Hepatitis B Elimination - Preventing Vertical Transmission is must

Vani Malhotra*, Parveen Malhotra, Paramjeet Singh Gill, Smiti Nanda, Vandana Rani and Meenakshi Chauhan

Department of Gynecology & Obstetrics, Medical Gastroenterology and Microbiology, India

Submission: April 15, 2019; Published: June 12, 2019

*Corresponding author:Vani Malhotra, Department of Gynecology & Obstetrics, Medical Gastroenterology and Microbiology, 128/19, Civil Hospital Road, Rohtak, Haryana, 124001, India

How to cite this article: Vani M, Parveen M, Paramjeet Singh G, Smiti N, Vandana R. Hepatitis B Elimination - Preventing Vertical Transmission is must. 002 Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol. 2019; 13(2): 555857. DOI: 10.19080/ARGH.2019.13.555857.

Abstract

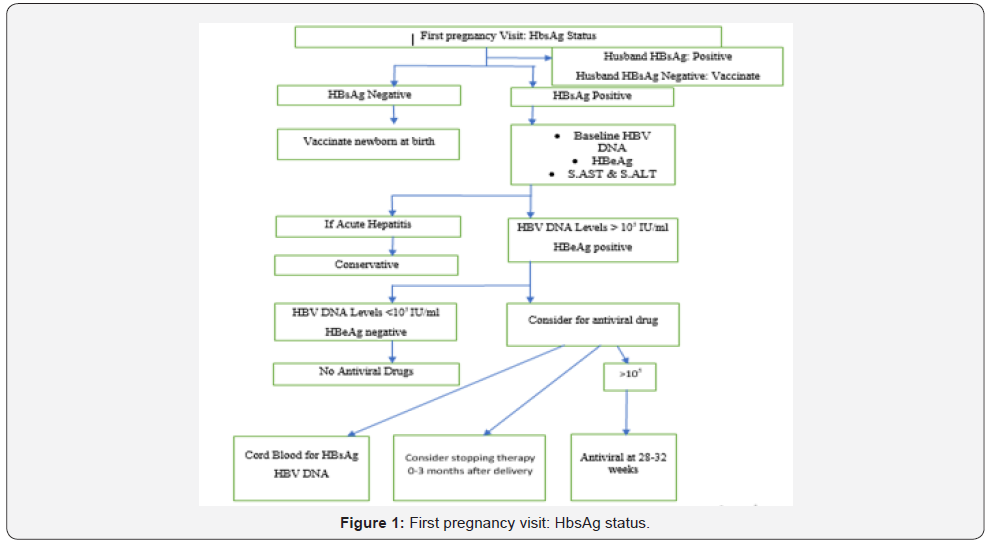

Introduction: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global problem with nearly 350 million chronic carriers, who are at risk of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Over 50% of these carriers are believed to have acquired their infection vertically from their mothers, i.e. through mother to child transmission (MTCT). Vertically acquired HBV infections frequently (>90%) become chronic. Review of literature: Chronic HBV infection during pregnancy is an important opportunity to interrupt perinatal transmission of HBV. The HbsAg-positive pregnant woman should be counseled to inform their obstetricians so that immunoprophylaxis can be administered to the newborn immediately after delivery. Recommendations: All the antenatal women should be tested for HbsAg and who are found positive should be encouraged to have institutional delivery and immunization of newborn during its first hours of life. Women who are having acute hepatitis are to be managed conservatively but chronic carriers should be treated with tablet Tenofovir 300 mg once a day according to HBV DNA levels & HbeAg status starting from 28-32 weeks of gestation. HBV DNA levels more than 105 IU/ml and positive for HbsAg status are indication for starting antiviral drugs. Conclusion: In India which is having intermediate prevalence of hepatitis B (2% - 8%), every pregnant woman should be screened for HbsAg and if found positive should be followed as per scientific protocol. The institutional based delivery for all these women will help in achieving goal of hepatitis B vaccination, including zero dose vaccination and hepatitis B immunoglobulin, thus helping in vertical transmission to newborn.

Keywords: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors; AIH-PBC overlap; Geftinib; Nitrofurantoin; Minocycline; Bile duct injury; Anti-neoplastic medications; Idiosyncratic; Liver failure; Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation

Abbrevations: TKIs: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors; EGFR: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; DI-AIH: Drug Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis; DILI: Drug Induced Liver Injury; AST: Aspartate Transaminase; ALT: Alanine Transaminase; GGT: Gamma Glutamyl Transpeptidase; ANA: Anti-Nuclear Antibody; AMA: Anti-Mitochondrial Antibody; ASMA: Anti-Smooth Muscle Antibody

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global problem with nearly 350 million chronic carriers, who are at risk of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. Over 50% of these carriers are believed to have acquired their infection vertically from their mothers, i.e. through mother - to - child transmission (MTCT). Vertically - acquired HBV infections frequently (>90%) become chronic [2].

The proportion of babies that became HBV chronic carriers is about 10% to 30% for mothers who are HBsAg positive but HBeAg negative. However, the incidence of perinatal infections is higher, i.e. 70% to 90%, when the mother is also HBeAg positive [3]. There are three possible routes of transmission of HBV from infected mothers to infants: transplacental transmission of HBV in utero, natal transmission during delivery or post-natal transmission during care of infant or through breast milk [4]. Though several studies on epidemiology of viral hepatitis in pregnancy are available, there is paucity of data on maternal to child transmission (MTCT) of HBV during pregnancy.

Review of Literature

Chronic HBV infection during pregnancy is an important opportunity to interrupt perinatal transmission of HBV.HBV infection does not appear to influence fertility or conception per se, beyond the effects of cirrhosis or liver failure5.If cirrhosis has set in, then pregnancy may be a rare event. Women with advancedchronic liver disease, regardless of cause, have decreased fertility as a result of frequent occurrence of anovulatory cycles and amenorrhoea6. The rate of spontaneous abortion is also significantly higher in women with cirrhosis, reaching 30% to 40% vs. 15% to 20% in the general population [5]. Cirrhotic women are at risk of developing significant perinatal complications and poor pregnancy outcomes, including intrauterine growth restriction, intrauterine infection, premature delivery, and intrauterine foetal demise. In recent years, the availability of reproductive technologies and advanced support measures has allowed a larger proportion of women with cirrhosis to carry pregnancies successfully to term [6].

HBV Infection during pregnancy does not appear to increase maternal or fetal mortality and morbidity. A large study that compared 824 HBeAg positive mothers to 6,281 HBsAg negative control mothers found no difference in rates of preterm delivery, birth weight, neonatal jaundice, congenital anomalies, or perinatal mortality [7]. However, a recent study showed that HBsAg carrier mothers had an increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus, antepartum haemorrhage, and threatened preterm labor [8].

The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) recommends that all pregnant women be screened for HBsAg during the first trimester, even if previously vaccinated or tested [9]. Screening allows for identification of infants requiring immunoprophylaxis with HBV vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG), anti-viral treatment of pregnant carriers if indicated, and counselling of sexual and household contacts [2]. The HbsAg-positive pregnant woman should be counseled to inform their obstetricians so that immunoprophylaxis can be administered to the newborn immediately after delivery [9]. Women who test negative for HBsAg and are at risk of acquiring HBV infection should be immunized during pregnancy. The hepatitis B vaccine is considered safe during pregnancy with no adverse reactions reported.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and AASLD guidelines suggest that HBsAg-positive mothers be referred for further medical evaluation so that those with liver disease can be identified and monitored frequently by a team of specialists. This should not be deferred to the postpartum period [9].

The medical dictionary defines the phrase “vertical transmission” of an infection as the transmission of pathogen from mother to child during pregnancy or childbirth, or by breastfeeding. Vertical transmission of HBV infection is the main reason for the continued endemic infection of HBV in Asia. Approximately 90 % of children who get HBV infection vertically from their mothers fail to clear the infection and develop chronic infection.

The risk of vertical transmission of HBV predominantly depends on the maternal HBV viral load and HBeAg status.

Vertical transmission of HBV is defined as positivity at 6-12 months of life of the hepatitis B surface antigen or of HBV DNA in an infant born to an infected mother. The presence of both HBsAg and HBV DNA at birth are transitory events and do not imply transmission of the infection [10]. Similarly, the presence of antibodies against hepatitis B e antigen or antibodies against Hepatitis b core antigen at birth or up to two years of age is simply due to crossing the placenta from mother to the fetus and therefore is unrelated to infection [11].

Modes of vertical transmission

Vertical transmission can occur in-utero, during delivery, or after delivery.

In-utero transmission: HBV can cross the placental barrier and reach the fetus; however, the impact of this mode is not clear. In a study from the United States, of 72 pregnancies, 13 (18 %) cord blood samples were positive for HBsAg [12]; however, HBV DNA was detected in only three (23 %) of these. In a Chinese study, only 3.7 %of babies tested HBsAg-positive at birth from in-utero infection [13]. Hence it is suggested that in-utero transmission may not be the predominant mode of transmission of HBV. In-utero or transplacental HBV infection cannot be blocked by HBV vaccine or HBIG given at birth and is an important reason for immunoprophylaxis failure. The mechanism of intrauterine transmission of Hepatitis B was studied by Zhang et al. [4] on 59 HBsAg-positive mothers. Both HBsAg and HBcAg were detected in the placenta from HBsAg-positive mothers. The concentration of two antigens decreased from mother’s side to fetal side but in four patients, the concentration was in reverse order. The authors concluded that although the predominant rout of transmission was transplacental, other routes of infection may exist.

The main risk factors for intrauterine HBV infection are maternal serum HBeAg positivity, high maternal viral load, and a history of threatened preterm labor or threatened abortion [6]. Zou et al. [14] studied a large cohort of 1043 mothers and found a correlation between maternal HBV DNA levels and immunoprophylaxis failure that indicated maternal pre-delivery HBV DNA level > 6 log copies/ ml are associated with reduced prophylaxis effectiveness. Bai et al. [15] corroborated this finding by showing that intrauterine transmission may be due to HBV crossing the placental barrier, according to positive HBV staining of placental tissue in mothers with high viral loads.

Transmission during delivery: This is widely believed to be the most frequent mode of MTCT. This is the reason why the neonatal administration of HBIG with vaccination is able to prevent newborn HBV infection in more than 85 % of cases. In one study, duration of labor showed a positive correlation with HBV antigenemia of the cord blood especially when the labor exceeded nine hours [16]. An elective cesarean section performed before the onset of labor and rupture of membranes may effectively interrupt such transmission and reduce the risk of vertical transmission as compared with vaginal delivery or cesarean section performed after the onset of labor or after rupture of membrane [17]. However, there is lack of agreement on this issue

There is conflicting evidence surrounding the effect of the mode of delivery on the risk of MTCT. A more recent meta-analysis revealed a 17.5% absolute risk reduction with cesarean section compared to immunoprophylaxis alone, suggesting a benefit of elective cesarean section compared to immunoprophylaxis alone, suggesting a benefit of elective cesarean section to reduce MTCT [18]. Lee et al. [19] investigated 1409 infants over a four-year period who had received appropriate immunoprophylaxis at birth and who had been born to HBsAg-positive mothers. They reported MTCT rates of 1.4% with elective cesarean section compared to 3.4% with vaginal delivery and 4.2% with urgent cesarean section. The society for Maternal Fetal Medicine states that cesarean section should not be performed for sole indication of reducing vertical transmission [20].

Postpartum transmission: In the immediate postpartum period, transmission results from close contact between mother and baby. Transmission of HBV by breastfeeding, either through ingestion of the virus or by contact with skin lesions on the mother’s breast, is another potential mechanism. Early studies reported HBsAg, HBeAg and HBV DNA detection in colostrum, with higher levels in mothers with high serum HBV DNA, suggesting that breast milk may be an important vehicle for transmission of HBV [21]. However, several studies have reported that breastfeeding carries no additional risk of transmission [22]. It has also beensuggested that breast milk may have antiviral properties since it contains immunoglobulins and other proteins such as lactoferrin.

In view of several benefits of breast feeding, WHO recommends breastfeeding for infants of HBsAg-positive mother seven in endemic areas where HBV vaccination may not be readily available [23].

High maternal HBV DNA titer is probably one of the most important risk factor for vertical transmission of HBV. HBV infection was found to occur in up to 10% of babies despite immunoprophylaxis and high maternal HBV DNA level was one of the most important risk factor for this. Traditionally HBeAg-positive mothers were considered to be at a higher risk of transmitting HBV infection to newborns than HBeAg-negative mothers, with the risks of chronic HBV infection by age of 6 months of 70 % to 90 %and 10 % to 40 %, respectively, in the absence of post-exposure immunoprophylaxis.

The mechanisms for high rate of infection in infants born to HBeAg-positive mothers remain unclear. Maternal HBeAg positivity is strongly correlated with high levels of maternal viremia.

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and AASLD guidelines both strongly recommend initiation of antiviral drugs in highly viremic patients at 28-32 weeks of gestation in order to reduce MTCT. Anti-viral therapy during pregnancy provides potent anti-viral suppression, is relatively safe and well tolerated, and reduces perinatal HBV transmission. Problems associated with such treatment include the risk of viral drug resistance in the mother depending on the antiviral agent used, contraindication to breast feeding, and the risk of hepatitis flares upon discontinuation23. Current recommendations by the AASLD cite HBV DNA levels> 2 X 105 IU/ml as an indication for initiation of therapy as risk of HBV transmission increases with level of viremia. The duration of treatment postpartum varies between 0-3 months depending on the indication for treatment initiation, HBsAg positivity and breastfeeding.

Tenofovir, a nucleotide analogue with activity against HV polymerase, is currently a preferred oral agent for HBV therapy. It has been used by pregnant women for HIV infection with no increase in congenital malformations. Preliminary data show no evidence of renal impairment, abnormal bone metabolism or impaired growth in children exposed to tenofovir in utero [24].

Most guidelines now recommend that infants born to HBsAg- positive women should receive both HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine within 12 h of birth, preferably in the delivery room. This should be followed by at least two more doses of hepatitis B vaccine within the first 6 months of life .Passive immunoprophylaxis with HBIG at birth followed by at least 3 doses of the vaccine provides 90 % to 95 %protection from perinatal infection, and is superior in reducing MTCT than HBIG or vaccine alone (RR 0.08, 95 % CI0.03–0.17) [25]. After completion of the vaccine series, HBsAg and anti-HBs should be tested by 9 months of age. HBsAg-negative infants with anti-HBs levels >10 mIU/mL are protected, and no further medical management is required. Those with anti-HBs levels <10 mIU/mL are not protected and should be revaccinated with another three-dose series followed by retesting 1 to 2 months after the final dose. With appropriate immunoprophylaxis, including HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine, breastfeeding of infants of chronic HBV carriers poses no additional risk of transmission of HBV18.In view of several benefits of breastfeeding, WHO recommends breastfeeding even for infants of HBsAg-positive mothers in endemic areas where HBV vaccination may not be readily available [21] (Figure 1).

Recommendations

a) All the antenatal women should be tested for HbsAg and who are found positive should be encouraged to have institutional delivery and immunization of newborn during its first hours of life. b) Detailed history and general, systemic and obstetric examination and evaluation of risk factors like tattooing, previous blood transfusions or operative procedures should be done for all HbsAg positive antenatal women. c) Complete hepatitis B profile including HBV DNA levels, HbeAg, HbeAg, IgM anti Hbc and liver function test are to be done which helps in differentiating acute hepatitis and chronic hepatitis. d) Women who are having acute hepatitis are to be managed conservatively but chronic carriers should be treated with tablet Tenofovir 300 mg once a day according to HBV DNA levels & HBeAg status starting from 28-32 weeks of gestation. HBV DNA levels more than 105 IU/ml and positive for HbsAg status are indication for starting antiviral drugs. e) The newborn should be given zero dose of HBV vaccine and HBIG within 12 hours of birth and next three doses of HBV at 6, 10 &14 weeks of life. All the newborns will be followed till 12 months of age with HbsAg and anti- HbsAg.

Conclusion

In India which is having intermediate prevalence of hepatitis B (2% - 8%), every pregnant women should be screened for HbsAg and if found positive should be followed as per scientific protocol. The institutional based delivery for all these women will help in achieving goal of hepatitis B vaccination, including zero dose vaccination and hepatitis B immunoglobulin, thus helping in vertical transmission to newborn.

References

- Lavanchy D (2005) Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol 34(Suppl 1): S1-3.

- Jonas MM (2009) Hepatitis B and pregnancy: an underestimated issue. Liver Int 299(Suppl 1): 133-139.

- Xu ZY, Liu CB, Francis DP, Purcell RH, Gun ZL, et al. (1985) Prevention of perinatal acquisition of Hepatitis B virus carriage using vaccine: preliminary report of a random double-blind placebo-controlled and comparative trail. Pediatrics 76(5): 713-718.

- Zhang SL, Yue YF, Bai GQ, Shi L, Jiang H (2004) Mechanism of intrauterine infection of hepatitis B virus. World J Gastroenterol 10(3): 437-438.

- Tan J, Surti B, Saab S (2008) Pregnancy and cirrhosis. Liver Transpl 14(8): 1081-1091.

- Degli Esposti S, Shah D (2011) Hepatitis B in pregnancy: challenges and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 40(2): 72-81.

- Wong S, Chang LY, Yu V, Ho L (1999) Hepatitis B carrier and perinatal outcome in singleton pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 16(9): 485-488.

- Tse KY, Ho LF, Lao T (2005) The impact of maternal HBsAg carrier status on pregnancy outcomes: a case-control study. J Hepatol 43(5): 771-775.

- Lok ASF, McMahon BJ (2009) Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology 50(3): 661-662.

- Yin P, Wu L, Zhang J, Zhou J, Zhang P, et al. (2013) Identification of risk factors associated with immunoprophylaxis failure to prevent the vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus. J Infect 66(5): 447-452.

- Wang JS, Chen H, Zhu QR (2005) Transformation of hepatitis B serologic markers in babies born to hepatitis B surface antigen positive mothers. World J Gastroenterol 11(23): 3582-3585.

- Pande C, Patra S, Kumar A, Sarin S (2010) Giving vaccine alone confers equal protection from chronic hepatitis B infection to neonates born of HBsAg positive mothers as compared to vaccine plus HBIG: A large randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 52(Suppl): 1008A.

- Xu DZ, Yan YP, Choi BCK, Xu JQ, Men K, et al. (2002) Risk factors and mechanism of transplacental transmission of hepatitis B virus: a case-control study. J Med Virol 67(1): 20-26.

- Zou H, Chen Y, Duan Z, Zhang H, Pan C (2012) Virologic factors associated with failure to passive-active immunoprophylaxis in infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers. J Viral Hepat 19(2): 19-25.

- Bai H, Zhang L, Ma L, Dou XG, Feng GH, Zhao GZ (2007) Relationship of hepatitis B virus infection of placental barrier and hepatitis B virus intra-uterine transmission mechanism. World J Gastroenterol 13(26): 3625-3630.

- Wong VC, Lee AK, Ip HM (1980) Transmission of hepatitis B antigens from symptom free carrier mothers to the fetus and the infant. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 87(11): 958-965.

- Yang J, Zeng X, Men Y, Zhao L (2008) Elective caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to child transmission of hepatitis B virus- a systematic review. Virol J 5: 100.

- Hu Y, Chen J, Wen J, Xu C, Zhang S, et al. (2013) Effect of elective caesarean section on the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13: 119.

- Lee SD, Lo KJ, Tsai YT, Wu JC, Wu TC, et al. (1988) Role of caesarean section in prevention of mother-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Lancet 2(615): 833-834.

- Dionne- Odom J, Tita AT, Silverman NS (2016) Hepatitis B in pregnancy screening, treatment and prevention of vertical transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214(1): 6-14.

- Yogeswaran K, Fung SK (2011) Chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy: unique challenges and oppurtunities. Korean J Hepatol 17(1): 1-8.

- Beasley RP, Stevens CE, Shiao IS, Meng HC (1975) Evidence against breast-feeding as a mechanism for vertical transmission of hepatitis B. lancet 2(7936): 740-741.

- Wiseman E, Fraser MA, Holden S, Glass A, Kidson BL, et al. (2009) Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus: an Australian experience. Med J Aust 190(9): 489-492.

- Giles M, Visuvanathan K, Sasadeusz J (2011) Antiviral therapy for hepatitis B infection during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Antivir Ther (Lond) 16(5): 621-628.

- Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C (2006) Effect of hepatitis B immunisation in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 332(7537): 328-336.