Combination of Psychotherapeutic Techniques to Adequately Cope Well with the Body Image Issues in Adolescents, Diagnosed with E-Wings Sarcoma Followed by Amputation - Two Case Series

Guru Prasanna Lakshmi*

Department of Clinical Psychology, Sweekaar Academy of Rehabilitation Sciences, Ind

Submission: January 08, 2018; Published: February 26, 2018

*Corresponding author: Guru Prasanna Lakshmi, Department of Clinical Psychology, Sweekaar Academy of Rehabilitation Sciences, India, Email: guru.psychologist@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Guru Prasanna Lakshmi. Combination of Psychotherapeutic Techniques to Adequately Cope Well with the Body Image Issues in Adolescents, Diagnosed with E-Wings Sarcoma Followed by Amputation - Two Case Series. Ann Rev Resear. 2018; 1(4): 555567. DOI: 10.19080/ARR.2018.01.555567

Abstract

Adolescence was seen as a time of great uncertainty about the self. Issues of self-identity subconsciously come to pervade everything that is done. To regain psychological equilibrium the adolescent is faced with the task of balancing the instinctual wishes of the id against the social demands of the ego. (Anna Freud - Egopsychology).

According to D.W. Winnicott (1965) relative dependence and independence concepts, the child adapts to the external reality in the absence of a mother or secured figure and could develop independence by understanding that himself and the environment can be said to be interdependent.

E-wing sarcoma is a rare tumor that occurs most often in adolescents. Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer must simultaneously navigate the challenges associated with their cancer experience, whilst striving to achieve a number of important developmental milestones at the cusp of adulthood. The disruption caused by their cancer experience at this critical life-stage is assumed to be responsible for significant distress among adolescents and young adults living with cancer. (Ursula M. Sansom-Daly et al; 2013) Adolescents experience physical and psychosocial changes as part of their normal development. It can be reported that they have lower scores on quality of life (Qol) and self-perception when additional changes occur due to cancer treatment. (Christel A.H.P. van Riel et al, 2014 ).

Purpose of this study is to understand the emotional distress related to body image issues when the amputation is only the remediation for the further progression of the cancer to other parts of the body. A Two case series, Pre and Post design, intervention study was adopted. The 2 opposite gender adolescents assessed Cognitive flexibility, Depression, Anxiety, Stress levels by using Neuropsychological testing WCST and DASS for the therapeutic purpose. Brief CBT approach, solution focused therapy, with coping skills and Relaxation training along with family therapy was given as a intervention package. The pre assessment showed Cognitive inflexibility on WCST and moderate levels of Depression, Anxiety, Stress on DASS rating scale. After the 15 sessions of intervention, post assessment results on DASS was found to be nil significant. The two adolescents were observed to be with improved quality of life. They appeared to be stable and prepared for the amputation.

Keywords: E- wings sarcoma; Amputation; Adolescents; Body image issues; Psychological distress

Introduction

Ewing sarcoma is a cancerous tumor was described by Ewing [1], and is a high grade Osteolytic malignant neoplasm. Ewing sarcoma tumor grows in the bones or in the tissue around bones (soft tissue) - often the legs, pelvis, ribs, arms, or spine. It is common in the long bones such as the femur and tibia [2]. It can spread to lungs, bones and bone marrow. Ewing sarcoma tumors include Ewing sarcoma, Askin tumor, Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. These tumors have a similar cellular physiology, as well as a shared chromosomal translocation. It is the third commonest primary malignant bone tumor, after multiple myeloma and osteosarcoma. Among children and young adults, it is the second in frequency after osteosarcoma, and in the population under the age of 15 years, it is the most frequent type [3-6]. Cases are mainly diagnosed in the second decade of life, while 20-30 % are in the first decade, and occurrences are rare in individuals over the age of 30 years and under the age of 5 years [7].Biology of Ewing sarcoma

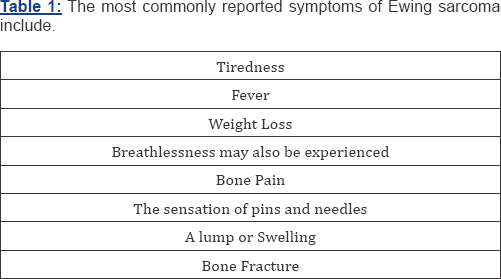

The translocation of the chromosome i.e a part of the chromosome has broken off and stuck to the wrong chromosome. This put genes in the wrong order and can mean that genes are switched on and off incorrectly. A translocation takes place which incorrectly sticks 2 genes together to make a "Fusion gene” known as EWS - FLI1. The production of EWS - FLI1 will causes tumor cells to behave differently and grow abnormally leading to development of cancer. The presence of EWS - FLI1 is help to confirm the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma.[Table 1].

Treatment for Ewing sarcoma

a. Chemotherapy

b. Radiation therapy

c. Surgery

d. Stem cell transplantation/ bone marrow transplantation

Psychological Distress in Adolescents Diagnosed with Ewing Sarcoma

Clinical Distress: Across the studies examined clinical levels of distress was variously defined as meeting criteria for the diagnosis of a mental disorder (eg; PTSD) scoring a highly enough or beyond a clinical cut off score on a particular measure (eg; anxiety, fatigue, depression). The most common manifestations of this distress include grief reactions, anxiety, pre occupation with body image issue. Social isolation and withdrawal are common consequences, and long term difficulties with social and occupational adjustment [8,9]. Care givers are also susceptible to psychological impairment and poor health (Dennis J; 1991). Thus addressing the psychological challenges facing amputees and their families is essential and can, in fact, have more importance than the quality of the surgery or the choice of prosthetic device [10]. This study was mainly intended to focus on the factors influencing psychosocial adjustment to amputation and to bring psychological adaptation towards it.

Depression: Depressive disorders comprise a group of clinical syndromes marked by a constellation of affective, cognitive, neuro-vegetative, and behavioral signs and symptoms. A minority of patients becomes clinically depressed after receiving a diagnosis of adult-onset cancer and during its active treatment, and a larger number of patients experience some depressive symptoms such as sadness, fatigue, or insomnia [11-14].

Anxiety: Anxiety is a complex phenomenon with cognitive, somatic, arousal and behavioral aspects. Cognitive features (e.g., worry, rumination, distraction), somatic symptoms (e.g., rapid heartbeat, sweating, butterflies-in-the-stomach), central nervous system arousal (e.g., hypervigilence, insomnia) and anxiety-related behavioral aspects (e.g., fidgeting, muscle tension, avoidance) can be present singly or in combination. Anxiety tends to be greatest during the initial period of diagnosis and treatment and tends to decline during periods when there is no evidence of illness and no active ongoing treatment [15,16]. During the diagnosis phase of a patient's illness, anxieties may focus on prognosis and treatment options. Body image distortion and body image anxiety occur among some people who have amputation.

PTSD: one research studied patients who had been treated with initial limb salvage procedures for locally advanced Soft tissue sarcoma, Limb salvage was successful in 30 of the patients, but 9 patients had to undergo a subsequent amputation due to either complications of treatment or disease progression. PTSD symptom scores reached clinical significance in 20.5% of the STS patients [17].

Body Image: According to study, "Oncology patients not only have to face a life-threatening disease; they also have to undergo treatments that, by modifying the body image, add more distress to an already compromised emotional situation”[18]. Emotionally detrimental body image perceptions profoundly affect physical and social well-being. [19] found that if adolescents think, they look bad, they feel bad physically

Amputation: Limb Loss is defined as the experience of parting with a limb of the body [20]. Individuals perceive the loss of body part affecting various aspects of their well being which is a devastating occurrence [21]. Those Individuals who experience Lower Limb amputation has significantly more concern with Body Image and Impaired Quality of life [22].

Method

Participants Information

Clients were referred by the Oncology department for to prepare them at preoperative stage, since the tumor was getting metastasis to Femur bone Oncologist had discussed by providing complete information to family members about the process and need of amputation. Family members were agreed, and the same was discussed with the pre-teens. Since after they were in denial for surgery. After understanding the factors which were influencing the psychological adaptation. integration of various psychotherapeutic techniques from Brief CBT approach, solution focused therapy, with coping skills and relaxation training along with family therapy was given as a intervention model to get prepare for the process.

Measures

Distress Thermometer and Screening Tool

Distress screening is a comprehensive process that achieves the quality care standard of whole-patient care, which is the integration of both psychosocial and biomedical cancer care. The NCCN recommends using the validated Distress Thermometer (NCCN-DT), a visual analogue scale that allows patients to rate their perceived level of distress in the last 7 days on a scale of 0 ("no distress”) to 10 ("extreme distress”). Patients clarify the source of distress using a 39-item problem list with 5 categories: practical, family, emotional, spiritual/ religious, and physical. A providers to further assess identified patients and their need for score of 4 or greater has been established as the cutoff point for treatment. [Table 2].

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)

The DASS is a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress. The DASS was constructed not merely as another set of scales to measure conventionally defined emotional states, but to further the process of defining, understanding, and measuring the ubiquitous and clinically significant emotional states usually described as depression, anxiety and stress. In addition to the basic 42-item questionnaire, a short version, the DASS21, is available with 7 items per scale. The Depression scale assesses dysphoria, hopelessness, devaluation of life, self-deprecation, lack of interest/involvement, anhedonia, and inertia. The Anxiety scale assesses autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, situational anxiety, and subjective experience of anxious affect. The Stress scale is sensitive to levels of chronic nonspecific arousal. It assesses difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, and being easily upset/agitated, irritable/over-reactive and impatient. Subjects are asked to use 4-point severity/frequency scales to rate the extent to which they have experienced each state over the past week. Scores for Depression, Anxiety and Stress are calculated by summing the scores for the relevant items. (Psychology foundation of Australia, 2014).

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (West)

It is a neuropsychological testing of "set shifting”, i.e. the ability to display flexibility in the face of changing schedules of reinforcement. The WCST was written by David A. Grant and Esta A. Berg (1948). The Professional Manual for the WCST was written by Robert K. Heaton, Gordon J. Chelune, Jack L. Talley, Gary G. Kay, and Glenn Curtiss. A number of stimulus cards are presented to the participant. The participant is given cards to sort based on color, form, or number, but the participant is not told which of the three criteria to use. however, he or she is told whether a particular match is right or wrong. The original WCST used paper cards and was carried out with the experimenter on one side of the desk facing the participant on the other. The test takes approximately 12-20 minutes to carry out and generates a number of psychometric scores, including numbers, percentages, and percentiles of: categories achieved, trials, errors, and perseverative errors.

Design

A Two case profiles, pre and post design was used to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention.

Procedure

The pre assessment was carried out followed by the presenting complaints, clinical observation. Based on the results obtained from testing's and the need of amputation, by understanding the determinants, combination of different psychotherapeutic techniques integrated as a model. The intervention process was formulated for 15 sessions, which were held twice in a week, each session lasting for 45 minutes. All the 15 sessions were conducted in an inpatient ward setting followed by the post assessment.

Results

The Psychological and Neuropsychological profiles of the two clients, revealed increased levels of distress in emotional and physical aspects, stress, anxiety, depression, on WCST considerable rigidity of thinking and problems with abstraction and conceptual thinking.

The Post assessment results revealed marked improvement qualitatively and quantitatively on Distress screening and DASS. On WCST according to the NIMHAN'S Neuropsychological battery norms both of the patients showed considerable rigidity of thinking and problems with abstraction and conceptual thinking. [Table 3,4].

Therapeutic Techniques

Psycho Education

Disorder specific given by clinical expert to patient & /or his or her family members to learn knowledge and skills , and long term plan management of issues related to illness as well as psychosocial adjustment-apart of the overall treatment plan and includes communication treatment plan. Hatfield (1988) the value of the psycho part psycho education is just as informative and less confusing.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Cbt)

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is based on the interrelationship of thoughts, actions, and feelings. In order to work with feelings of depression, this model establishes the importance of identifying the thoughts and actions that influence mood. In this manner the person learns to gain control of his/her feelings. (Ricardo F. Muñoz, et al. 2007)

Solution-Focused Brief Therapy

SFBT helps clients develop a desired vision of the future wherein the problem is solved, and explore and amplify related client exceptions, strengths, and resources to co-construct a client-specific pathway to making the vision a reality. Thus each client finds his or her own way to a solution based on his or her emerging definitions of goals, strategies, strengths, and resources (Corey, 1985).

Coping Skills Training

Lazarus and Folkman [23] identified two types of coping strategies: problem-focused strategies that are intended to ameliorate the causes of stress, and emotion-focused strategies that are intended to ameliorate stress-induced emotions. Choosing the right treatment team is an example of a problem- focused strategy, while using mental imagery to relax is an example of an emotion-focused strategy

Relaxation Training

Relaxation can help to relieve the symptoms of stress. Although the cause of the anxiety will not disappear, but probably feel more able to deal with it, once one have released the tension in body and cleared the thoughts. Jacobson's progressive relaxation technique involves contracting and relaxing the muscles to make person feel calmer. It is a skill that needs to be learned and it will come with practice. Once one have mastered it will be able to use it throughout one's life.

Family Therapy

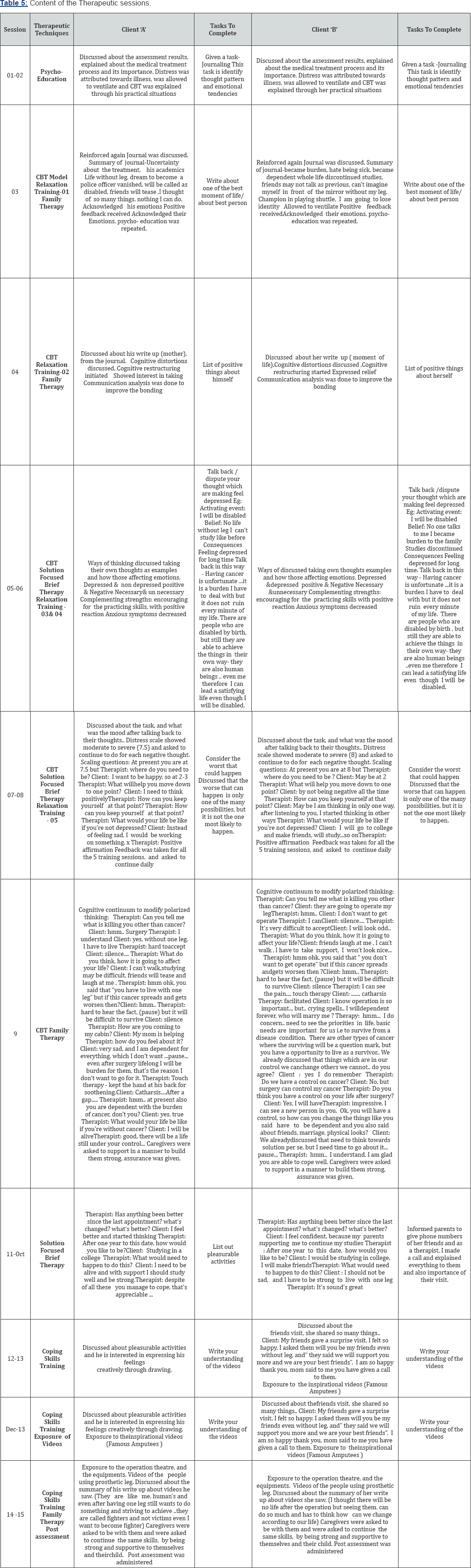

Family therapy is helpful for identifying needed changes within the family system. These changes may include improving communication skills and family interactions and increasing support among family members. Primary goal was to enhance the growth potential of the individual (self actualization) and also to integrate the needs of each individual family member for independent growth with the integrity of the family system (Satir & Baldwin, 1983) [Table 5].

Discussion

The study was done to understand the factors related to body image issue in two opposite genders secondary to amputation, and also to evaluate the efficacy of intervention for the preparation of Amputation. The Two patients of opposite gender, have presented a different scenario in explaining about their fear about Amputation. In the beginning sessions they were in a denial stage towards Amputation, and it was absolutely normal reaction [24].

According to many studies the Anxiety would arise and persistent at different stages of symptoms, and treatment for the cancer (National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN - 2008). Even the same situation in these patients and their concerned families, they were in a state of mixed depression and anxiety due to the change in treatment modality, which was a shock, unexpected and has to undergo mandatory process i.e Amputation.

If amputation is taken as a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or disease process in the affected limb [25]. In these cases amputation cannot be avoided as it is difficult to control the progression of cancer. Individuals with an amputation are faced with adapting to several losses and changes to their lifestyle, social interactions and identity 24. From another perspective 26 see body image in a person as a dynamic changing phenomenon, it is formed by feelings and perceptions about a person's body that are constantly changing [26]. Meanwhile, amputation results in disfigurement and may lead to a negative body image and potential loss of social acceptance 27. Public attitudes toward disability rather than the existence of impairments alone, negatively affect feelings of well being among individuals with disability28. There are many factors that have been investigated in moderating a person's psychological adjustment to losing a limb including patient demographics such as age, gender and level of education 29.

Following an amputation, individuals must adapt to changed physical and social functioning and incorporate these changes into a new sense of self and self identity 24. To sustain their self and self identity the psychological support has to be provided by the Psycho - Oncologist or Clinical Psychologist right from the diagnosis and has to travel along with the patient's journey with the support of family members holistically as a part of multidisciplinary approach. This step will build the trust and the amount of distress can be minimized through serial monitoring. In the cases of surgery, preparation is the most prominent step, during the preoperative stage if the patient's distress is at clinical level of diagnosis then understanding the cognitive triad i.e. perception towards the cancer and its treatment, his/ her life, Prognostic factors [27,28]. This process of preparation will develop the ability to cope with post operative anxiety and depression. During the period shortly after amputation 24 say depression has been reported as being the reason for decreased use of their prosthesis and lower level of mobility amongst people with long term amputations. There is a process of adjustment to prostheses, which also demonstrated the individuality of a person's relationship to it [29].

Conclusion

Amputation is a traumatic event for the young adults and their family members with numerous psychological and physical consequences. In a situation of mandatory surgical amputation, where to control the progression of cancer the priority would be for the fundamental but most crucial concept i.e survival. Because of this the patients and their family members are at risk for a difficult psychological adjustment, thus attention should be directed to the preoperative period to diminish the long term complications. The present study is intended to build the process of reestablishing their sense of self as a whole person. The results were positive qualitatively and quantitatively and the patients were observed to be stable and prepared for the amputation.

References

- Ewing J (1921) Diffuse endothelioma of Bone. Proceedings of the New York Pathological Society 21: 17-24.

- Miser JS, Goldsby RE, Chen Z, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al. (2007) Treatment of metastatic Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone: evaluation of increasing the dose intensity of chemotherapy-a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 49(7): 894-900.

- Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB (2008) Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30(6): 425-430.

- Leavey PJ, Mascarenhas L, Marina N, Chen Z, Krailo M, et al. (2008) Prognostic factors for patients with Ewing sarcoma (EWS) at first recurrence following multi-modality therapy: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51(3): 334-338.

- Li S, Siegal GP (2010) Small cell tumors of bone. Adv Anat Pathol 17(1): 1-11.

- Scotlandi K, Remondini D, Castellani G, Manara MC, Nardi F, et al. (2009) Overcoming resistance to conventional drugs in Ewing sarcoma and identification of molecular predictors of outcome. J Clin Oncol 27(13): 2209-2216.

- Bernstein M, Kovar H, Paulussen M, Randall RL, Schuck A, et al. (2006) Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors: current management. Oncologist 11(5): 503-519.

- Thompson OM, Haran O (1985) Living with an amputation: the helper Soc Sci Med 20(4): 319-323.

- Thompson OM, Haran O (1984) Living with an amputation: what it means for patients and their helpers. Int J Rehabil Res 1984; 7: 283292.

- Friedmann LW (1978) The psychological rehabilitation of the amputee. Springfield: Charles C Thomas.

- Polsky D, Doshi JA, Marcus S, Oslin D, Rothbard A, et al. (2005) Longterm risk for depressive symptoms after a medical diagnosis. Archives of Internal Medicine 165(11): 1260-1266.

- Morasso G, Costantini M, Viterbori P, Bonci F, Del Mastro L, et al. (2001) Predicting mood disorders in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 37: 216-223.

- Massie MJ, Popkin MK (1998) Depressive disorders. In Psychooncology (1998). Holland JC, Breitbart W, Jacobsen PB, Lederberg MS, Loscalzo M, Massie MJ, McCorkle R (Eds.) Oxford University Press, New York, USA, pp. 518-540.

- Massie MJ (2004) Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 32: 57-71.

- Stark DPH, House A (2000) Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 83(10): 1261-1267.

- Vant Spijker A, Trijsburg RW, Duivenvoorden HJ (1997) Psychological Sequelae of Cancer Diagnosis: A Meta-analytical Review of 58 Studies after 1980. Psychosom Med 59(3): 280-293.

- Thijssens KMJ, Hoekstra Weebers JEHM, Van Ginkel RJ, Hoekstra HJ (2006) Quality of life after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion for locally advanced extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann of Surg Oncol 13(6): 864-871.

- Annunziata MA, Giovannini L, Muzzatti B (2011) Assessing the body image: Relevance, application and instruments for oncological settings. Support Care Cancer 20: 901-907.

- Williamson H, Harcourt D, Halliwell E, Frith H, Wallace M (2010) Adolescents' and parents'experiences of managing the psychological impact of appearance during cancer treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 27(3): 168-175.

- Crosby L, Miller C (1999) Body Image, Self esteem and Quality of Life in older individuals with lower limb amputations. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 28(3): 113.

- Cleveland J, Vanicek N, Polman RC (2013) Temporal adaptations in generic and population specific quality of life and fall efficacy in men with recent lower limb amputations 50(3): 437-448.

- Lauren V Fortington, Rommers GM, Geertzen JH, Postema K, Dijkstra PU (2012) Mobility in Elderly People With a Lower Limb Amputation: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13(4): 319-325.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York.

- Horgan O, Maclachlan M (2004) Psychosocial adjustment to lower-limb amputation: a review. Disabil and Rehabil 26(14-15): 837-850.

- Wald J (2004) Psychological factors in work-related amputation: Consideration for rehabilitation counsellors. Journal of rehabilitation 70(4): 6-15.

- Flannery CJ, Faria HS (1999) Limb Loss: Alterations in body image. J Vasc Nurs pp.100-106.

- Jacobsen MJ (1998) Nursing role with amputee support groups. J Vasc Nurs 16(2): 31-34.

- Green ES (2007) Components of perceived stigma and perceptions of well-being among university students with and without disability experience. Health Sociology Review 16(3-4): 328-340.

- Saradjian A, Thompson RA, Datta Dipak (2008) The experience of men using an upper limb prosthesis following amputation: Positive coping and minimizing feeling different. Disabil Rehabil 30(11): 871-883.