Epidemiology of Temporomandibular Disorder in the General Population: a Systematic Review

Joseph Ryan1, Rahena Akhter2*, Nur Hassan1, Glen Hilton1, James Wickham1 and Soichiro Ibaragi3

1Charles Sturt University, Australia

2University of Sydney, Australia

3Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Okayama University Hospital, Japan

Submission: February 01, 2019; Published: February 19, 2019

*Corresponding author: Dr. Rahena Akhter BDS, ADC (Melb.), PhD (Japan), Postdoc (Australia) Senior Lecturer, Cariology, Discipline of Tooth Conservation Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Sydney C24 Westmead Hospital, Level 1 WCOH, Westmead, New South Wales, Australia

How to cite this article: Joseph R, Rahena A, N Hassan, Glen H, James W, et al . Epidemiology of Temporomandibular Disorder in the General Population: a Systematic Review. Adv Dent & Oral Health. 2019; 10(3): 555787. DOI: 10.19080/ADOH.2019.10.555787

Abstract

The present paper aims to review the epidemiological literature regarding temporomandibular disorder (TMD) in order to determine which subgroups of the general population are more likely to suffer from TMD and why this might be the case. A literature search from the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed Database for relevant papers was conducted with pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Chosen articles that fulfilled the search criteria were compiled in tables and quality graded according to the QUADAS tool. A total of 42 articles were included and grouped into gender, age and psychological influences on TMD. It was found that TMD is the most common orofacial pain condition of non-dental origin. From the studies assessed, a two-to four-fold higher prevalence of TMD in women was noted with the prevalence peaking between the ages of 25-45. The higher prevalence rates for women indicated that possible biological, psychological, and/or social factors associated with the female gender increased the risk of TMD. It is evident that TMD is a significant and increasingly prevalent disorder found within the general population that appears more commonly in women and more common during the reproductive years. The available data highlights the need for further research on etiologic factors associated with TMD.

Keywords: Temporomandibular Disorders; Systematic review; Prevalence; Epidemiology

Introduction

In recent times temporomandibular disorders (TMD) has been identified as a frequent pathological disorder and awareness of this has amplified within the general population. TMD is a term encompassing a broad range of related pathologies of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) involving the masticatory muscles and associated structures. TMD is characterized by symptoms such as muscle tenderness, TMJ sounds, deviations or restrictions in the mandibular range of motion and associated headaches [1].

The prevalence of TMD has been comprehensively studied over the years, however, multiple difficulties (differing levels of skill between examiners, inconsistencies in judgments and research bias) arise when evaluating the results from a wide range of literature. The exact etiology of TMD has for many years been the center of debate, therefore many propose a multifactorial cause for the disorder. These have included, stress [2-9], age [10-14], gender [15-18], occlusion [19], parafunction [6,8], airway compromise [20] and psychological and psychosocial factors [2,7,21-23]. Furthermore, systemic problems such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory conditions, ankylosing spondylitis and lupus [1,4,24] have also been implicated.

Epidemiological studies in multiple countries (America, Sweden, Netherlands, Finland, Pakistan, India, Italy, Iran, Denmark, Brazil, United-Kingdom and Canada) have outlined a substantial prevalence of orofacial pain symptoms in the adult population, showing that approximately 5-60% of the population suffers from at least one of the signs of TMD [25-27]. The aim of this review is to analyze the epidemiological literature in order to determine which subgroups of the population are more likely to suffer from TMD and why this maybe the case.

Methods

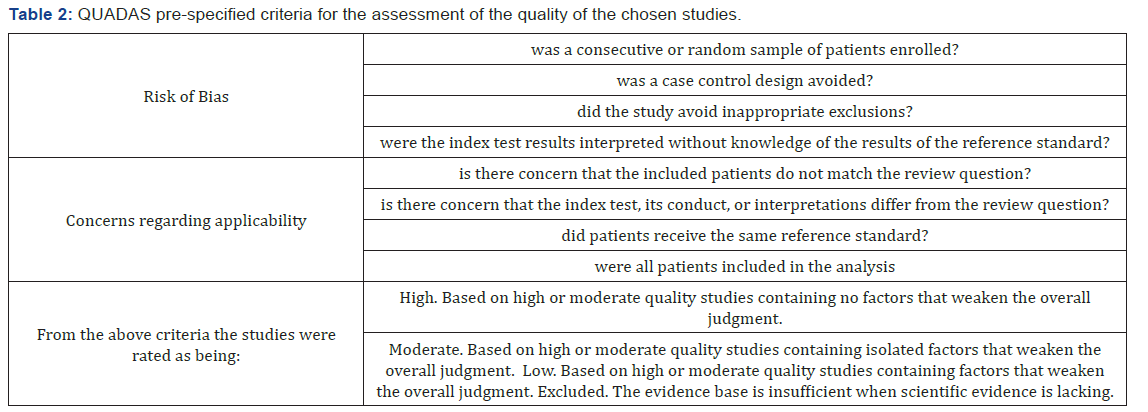

An electronic literature search of the US National Library of Medicine (PubMed) database and the Charles Sturt University Library was conducted (Figure 1). This review was restricted to full reports no older than 1995 on human subjects with letters, editorials and abstracts being excluded. Observational studies (cross-sectional surveys, cohorts and longitudinal studies) and previously published literature reviews were included. Epidemiological studies where subjects were representative of the general population were also included but studies were excluded when it was not possible to identify the source of the population. The protocol of this systematic review complies with PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews.

Search strategy

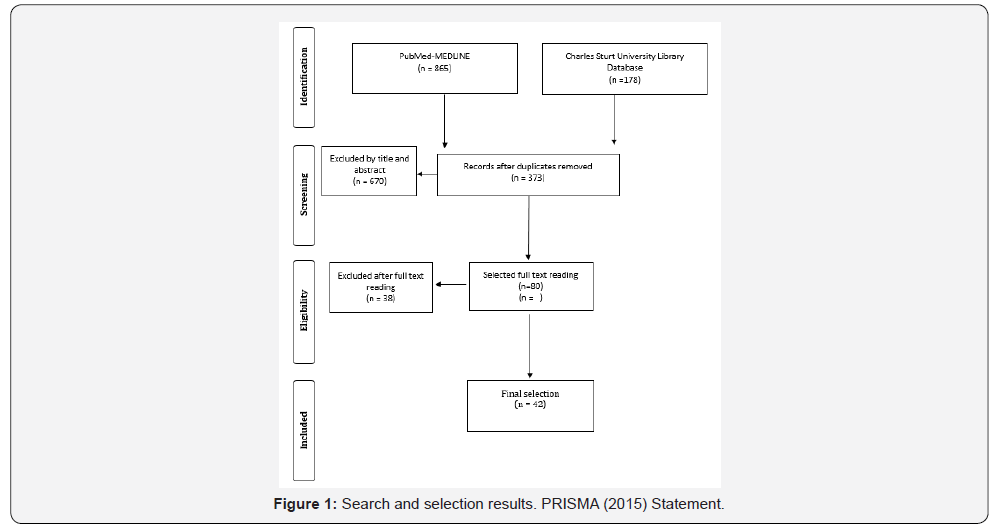

For the complete search strategy, electronic databases were queried (Table 1). Two internet sources were used to search for suitable papers that fulfilled the study purpose. These sources comprised the National library of Medicine, Washington, D. C (MEDLING- Pubmed) and the Charles Sturt University Library Data base. Both databases were searched for eligible studies up to an including August 2015. The designed search started was developed to include any systematic reviews, or population based studies on the epidemiology of TMD. All the reference lists were hand searched for further published work that could possible meet the eligibility criteria of the study.

Screening and selection

The searched studies titles and abstracts were screened for eligible papers. If the papers title or abstract were deemed eligible the paper was selected for further reading. If eligibility aspects were cited in the title, the abstract was read in detail to screen for appropriateness. After selection, the full papers were read in detail. The papers that satisfied the selection criteria were processed for data extraction.

Quality Assessment

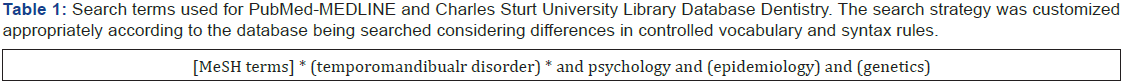

The chosen studies included in this review were assessed using the QUADAS tool [28] with each included study being rated as high, moderate or low quality according to the pre-specified criteria which can be found in the appendix (Table 2).

Results

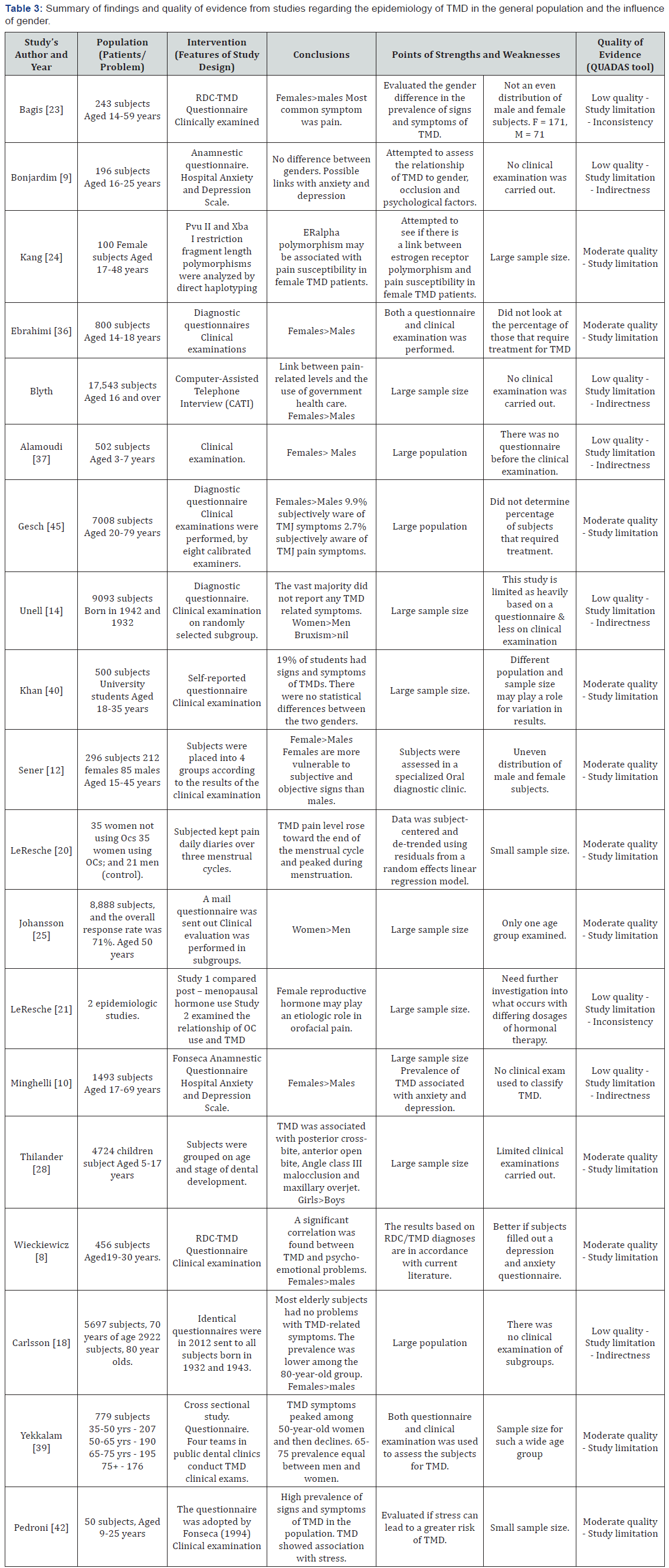

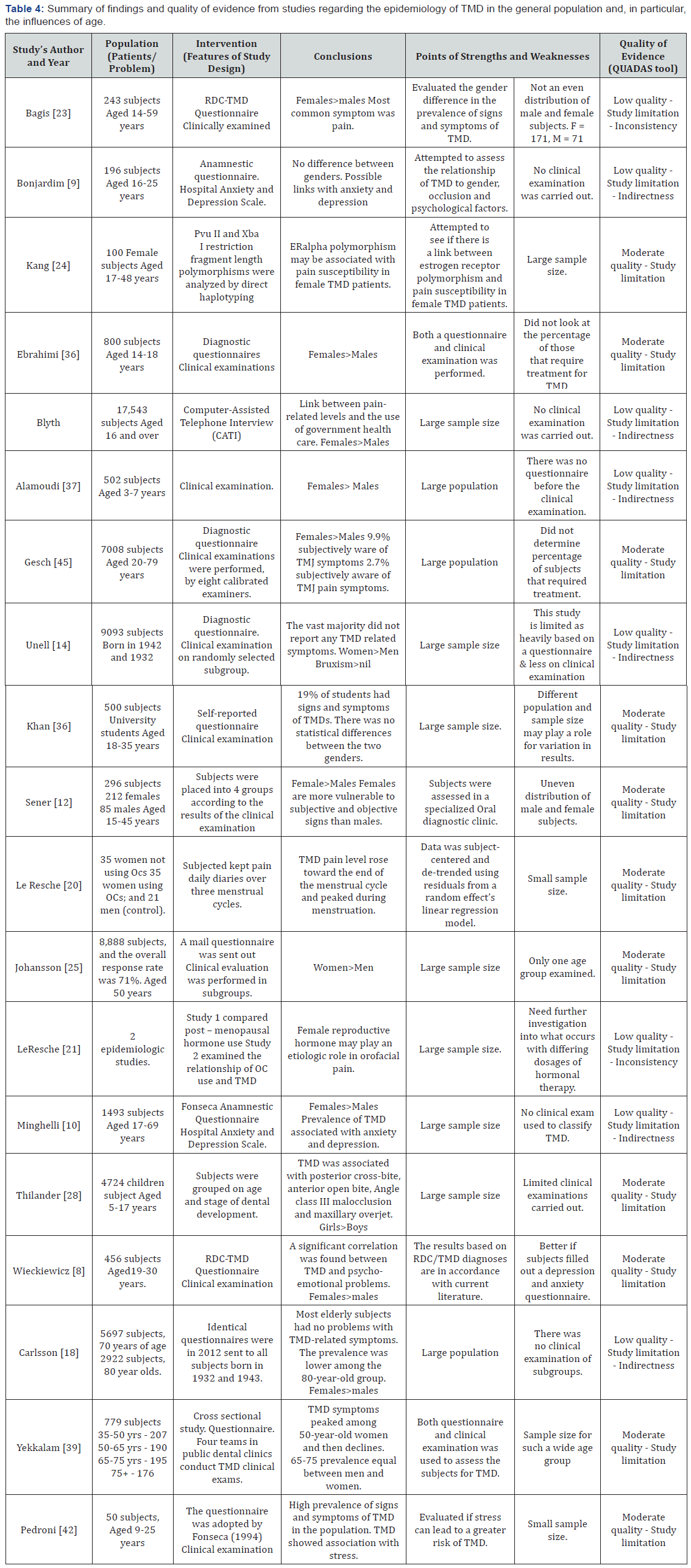

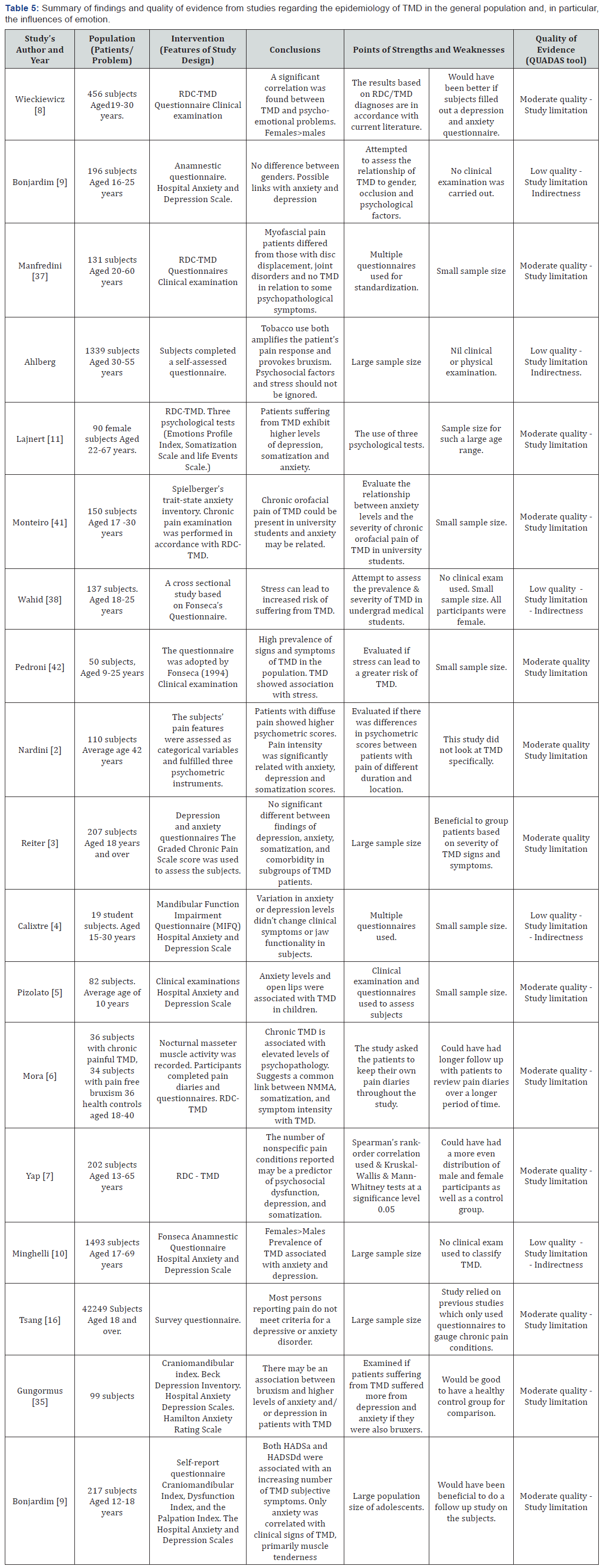

After examination of the full text articles, 42 articles were chosen for inclusion in the literature review (Figure 1). It was noted that when reviewing the epidemiology of TMD in the general population there seemed to be three main recurring influences (gender, age and emotional/psychosocial status) on TMD, which guided the decision to split the review into these three main influences. Therefore, the studies included in the review were grouped into gender influence (N=19) age influence (N=14) and psychological influence (N=18) on the epidemiology of temporomandibular disorders in the general population. The results were tabulated into three tables with each table summarizing the findings from the chosen studies according to these three main influences on TMD. Note that some studies, which were assessed, did overlap with these influences and thus may be found in multiple tables.

Of the selected 42 articles assessed there were no articles to be found of high quality, 28 to be found of moderate quality and 14 to be found of low quality. Elements that weakened the quality of evidence included: study limitations, inconsistency, and indirectness. Study limitations were recorded if there was any sign of publication bias, insufficient statistical analysis, uncertainty about blinding of the outcome assessor or any associated limitation in the methods of the study. If a single predictor or a method model was not validated indirectness was recorded. Inconsistency was recorded if there was a large variability in the results or if confidence intervals were wide. One study limitation that was taken into consideration is that many studies deem that any one symptom of TMD is enough to diagnose a subject with TMD. In this review at least two symptoms or a single painful symptom was required for inclusion in the review.

A summary of the studies with their quality of evidence and associated weaknesses and strengths are presented in Tables 3-5.

Discussion

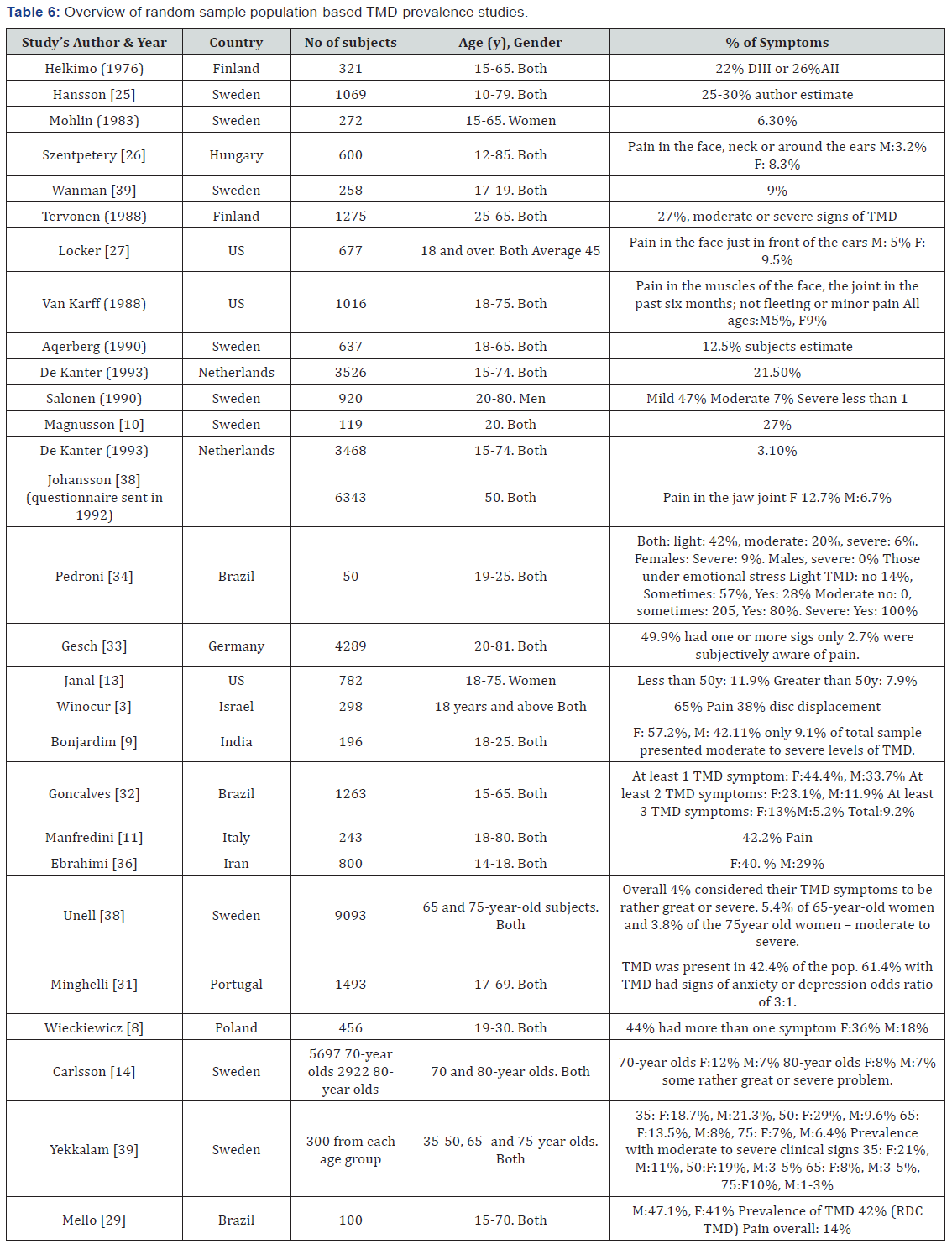

The general prevalence of orofacial pain symptoms in the adult population is substantial, with many studies claiming that approximately half of the population suffers from at least one of the signs of TMD [8,9,24,29-33]. A randomized population study carried out in Germany which looked at 7,008 subjects showed that half of the subjects had one or more clinical signs of TMD [33]. Studies assessed in this review showed the prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMD in the general population varied greatly, ranging from 1% to 75%, when established on clinical evaluation, and 6% to 75% when based on pain questionnaires only [8,9,24,29-34]. It is possible that such differences stem from the disparities in the population studies, or as a result of the different methods and clinical criteria used in the various studies. These differing prevalence figures on reported TMD symptoms can be seen in the various investigations, reflecting differences in study populations, definitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria and methodology used (Table 6) [35]. Epidemiological studies of TMD have reported further difficulties in creating a standardized pattern in the distribution of the disease, as well as standardizing the definition of TMD.

When reviewing the literature, it was found that there are three main factors that should be considered when looking at the epidemiology of TMD. These include gender, age and emotional or psychosocial status. We will explore the significance of these 3 major influences further in order to determine which subgroups of the population are more likely to suffer from TMD and why this maybe the case.

Gender influences

In general, it was determined from the studies selected for this review that women suffer more from TMD than men. This is consistent with many of the previous studies [26,27]. A study conducted on university students in Brazil found that 68% of all subjects exhibited some degree of disorder with 43.7% of subjects exhibiting audible TMJ sounds [34]. In this study the prevalence of TMD in women was almost four times greater than men. Many studies observed similar results and found that TMD seems to be far more prevalent in the female population (Table 3) [16,17,19,31,33,34,36-39]. Among all the studies analyzed only two studies did not find any statistically significant differences between males and females (Table 3) [9,40] Of these two studies one of them was deemed to be of limited quality as no clinical evaluation was carried out on any of the subjects [9].

These higher prevalence rates for women indicate that possible biological, psychological, and/or social factors associated with the female gender, increases the risk of TMD. One hypothesized reason for women suffering a higher prevalence of TMD is the physiological variances of the female, including hormonal variations, different characteristics of the connective tissue, and brain function and structure [8,34,41].

The greatest peak in the development of symptoms is apparent between 20 and 40 years of age, or during the reproductive period. Thus, it has been claimed, that the prevalent patterns of TMD may be affected by reproductive hormones [16]. The occurrence and severity of TMD pain has been said to be like that of migraine, where hormonal factors are also thought to account for some of the gender difference in prevalence rates [16].

On another note, one study has confirmed that there is many estrogen and progesterone receptors within the intra-articular cartilage in women with TMD [8]. Recently, locally synthesized estrogens have been found and demonstrated to contribute greatly to the function of cartilage [18]. Since the 1990s, the impact of estrogen deficiency on the development of TMD has also been researched [42,43] demonstrating, at least in rats and mice, that substantial alterations, such as the thickness of TMJ cartilage, flattened condyles, decreasing volume of subchondral bone, and general degenerative signs were observed after ovariectomy [42]. One study found that a drop in estrogen levels may be associated with changes in specific neurotransmitters believed responsible for the cause or potentiation headaches and TMD [16]. Studies however have additionally presented possible correlations between increases in estrogen levels and a subsequent increase in TMD symptoms [15-18]. Another possible mechanism by which estrogen can modulate pain levels, is via a direct effect on the expression and properties of ion channels in TMJ neurons [15]. This can lead to the neurons becoming more sensitized resulting in a lowered action potential threshold.

Other studies have discovered gender differences in brain structure and its possible connection with pain manifestation. For example, it has been noted that in many cases women have smaller hippocampal volumes when compared to men, and such patients report more severe acute or chronic pain.

Age influences

Several cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that the overall prevalence of TMD is significantly higher in the 20-40 year age group when compared with other age brackets [11,31,39,44]. The overall prevalence of TMD in children and adolescents differs greatly between multiple studies (Table 4) [1,10,11,13,14,19,29, 32,33,35,38,39,44]. The reason for the disparity in results when looking at the younger population in relation to TMD like other pain conditions is the fact that many of the questionnaires and examinations are tailored to the adult population. Children often have difficulty in understanding some of the questionnaires and can be confused by the examinations. Research looking at TMD in over 1000 young children (3-7 years) found that 14% of males and 18% of females suffered from TMD [1,37]. A study of 4724 children in Sweden aged 5-17 years showed 25% of participants experienced one or more TMD symptoms [19].

One study has claimed that TMD prevalence was inversely proportional to age [13]. This study also found that prevalence varies with socio economic status, race and particularly Hispanic ethnicity [13]. Another study, investigating if there is a tendency for TMD-related symptoms to decrease with age, found the prevalence to be lower among the over 80-year-old subjects when compared with the over 70-year-old subjects of both sexes [14]. A further study in 2010 found that at least two distinct age peaks (30s and 50s) are identifiable within the population suffering from TMD [10].

Emotional and psychosocial influences

Multiple studies found that TMD shares significant association with levels of anxiety and depression (Table 5) [2,5- 9,21,23,24,30,31,34,45,46]. Of all studies reviewed, only three found no association between emotional and psychosocial influences on TMD [3,4,12] with one of the studies having only 19 subjects [4], whilst the remaining two used sole questionnaires to gauge TMD and chronic pain conditions [3,12]. A study in 2003 [34] reported that all the individuals with moderate and severe TMD suffered from high emotional stress. The significance of psychological factors, such as increased anxiety, depression, and stress has been accentuated in literature describing the etiology of TMD and oral parafunctions [8,9,24,30,34,46]. A recent study investigating the significant role of psycho-emotional factors in the development of TMD, found that easily excitable and emotionally burdened persons suffered significantly more often from TMD and oral parafunctions [8].

It has been demonstrated that emotional stress increases the activity of the masticatory muscles leading to teeth clenching and producing resultant circulatory changes in the mastication muscles, which can consequently result in issues such as TMD [45].

A remarkable, and yet worrying finding, suggests that regularly used antidepressants, known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, may contribute to the cause of headaches and muscle pain [22]. A study showed that the development of bruxism was coupled with the appearance of neuroleptic-induced akathisia which occurs as a side-effect of antipsychotic drug treatment [22]. Evidence is showing that in many cases, repressed or unsettled and unresolved emotional problems play a key role in the continuation of TMD. These unresolved emotions generate stress, which may form obstructions and reduced flow of peptide signals that help preserve function at the cellular level, leading to dysfunction and pathology [7].

The changing epidemiology of TMD

Among the many controversies related to TMD, it has been established that the approximation of the overall prevalence of TMD in the general population has varied significantly. It was noted that older studies found smaller percentage of the population suffered from TMD when compared to the more recent studies [10]. Table 4 in the appendix, which has studies that were excluded due mainly to their age, outlines the changing prevalence over the years. These results also show the broad range of prevalent factors reached due to the limitations addressed previously. There does, however, appear to be an increase in people suffering from TMD in the general population as can be seen from some of the more recent population studies [9,11,32,33,36]. A large longitudinal cross-sectional study was carried out to look at possible trends in the prevalence of TMD symptoms in an adult population over two decades, from 1983 to 2003 [35]. This study found a statistically significant increase in TMD prevalence over the 20 year period. According to the study TMD symptoms increased over the 20-year period from 27% to 38%. It was found that 10.5% of the study population suffered from severe TMD symptoms in 1983 and in 2003 this increased to 16%. The study also found the incidence of headaches was more than twice as high as it was 20 years prior. From the literature, we can thus reasonably assume that the percentage of the population suffering from TMD is on the rise.

Limitations of current epidemiological studies and final remarks

The present review article shows that there is a large percentage of the population suffering from TMD, younger females and those suffering from depression and/or anxiety. It was seen that the prevalence of TMD signs and symptoms is consistent with much of the literature about the distribution of the symptoms according to age and gender. Many of the authors consider that using any single symptom as suggestive of TMD may lack specificity. When assessing the prevalence of four or more TMD symptoms, or what some authors considered severe TMD, many studies found approximately 10% of the population were affected [24,32,35,38,39]. However simply outlining several symptoms as a way of correlating the severity of TMD has its many limitations. These issues are what makes the study of the epidemiology of TMD so difficult and it is why as mentioned previously that in this review at least two symptoms or a single painful symptom was required.

There are multiple difficulties faced when looking at the prevalence and epidemiology of TMD, several of which include examiners with differing levels of skill, knowledge and experience, inconsistencies in judgments and research bias. Another major issue in determining the overall prevalence of TMD within a population is that the division between disease and non-disease is not always clear. Further to this, the overall conception of TMD is unclear to most clinicians, as it is a collective term, which incorporates numerous clinical pathologies or disorders that involve the TMJ and its associated structures.

TMD constitutes several pathologies rather than just one condition, with comparable signs and symptoms. Considerations in the complicated interrelationships between the TMJ, teeth, muscles, cervical spine, autonomic nervous system and the higher centers of the brain in temporomandibular disorders are essential. Such an unusual classification and description of a group of disorders that affect such a vast amount of people in the population effectively assures misunderstandings from the perspective of epidemiology and research into this subject.

Conclusion

From this review we can conclude that TMD is the most common orofacial pain condition of non-dental origin. However, the actual TMD prevalence at the population level is a matter of debate. This review did however outline that, the prevalence peaks between the ages of 25-45, women suffer more than men and added psychosocial issues lead to a greater prevalence and intensity of TMD symptoms. It was also noted that there seems to be an increase in TMD prevalence in the general population over recent decades. Additional repeated population-based investigations covering extended time periods would help add important information in these areas and further validate the findings. Also established, is the significance of a TMJ assessment in the overall examination of the patient, especially at a young age. Recognizing a potential TMD problem at an early stage may allow intervention to avoid further complications. Future studies should be adequately sized for accurate determination of the prevalence and detection of important associated factors. Data on potential risk factors and cofounders such as age, gender and emotional/ psychosocial status should also be collected and adjusted for in the statistical analysis of future studies.

Acknowledgement

We would like to sincerely thank Professor Greg Murray, The University of Sydney and Professor Manabu Morita, Okayama University, Japan for their kind assistance in the review of the original manuscript.

References

- Widmalm S, Christiansen s, Gunn S (1999) Crepitation and clicking as signs of TMD in preschool children. Cranio 17(1): 58-63.

- Nardini L, Pavan C, Arveda N, Ferronato G, Manfredini D (2012) Psychometric features of temporomandibular disorders patients in relation to pain diffusion, location, intensity and duration. J Oral Rehabil 39(10): 737-743.

- Reiter S, Emodi-Perlman A, Goldsmith C, Friedman-Rubin P, Winocur E (2015) Comorbidity between depression and anxiety in patients with temporomandibular disorders according to the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 29(2): 135-143.

- Calixtre L, Gruninger B, Chaves T, Oliveira A (2013) Is there an association between anxiety / depression and temporomandibular disorders in college students? J Appl Oral Sci 22(1): 15-21.

- Pizolato R, Freitas-Fermandes F, Gaviao M (2013) Anxiety/Depression and orofacial myofacial disorders as factors assocaited with TMD in children. Braz Oral Res 27(2): 155-162.

- Mora S, Weber D, Borkowski S (2012) Nocturnal masseter muscle activity is related to symptoms and somatization in temporomandibular disorders. J Psychosm Res 73(4): 307-312.

- Yap A, Chua E, Dworkin S, Tan H, Tan K (2002) Multiple pains and psychosocial functioning/psychological distress in TMD patients. Int J Prosthodont 15(5): 461-466.

- Wieckiewicz M, Grychowska N, Wojciechowski K, Pelc A, Augustyniak M, et al. (2014) Prevalence and Correlation between TMD based on RDC/TMD diagnoses, oral oarafunctions and psychoemotional stress in Polish university students. BioMed Res Int 14: 1-7.

- Bonjardim LR, Lopes-Filho R, Amado G, Albuquerque R, Goncalves S (2009) Association between symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and gender, morphological occlusion, and psychological factors in a group of university students. Indian J Dent Res 20(2): 190-194.

- Magnusson T, Egermark I, Carlsson G (2000) A Longitudinal Epidemiologic Study of Signs and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders from 15-35 Years of Age. J Orofac Pain 14(4): 310-319.

- Manfredini D, Piccotti F, Ferronato G, Guarda-Nardini L (2010) Age peaks of different RDC/TMD diagnoses in a patient population. J Dent 38: 392-399.

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, Alonso J, Karam E, et al. (2008) Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 9(10): 883-891.

- Janal MN, Raphael KG, Nayak S, Klausner J (2008) Prevalence of myofascial temporomandibular disorder in US community women. J Oral Rehabil 35(11): 801-809.

- Carlsson G, Ekback G, Johansson A, Ordell S, Unell L (2014) Is there a trend of decreasing prevalence of TMD-related symptoms with ageing among the elderly? Acta Odont Scand 72(8): 714-720.

- Wang J, Chao Y, Wan Q, Zhu Z (2008) The possible role of estrogen in the incidence of temporomandibular disorders. Med Hypotheses 71(4): 564-567.

- LeResche L, Mancl L, Sherman J, Gandara B, Dworkin S (2003) Changes in temporomandibular pain and other symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Pain 106(3): 253-261.

- LeResche L, Saunders K, Von Korff M, Barlow W, Dworkin S (1997) Use of exogenous hormones and risk of temporomandibular disorder pain. Pain 69(1-2): 153-160.

- Yu S, Xing X, Liang S, Ma Z, Li F, et al. (2009) Locally synthesized estrogen plays an important role in the development of TMD. Med Hypotheses 72(6): 720-722.

- Thilander B, Rubio G, Pena L, de Mayorga C (2002) Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction and its association with malocclusion in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic study related to specified stages of dental development. Angle Orthod 72(2): 146-154.

- Perkins J, Sie K, Milczuk H, Richardson M (1997) Airway management in children with craniofacial anomalies. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 34(2): 135-140.

- Gungormus Z, Erciyas K (2009) Evaluation of the relationship between anxiety and depression and bruxism. J Int Med Res 37(2): 547-550.

- Amir I, Hermesh H, Gavish A (1997) Bruxism secondary to antipsychotic drug exposure: a positive response to propranolol. Clin Neuropharmacol 20(1): 86-89.

- Manfredini D, Bandettini di Poggio A, Cantini E, Dell’Osso L, Bosco M (2004) Mood and anxiety psychopathology and temporomandibular disorder: a spectrum approach. J Oral Rehabil 31(10): 933-940.

- Wahid A, Mian FI, Razzaq A, Bokhari S, Kaukab T, et al. (2014) Prevalence and severity of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) in undergraduate medical students using Fonseca’s questionnaire. Pak Oral Dent J 34(1): 38-41.

- Hansson T, Nilner M (1975) A study of the occurrence of symptons of disease of the temporomandibular joint masticatory musculature and related structures. J Oral Rehabil 2(4): 313-324.

- Szentpetery A, Huhn E, Fazekas A (1986) Prevalence of mandibular dysfunction in an urban population in Hungary. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 14(3): 177-180.

- Locker D, Slade G (1988) Prevalence of symptoms associated with temporomandibular disorders in a Canadian population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 16(5): 310-313.

- Whiting P, Rutjes A, Reitsma J, Bossuyt P, Kleijnen J (2003) The development of QUADA: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in the systematic reviews. Med Res Methodol 3.

- Mello VV, Barbosa AC, Morais MP, Gomes SG, Vasconcelos MM, Caldas Junior Ade F (2014) Temporomandibular disorders in a sample population of the Brazilian northeast. Braz Dent J 25(5): 442-446.

- Monteiro D, Zuim P, Pesqueira A, Ribeiro P, Garcia A (2011) Relationship between anxiety and chronic orofacial pain of temporomandibular disorder in a group of university students. J Prosthodont 55: 154-158.

- Minghelli B, Morgado M, Caro T (2014) Association of temporomandibular disorder symptoms with anxiety and depression in Portuguese college students. J Oral Sci 56(2): 127-133.

- Goncalves DA, Dal Fabbro AL, Campos JA, Bigal ME, Speciali JG (2010) Symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in the population: an epidemiological study. J Orofac Pain 24(3): 270-278.

- Gesch D, Bernhardt O, Alte D, Schwahn C, Kocher T, et al. (2004) Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in an urban and rural German population: results of a population-based Study of Health in Pomerania. Quintessence Int 35(2): 143-150.

- Pedroni CR, De Oliveira AS, Guaratini MI (2003) Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in university students. J Oral Rehabil 30(3): 283-289.

- Kohler A, Hugoson A, Magnusson T (2012) Prevalence of symptoms indicative of temporomandibular disorders in adults: cross-sectional epidemiological investigations covering two decades. Acta Odontol Scand 70(3): 213-223.

- Ebrahimi M, Dashti H, Mehrabkhani M, Arghavani M, Daneshvar-Mozafari A (2011) Temporomandibular Disorders and Related Factors in a Group of Iranian Adolescents: A Cross-sectional Survey. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospect 5(4): 123-127.

- Alamoudi N, Farsi N, Salako N, Feteih R (1998) Temporomandibular disorders among school children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 22(4): 323-328.

- Unell L, Johansson A, Ekback G, Ordell S, Carlsson GE (2012) Prevalence of troublesome symptoms related to temporomandibular disorders and awareness of bruxism in 65- and 75-year-old subjects. Gerodontology 29(2): e772-e779.

- Yekkalam N, Wanman A (2014) Prevalence of signs and symptoms indicative of temporomandibular disorders and headaches in 35-, 50-, 65- and 75-year-olds living in Vasterbotten, Sweden. Acta Odontol Scand 72(6): 458-465.

- Khan M, Khan A, Hussain U (2015) Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) among university students. Pak Oral Dent J 35(5): 382-385.

- Maleki N, Linnman C, Brawn J, Burstein R, Becerra L, Borsook D (2012) Her versus his migraine: multiple sex differences in brain function and structure. Brain 135(Pt 8): 2546-2559.

- Okuda T, Yasuoka T, Nakashima M, Oka N (1996) The effect of ovariectomy on the temporomandibular joints of growing rats. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54(10): 1201-1210.

- Yamashiro T, Takano-Yamamoto T (1998) Differential responses of mandibular condyle and femur to oestrogen deficiency in young rats. Arch Oral Biol 43(3): 191-195.

- Balke Z, Rammelsberg P, Leckel M, Schmitter M (2010) Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders: samples taken from attendees of medical health-care centers in the Islamic Republic of Iran. J Orofac Pain 24(4): 361-366.

- Lajnert V, Franciskovic T, Grzic R, Kovacevic Pavicic D, Bakarbic D, et al. (2010) Depression, somatization and anxiety in female patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD). Coll Antropol 34(4): 1415-1419.

- Bonjardim L, Gaviao M, Pereira L, Castelo P (2005) Anxiety and Depression in Adolescents and Their relationship with Signs and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders. Int J Prosthodont 18(4): 347-352.