Haryana- Hotspot of Hepatitis B in India

Parveen Malhotra*, Vani Malhotra, Paramjeet Singh Gill, Pushkar, Usha Gupta and Yogesh Sanwariya

Department of Medical Gastroenterology and Microbiology, Gynecology & Obstetrics, India

Submission:March 30, 2021; Published:April 26, 2021

*Corresponding author:Parveen Malhotra, Department of Medical Gastroenterology and Microbiology, Gynecology & Obstetrics, PGIMS, Rohtak & Director Health Services, Haryana, 128/19, Civil Hospital Road, Rohtak, Haryana, India

Abbreviations: Parveen M, Vani M, Paramjeet S G, Pushkar, Usha G, Yogesh S. Haryana- Hotspot of Hepatitis B in India. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol, 2021; 16(5): 555947.. DOI: 10.19080/ARGH.2023.16.555947.

Abstract

Introduction: Approximately one third of the world’s population has serological evidence of past or present infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV). An estimated 350-400 million people are surface HBV antigen (HBsAg) carriers. Thus, HBV infection is one of the most important infectious diseases worldwide. India is facing major burnt of this deadly disease and has 40 million HBV carriers i.e., 10-15% share of total pool of HBV carriers of the world. In India, 100,000 patients die due to HBV infection.

Aims and Objectives: To determine epidemiological profile, clinical presentation, risk factors, co-infection, use of alternative medications, need and compliance on antiviral treatment in patients of Hepatitis B virus infection.

Materials and Methods:This retrospective study was done at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak over a period of ten years i.e., 01.09.2010 to 31.08.2020, on all HbsAg positive patients who reported for consultation and treatment on outdoor basis i.e., on OPD basis who were not admitted or were admitted in indoor wards of hospital. In our study total 4850 patients were identified but 22 patients refused to get enrolled in the study, hence total 4828 patients were finally enrolled and their records were collected regarding their detailed epidemiological profile and clinical spectrum. In accordance with estimated prevalence of Hepatitis B in Haryana, sample size was calculated. At inclusion time, detailed history of the patient was recorded, clinical examination and detailed investigations were done

Conclusion:Hepatitis B is a major health issue in India with non-uniform distribution and certain geographical areas are hotspots like Haryana. The young males belonging to rural background are most vulnerable due to lack of safe injection practices and proper health care facilities. Majority of patients of Chronic hepatitis B are in inactive stage, thus not requiring treatment but on regular follow up. Only 10% of patients presented with acute hepatitis B. The history of use of parenteral injections, surgical interventions and dental procedures has been found to be important risk factor. We cannot rely on blood bank data for determining the prevalence of it but screening of high-risk population in at least hotspots will reflect true picture. Moreover, it will lead to early detection of cases and thus will substantially decrease the development of long-term complications like cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as shown in our this study.

Keywords:Hepatitis B virus; Safe injection practices; Health care facility; Co-infection; Cirrhosis HBV DNA

Introduction

Approximately one third of the world’s population has serological evidence of past or present infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV). An estimated 350-400 million people are surface HBV antigen (HBsAg) carriers [1,2]. Thus, HBV infection is one of the most important infectious diseases worldwide. Around one million persons die of HBV-related causes annually. There is a wide range of HBV prevalence rates in different parts of the world. HBV prevalence varies from 0.1% up to 20%. Low prevalence (<2%) areas represent 12% of the global population and include Western Europe, the United States and Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In these regions, the lifetime risk of infection is less than 20%. Intermediate prevalence is defined as 2% to 7%, with a lifetime risk of infection of 20-60% and includes the Mediterranean countries, Japan, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Latin and South America, representing about 43% of the global population. High prevalence areas (≥8%) include Southeast Asia, China, and sub-Saharan Africa, where a lifetime likelihood of infection is greater than 60%. The diverse prevalence rates are probably related to differences in age at infection, which correlates with the risk of chronicity. The progression rate from acute to chronic HBV infection decreases with age. It is approximately 90% for an infection acquired perinatally and is as low as 5% for adults [3,4]. In all the cases of chronic hepatitis B (HBV) infection,15-40% will develop cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma [5-8].

The incidence of new infections has decreased in most developed countries, most likely due to the implementation of vaccination strategies [9]. However, exact data is difficult to generate as many cases remain undetected due to the asymptomatic nature of many infections [10]. India harbors around 40 million HBV carriers, thus accounting for 10-15% share of total pool of HBV carriers of the world. Every year over 100,000 Indians die due to illnesses related to HBV infection [11,12] and HBsAg positivity ranges between 2-4.7% [13,14]. Hepatitis B being a major public health problem in India has been included in National Viral Hepatitis Control Program but there is lacunae of large scale studies on hepatitis B in India which are essential for developing future preventive and treatment strategies, to curb the menace of this deadly disease. Hence, in light of above explained ground situation, our study was done. Age of acquisition of the virus, immune competence of the host and the strength of immune response to the viral antigens are some of the determinants of timing and efficiency of seroconversion. If significant liver damage is already present at time of seroconversion, then prognosis is not good. On the other hand, if the seroconversion had occurred early and is maintained, then the long-term prognosis is excellent. Since majority of infected people remain asymptomatic thus early diagnosis is critical for timely initiation of treatment for viral hepatitis B. Routine assessment of HbsAg-positive persons is needed to guide HBV management and indicate the need for treatment. The serum HBV DNA levels and grade of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis are used for decisions to treat and subsequent monitoring. Antiviral agents against HBV are easily available, with minimal resistance, effective in suppressing HBV replication, prevent progression to cirrhosis, and reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (H.C.C) and liver-related deaths but fail to eradicate the virus in most of those treated, thus lifelong treatment is usually required. The preventing strategies include needle exchange in people who injects drugs (PWID), barrier contraception in persons who inject drugs, men who have sex with men and sex workers, prevention of HBV transmission through immunization of health care workers, voluntary blood donation and universal screening of blood and blood products before transfusion. All pregnant women should be screened for with HBV infection and positive ones should be evaluated for treatment and if indicated should be started on antiviral treatment from seventh month of pregnancy. Only a small subset of these patients will require treatment. The steps for prevention of transmission of HBV infection should always be taken like hospital-based delivery, so that all infants born to HBV positive women need are immunized and administered Hepatitis B immunoglobulin within 24 hours of birth. The natural history of HBV infection consists of five phases: the immunotolerant phase, the immune reactive HBeAg positive phase, the inactive HBV carrier phase, the HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B phase and the HBsAg negative phase or resolution phase [15]. The Patients are never treated in immunotolerant phase, as virus is not having any ill effects on human body and unwarranted prolonged treatment will lead to development of drug resistance. The treatment is started in immune reactive phase when there is evidence of disease activity as evidenced by high HBV DNA viral load, persistently raised transaminases or significant fibrosis on liver biopsy or non-invasive methods like APRI, FIB 4 score or Fibroscan score of more than 8.2. The risk of HBV infection may be higher in HIV/HCV-infected adults, and therefore all persons newly diagnosed with HIV/HCV should be screened for HbsAg and immunized if HbsAg is negative.

Aim and Material & Methods of Study

Study type: This was retrospective study for determining Epidemiological profile, Clinical presentation, risk factors, Coinfection, use of alternative medications, need and compliance on antiviral treatment in patients of Hepatitis B virus infection.

Study setting: The study was done at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana over a period of ten years i.e., 01.09.2010 to 31.08.2020.

Data collection: In this retrospective study, all hepatitis B patients who reported for consultation and treatment at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana in last ten years, and consented for enrollment in the study, their records were collected regarding their epidemiological profile, clinical presentation, risk factors, co-infection, use of alternative medications, need and compliance on antiviral treatment. In our study total 4850 patients were identified but 22 patients refused to get enrolled in the study, hence total 4828 patients were finally enrolled. At inclusion time, detailed history of the patient was recorded like age, gender , residence, when hepatitis B detected , past history of any blood transfusion, surgery, needle stick injury, dental procedure, tattooing, acupuncture, unprotected intercourse with multiple sexual partners, intravenous drug abuse, history of previous upper GI bleed, hepatic encephalopathy, melena, history of other co morbidities like diabetes, hypertension, HIV, hepatitis C, chronic kidney disease, thyroid dysfunction. After that detailed clinical examination was done which included measurement of height, weight, BMI, complete general examination, tattoo, needle or puncture marks, icterus, stigmata of liver disease, organomegaly, ascites and systemic examination was done. The laboratory investigations done included complete hepatitis B profile, anti- HIV and HCV antibody, complete blood counts, liver and Kidney function tests, serum electrolytes, blood sugar, ultrasonogram abdomen, chest x ray PA view, and where indicated, ascitic fluid analysis, alpha fetoprotein level, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, Triple phase computed tomography scan of abdomen and Fibro scan.

Study variables: The study variables were age, gender, rural or urban background, pregnancy, clinical stage of disease, risk factors, use of alternative medications.

Data processing and statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was performed by the SPSS program version 25.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median (range), and categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers and percentage. Data was checked for normality before statistical analysis using Shaipro Wilk test. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test or ANOVA with appropriate post hoc tests. The Kruskal Wallis test was used for those variables that are not normally distributed and further comparisons will be done using Mann Whitney U test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi square test. For all statistical tests, a p value less than 0.05 was taken to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Background characteristics

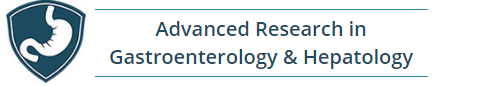

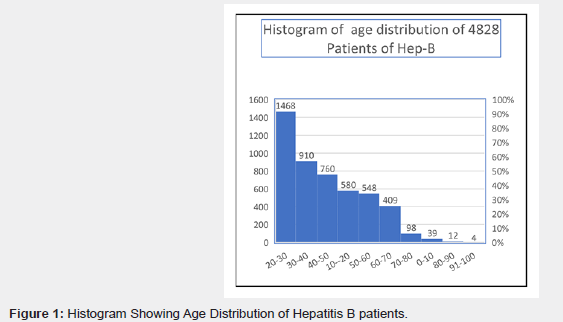

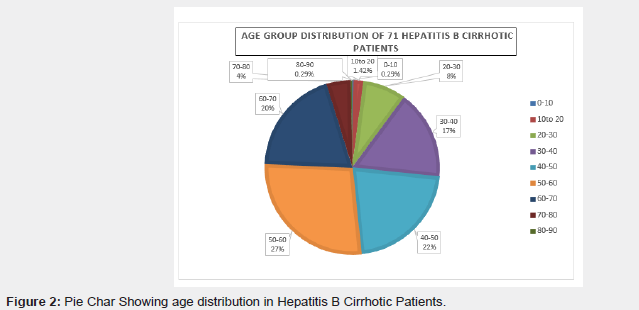

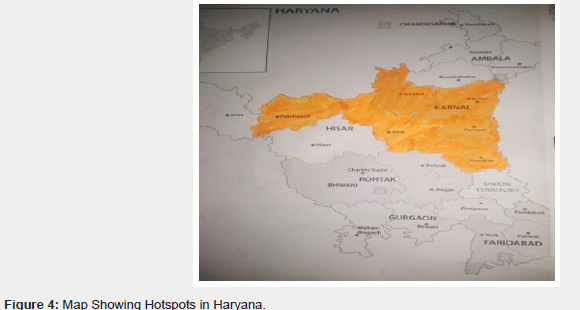

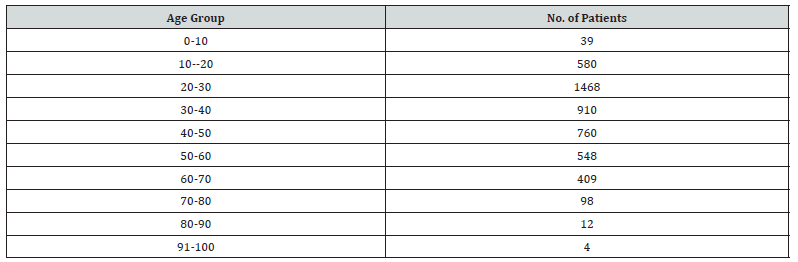

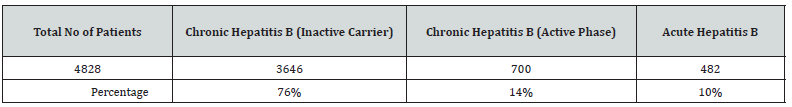

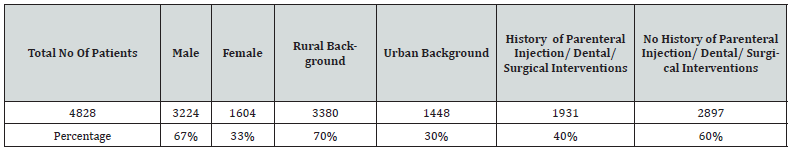

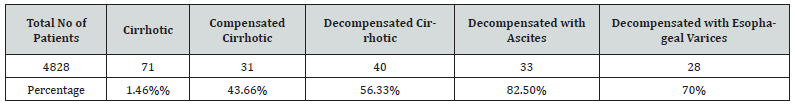

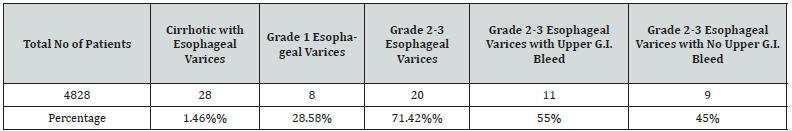

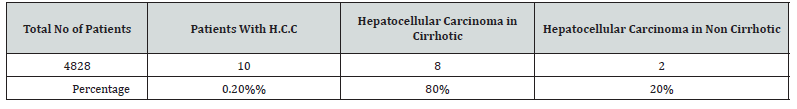

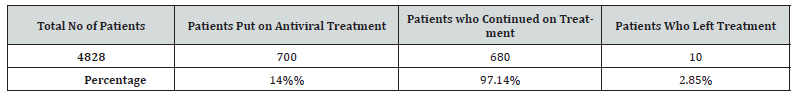

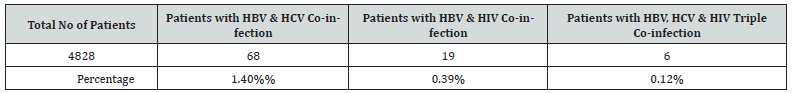

In our study total 4850 patients were identified but 22 patients refused to get enrolled in the study, hence total 4828 patients were finally enrolled and data pertaining to them was analyzed. The age distribution was from 1-100 yrs of age and maximum number of patients were between 20-50 yrs of age group (65%) with minimal representation from extremes of ages. When sex distribution was analyzed then strikingly 3224 patients (67%) were males and only 1604 patients (33%) were females. On analysis of socio-economic background, 3380 patients (70%) were from rural background with poor socio-economic status and rest 1448 patients (30%) belonged to urban population with proper standard of living. In our study, 40% (1931) patients gave history of Parenteral injections, dental or any other surgical interventions & tattooing. Around 148 patients (3.06%) were detected during blood donation and out of total pool of 4828 patients, 70 pregnant females were found positive for HbsAg. There are certain districts of Haryana state like Jind, Kaithal, Panipat, Karnal, Sonepat which were found to be hotspots for hepatitis B, as maximum number of patients belonged to these districts (Figure 1). On analysis of clinical stages of diseases, out of total 4828, maximum number of hepatitis B patients were chronic hepatitis B but in inactive carrier state i.e., 3646 patients (76%) and did not require any treatment. In total 700 patients (14%) of chronic hepatitis B were found to be in active phase and were started on treatment. In total pool of 4828 patients, only 1.47% were found to be cirrhotic and on analyzing in treatment group, then out of total 700 patients who required treatment, the contribution of these 71 patients is around 10.14% only. In these 71 cirrhotic patients, 52 (73.23%) were males and 19 (26.26%) were females. On analysis of age distribution, the percentage of cirrhotic patients increased with increasing age and maximum were seen in 30 yrs-70 years age group (84%) with peak in 50-60 years of age (27%). Out of these 71 cirrhotic patients, 31 patients (43.66%) were in compensated stage and 40 patients (56.33%) had already decompensated. Out of this total pool of 40 decompensated cirrhotic patients, 33 patients (82.50%) had ascites and 28 patients (70%) had esophageal varices. In this pool of 28 patients with esophageal varices, 8 patients (28.57%) had grade 1 esophageal varices and rest 20 patients (71.42%) had grade 2 & grade 3 varices. Out of these 20 patients with grade 2 & 3 varices, 11 patients (55%) presented with upper gastrointestinal bleed. In total pool of 4828 patients, only 10 patients (0.20%) developed H.C.C. and out of them, eight had cirrhosis and two were non-cirrhotic but were in active phase. In 700 patients (14%) who were found to be in active phase and treatment was started, 34 patients (4.85%) were of chronic kidney disease (Figures 2 & 3). The acute hepatitis B state was seen in 482 patients i.e., 10% of total patients of hepatitis B (Figure 4). In our study, HBV & HCV coinfection was seen in 68 patients (1.40%), HBV & HIV co-infection in 19 patients (0.39%) and HBV, HCV &HIV triple co-infection in 6 patients (0.12%). Out of the total pool of 4828 patients, 2028 patients (42%) gave history of use of alternative medications for treatment of hepatitis B infection. This percentage substantially increased on selective analysis of 482 patients of acute hepatitis B in which 350 patients (85.57%) used alternative medications. Out of total 700 patients who were put on antiviral treatment, only 20 patients (2.85%) left treatment in between due to switching back to alternative medications or feeling no need of continuing with therapy in view of good health (Tables 1-9).

Discussion

In our study, the age distribution varied between 1-100 years of age and characteristically showed predominance of patients between 20-50 years of age group with highest peak in 20-30yrs of age. Out of total pool of 4828 patients, 3224 patients (67%) were males and 70% (3380 patients) of patients belonged to rural background with lower socioeconomic status. There was significant percentage of patients i.e., 40% (1931 patients) who had history of Parenteral injections, dental or any other surgical interventions & tattooing. The disease pattern is not uniform in state of Haryana and there are certain districts like Jind, Kaithal, Panipat, Karnal, Sonepat which were found to be hotspots for hepatitis B, as maximum number of patients belonged to these districts. The patients from all the districts come for treatment at our department, as it is sole Government set up providing free treatment. Moreover, screening camps are also held regularly at all the districts and maximum number of patients were detected in same districts. This was the basis of identification of these hotspots. Surprisingly, all these districts are also hotspots for chronic hepatitis C. Out of the total pool of 4828 patients, 2028 patients (42%) gave history of use of alternative medications for treatment of hepatitis B infection. This percentage substantially increased on selective analysis of 482 patients of acute hepatitis B in which 350 patients (85.57%) used alternative medications. The maximum number of hepatitis B patients were chronic hepatitis B but in inactive carrier state i.e., 3646 patients (76%) thus not requiring treatment but regular follow up. In total 700 patients (14%) of chronic hepatitis B were found to be in active phase or cirrhotic and were started on treatment. In total pool of 4828 patients, only 71 patients (1.46%) were found to be cirrhotic and on analysis in treatment group, then out of total 700 patients which required treatment, the contribution of these 71 patients is around 10.14% only. In these 71 cirrhotic patients, 52 (73.23%) were males and 19 (26.26%) were females. On analysis of age distribution, the percentage of cirrhotic patients increased with increasing age and maximum were seen in 30 yrs-70 years age group (84%) with peak in 50-60 years of age (27%). Out of these 71 cirrhotic patients, 31 patients (43.66%) were in compensated stage and 40 patients (56.33%) had already decompensated. Out of this total pool of 40 decompensated cirrhotic patients, 33 patients (82.50%) had ascites and 28 patients (70%) had esophageal varices. In this pool of 28 patients with esophageal varices, 8 patients (28.57%) had grade 1 esophageal varices and rest 20 patients (71.42%) had grade 2 & grade 3 varices. Out of these 20 patients with grade 2 & 3 varices, 11 patients (55%) presented with upper gastrointestinal bleed. Out of total 4828 patients, only 10 patients (0.20%) developed hepatocellular carcinoma. Out of these ten patients, eight had cirrhosis and two were non-cirrhotic. In 700 patients (14%) who were found to be in active phase and treatment was started, 34 patients (4.85%) were of chronic kidney disease. India is in intermediate zone of HBV prevalence and harbors about 40 million asymptomatic hepatitis B virus carriers [13-15] and same has been corroborated in study done by Malhotra etal,2020 in which yearly prevalence of HbsAg ranged between 3.16%- 8.1% with mean of 5.23% [16]. The most common carrier rate reported in India is 4.7%. We rely usually on blood bank data for estimating prevalence of hepatitis B infection, but it is fallacious and same fact has been reflected in study by Malhotra etal ,2020, in which blood bank data under estimated prevalence rates of HBsAg and anti-HCV antibody positivity of 0.80% and 0.81% respectively, whereas the rates derived from passive screening data were 5.23% and 5.18% respectively [17]. In our present study also only 148 patients (3.06%) were detected during blood donation. The maximum number of patients are seen in adulthood in Indian population and it suggests close relationship of acquisition of infection in the adults [18]. The in study conducted by Chaudhary A,2004 estimated 2.97% prevalence of HbsAg and peak occurred after the second decade of life [19]. In our study also, the age distribution varied between 1-100 years of age and characteristically showed predominance of patients between 20-50 years of age group with highest peak in 20-30yrs of age. In an earlier study, frequent exposure to percutaneous injuries, repeated use of Parenteral injections for trivial illnesses and the untrained para-medical personnel, lacking in knowledge about modes of sterilization in primary care centers have been found to be the major factors that facilitate transmission of HBV [17]. In our study also, 40% (1931) patients gave history of Parenteral injections, dental or any other surgical interventions & tattooing. Moreover, 70% (3380 patients) of patients in our group of study came from rural background with lower socioeconomic status and as expected circumstantially they were exposed maximum to unsafe needle practices. The interfamilial aggregation of HBV infected persons has been well documented in India and HbsAg contamination of surfaces is widespread in homes of chronically infected persons [20-22] thus explaining the non-sexual interpersonal spread of HBV such as among household contacts. Our study revealed that certain districts in Haryana state like Jind, Kaithal, Panipat, Karnal, Sonepat are hotspots for hepatitis B, as maximum number of patients belonged to these districts. Surprisingly, all these districts have already been reported to hotspots for chronic hepatitis C by Malhotra et al. [23]. The explanation is that both hepatitis B & C are having common route of transmission i.e., blood borne and non-availability of proper health infrastructure thus leading to unsafe needle practices. The HBV infection is most commonly seen in adult patients in the third or fourth decade of life and are more frequently males [24]. In our study also there was male predominance strikingly 3224 patients (67%) were males. The spectrum of liver damage ranges from mild (approximately 20 to 40%) to moderate or severe chronic hepatitis (approximately 40 to 60%) or active cirrhosis (approximately 10 to 25%) [25]. In about two-thirds of the disease burden in India, it is represented by inactive/immunotolerant phase thus not requiring any treatment [26,27]. Our study also confirms the same findings, as 76% were chronic hepatitis B but in inactive carrier state thus not requiring any treatment. Only 14% of chronic hepatitis B were found to be in active phase or cirrhotics and were started on treatment. Only1.46% were found to be cirrhotic and on analyzing in treatment group, then out of total 700 patients which required treatment, the contribution of these 71 patients is around 10.14% only. Out of these 71 cirrhotic patients, 31 patients (43.66%) were in compensated stage and 40 patients (56.33%) had already decompensated. Out of this total pool of 40 decompensated cirrhotic patients, 33 patients (82.50%) had ascites and 28 patients (70%) had esophageal varices. In this pool of 28 patients with esophageal varices, 8 patients (28.57%) had grade 1 esophageal varices and rest 20 patients (71.42%) had grade 2 & grade 3 varices. Out of these 20 patients with grade 2 & 3 varices, 11 patients (55%) presented with upper gastrointestinal bleed. The male predominance was also seen in cirrhotic group which is also on expected lines with more representation of them in total pool of 4828 patients. The more number of cirrhotic patients in older age is due to the fact that it takes prolonged period of years together for developing cirrhosis. Only 10 patients (0.20%) developed H.C.C. and out of them, eight had cirrhosis and two were non-cirrhotic which emphasizes the fact that hepatitis B virus can directly proceed to H.C.C without passing through cirrhotic stage but in very limited number of patients. The acute hepatitis B state was seen in 10% (1482 patients). In hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) endemic countries, patients are exposed to the risk of being co-infected with both viruses. Parenteral viral transmission could also lead to HCV/HBV coinfection. In patients infected with both HCV and HBV, the risk of developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma is usually higher than those with mono-infection of either virus [28-30]. Therefore, patients co-infected with hepatitis C and B require regular monitoring and aggressive antiviral treatment. In our study, HBV & HCV co-infection was seen in 68 patients (1.40%), HBV & HIV co-infection in 19 patients (0.39%) and HBV, HCV &HIV triple co-infection in 6 patients (0.12%). The characteristic point was that majority of patients of co-infection belonged to hotspots which can be due to common mode of transmission i.e., blood borne. The very minimal percentage of co-infection in such a large group of 4828 patients can be explained on basis of one virus not allowing the survival of another virus in human body which is already well documented in literature. The Haryana Government under the National Viral Hepatitis Control Program (NVHCP) is actively working on Hepatitis B vaccination program under which populations at risk like health care workers, new borns of hepatitis B pregnant mothers, family members of hepatitis B patients, patients suffering from Cirrhosis, hepatitis C, HIV, truck drivers, thalassemia’s, hemophiliacs and dialysis patients are being vaccinated. In 700 patients (14%) who were found to be in active phase and treatment was started, only 34 patients (4.85%) were of chronic kidney disease (CKD). The lesser number of patients in this group is due to hospital policy of non-dialyzing patients suffering from hepatitis B, C or HIV, as there are no separate dialyzing machines for these patients. Hence, there is under reporting of CKD patients in our study group. Out of total 700 patients who were put on antiviral treatment, only 20 patients (2.85%) left treatment in between due to switching back to alternative medications or feeling no need of continuing with therapy in view of good health. The various reasons for this exemplary high compliance rate of 97.15% are easily available free availability of complete treatment including all tests & drugs on daily basis under NVHCP, good connectivity with patients with help of telephonic help line and minimal side effects of antiviral drugs. The minimal number of patients who left treatment in between was due to illiteracy, thus failing to understand the need of proper and regular treatment.

Conclusion

Hepatitis B is a major health issue in India with non-uniform distribution and certain geographical areas are hotspots like Haryana. The young males belonging to rural background are most vulnerable. Majority of patients of Chronic hepatitis B are in inactive stage, thus not requiring treatment but require regular follow up. Only 10% of patients presented with acute hepatitis B. There is huge tendency of using alternative medications as first line of treatment, mainly due to unawareness about severity of illness caused by illiteracy, as it is most seen in poor strata of society who have less access to proper health care facilities. The compliance of patients on antiviral therapy is very good due to easy access of totally free treatment and good bonding with treating team. The history of use of Parenteral Injections, Surgical interventions and Dental procedures has been found to be important risk factor. We cannot rely on blood bank data for determining the prevalence of it but screening of high-risk population in at least hotspots will reflect true picture. Moreover, it will lead to early detection of cases and thus will substantially decrease the development of long-term complications like cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as shown in this study.

Limitation of the Study

The limitation of study is that data pertaining to vertical transmission of Hepatitis B from pregnant mothers to new borns and effect of other comorbid conditions has not been analyzed.

Ethical Approval of the Study

The study was approved by the committee of Pt. B.D. Sharma University of Health Sciences.

References

- Goldstein ST, Zhou F, Hadler SC, Bell BP, Mast EE, et al. (2005) A mathematical model to estimate global hepatitis B disease burden and vaccination impact. Int J Epidemiol 34: 1329-1339.

- (2012) European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 57: 167-185.

- Stevens CE, Beasley RP, Tsui J, Lee WC (1975) Vertical transmission of hepatitis B antigen in Taiwan. N Engl J Med 292(15): 771-774.

- Wasley A, Grytdal S, Gallagher K (2008) Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis-United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ 57(2): 1-24.

- World Health Organization (2012) Hepatitis B. World Health Organization Fact Sheet 204.

- Lavanchy D (2004) Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat 11(2): 97-107.

- Lok AS (2002) Chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 346(22): 1682-1683.

- Goldstein ST, Zhou F, Hadler SC et al. (2005) A mathematical model to estimate global hepatitis B disease burden and vaccination impact. Int J Epidemiol 34: 1329-1339.

- Rantala M, van de Laar MJ (2008) Surveillance and epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in Europe - A review. Euro Surveill 13: 18880.

- (2010) CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Viral Hepatitis Surveillance - United States, Reported number of acute hepatitis B cases- United States, 20002010.

- Dutta S (2008) An overview of molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in India. Virol J 5: 156.

- World Health Organization (2012) Introducing Hepatitis B Vaccine in Universal Immunization Program in India. A Brief Scenario.

- Abraham P (2012) Viral Hepatitis in India Clin Lab Med 32(2): 159-174.

- Thyagarajan SP, Jayaram S, Mohanavalli B (1996) Prevalence of HBV in general population in India. In: Sarin SK, Singal AK, (Eds). Hepatitis B in India: Problems and prevention. CBS, New Delhi, India, p. 5-16.

- (2002) Prevention of Hepatitis B in India - An Overview. World Health Organization South-East Asia Regional Office; New Delhi, India.

- Malhotra P, Malhotra V, Pushkar, Gupta U, Sanwariya Y (2020) Prevalence of hepatitis B and Hepatitis C in Tertiary Care Centre of Northern India. Adv Res Gastro Enterol Hepatol 15(3): 55918.

- Malhotra P, Malhotra V, Gupta U, Gill PS, Pushkar (2020) The Prevalence of Hepatitis B and C among the Passively Screened Population and Blood Donors in Haryana, India: A Retrospective Analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol Lett 2(2): 1-5.

- Chowdhury A, Santra A, Chakravorty R, Banerji A, Pal S (2005) Community-based epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in West Bengal, India: prevalence of hepatitis B e antigen-negative infection and associated viral variants. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20(11): 1712-1720.

- Chowdhury A (2004) Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in India. Hepatitis B Annual p. 17-24.

- Chakravarty R, Chowdhury A, Chaudhuri S, Santra A, Neogi M (2005) Hepatitis B infection in Eastern Indian families: Need for screening of adult siblings and mothers of adult index cases. Public Health 119(7): 647-654.

- Petersen NJ, Barrett DH, Bond WW, Berquist KR, Favero MS (1976) Hepatitis B surface antigen in saliva, impetiginous lesions, and the environment in two remote Alaskan villages. Appl Environ Microbiol 32(4): 572-574.

- Maddrey WC (2000) Hepatitis B: an important public health issue. J Med Virol 61: 362-366.

- Malhotra P, Malhotra N, Malhotra V, Chugh A, Chaturvedi A (2016) Haryana in Grip of Hepatitis C. International Invention Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 3(1): 6-13.

- Fattovich G (2003) Natural history and prognosis of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis 23: 47-58.

- Giovanna Fattovich, Irene Zagni, Chiara Scattolini (2004) Natural History of Hepatitis B and Prognostic Factors of Disease Progression. Management of Patients with Viral Hepatitis, Paris.

- Ray G (2017) Current Scenario of Hepatitis B and Its Treatment in India. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology 5(3): 277-296.

- Balasubramanian S, Velusamy A, Krishnan A, Venkatraman J (2012) Spectrum of hepatitis B infection in Southern India: A cross-sectional analysis. Hepatitis B Annual 9 (1): 4-15.

- Liu CJ, Liou JM, Chen DS, Chen PJ (2005) Natural course and treatment of dual hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. J Formos Med Assoc 104(11): 783-791.

- Chen DS, Kuo GC, Sung JL, Lai MY Sheu et al. (1990) Hepatitis C virus infection in an area hyper endemic for hepatitis B and chronic liver disease: The Taiwan experience. J Infect Dis 162(4): 817-822.

- Liu CJ, Chen PJ, Shau WY, Kao JH, Lai MY (2003) Clinical aspects and outcomes of volunteer blood donors testing positive for hepatitis-C virus infection in Taiwan: A prospective study. Liver Int 23(3): 148-155.