Clinical Outcomes and Economic Implications from the Revision Hip Arthroplasties Queue at a Brazilian Public Health System: A Cross-Sectional Study Focused on Patient Status, Waiting Period for Surgery and Bone Loss Severity

Locks R1, Villallba CMM2, Ourique DK2, Contreras MEK3, Fernandes DA4, Araujo LCT5, Figueiredo F6 and Cabral FMP7

1Orthopedic Hip Surgeon, Regional Hospital of São José, Santa Catarina, Brazil

2Orthopedic Resident, Regional Hospital of São José, Santa Catarina, Brazil

3Orthopedic Hip Surgeon, Celso Ramos Hospital, Santa Catarina, Brazil

4University Hospital Polydoro Ernani de Sao Thiago, Santa Catarina, Brazil

5Orthopedic Hip Surgeon, ENDO Klinic Berlin, Germany

6Biostatistician, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

7Research affiliate, Orthopedic department, Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

Submission: August 08, 2024; Published: August 28, 2024

*Corresponding author: Renato Locks, Orthopedic Hip Surgeon, Regional Hospital of São José, Santa Catarina, Brazil

How to cite this article: Locks R, Villallba CMM, Ourique DK, Contreras MEK, Fernandes DA, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Economic Implications from the Revision Hip Arthroplasties Queue at a Brazilian Public Health System: A Cross-Sectional Study Focused on Patient Status, Waiting Period for Surgery and Bone Loss Severity. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2024; 23(5): 556121. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2024.23.556121

Abstract

Importance: Orthopedics epidemiological studies are considered an important tool for management strategy in patients waiting for surgical treatment. Patients with indications for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and revision arthroplasties (rTHA) need efficient solutions for their highly complex surgeries. However, problems at many processes are still evident.

Objective: To present patients clinical and social-economic status at Santa Catarina state rTHA queue in 2021.

Design, Setting, and Participants: Observational, cross-section study conducted at Santa Catarina - Brazil, in adults with indication for rTHA.

Main Outcomes and Measures: The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), Harris Hip Score (HHS) and Paprosky Classification of Acetabular Bone Loss are the main outcomes measured. Key secondary outcomes are sex, age, waiting time on surgery queue and patient´s socio-economic status.

Statistical Methods: Patient characteristics were described according to the type of variable at a 5% significance level.

Background: Although THA is a common and successful surgical procedure, post-operative complications have been shown at different periods for different reasons, with the need for rTHA indication. Many aspects should be addressed for rTHA due to the high complexity of the procedure associated and patients’ clinical status. Brazilian public health system (SUS) provides universal access and the resolution capacity is still a challenge. The objective of the study is to evaluate the clinical and social-economic status of the patients on the waiting queue for a rTHA at Santa Catarina state - Brazil in 2021.

Results: Fifty-eight patients were evaluated. Mean age was 63 (+/-11) years. The mean HHS was 41 points (10-80). Waiting time on queue line was 3.5 years. The mean CCI was 3% (p: 0.5). Patients presented low educational level (p: 0.4) and low income (p: 0.3). Acetabular defects Paprosky 2C and 3A were the most prevalent.

Conclusion: The average patient was mainly elderly, retired, with low levels of education and income, who undergone at least one rTHA from aseptic acetabular loosening. This typical patient had at least 1 clinical comorbidity and a poor hip score reflecting their poor functional quality. An assured approach combining policy reform, administrative efficiency, and patient-centered care is needed to ensure timely and effective treatment for patients on a waiting queue for rTHA.

Keywords: Arthroplasties Queue; Cross-Sectional Study; Brazilian public health system; Telemedicine and Remote consultations; Patient-centered care

Abbreviations: THA: Total Hip Arthroplasty; Rtha: Revision Arthroplasties; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; HHS: Harris Hip Score; QoL: Quality of Life; BMI: Body Mass Index; SD: Standard Deviation; STROBE: Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a common surgical procedure worldwide, with more than 1 million surgeries performed globally each year [1] and a projected growth of 176% by 2040 [2]. Primary THA is a highly successful intervention with most indications related to aging such as osteoarthritis and femoral neck fracture [3]. Although associated with large improvements in joint function and health-related quality of life (QoL) [4], complications have been reported with a mean short-term risk of 2.4% that can raise up to 12% after 10 years of surgery [5]. In 2019, a meta-analysis carried out on 13.212 patients with and average age of 58 years demonstrated THA failures in 25% of cases between 15 to 20 years and 42% within 25 years, demonstrating the need for continuous strategies re-evaluations and technological advances to prevent an economic burden on the health care system [6].

Patients undergoing hip arthroplasties have been shown to suffer from comorbidities as high as 83% that can affect the outcome of the procedure [7]. The most common late indications for rTHA are aseptic loosening, polyethylene wear osteolysis, instability, fracture, chronic infection and pain, which depending on patients previous condition, morbidity and mortality can significantly increase [8]. Delaying a rTHA can lead to significant complications, including increased rates of implant loosening, infection and bone loss, resulting in a more complex surgical procedure and poorer overall outcomes [9].

We reassessed patients waiting queue for rTHA from the health public system at Santa Catarina state. Given the complexity related to the procedure and clinical status from the patients, the health care system resolution capacity is paramount. In Brazil, the unified health system (SUS) provides free public service, generating endless waiting queue for the so-called elective surgeries. Brazil has already reached 220 million people [10] and understanding the clinical and epidemiological profile from patients on a waiting queue is crucial to develop strategies for the medical needs.

Objectives and Aim

This observational cross-sectional study is to assess the clinical and socio-economic status of patients in Santa Catarina state who are currently waiting for rTHA. The study aims to classify the clinical status of these patients using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), evaluate bone loss through the Paprosky classification, and assess their socio-economic status based on education level, income and others. By analyzing these factors, the study seeks to identify potential correlations and disparities that could influence patient outcomes.

Patients and Methods

This was an observational, cross-sectional study at a single academic tertiary referral hospital. The study was approved by the ethics committee. We had 69 patients on a waiting list for rTHA with unknown or out-of-date clinical status and exams, including radiographic assessment. We attempt to contact all patients and we achieved a return of 58 (84%) at our hospital , that were interviewed, examined and routine exams made, between the period of March to April 2021. Collected data included patient age, sex, socioeconomic data, indications for primary THA, indications for revision THA, waiting time on queue for surgery, Harris Hip Score (HHS) [11], original Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [12] without considering age and Paprosky [13] classification. Body mass index (BMI) was not carried out due to the lack of a proper scale. There was clarification about the motivation of the study, as well as signing of the free and informed consent form. The complete radiographic assessment was evaluated separately and discussed until a consensus was reached by the surgeons from the hospital Hip Surgery group.

To describe the economic impact of the waiting time for the rTHA, an estimated value was made for patients of working age: the waiting time in the procedure queue was multiplied by the minimum wage value in force in may/2021 (US$207.50) [14]. In Brazil, patients are considered retired due to disability after 2 years, therefore an estimate of social security cost was calculated until the end of their work activity, women up to 62 years old and men up to 65 years old, according to legislation [14]. The estimated amount not collected from each taxpayer due to inability to work, considering the per capita income in Santa Catarina in 2021 was US$307.92 [15]. This value was multiplied by the number of months in which these patients were awaiting surgery, added to the number of months until the end of working age. The final values were added together for a final estimated value.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were described according to the type of variable: continuous variables were described as mean standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as frequency and proportion. The association between CCI and Paprosky was assessed using Fisher's exact test. All analyzes were performed at a 5% significance level. All hypothesis tests and confidence intervals calculated were two-tailed. This analysis was carried out using the software R, version 4.1.0. This paper followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [16].

Results

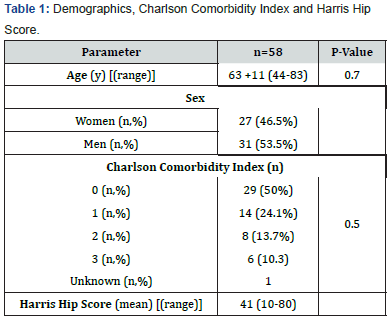

Fifty-eight patients waiting rTHA were interviewed. The mean (SD) age was 63 (+/-11) years and 27 patients were woman (46.5%). The mean Harris Hip Score (HHS) was 41 points, ranging from 10 to 80. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was 3%, where 50% of patients had no comorbidity. Fourteen patients (24.1%) scored 1 point, 8 patients (13.7%) scored 2 points and 6 patients (10.3%) had 3 or more points, with a p-value of 0.5 (Table 1). Lifestyle habits commonly associated with comorbidities such as smoking (16%) and alcoholism (3.4%) did not have significant statistical relevance (p: 0.5 and 0.9, respectively) with no difference between genders.

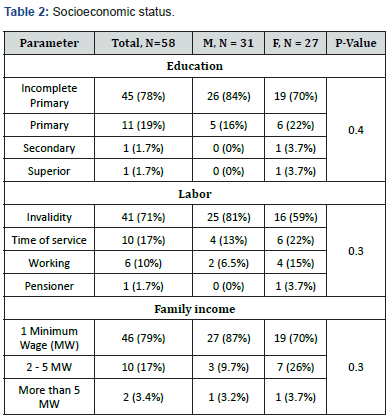

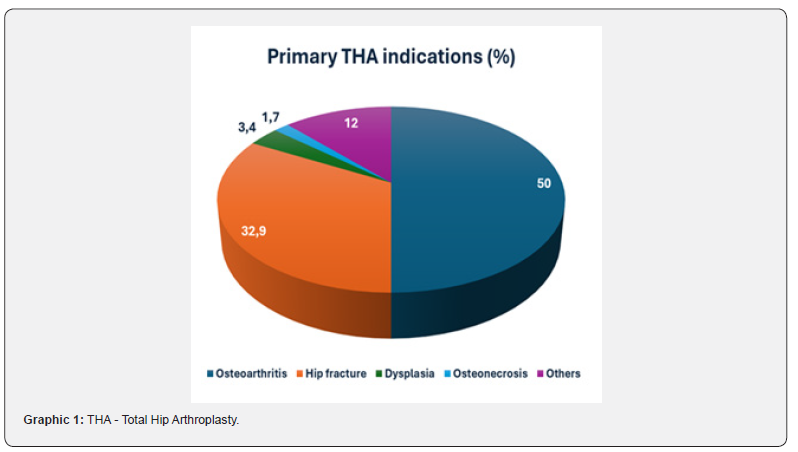

Patients’ socioeconomic status is shown at Table 2. Forty-five patients (78%) had incomplete primary education and 11 patients (19%) had completed it. One patient had completed secondary level and one had superior level. Patients were predominantly composed of low-income people, as 46 (79%) have an income up to 1 to 2 minimum wages. Most patients (90%) were retired, with disability being the cause cited by 41 of them (71%). Twenty-eight patients (48%) were at economically active age but retired due to disability. Of the patients interviewed, 29 (50%) had primary THA performed due to coxarthrosis and 19 (32.9%) due to femoral neck fracture (Graphic 1). Osteonecrosis was the main cause in two patients (3.4%) and Rheumatoid Arthritis in one patient (1.7%). In 7 patients (12%) we could not identify the past primary cause.

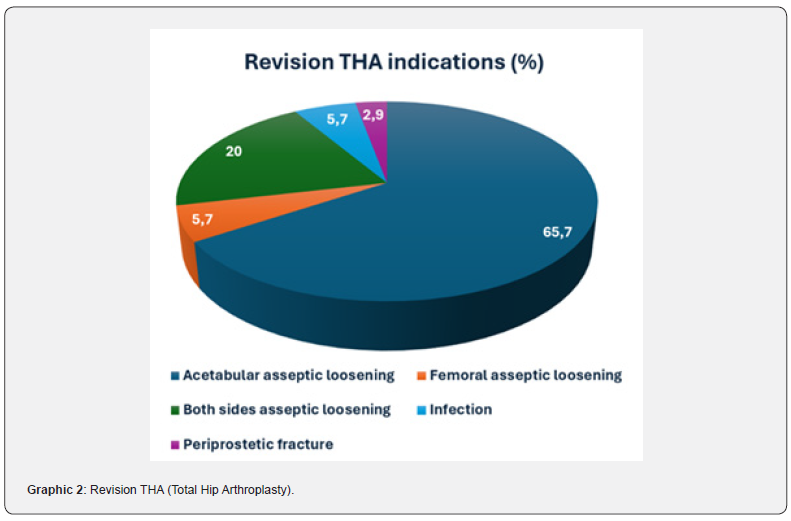

After a consensus among surgeons from the Hip surgery group from the identifiable cases, the most prevalent cause for revision was Aseptic Acetabular loosening, found in 65.7%. Revision for both components was the presumed indication in 20%. Infection and Aseptic Femoral loosening were the cause in 5.7%, respectively. Periprosthetic fracture was responsible for 2.9% of the indications (Graphic 2).

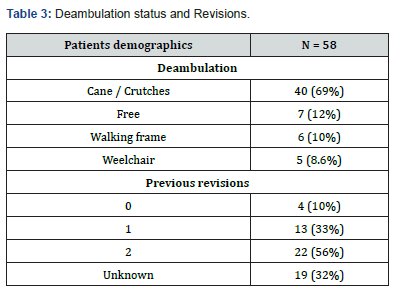

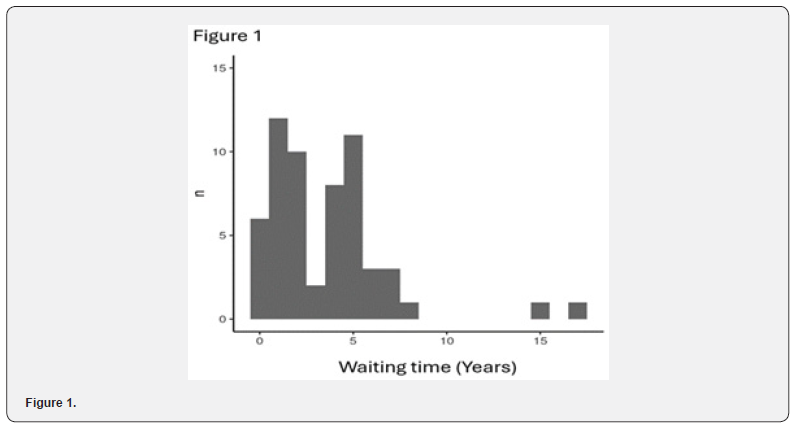

Related to walk, 46 patients (79.3%) needed some supportive device. Five patients (8.6%) were unable to walk. Only 7 patients (12%) could walk freely (Table 3). Related to the number of previous revisions precisely informed, 35 patients (89.7%) had undergone through at least one revision hip arthroplasty. Only 4 (10.3%) were not subjected to rTHA. Nineteen patients (32%) could not precisely confirm this information. The average waiting time for the rTHA was 3.5 years. The distribution of the awaiting time was bimodal (Figure 1), where two large groups of patients were identified waiting for 2 years and 6 years, respectively. Six patients (10%) were waiting for less than a year and two patients (3.4%) were waiting for more than 15 years.

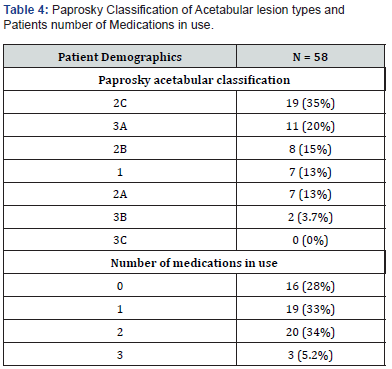

No correlation was found between CCI and the three most prevalent Paprosky types in the sample (2B, 2C and 3A) (Table 4). The occurrences of these three categories appear to be uniformly distributed in relation to the ranges considered for CCI, with no detectable association (p = 0.5). Forty-four patients (72.4%) were using at least one medication for pain relief, which non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were the most prevalent singly used by 18 patients (31%). When calculating the amount of money received in social security benefits from the moment of indication of the revision surgery until our evaluation, the estimated value was US$ 340,175.47. When extrapolating the benefits patients will receive until retirement a value of US$ 636,173,58 was calculated and the total sum of US$ 976,349.05 in social security benefits. Regarding the estimated values when these patients stop producing from the time the surgery was indicated until the end of their economically active age, a value of US$ 1,448,476.98 was obtained. Adding up all these values, total costs will be US$ 2,424,826.04.

Discussion

We explored the clinical and socio-economic status from patients in the waiting queue for a rTHA at a public health care system in Santa Catarina, Brazil. We have identified a burden on vulnerable populations with low income and low education, that impacts population's health, even though Santa Catarina has one of the highest human development index in Brazil [15,17]. The mean waiting time for rTHA found was 3.5 years and some patients were waiting for more than 15 years, exceeding by far the medically advisable period [18]. Prolonged waiting times for semi-urgent surgeries, including rTHA, are associated with worse post-operative outcomes as patients' conditions deteriorate [19].

The mean age was 63±11 years. Evans et al. [6] showed in a meta-analysis that the mean age for a THA was 58 years and by that we should question the durability of our arthroplasties. Life expectancy at Santa Catarina has reached 80 years of age [15]. We still did not implemented a National Registry of Arthroplasties, which makes it difficult to make population-based comparisons, although this project has already been carried out [20]. In order to develop better public policies based on registry data, we should develop a strategy to report at least 90% of our procedures [21], such as developed countries that achieves more than 95% [22].

According to a retrospective study made by Pattel et al at 400, 974 rTHA, the most prevalent comorbidities found were hypertension (59.74%), deficiency anemia (17.51%), chronic pulmonary disease (16.92%), fluid/electrolyte disorders (15.74%), and hypothyroidism (14.81%) [4]. We found that the most prevalent diseases were Diabetes Mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. We used the CCI for the risk of mortality in one year as a comorbidity evaluation score. The higher the score, the more likely the predicted outcome will result in mortality or higher resources used [12]. Patients at our study presented a mean value of 3% risk of dying in one year by this index. Fifty percent of them did not have any comorbidity points. Therefore there was no statistical correlation between CCI and time on queue, but we presented a cross-sectioned evaluation. We did not compare patient´s status since the first indication of revision and this maybe a drawback. Also, the mean age was 63, which should be considered low for a patient that had already undergone through a rTHA. Prolonged waiting time for hip rTHA often develop high comorbidity, further complicating their overall health and the outcomes of the surgery. The presence of higher CCI score (2 or more comorbidities) at ¼ of the patients queue should be considered high and a risk factor for 90-day readmission and surgical complications [23]. Also, there is a strong association between infection and comorbidity, with level tailored patient-specific guidelines taking comorbidity into account to potentially improve in-hospital outcomes [24].

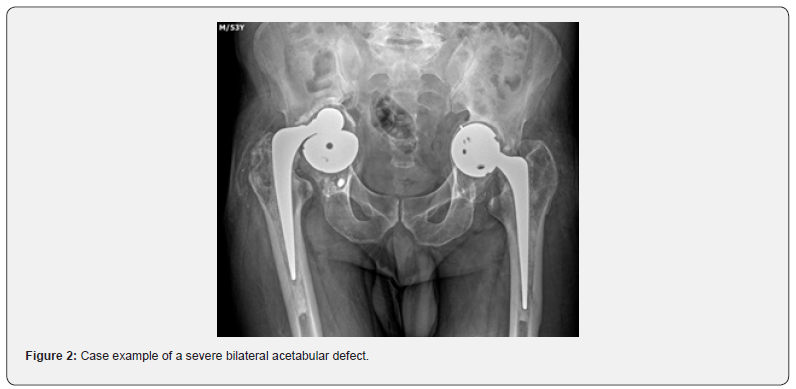

Regarding of bone defects, according to Paprosky classification [13] we have found a more severe proportion of lesions on the acetabular side: types 2B, 2C and 3A (case example figure 2) in decreasing order of frequency, while in the femoral side types 1 and 2 were more prevalent. Similar incidence was previously reported by Guimaraes et al [25], which demonstrated a prevalence in decreasing scale of acetabular defect types 3A, 2A and 2B. Extended time on a waiting queue for revision hip arthroplasty is often correlated with worsening acetabular defects, as prolonged delays can lead to increased bone loss and joint degeneration, complicating the surgical intervention and potentially compromising the long-term outcomes [26].

When calculating the amount of money received in social security benefits, the total amount was US$ 976,349.05. Regarding the estimated values when these patients stop producing from the time the surgery was indicated until the end of their economically active age, a value of US$ 1,448,476.98 was obtained. Adding up all these values, total costs will be US$ 2,424,826.04. Bohm et al revealed that 20% of people under the age of 65 were away from the workforce due to deteriorated hip function while awaiting surgery [27]. This study did not survey the costs related to medications, transportation of patients to consultations and surgeries, as well as the cost of the revision surgery to be performed. No reference to these values was found in our national literature. Yao et al demonstrated in a recently research that a rATQ costs an average of $24,630.00 and when the rATQ is due to infection the cost of the procedure more than doubles, rising to around $58,369.00 [28]. When discussing rATQ review by SUS, there is a consensus that it is a high-cost procedure; however, as demonstrated, there are other additional costs that are not normally computed that further increase the final cost of this surgery, substantially aggravated by the long waiting time. The findings of this study, while specific to the Brazilian public health system, may have broader implications for other low- and middle-income countries facing similar challenges. The systemic issues from public administrative organization, resource allocation and economic constraints that hinder effective healthcare delivered are not unique to our country. Therefore, epidemiological studies lead to a reflexive socio-economic and healthcare context, providing a more robust basis for policy recommendations.

At the moment in Brazil, officially more than 8,000 patients are waiting for a THA [29]. This number is probably much higher because this data was obtained from only 16 states out of 27. The restrained demand for rTHA is probably over 4 digits, considering that the relation between THA and rTHA is approximately 1:10 [30]. This study is not without limitations. The lack of updates and changes in patient registration data, such as telephone number and address, were obstacles to conducting the study. Also, the study was conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic and some patients chose not to participate due to fear of contagion, difficulties in getting around and locomotion. Since this was a cross-sectional study with the application of a questionnaire and clinical evaluation in a sample of patients who were mostly elderly and low levels of education, obtaining some more specific information may have been compromised due to difficulty in understanding, especially regarding previous surgeries and treatments. This study only reflects the profile of patients from a SUS at a referral center. Patients are usually referred to this center when they have bone failure due to osteolysis or infection, which requires bone grafting. Also, the data used was retrospective and relied on records from public health institutions, which may be subject to inaccuracies or incomplete information. Secondly, the study was conducted within a specific time frame and geographical area, potentially limiting its applicability to other regions of Brazil or other periods. The lack of a control group or comparison with private healthcare systems also limits the ability to generalize findings across different healthcare models. Additionally, the study did not fully account for the potential influence of cultural factors, such as patient expectations and behaviors, which could significantly impact waiting times and treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

The average patient´s profile was composed mainly by elderly people, retired due to disability, with low levels of education and low income. Most of them had already undergone at least one revision for aseptic acetabular loosening, which was originally performed due to coxarthrosis. Their walking was often performed with the use of a cane or crutches and typically waiting for hip revision for a few years with the majority diagnosis of aseptic acetabular loosening. This typical patient had at least 1 clinical comorbidity, a poor hip score reflecting their poor functional quality and the presence of a severe acetabular bone defect.

This study highlighted some systemic challenges in the Brazilian public health system, concerning elective rTHA. It reinforced the notion that economic and administrative barriers significantly influence healthcare delivery in low- and middle-income countries. The study's findings challenge the existing public health queues, revealing some complex factors involved. This understanding calls for a reevaluation of current practices and policies within the SUS and other similar healthcare systems globally.

Future research should build on these observations by exploring potential solutions to the identified challenges. This could include studies on the effectiveness of different queue management strategies, such as triage systems that prioritize based on clinical urgency rather than the order of entry. Changing the classification of rTHA from an elective procedure to semi-urgent could be another pathway. Additionally, research into the role of telemedicine and remote consultations in improving access to specialized care for rural populations could be invaluable. Investigating the economic impact of delayed surgeries on both the healthcare system and patients could also provide a stronger case for policy changes. Moreover, the implementation of a National Registry for Hip Arthroplasty and related research studies to track patient outcomes, identifying trends, and guiding policy decisions.

In conclusion, addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach, combining policy reform, administrative efficiency, and patient-centered care to ensure timely and effective treatment for patients on a waiting queue for rTHA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this work do not have any conflicts of interest that could influence the results obtained.

References

- Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP (2018) Projected Volume of Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty in the US, 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg 100(17): 1455-1460.

- Shichman I, Roof M, Askew N, et al. (2023) Projections and Epidemiology of Primary Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in Medicare Patients to 2040-2060. JBJS Open Access 8(1): e22.00112.

- Nho SJ, Kymes SM, Callaghan JJ, Felson DT (2013) The Burden of Hip Osteoarthritis in the United States: Epidemiologic and Economic Considerations. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 21(Suppl): S1-S6.

- Patel I, Nham F, Zalikha AK, El-Othmani MM (2023) Epidemiology of total hip arthroplasty: demographics, comorbidities and outcomes. Arthroplasty 5(1): 2.

- Ferguson RJ, Palmer AJ, Taylor A, Porter ML, Malchau H, et al. (2018) Hip replacement. Lancet 392(10158): 1662-1671.

- Evans JT, Evans JP, Walker RW, Blom AW, Whitehouse MR, et al. (2019) How long does a hip replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. Lancet 393(10172): 647-654.

- Duwelius PJ, Southgate RD, Crutcher JP, et al. (2023) Registry Data Show Complication Rates and Cost in Revision Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 38(7): S29-S33.

- Goldman AH, Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT, Lewallen DG, Berry DJ, et al. (2019) The Lawrence D Dorr Surgical Techniques & Technologies Award: Why Are Contemporary Revision Total Hip Arthroplasties Failing? An Analysis of 2500 Cases. J Arthroplasty 34(7): S11-S16.

- Deere K, Whitehouse MR, Kunutsor SK, Sayers A, Mason J, et al. (2022) How long do revised and multiply revised hip replacements last? A retrospective observational study of the National Joint Registry. Lancet Rheumatol 4(7): e468-e479.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2024) World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results (UN DESA/POP/2024/TR/NO. 9).

- Harris WH (1969) Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 51(4): 737-755.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5): 373-383.

- Paprosky WG, Perona PG, Lawrence JM (19694) Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 9(1): 33-44.

- Provisional Measure Number 1.021 (Federal Government of Brazil) (2020).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) (n.d.) Population overview of the State of Santa Catarina. Population analysis.

- (2024) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE).

- Atlas of Human Development in Brazil (2021) Ranking.

- Jennison T, MacGregor A, Goldberg A (2023) Hip arthroplasty practice across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) over the last decade. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 105(7): 645-652.

- OECD (2020) Waiting Times for Health Services: Next in Line.

- Gomes LSM, Roos MV, Takata ET, et al. (2017) Advantages and limitations of national arthroplasty registries. The need for multicenter registries: the Rempro-SBQ. Rev Bras Ortop Engl Ed 52: 3-13.

- (2024) International Society of Arthroplasty Registries (ISAR).

- The Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register (DHR) (2021) (B) National Annual Report.

- Lee KH, Chang WL, Tsai SW, Chen CF, Wu PK, et al. (2023) The impact of Charlson Comorbidity Index on surgical complications and reoperations following simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Sci Rep 13(1): 6155.

- Kjørholt KE, Kristensen NR, Prieto-Alhambra D, Johnsen SP, Pedersen AB (2019) Increased risk of mortality after postoperative infection in hip fracture patients. Bone 127: 563-570.

- Guimarães RP, Yonamine AM, Faria CEN, Rudelli M (2016) Is the size of the acetabular bone lesion a predictive factor for failure in revisions of total hip arthroplasty using an impacted allograft? Rev Bras Ortop Engl Ed 51(4): 412-417.

- Telleria JJM, Gee AO (2013) Classifications In Brief: Paprosky Classification of Acetabular Bone Loss. Clin Orthop 471(11): 3725-3730.

- Bohm ER (2009) Employment status and personal characteristics in patients awaiting hip-replacement surgery. Can J Surg J Can Chir 52(2): 142-146.

- Yao JJ, Hevesi M, Visscher SL, et al. (2021) Direct Inpatient Medical Costs of Operative Treatment of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Infections Are Twofold Higher Than Those of Aseptic Revisions. J Bone Jt Surg 103(4): 312-318.

- Ministerio Da Saude (2024) Governo Do Brasil.

- Rasmussen MB, El-Galaly A, Daugberg L, Nielsen PT, Jakobsen T (2022) Projection of primary and revision hip arthroplasty surgery in Denmark from 2020 to 2050. Acta Orthop 93: 849-853.