. To this effect, the task of translation was taken up very seriously by the researcher through the assistance and advice of some teacher educators working in the language department of the NCTE. The Afaan Oromo version of the questionnaire items were thoroughly proofread and tested for validity by a language specialist in the department who is known for his qualification and rich experience of research in linguistic studies. In addition, interviews and focus group discussion were carried out by the researcher himself.

Methods of Data Analysis

The data obtained from closed ended questionnaires was tabulated and described quantitatively. The analysis was made by employing the descriptive statistic through percentage technique and the result was processed by SPSS version-12. The data obtained from open ended questionnaires, interviews and focus group discussion were analyzed quantitatively as content analysis.

Result and Discussion

Analysis of quantitative data

For this part of the study, the students were the main participants in which to investigate the attitudes and constraints in chemistry training during the implementation of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction.

Attitudes of students towards the use of Afan Oromo language as a medium of instruction

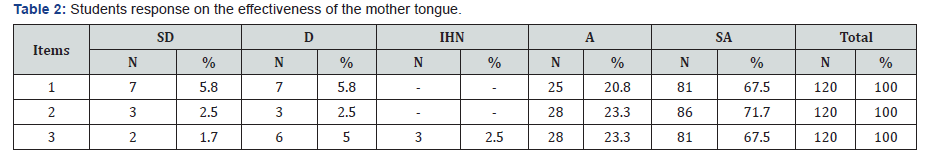

a. The effectiveness of the mother tongue in chemistry instruction

Table 2 illustrates that most of the respondents (88.3%) pointed out that they learn chemistry most effectively through Afan Oromo. It also shows that about 95.0% of the respondents agreed that the mother tongue is the best medium of instruction. An equally significant number of them (90.8%) indicated that they benefit greatly from being trained in their mother tongue. When we look at the combined percentages here, we see that the trainees pointing out the positive effects they see from using Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction in the classroom instructions.

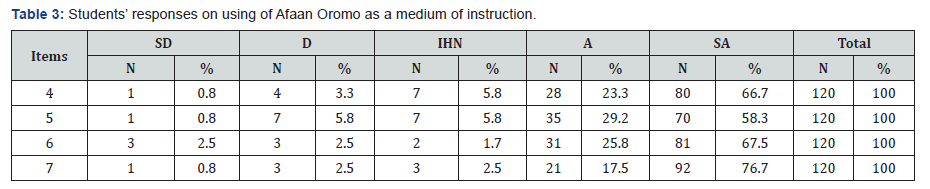

b. Using the Afan Oromo language as a medium of instruction in the chemistry lesson

Table 3 Shows that most of the respondents (90.0%) believe that use of the Oromo language as a medium of instruction enhances trainees’ self-learning ability and confidence. It also indicates that a great majority (87.5%) of the respondents indicated that Oromo language as a medium of instruction improves relationships between trainees and trainers. As the data demonstrate, most of the respondents (93.3%) are of the opinion that the Oromo language as a medium of instruction increases students’ participation. Still most of the respondents (94.2%) also pointed out that Afan Oromo language as a medium of instruction provides more opportunities for trainees to discuss other academic issues related to chemistry freely and confidently. This suggests that overall the use of Afan Oromo, as a medium of instruction in the chemistry classroom is rated as very important. Therefore, according to these results, one can conclude that the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction in the chemistry classroom has greatly helped in self-learning capabilities as well as their ability to discuss academic issues freely. So, the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction appears to be well-accepted by the students in the sample Colleges of Teacher Education who were subject of the study.

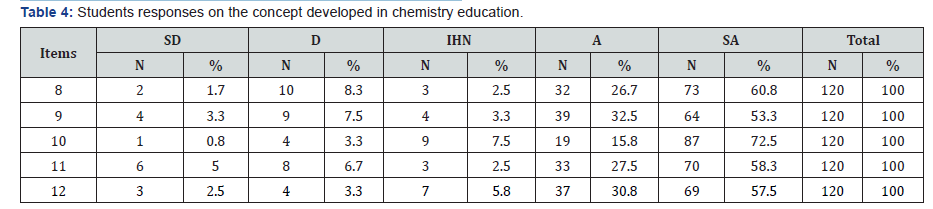

c. Students’ attitudes towards the concept of chemistry education developed during the training

The Table 4 above indicates that 87.5% of the respondents agreed that using Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction encourages communication. In addition, it also reveals that a significant number of the respondents 85.8% agreed that the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction in chemistry classroom has enhanced their academic, linguistic and cognitive achievements.

From Table 4 again, one can see that about 88.3% of the respondents suggested that the effective learning of the contents is not mastered if it is not carefully planned and monitored. Furthermore, 85.8% the respondents state the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction has helped the trainees to develop self-concept, self-confidence, and academic competence. 88. 3% of the respondents did agree that the use of Afan Oromo in preparing future teachers could possible stimulates the trainees’ thinking skills. To sum up, the responses obtained from students have revealed the high level of importance attached to Afaan Oromo as a medium of instruction.

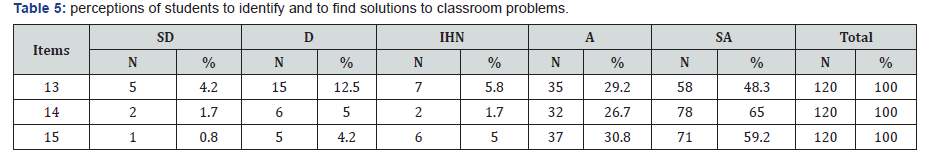

d. The autonomy of trainees to identify and to find solutions to classroom problems

From the data in Table 5, one can see that about 77.5% of the respondents revealed the fact that Afan Oromo facilitates the training of subject content in chemistry. In addition, 91.7% of the respondents indicated that training in the Afan Oromo language may allow students to freely reflect on different issues to build a greater understanding of what they have been learning in chemistry class. Thus, 90.0% of the respondents believed that using Afan Oromo in training classroom promotes the autonomy of the trainees to identify and to be effective in their classroom interaction. Therefore, from the research subjects’ responses given above, it is possible to conclude that the student teachers gave their consent that chemistry training in Afan Oromo can serve as a necessary means of grasping the concepts of the subject matter easily. This adds to the strong conviction (position) already held by the researcher that Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction in the classroom has many advantages for chemistry training in Oromia Colleges of Teacher Education.

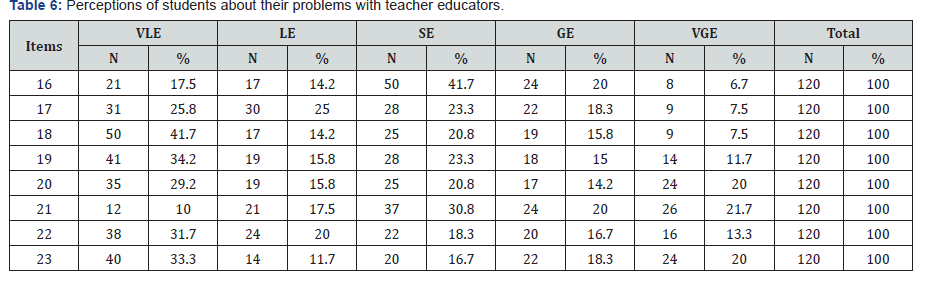

e. Students’ perception about the impact of the various problems they have observed

Table 6 above indicates perception of student s about the fact that there are problems associated with trainers on the implementation of Afan Oromo as a medium Chemistry Instruction. To mention a few, a lack of confidence among some teacher-trainers (41.7%), observable disaffection and alienation (50.8%), stress experienced by trainers while using Afan Oromo as medium of instruction (55.9%), insufficient preparation and knowledge of the language (50.0.3%), low numbers of trained and experienced teachers who are fluent speakers of the language of instruction (45.0%), due to the fact that they trained before in English (41.7%), lack of discussion among themselves how to overcome the problems related to the use of Afan Oromo in chemistry Education (51.7%), and low levels of involvement of trainees in the construction of chemistry concepts (42.0%).

The data presented in Table 5 makes clear the constraints experienced by the teacher trainers that are in average 47.16%, 23.56% and 29.29% little, some and great extents respectively. This show that the constraints experienced by the teacher trainers that to a little extent. Therefore, the majority of respondents in the sample (except the teacher trainers who trained before in English) still showed mildly favorable attitudes towards the teaching by teacher trainers being conducted in Afan Oromo, which leads to the assumption that the problems or constraints do not appear to affect the on-going teaching and learning. It can therefore also be assumed that this would be not only be the case in the colleges of Oromia Teacher Education but rather in any situation where the mother tongue is used as a medium of instruction.

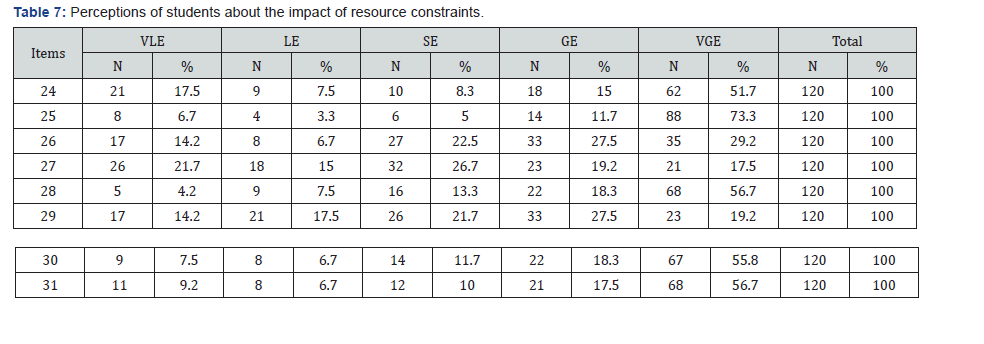

f. Students’ attitude towards the impact of resource related constraints on the implementation of the training program

From Table 7, it can be seen that 66.7 % of the respondents pointed out that scarcity of quality materials greatly affects the effective implementation of the training program. 85.0% of the respondents agreed that the colleges do not have enough reference materials to help the student teachers training in chemistry in an appropriate manner. It can be seen from the data that 56.7% of the respondents indicated that a lack of formal manuals for laboratory activities in Afan Oromo impeded the trainees’ ability to relate the concept of chemistry to surrounding society and to apply scientific technology. On the other hand, 63.4% of the respondents suggested that there is poor integration between the content and Afan Oromo that used to express concepts in chemistry education. In addition, 75.0% of the respondents reveal that the colleges have problems regarding the sufficiency, range, and appropriateness of handouts which are used for the training of the trainees in chemistry classroom. 46.7% of the respondents suggest that the available written materials were not displayed in ways appropriate for trainees’ access. Likewise, 74.1% of the respondents highlighted the problem of the provision of supplementary chemistry learning materials that would offer students greater choice and flexibility during training program. In addition, one can see from the result that 74.2% of the respondents were in agreement that there were no written materials in Afan Oromo relating to chemistry education in colleges that could help to address the various learning objectives and goals set by the Ministry of Education for this level of training of students. Due to this material such as lack of resources, non-availability of translated textbooks and supplementary materials as well as financial constraints for such additional expenses required for teacher training and materials production hinder the implementation of training through mother tongue. So, depending on the result most of the respondents in average more than 90% revealed the constraints. Therefore, from the overall issues addressed here in this investigation, one can infer that the resource- related constraints are the main factors that impede the implementation of Afan Oromo language as a medium of instruction for training students in chemistry education at the sample of Teacher Education found in the Oromia Regional State.

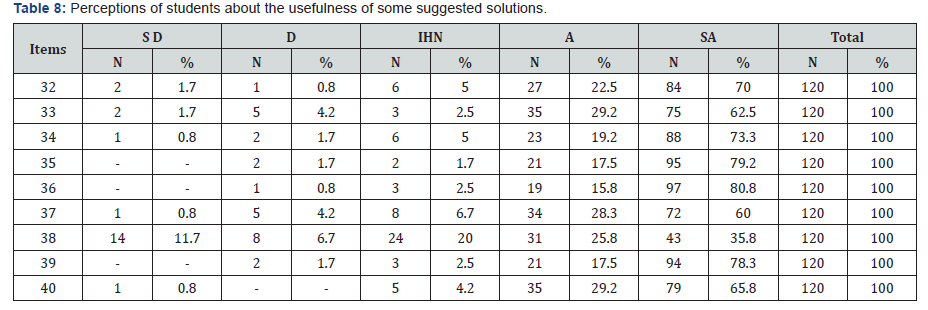

g. Perceptions of students about some suggested solutions aiming at improving the conditions of training chemistry in afan oromo language

In this section, the findings about the perceptions of students about the extent with which the suggested solutions could be useful for improving the conditions of training in chemistry education using Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction in the Colleges of Teacher Education.

Table 8 above illustrates the fact that 92.5% of the respondents have stressed the importance of training for teacher trainers, not only in the subject content but also in use Afan Oromo, to teach effectively. As indicated from the data, 91.7% of the respondents highlighted the importance of training chemistry teacher trainers’ language skills as well so as to enable them employ their Afan Oromo effectively and efficiently as a medium of instruction and in effect for improving their skills in pedagogy as that could help mastery of it as a language of instruction. In addition to this, most of the respondents (92.5%) agree that teacher trainers and students need enough materials on how to use Afan Oromo to train successfully. 96.7% of the respondents would like to see the standardization of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction.

As one can see, almost all the respondents (96.6%) pointed out that conducting periodic evaluation, revision, and improvement of written materials in Afan Oromo by concerned bodies is crucial. In addition, 88.3% of the respondents have reflected about the necessity of involving student teachers in the translation and the definition of technical concepts of chemistry so that to foster a high level of reflection amongst students. The study also showed that 61.6% of the respondents did agree with the fact that success in training depends upon the trainees’ mastery of academic language. As can be seen from the result in Table 8, most of the respondents (95.8%) believed teacher educators required a good knowledge of Afan Oromo and the skills for using it as a medium of instruction in order to be effective trainers at the colleges. Almost all the respondents, (94.6%) believed that the trainers themselves could benefit by involving their trainees in the redefining and translating of certain chemical concepts in Afan Oromo. From the overall picture here, one can argue with the review that chemistry training given in Afan Oromo requires the development of a large bank of appropriate scientific words, terms, and phrases in this language. In addition, chemistry teacher trainers should be well-versed in the Afan Oromo language and be able to use it properly to communicate with the students. It suggests that if these requirements were met, the development of the subject of chemistry taught in Oromia Colleges could take place effectively.

Analysis of qualitative data

Teacher trainers’ and their students’ attitudes and experiences regarding the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of training in chemistry education: When they were asked to explain about their attitudes and experiences regarding the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of training in chemistry education, most of the respondents (students and teacher trainers) had good perceptions and positive experiences. As observed before in quantitative analysis, students argued that they had very good perceptions regarding Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction in the chemistry training education.

For example, six of the teacher trainers replied that, even though they face some problems such as a lack of text books and reference materials, chemistry training using Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction has various important advantages in that it increases the interaction of students on chemistry content, creates interest in both students and teacher trainers, stimulates free discussion on concepts of chemistry, facilitates the achievement of the objectives of Teacher Education and minimizes the difficulty of using the foreign language which represents a further barrier in achievement.

In similar way, almost all the respondents who participated in focus group discussion said that training in Afan Oromo caused no problem. As the students indicated, using Afan Oromo during training sessions is very motivating and conducive for free and easy communication between trainers and trainees as well as among the trainees, so that in consequence the understanding of the concepts in the subject area becomes relatively sound and the trainees feel more self-confident. They felt confident when using Afan Oromo in training sessions. This was also highlighted by the teacher trainers who participated in the discussion. Students viewed that in the previous curriculum, when the lesson was given in English, they were afraid to ask questions in the class. They also felt that teachers could not understand questions posed by their students, as it was difficult for the students to express themselves in English. The students, therefore, did not ask questions and left the class without understanding the concepts. However, when learning in Afan Oromo now, students’ participation in asking and answering questions as well as in group discussions has greatly increased and teachers now a days experience no problems in communicating with their students. The situation generally allows more interaction on subject content to take place easily than it used to be earlier when English Language was the medium of instruction.

However, one-teacher trainers criticized the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction due to the lack of resource materials for students written in Afan Oromo. Students are currently solely dependent on the use of one module and do not have the chance to develop independent learning skills. Therefore, given that language is needed to allow students and teacher trainers to find a variety of ways to express their thoughts, and many researchers confirm that using Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction guarantees the academic language proficiency of students and teacher trainers and facilitates the process of training and the understanding of the subject matter.

Challenges facing the students and teacher trainers: In their response to the question “How have you been meeting the challenges of training through Afan Oromo?”, many of the respondents replied that there was a lack of resources for student teachers and teacher trainers. As Table 6 of the quantitative analysis shows, the constraints can have implications for the effective implementation of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction. Most of the teacher trainers in their interviews argued that they are confronted by a major challenge when students go to the library out with class to access reference materials all of which are available only in English, which creates confusion amongst the students. In addition, most of students indicated in open-ended questions that in the available reference books in colleges that are written or translated in Afan Oromo, some terms, and words of the language are not standardized. The meaning of some terms that are taken from the English and the meaning in Afan Oromo sometimes do not match because experts did not prepare the modules. Finally, the participants of focus group discussion expressed an interest in teaching and learning chemistry in Afan Oromo but also voiced their concerns about being able to upgrade their educational status on a degree program in this language due to the current lack of continuity.

When students and teacher educators were asked on how they have been meeting the challenges of training through Afan Oromo, they have praised the training but, at the same time, have acknowledged the challenges such as lack of translated textbooks, modules and reference books for both the students and teacher trainers and mentioned the fact that, even in the translated modules, some scientific words do not have exact equivalents and some terms used to translate the modules were not standard.

The written and oral responses revealed that almost all the respondents believed that they had serious resource constraints facing them. The study argues that, from the above analysis, these are the main challenges, which exist in the Oromia Colleges of Teacher Education and hinder the effective implementation of Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction.

Teacher trainers’ and students’ views regarding the means to overcoming the challenges: The study looked at ways of overcoming the challenges faced based on suggestions made by students and teacher trainers. The students and teacher trainers were asked in open ended questions, interviews and focus group discussions: “how do you think the challenges could be met regarding the lack of resource materials, skilled man power, curriculum-related constraints and other issues that you feel need improvement relating to chemistry training using Afan Oromo as a medium of instruction?”

Most of the respondents believe that the Oromia Regional Education Bureau has a fundamental role to play regarding the preparation of reference books and textbooks, the provision of a budget for the colleges, the inviting of professional people to translate into Afan Oromo, training, organizing seminar, evaluating, revising the written materials in Afan Oromo and appraising the standard of teacher trainers. In addition, it was felt that the student teachers must practice reading, questioning, answering, and explaining their views in class in Afan Oromo. The current courses are general courses and it would improve the situation if specific ones such as organic, inorganic, analytical and physical chemistry were offered as they would teach more concepts and improve the content and quality of the curriculum as well as the capacity of teacher trainers.

Finally, from the analysis of the qualitative data one can conclude that the overriding concerns pointed both by teacher trainers and their students is that it is not enough to elevate a language to develop to serve as a medium of training at college level. The quality of the materials, the evaluation schemes and quality-enhancement measures should be seriously considered. This calls for commitment on the parts of teacher trainers to ensure that materials are written and on standard-setters in initiating and implementing a plan of action.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The current study made clear that both teacher trainers and students of the selected colleges have positive regards towards the use of the Oromo language as a medium of training and pointed out their belief that using the language as the medium of training facilitated easy communication among them. The study suggested again that if properly implemented Afan Oromo can serve to communicate scientific concepts like any other language. The respondents’ reactions revealed however that the use of Afan Oromo as a medium of training takes base only when trainees find that they are engaged in a meaningful content and language learning process. In other words, the study suggested that communication with trainees is essential for effective training of students to take place. In order to communicate successfully, both the trainees and trainers must know the language well in order that a conducive and interesting training atmosphere can be created which increases the opportunities for the trainees to express the subject matter clearly in their work, enables them to be creative, to think logically, to examine things critically and to disseminate the intended concepts accurately.

Despite this however, the teacher trainers and student teachers pointed out a number of factors that impede an effective implementation of the Oromo language as a medium of training in the chemistry training education. Lack of resources, poor experiences of trainers, poor integration between content and language and lack of coordinating efforts are major factors that prevent an effective implementation of the policy. The undesirable outcome of these problems is that they would prevent the policy of language of instruction from becoming effectively implemented. In addition, these problems would prevent the proper delivery of content and skills for the trainees. The teacher trainers as well as their students suggested that the colleges, the educational bureau and other stakeholders should work together to overcome the problems. One of the main suggestions they made is that trainees and their trainers should learn from one another particularly regarding how to overcome conceptual gaps that are created during translation of scientific concepts into Afan Oromo.

Based on the conclusions made above, the study forwards the following recommendations:

a) The attitudes and perceptions of students and teacher trainers, which are outlined in the findings, highlight the fact that using Afan Oromo for teaching purposes in colleges is very important. Therefore, it would represent a positive step if it were to continue to be used as a medium of instruction at the present time as well as in the future.

b) The materials needed to train the student teachers at the Oromia Colleges of Teacher Education were not organized for such a purpose. Therefore, an important measure for the Ministry of Education or Regional Education Bureau of Oromia to take would be to set up a professional team to evaluate, revise and improve the standard of the written materials in Afan Oromo as well as to organize skilled staff for training purposes.

c) It could therefore also be advantageous for student teachers in Oromia Regional State to be able and continue their chemistry education at university level in their native language, Afan Oromo.

d) Evaluating and revising the curriculum is an integral part of the current education system. As students and teacher trainers indicated in their responses, it is hoped that such a process will take place regarding the standard of the chemistry curriculum used to train future teacher educators in Oromia Colleges of Teacher Education.

e) One of the chemistry teacher trainers need to do together is to develop conceptual vocabulary sufficiently to help students transmit scientific concepts. This stems from the fact that vocabulary is the starting point of the process of constructing meaning, developing conceptual understanding and communicating information about science.

f) The other thing that chemistry students and teacher educators should avoid is communicating in unfamiliar and vague language.

g) Finally, teacher educators should promote collaborative learning and problem-solving skills to overcome challenges, which the use of Afan Oromo poses as an educational challenge.

References

- Mullen J (2004) The Use of Mother Tongue as Medium of Instruction. Addis Ababa, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

- Fafunwa Foundation (2006) Implication of Teaching Science and Technology in the Mother Tongue.

- Nadine Dutcher (2003) Promise and Perils of Mother Tongue Education, Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC, USA.

- Wilson E, Spink A (2005) Making meaning in chemistry lessons. Electronic Journal of Literacy through Science, 4(2).

- Carol Benson (2004) The Importance of Mother Tongue Based Schooling for Education Quality: Center for Research on Bilingualism: Stockholm, Sweden.

- MOE 1994, 2003. Education Sector Development: Action Plan, Addis Ababa: Central Printing Press.

- Tekeste Negash (1996) The Ethiopian Education and Training Policy (EETP), 1994. Thinking Education in Ethiopia: Sweden, Nordiskaafricka Institute, Uppsala.

- Berhanu Bogale, Carol Benson, Heugh, K. And Mekonnen Alemu Gebre Yohannes, 2006. Final Report Study on Medium of Instruction in Primary Schools in Ethiopia Commissioned by the Ministry of Education.

- Thomas Bloor, Wondwosen Tamrat (1996) Issues in Ethiopia Policy and Education. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 17(5) Language studies unit, University, Birmingham B4 7ET, UK.

- Stepanek (2004) From Barriers to Bridges: Diverse Languages in Mathematics and Science.

- Waldrip BG (2002) Science words and explanations’: what do student teachers think they mean? Electronic Journal of Literacy Through Science 1(2).

- Djite PG (1993) Language and Development in Africa. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 100(101):149-166.

- Hameso S (1997) The language of education in Africa: the key issues. Language Culture and Curriculum 10(1): 1-13.

- Merino BJ (2001) How do teachers facilitate writing for bilingual learners in "sheltered constructivist" science? Electronic Journal of literacy through science 1(1).

- Yan DY, Ywong WT, Pui SC (2003) Evaluation of the effects of medium of instruction on the science learning of Hong Kong secondary students: Performance on the science achievement test. Bilingual Research Journal.

- Manzini ST (2000) The influence of a culturally relevant physical science curriculum on the learning experiences of African children. Unpublished M. Ed Thesis, University of Durban-Westville, Durban, South Africa.

- Dikshit O (1974) Student should be Encouraged to Think in a Foreign Language, Journal of the Nigerian Studies Association, 6(2): 47-52.

- Gibbons BA (2004) Supporting science education for English learners: promoting effective instructional techniques. Electronic Journal of literacy through science 7(3).

- Buxton CA (2001) Exploring science-literacy-in-practice: Implications for scientific literacy from an anthropological perspective. Electronic Journal of literacy through science 1(1).

- Walsh C (1991) Pedagogy and the Struggle for Voice: Issues of Language, Power, and Schooling for Puerto Ricans. New York: Bergin and Garvey, USA.

- Rudner LM (1993) Issues and concerns: Educational Resources, Improvement and Statistics (OREI & NCES)/Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC)/ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation/Essays, Bibliographies, & Resources/Alternative Assessment/Issues and Concerns.

- Hein GE, Price S (1994) Active assessment for active science: a guide for elementary school teachers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, UK.

- Osborne R, Freyberg P (1985) Learning in science: The implications of children's science. Auckland: Heinemann Education.

- Flick LB (1995) Language and Classroom Learning (introduction). In Kamen M, Bernhardt E (Eds.), A selected bibliography on language in science learning. Columbus, OH: The National Center for Science Teaching and Learning, USA.

- Marew Zewdie (2000) The Language of Learning in Teacher Education and Secondary School Practices Apractianers Enquiry. In: Mare Zewdie, et al. (Eds.) Secondary Teacher Education in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, British Council in Association with AAU and EANU.

- Kothari CR (2004) Quantitative Techniques (3rd edn). New Delhi: Vikas publishing House Pvt Ltd, India.