Atypical Presentation of Whippels Disease

Parveen Malhotra*, Vani Malhotra, Sanjay Marwaha, Nisha Marwaha, Abhishekh, Yogesh Sanwariyaa and Nisha

Department of Medical Gastroenterology, Surgery, Pathology, Gynecology & Obstetrics, PGIMS, Rohtak, Haryana, India

Submission:January 01, 2021;Published:January 29, 2021

*Corresponding author:Parveen Malhotra, Department of Medical Gastroenterology, Surgery, Pathology, Gynecology & Obstetrics, PGIMS, 128/19, Civil Hospital Road, Rohtak, Haryana, India

How to cite this article:Parveen M, Vani M, Sanjay M, Nisha M, Abhishekh, et al. Atypical Presentation of Whippels Disease. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol, 2021;16(3): 555939. DOI:10.19080/ARGH.2021.16.555939.

Abstract

Objective:Whipple’s disease, a rare systemic infectious disease, having an annual incidence of 3 in one million, can prove to be fatal if not diagnosed early and treated appropriately.

Clinical Presentation:We present a young male of 18 years who was admitted to the hospital with symptoms of pain abdomen. The diagnosis was made based on colonoscopy and histopathological findings of large intestine biopsies.

Conclusion: Whipple’s disease should be kept behind mind as it may present both with classical as well as atypical features.

Keywords: Whipple’s disease; Tropheryma whipplei; Pain abdomen; Diarrhea; Colonoscopy

Introduction

Whipple’s disease is a very rare, chronic, systemic infectious disease with an annual incidence of 3 in one million, which may be fatal if not diagnosed and treated appropriately [1,2]. Classical Whipple’s disease causes severe weight loss with chronic intermittent diarrhea, colic-like abdominal pain, and migratory polyarthritis or arthralgia in large joints. Rarely, there may be clinical manifestations of isolated central nervous system disease, endocarditis, or lung, skin, or eye disorders [3]. The causative agent of Whipple’s disease, Tropheryma whipplei, is a gram-positive bacillus [3,4]. The mean time between the first symptoms of the patient till the diagnosis of this disease was reported to be 7 years [5]. we present a patient with isolated complaint of Pain abdomen, that too of short duration and was diagnosed with Whipple’s disease within a short time from the onset of symptoms. The disease is severe, and timely diagnosis saved the life of the patient.

Case Report

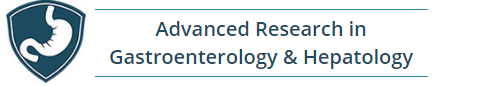

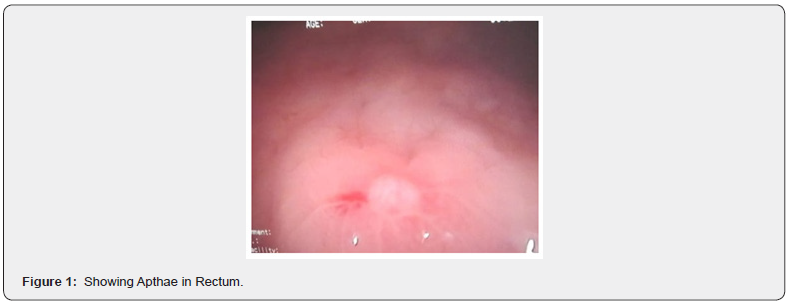

An eighteen-year-old young male from rural background, involved in dairy farming, not a known case of any chronic illness presented with acute pain abdomen of two weeks duration and single episode of diarrhea lasting for two days. He was admitted and underwent urgent ultra-sonogram & Contrast enhanced computed tomographic scan which revealed mesentric lymphadenopathy along with mild appendicular & terminal ileum thickening, with probable diagnosis of acute appendicitis. The pain abdomen was not classical of acute appendicitis; hence colonoscopy was done to rule out Koch’s abdomen. The colonoscopy revealed multiple small apthae in recto sigmoid junction but rest of colon including terminal ileum, cecum & appendicular area were totally normal. The colonoscopic biopsies from apthae on histopathological examination was classical for whippel’s disease.

On physical examination , he was conscious, cooperative, and well built. He was afebrile and all his vital parameters including blood pressure , pulse rate, respiratory rate were normal. The abdominal examination revealed generalized mild tenderness without defense or rebound. His other systemic examination including Neurological, Cardiovascular, Skeletal and opthomological were normal. The Complete haemogram revealed thrombocytosis and Erythrocyte Sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised but liver & renal function tests, serum amylase, thyroid & complete lipid profile, serum iron, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin B 12 & D3 were essentially normal. The stool for occult blood was positive at time of admission. The serological markers for Hepatitis B,C, HIV, celiac disease, and tuberculosis were negative.

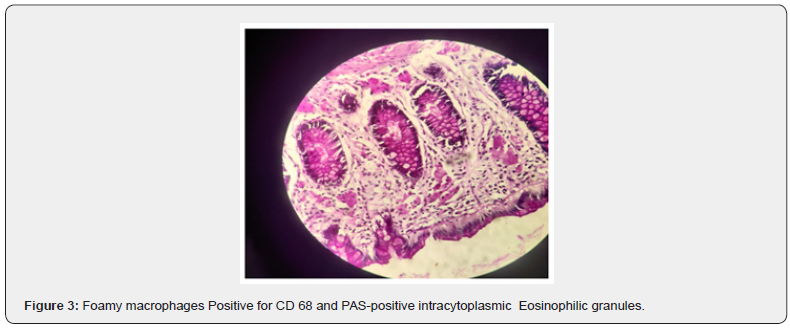

Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography of the abdomen revealed multiple small mesenteric lymph nodes, with largest measuring 9 mm and mild diffuse long segment circumferential mural thickening of Ileal loops in pelvis? Infective. In view of ruling out tubercular abdomen , colonoscopy was done which revealed multiple small apthae in Recto-sigmoid area, the biopsies from which on histopathological examination revealed in lamina propria, the presence of distended foamy macrophages which were histochemically positive for Periodic Acid Schiff stain (PAS) & CD 68, along with mild increase in inflammatory infiltrate. The Zheil Nelson staining (ZN ) for Acid Fast Bacilli was negative.

The findings were consistent with Whipple’s disease. The patient was fully evaluated for determining ,the involvement of other organs and his Echocardiography, Electrocardiogram, Chest and upper & lower limb X-rays, Magnetic Resonance imaging of Brain, Nerve conduction studies of Bilateral upper & lower limbs, Fundus examination, Cerebrospinal fluid examination were normal. The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was normal. His capsule endoscopy reconfirmed apthae in recto sigmoid area but rest all small bowel and large bowel were unremarkable. In view of diagnosis of Whipple’s disease, patient was started on 2 mg/day IV ceftriaxone therapy for two weeks which he tolerated well without any side effects. His stay in indoor ward remained uneventful and has been discharged under heamodynamically stable condition on twice daily trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole (160 mg TMP-800 SMX). He is asymptomatic and regularly coming for follow up.

Discussion

Our case report is of a eighteen year old young male, admitted with probable diagnosis of acute appendicitis & later on suspected to be having tubercular abdomen but on investigations was diagnosed with Whipple’s disease. The early diagnosis leading to urgent and proper treatment based on scientific rationale proves to be game changer in this rare and treatable disease (Figures 1-3). Whipple’s disease is usually seen in middle-aged males, involved in land & dairy farming and presents with prodromal findings of fever, fatigue, and joint disorders [4]. The Classical Whipple’s disease is characterized by a tetrad of symptoms: arthralgia, weight loss, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. In classical Whipple’s disease, prodromal symptoms are generally followed by abdominal pain, nausea, chronic/intermittent diarrhea, and severe weight loss due to malabsorption. Gastrointestinal findings are the most common clinical manifestations in about 90–95% of the patients [5].

Chronic intermittent polyarthritis is seen in 65–70% of the patients, which is usually migratory and nonerosive, affecting large joints. The gender, rural background and occupational exposure was consistent with the disease pattern, but age was younger than reported in literature. There were no prodromal symptoms like anorexia, weakness, headache, and joints discomfort. In our case, the main symptom was crampy pain abdomen and acute diarrhea but there were no features of malabsorption, weight loss or systemic involvement except for gastrointestinal tract as evidenced by histopathological diagnosis of colonoscopic biopsy and positive stool for occult blood test. In Whipple’s disease, multisystem involvement can be seen like Central nervous system involvement can lead to dementia, seizures, ataxia , psychiatric disturbances, oculomasticatory or oculo-facial-skeletal myorhythmia [6]. The other manifestations include rashes, papules, culturenegative endocarditis, uveitis ,retinitis, optic neuritis, pulmonary involvement, lymph node involvement, or spondylodiscitis [7].

In our case there was no systemic involvement. The definitive diagnosis of Whipple’s disease is made on basis of infiltration of foamy macrophages containing dense PAS-positive granules in the lamina propria on histopathological examination of the biopsy material. In our case, surprisingly small bowel was spared as evidenced by capsule endoscopy and only selective involvement of recto sigmoid area of large bowel was seen. The PCR analysis for T.Whippeli could not be done due to unavailability of the same at our institute. Other infectious causes, inflammatory bowel diseases, connective tissue diseases, hyperthyroidism, and celiac disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis of Whipple’s disease. Moreover, other rare causes of PAS positive macrophage infiltration in the small intestine should also be assessed with additional tests for histoplasmosis, Rhodococcus, and HIV-infected mycobacterium disease [8].

In our patient, duodenum biopsy was also obtained for the differential diagnoses of other diseases, but it was normal. The treatment recommended for Whipple’s disease include penicillin (2 MU IV every 4 h) or ceftriaxone (2 g IV single dose daily) for 2–4 weeks followed by trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole (160 mg TMP- 800 SMX twice daily) for at least 12 months. We used ceftriaxone 2 gm IV daily once for two weeks and then discharged patient on trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole (160 mg TMP-800 SMX twice daily). The response is monitored by clinical examination as chances of relapse are always there due to inadequate eradication of microorganisms [9].

Conclusion

Whipple’s disease is a rare disease and often diagnosis is delayed. It should always be kept as differential diagnosis in patients with abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, seronegative arthritis, culture negative endocarditis, pyrexia of unknown origin, chronic serositis, myoclonus, ophthalmoplegia. There can be atypical presentation also, like in our case, as evidenced by early age of involvement, short history, lack of prodromal symptoms, sparing of small bowel & selective involvement of large bowel and no systemic involvement. Thus, clinicians should have high index of suspicion for diagnosing this rare disease which can have both typical as well as atypical presentation.

Acknowledgement

Department of Pathology, PGIMS, Rohtak and Department of Surgery, PGIMS, Rohtak.

References

- Biagi F, Balduzzi D, Delvino P, Schiepatti A, Klersy C, et al. (2015) Prevalence of Whipple’s disease in north-western Italy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34(7): 1347-1348.

- Ojeda E, Cosme A, Lapaza J, Torrado J, Arruabarrena I, et al. (2010) Whipple’s disease in Spain: a clinical review of 91 patients diagnosed between 1947 and 2001. Rev EspEnferm Dig 102(2): 108-123.

- Marth T (2016) Whipple’s disease. Acta Clin Belg 71(6): 373-378.

- Obst W, von Arnim U, Malfertheiner P (2014) Whipple’s Disease. Viszeralmedizin 30(3): 167-172.

- Marth T (2015) Systematic review: whipple’s disease (Tropherymawhipplei infection) and its unmasking by tumour necrosis factor inhibitors. Aliment PharmacolTher. 41(8): 709-724.

- Anderson M (2000) Neurology of Whipple’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 68(1): 2-5.

- AlHamoudi W, Habbab F, Nudo C, Nahal A, Flegel K (2007) Eosinophilic vasculitis: a rare presentation of Whipple’s disease. Can J Gastroenterol 21(3): 189-191.

- Durand DV, Lecomte C, Cathébras P, Rousset H, Godeau P (1997) Whipple disease. Clinical review of 52 cases. The SNFMI Research Group on Whipple Disease. SociétéNationaleFrançaise de Médecine Interne [Baltimore]. Medicine (Baltimore) 76(3): 170-184.

- Lagier JC, Fenollar F, Lepidi H, Giorgi R, Million M, et al. (2014) Treatment of classic Whipple’s disease: from in vitro results to clinical outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother69(1): 219-227.