Safety and Efficacy of Modified BRTO-Assisted Endoscopic Histoacryl Injection for the Treatment of Isolated Gastric Varices with Gastro-Renal Shunt

Yanling Wang, Huijun Zhang, Jun Han, Xiaobao Qi, Tingting Liu and Wenhui Zhang*

Department of Liver Cirrhosis Diagnosis and Treatment Center, Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital of China, China

Submission:November 05, 2020;Published:November 12, 2020

*Corresponding author:Wen-hui Zhang, Endoscopy Center Director Liver Cirrhosis Diagnosis and Treatment Center, Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Feng-tai District, Beijing, China

How to cite this article:Yanling W, Huijun Z, Jun H, Xiaobao Q, Tingting L, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Modified BRTO-Assisted Endoscopic Histoacryl Injection for the Treatment of Isolated Gastric Varices with Gastro-Renal Shunt. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol, 2020;16(2): 555933. DOI: 10.19080/ARGH.2020.16.555933.

Abstract

Background and Aims:Ectopic embolization is the most serious complication of gastric variceal Histoacryl injection for the treatment of Isolated Gastric Varices (IGV) with Gastro-Renal Shunt (GRS). To evaluate the safety and efficacy of modified balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration-assisted Endoscopic Histoacryl Injection (E-BRTO) for the treatment of IGV with GRS.

Methods:Patients that had IGV with significant GRS, treated with E-BRTO, were included in this study. The GRS was temporarily occluded with an occlusion balloon and the IGV was treated by Endoscopic Histoacryl Injection using the “sandwich technique”. Intra- and postoperative complications as well as the IGV eradication, re-bleeding, and recurrence rates were recorded and analyzed.

Results:22 patients were included in this study. The mean volume of Histoacryl used was 16.57±11.76mL. No deaths or serious complications were observed, including ectopic embolism and the worsening of hepatic and renal functions. IGV were eradicated in 22 cases (100%). Abdominal pain and fever was observed in one patient (4.55%), recurrence and re-bleeding of IGV in one patient (4.55%), who was recovery by another Histoacryl injection.

Conclusion:E-BRTO is technically feasible, safe, and effective for the treatment of IGV associated with GRS in cirrhotic patients and worthy of clinical application.

Keywords: BRTO; Ectopic embolism; Gastro-renal shunt; Histoacryl; Isolated gastric varices

Abbreviations: BRTO: Balloon-Occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration; CTV: Computed Tomography and Venography; E-BRTO: BRTO-Assisted Endoscopic Histoacryl Injection; EC: Ectopic Embolization; EV: Esophageal Varices; EVS: Esophageal Variceal Sclerotherapy; HVPG: Hepatic Vein Pressure Gradient; IGV: Isolated Gastric Varices; GRS: Gastro-Renal Shunt; PHG: Portal Hypertensive Gastropath; TIPS: Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt

Introduction

Esophagogastric varices are some of the most frequent complications of liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. The incidence rate of Isolated Gastric Varices (IGV) is lower than Esophageal Varices (EV). The prevalence of IGV in patients with portal hypertension is about 10%~50%. The frequency of bleeding is up to 10-36% and the re-bleeding rate ranges from 34% to 89%, but the mortality risk is as high as 25~55% [1,2]. The current therapeutic options for IGV include medications, endoscopic therapy, surgery, and radiological interventions such as Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) and balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) [3]. TIPS is useful for the treatment of IGV with large-diameter gastro-renal shunts (GRS). Some studies have shown that the long-term re-bleeding rate of IGV after TIPS is lower than that of tissue adhesive injection, but the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy is significantly higher [4].

BRTO is used for IGV in patients that have spontaneous shunt (gastro-renal or spleno-renal shunt) [5]. BRTO is one of the recommended treatments for gastric variceal rebleeding [6]. However, there are some drawbacks to this procedure such as sclerosant-associated intravascular hemolysis, treatment failure due to balloon rupture, and a potential increase in EV [7]. Moreover, in BRTO, the indwelling occlusion balloon is kept in place postprocedure for several hours to ensure complete resolution of the IGV and the patients need to be closely monitored [8]. Keeping the balloon in situ increases the chances of bleeding and infection and causes inconvenience to the patients [9]. EV and ascites often become aggravated after the procedure due to the increase in portal venous pressure after shunt occlusion [3,10]. Consequently, isolated embolization of IGVs with GRS is greatly limited. At present, endoscopic Histoacryl (cyanoacrylate) injection is the preferred method for controlling acute gastric variceal bleeding, and the hemostasis rate is as high as 90% [1,11]. Endoscopic Histoacryl injection therapy is also recommended by the Baveno VI Consensus Seminar for hemostasis and the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding [12].

IGV drain into the left renal vein via GRS in 80-85% of cases [13]. Ectopic Embolization (EC) is the most serious complication of gastric variceal Histoacryl injection. GRS increases the risk of EC including pulmonary embolism, splenic infarction, cerebral infarction, and myocardial infarction [14,16]. Therefore, treatment of IGV associated with GRS is challenging. In order to prevent EC, we performed a modified BRTO-assisted Endoscopic Histoacryl Injection (E-BRTO). During this procedure, BRTO is performed to achieve transient occlusion of the GRS during endoscopic Histoacryl injection. In this manner, we could reduce the side effects and could more effectively tackle IGV with GRS than with either treatment alone. The transient occlusion of GRS could effectively prevent EC without increasing the portal venous pressure. In this study, we analyzed the technical safety, clinical safety, and effectiveness of this promising approach.

Materials and Methods

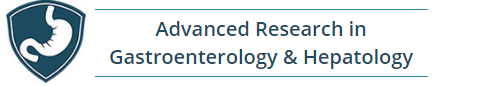

In this retrospective study, the data for patients that had IGV with or without EV and GRS and underwent E-BRTO between January 2016 and July 2019 at our center was collected. All patients provided informed consent prior to the treatment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fifth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital in Beijing. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed to assess the severity of IGV. Contrastenhanced Computed Tomography and Venography (CTV) of the portal venous system was performed to visualize the feeding and draining veins of the IGV (Figure 1A).

Inclusion criteria

a) Age between 20 and 75 years.

b) Presence of liver cirrhosis diagnosed by clinical examination or radiological imaging.

c) History of gastrointestinal bleeding on or before admission treated pharmacologically.

d) 4) IGV diagnosed by endoscopy with no other potential source of bleeding.

e) A large GRS (6 mm < GRS < 10 mm) associated with IGV detected on preoperative imaging.

Exclusion criteria

a) Presence of hepatocellular carcinoma or other malignancies.

b) Past history of TIPS, surgical or endoscopic therapy for esophagogastric variceal bleeding.

c) Presence of large GRS too wide to be occluded by the largest available occlusion catheter.

d) Presence of hepatic encephalopathy, and

e) Uncontrolled infection. Equipment

The Olympus GIFQ260J endoscope (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan), Histoacryl (N-butyl-cyanoacrylate) (Compont, Beijing, China), DSA angiography machine (SIEMENS, AXIOM Artis U), balloon catheter (Termao, Japan), and a 23-G disposable injection needle (MTW, Germany) were used.

Technique

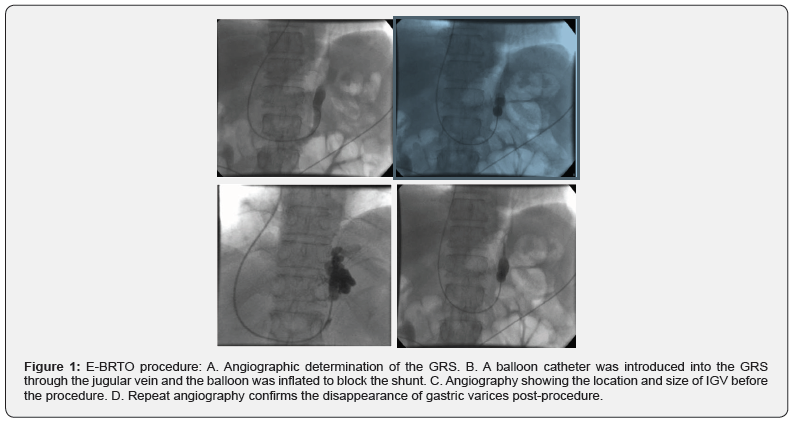

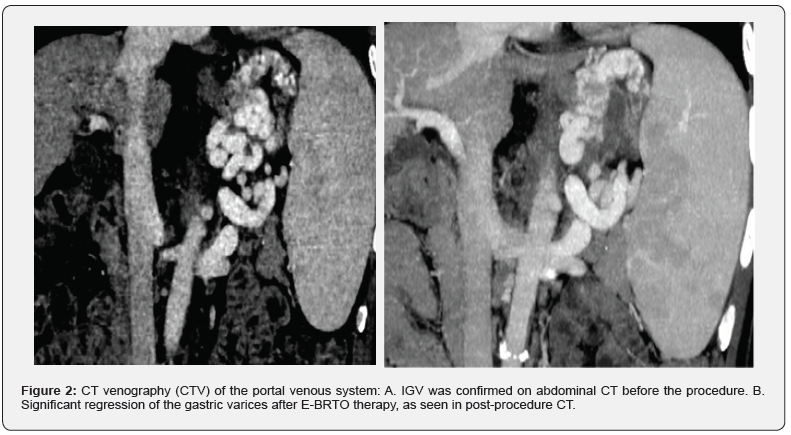

A 5.5F balloon occlusive catheter was introduced into the hepatic vein through the right internal jugular vein or the right femoral vein. The wedge pressure of the hepatic vein was measured after balloon occlusion of the hepatic vein. The free pressure of the hepatic vein and the inferior vena cava pressure were measured after removal of the occlusion. Finally, the Hepatic Vein Pressure Gradient (HVPG) was calculated. Angiography was performed to visualize the prominent GRS and IGV (Figure 1B). According to the diameter of GRS, a balloon catheter with appropriate size was selected to block the GRS. The balloon occlusive catheter was introduced into the shunt and inflated to occlude the GRS (Figure 1C). Repeat angiography was performed to evaluate the position and size of the IGV (Figure 1D). The patient was placed in a left lateral position and the vital parameters of the patient (including heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and blood pressure) and electrocardiogram were continuously monitored preoperatively. Endoscopic examination was conducted to confirm the presence of GV and the volume of the varices (Figure 2A). Histoacryl was injected into the GV at multiple points. Each injection was performed with the “sandwich technique” i.e. 1.5mL Histoacryl was sandwiched between two doses of 2mL 50% glucose solution depending on the volume of the needle (Figure 2B). After each injection location, a satisfactory result was defined as hardening of the varices on gentle probing of the varices using a needle catheter. At the end of the procedure, before removing the balloon catheter, a repeat angiogram was performed to confirm the resolution of the IGV (Figure 1D). The therapy was defined as successful if the blood supply of the IGV was completely obliterated. The balloon occlusive catheter was then deflated and removed.

Treatment and follow-up

Antibiotics were routinely administered for 5-7 days after the procedure [17]. Post-treatment repeat radiological imaging was conducted to observe the varices if any remained (Figure 3A). Re-examination by endoscopy was also performed to confirm the resolution of the IGV (Figure 3B, 3C,3D), indicating successful treatment. A detailed operative note for each patient was carefully recorded. Repeat endoscopic examinations and follow-ups were performed after the E-BRTO procedure to identify complications, residual varices, recurrence, re-bleeding, aggravation of EV, and survival rates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 23.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD, while categorical variables were presented as the percentage ratio. P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

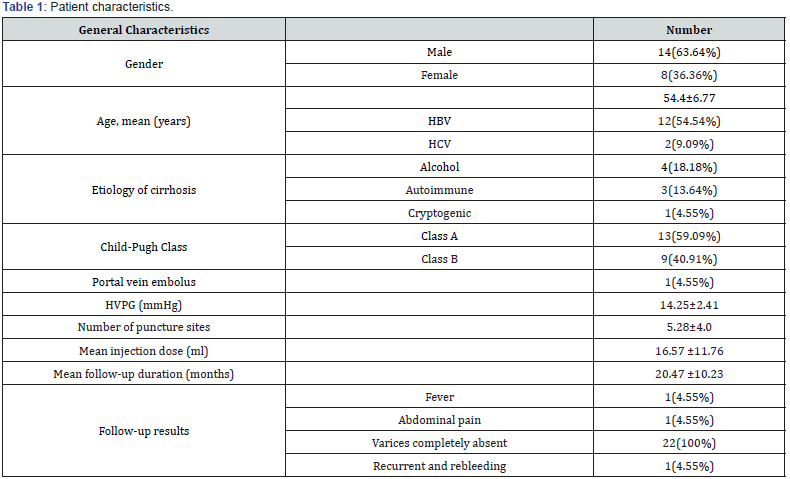

Twenty-tow patients were included in this study, comprising 14 men and 8 women. The etiologies of cirrhosis were hepatitis B virus infection in 12 cases (54.54%), hepatitis C virus infection in two cases (9.09%), alcohol in four cases (18.18%), autoimmunerelated in three cases (13.64%), and cryptogenic in one case (4.55%). All of the patients had IGV. All patients completed the E-BRTO procedure with a technical success rate of 100% (Table 1). The Child-Pugh scores for all of the 22 patients did not change after the treatment.

The mean HVPG value was 14.25±2.41mmHg. The mean volume of Histoacryl used was 16.57±11.76mL, and the mean number of puncture sites was 5.28±4.0. Postoperative complications included fever (1 of 22, 4.55%) and abdominal pain (1 of 22, 4.55%). All complications were transient and resolved within 24h with symptomatic therapy. The survival rate was 100% during the mean follow-up period of 20.47±10.23 months. The varices completely disappeared in 22 cases (100%). Recurrence and re-bleeding occurred in one patient, who was treated successfully by another endoscopic Histoacryl injection experienced 22 months after the procedure. The re-bleeding rate observed at 22 months was 4.55%. No new EV or the aggravation of pre-existing EVs or portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) was observed. No complications such as ectopic embolism and deterioration of liver and kidney function were found.

Discussion

In contrast to EV, the anatomy and hemodynamic indexes of IGV are more complex.3 Bleeding from IGV is usually large in volume and the mortality rate is high.1 Although BRTO has been shown to have good clinical outcomes in IGV treatment, the optimal treatment for IGV has not yet been established [18]. Endoscopic Histoacryl injection has recently become the first-line therapy for IGV [19]. A potentially fatal complication of Histoacryl injection is the development of ectopic embolism due to migration of the Histoacryl into the systemic circulation [20]. A multicenter study showed that the incidence of asymptomatic ectopic embolism after cyanoacrylate injection therapy is high [21]. In particular, the risk of ectopic embolism in IGV accompanied by GRS is significantly high [14]. Therefore, the existence of GRS is an important factor in the selection of treatment methods for IGV. Kanagawa [22]. first reported the use of BRTO in 1991 [22].22 Many years of clinical practice have demonstrated that BRTO is safe and effective for the treatment of IGV [23]. Modified BRTO can achieve better therapeutic effects than traditional BRTO and TIPS [24]. Hamamoto [25]. successfully treated a IGV patient with a combined technique, in which the sclerosant was endoscopically injected into the IGV while the GRS was temporarily occluded by BRTO. Studies have found that titanium clips can be safely used along with tissue adhesive injection in the treatment of IGV complicated by GRS [26]. Since Levy et al. first used coils to treat ectopic varices in 2008 [27]. This technology has been increasingly applied in clinical practice. Clinicians have used coils in combination with Histoacryl embolization to treat IGV, and the results have been encouraging [28], Based on previous studies, we used the modified BRTO technique in combination with Histoacryl injection for the treatment of IGV associated with GRS. Preoperative Computed Tomography (CT) angiography can be used to identify GRS in order to determine patients eligible for BRTO. Preoperative HVPG can help in determining the appropriate treatment modality for patients with IGV [29]. HVPG≥20mmHg indicates that the failure rate and risk of mortality with endoscopic hemostatic treatment will be high in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal hemorrhage [30]. The failure and 1-year mortality rates for patients treated using conventional drugs combined with endoscopic therapy were higher among patients with HVPG≥20mmHg than those with HVPG < 20mmHg [31]. The mean value of HVPG was 15mmHg in this study, which may be responsible for the positive outcomes of the current study. There was no significant change in HVPG before and after treatment. To prevent ectopic embolism, the shunt was temporarily occluded by a balloon. During this procedure, Histoacryl was injected into all the IGV to achieve permanent obliteration. Studies have found that despite the occlusion of the drainage vein, migration of cyanoacrylate into the pulmonary artery can still occur. The study suggested that the incidence of such complications was probably due to delayed coagulation with lipiodol [32]. In ectopic lipiodol embolism cases, cerebral embolism and pulmonary embolism have been reported [33]. Compared with the traditional “sandwich technique”, a lipiodol-free dilution with hypertonic glucose can increase operational compliance [34]. In this study, the “sandwich technique” i.e. Histoacryl sandwiched by 50% glucose solution was adopted. Post-injection angiography evaluation as done in this study can improve the efficacy and decrease re-bleeding incidence [35]. Moreover, 4.55% of the study patients had coexistent portal venous thrombosis, which makes alternative treatment such as the TIPS procedure challenging. E-BRTO is a safe alternative for TIPS in such cases. In this study, the technical success rate was 100%. Complete resolution of IGV after E-BRTO was observed in 100% of cases. The IGV recurrence and re-bleeding rate was 4.55% (1/22), and the survival rate was 100%. None of the patients developed distant emboli. Based on these findings, we suggest that E-BRTO is a viable treatment option for IGV with concurrent GRS. The main reasons for the high success rate in this study were as follows: 1) HVPG was measured via the hepatic vein in the beginning to develop the treatment plan, 2) GRS was temporarily embolized, which prevented an increase the portal vein pressure and the aggravation of PHG. 3) The “sandwich technique” without lipiodol reduced the risk of ectopic lipiodol embolism. This study is limited by its retrospective nature, small sample size, and single center experience. Future prospective multicenter studies are necessary to confirm our results. In summary, our preliminary study showed that E-BRTO is a feasible, safe, and effective alternative procedure to treat IGV with concurrent GRS.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Bo Jin and Dr. Chunsheng Chi at Liver Cirrhosis Diagnosis and Treatment Center for their support and assistance with the BRTO intervention in this article.

References

- Crisan D, Tantau M, Tantau A (2014) Endoscopic management of bleeding gastric varices-an updated overview. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 16(10): 143.

- De Franchis R, Baveno V Faculty (2010) Revising consensus in portal hyper-tension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in port al hypertension. J Hepatol 53(4): 762-768.

- Chang CJ, Hou MC, Liao WC, Ping Hsien C, Han Chieh L, et al. (2013) Management of acute gastric varices bleeding. J Chin Med Assoc 76(10): 539-546.

- Li Jing, Jiang Yong, Zhang Xu (2019) Meta-analysis of the effect of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and endoscopic tissue glue injection on gastric variceal hemorrhage. Journal of Clinical Hepatobiliary Diseases 35 (2): 349-353.

- Park JK, Saab S, Kee ST,Ronald WB, Hyun JK, et al. (2015) Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) for treatment of gastric varices: review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 60(6): 1543-1553.

- Garcia-Tsao G,Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J (2017) Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 65(1): 310-335.

- Gwon DI, Ko GY, Yoon HK, Kyu BS, Jin Hyoung K, et al. (2013) Gastric varices and hepatic encephalopathy: Treatment with vascular plug and gelatin sponge-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration-Aprimary report. Radiology 268(1): 281-287.

- Imai Y, Nakazawa M, Ando S, Sugawara K, Mochida S (2016) Long-term outcome of 154 patients receiving balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric fundal varices. J Gastroenterology Hepatology 31(11): 1844-1850.

- Luo X, Ma H, Yu J, Zhao Y, Wang X, et al. (2018) Efficacy and safety of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices with lauromacrogol foam sclerotherapy: initial experience. Abdominal Radiology 43(7): 1820-1824.

- Imai YM, Nakazawa M, Ando S, Kayoko S, Satoshi M, et al. (2016) Long-term outcome of 154 patients receiving balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric fundal varices. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 31(11): 1844-1850.

- EIOmar EM (2006) Mechanisms of increased acid secretion after eradication of helicobacter pylofi Gut 55(2):144-145.

- De Franchis R (2015) Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 63(3): 743-752.

- GabaRC, CouturePM, LakhooJ (2015)Gastroesophageal variceal filling and drainage pathways: an angiographic description of afferent and efferent venous anatomic patterns. J Clin Imaging Sci 5(5): 1-6.

- Michael PG, Antoniades G, Staicu A, Shahid S (2018) Pulmonary Glue Embolism: An unusual complication following endoscopic sclerotherapy for gastric varices. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J18(2): e231-e235.

- Upadhyay AP, Ananthasivan R, Radhakrishnan S, G Zubaidi (2005)Cortical blindness and acute myocardial infarction following injection of bleeding gastric varices with cyanoacrylate glue. Endoscopy 37(10): 1034.

- Joo HS, Jang JY, Eun SH, Sang KK, Jung IS, et al. (2007) Long-term results of endoscopic histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) injection for treatment of gastric varices–a 10-year experience. The Korean Journal of Gastroenterology49(5): 320-326.

- Lee YY,Tee HP,Mahadeva S (2014) Role of prophylactic antibiotics in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol20(7):1790-1796.

- GarciaPagán JC, Barrufet M, Cardenas A, Escorsell A (2014) Management of gastric varices. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 12(6): 919-928.

- Jun CH, Kim KR, Yoon JH, Han RK, Won SC, et al. (2014) Clinical outcomes of gastric variceal obliteration using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in patients with acute gastric variceal hemorrhage. Korean J Intern Med 29(4): 437-444.

- Naga M, Foda A (1997) An unusual complication of histoacryl injection. Endoscopy 29(2): 140.

- RomeroCastro R, Ellrichmann M, OrtizMoyano C,Subtil Inigo JC, JunqueraFlorez F, et al. (2013) EUS-guided coil versus cyanoacrylate therapy for the treatment of gastric varices: a multicenter study (with videos). GastrointestEndosc 78(5): 711-721.

- Kanagawa H, Mima S, Kouyama H,Tanabe T, Itou Y, et al. (1991) A successfully treated case of fundic varices by retrograde transvenous obliteration with balloon. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 88(7): 1459-1462.

- Qiong Wu, Hua Jiang, EnqiangLinghu, Lanjing Z, Weifeng W, et al. (2016) BRTO assisted endoscopic Histoacryl injection in treating gastric varices with gastro-renal shunt. Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies 25(6): 337-344.

- Peng Lunhua, Wang Yunbing, Guo Can (2016)Meta Analysis of Retrograde Transvenous Occlusion by Balloon Blocking and Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt for Treatment of Portal Hypertension and Gastric Fundus Varicosis Bleeding. Journal of Interventional Radiology 25(10): 843-848.

- Matsumoto A, Hamamoto N, Nomura T,Ichiro H,Hiroshi M, et al. (1999)Treatment of gastric fundal varices by balloon endoscopic sclerotherapy. GastrointestEndosc49(1): 115-118.

- Zhang M, Li P, Mou H,Yongjun Shi, Biguang Tuo, et al.(2019) Clip-assisted endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection for gastric varices with a gastro-renal shunt: a multicenter study. Endoscopy 51(10): 936-940.

- Levy MJ, Wong Kee Song LM, Kendrick ML, Misra S, Gostout CJ (2008)EUS-guided coil embolization for refractory ectopic variceal bleeding (with videos). GastrointestEndosc 67(3): 572-574.

- Maíra Ribeiro De AL, Dalton MC,DiogoTurianiHourneaux DEM, Igor BR, Eduardo I, et al. (2019)Safety and efficacy of EUS-guided coil plus cyanoacrylate versus conventional cyanoacrylate technique in the treatment of gastric varices: a randomized controlled trial. Arq Gastroenterol 56(1): 99-105.

- Procaccini NJ, AlOsaimi AM, Northup P, Argo C, Caldwell SH (2009) Endoscopic cyanoacrylate versus transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for gastric variceal bleeding: a single-center U.S. analysis. GastrointestEndosc 70(5): 881-887.

- Chinese Portal Hypertension Diagnosis and Monitoring Study Group (CHESS) (2018)Consensus on clinical application of hepatic venous pressure gradient in China. TurkiyeKlinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences 38(4): 382-396.

- Monescillo A, MartínezLagares F, RuizdelArbol L, (2004) Influence of portal hypertension and its early decompression by TIPS placement on the outcome of variceal bleeding. Hepatology 40(4): 793-801.

- Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Li CZ, Lin W, Yeo AE, et al. (2010)Low incidence of complications from endoscopic gastric variceal obturation with butylcyanoacrylate. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 8(9): 760-766.

- Wu L, Yang YF, Liang J,Shu Qun S, Nai Jian G, et al. (2010)Cerebral lipiodol embolism following transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 16(1): 398-402.

- Kumar A, Singh S, Madan K, Garg PK, Acharya SK (2010)Undiluted N-butyl cyanoacrylate is safe and effective for gastric variceal bleeding. GastrointestEndosc 72(4): 721-727.

- Rice JP, Lubner M, Taylor A, Bret JS, Adnan S, et al. (2011)CT portography with gastric variceal volume measurements in the evaluation of endoscopic therapeutic efficacy of tissue adhesive injection into gastric varices: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci 56(8): 2466-2472.