Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Osteoporosis Screening using Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

Lauren Hisatomi1,2*, Alex Villegas1*, Micaela White1, Dagoberto Pina1, Alec Garfinkel2, Garima Agrawal3, Nisha Punatar3, Barton Wise1,3, Polly Teng3, Hai Le1 and Fragility Fracture Force

1Deparment of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, California, USA

2California Northstate University, College of Medicine, Elk Grove, California, USA

3Deparment of Internal Medicine, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, California, USA

Submission: November 11, 2022; Published: December 01, 2022

*Corresponding author: Lauren Hisatomi, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, California, USA & California Northstate University, College of Medicine, Elk Grove, California, USA & Alex Villegas, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, California, USA

How to cite this article: Lauren H, Alex V, Micaela W, Dagoberto P, Alec G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Osteoporosis Screening using Dual- Energy X-ray Absorptiometry. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2022; 20(5): 556048. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2022.20.556048

Abstract

Purpose: Several survey studies have expressed concerns regarding a general decline in osteoporosis screening as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. We compared our institution’s experience on osteoporosis screening using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Patients ≥50 years who received DXA screening between March 1, 2018 to January 31, 2020 (pre-pandemic cohort) were compared to patients with DXA completed between March 1, 2020 to January 31, 2022 (pandemic cohort).

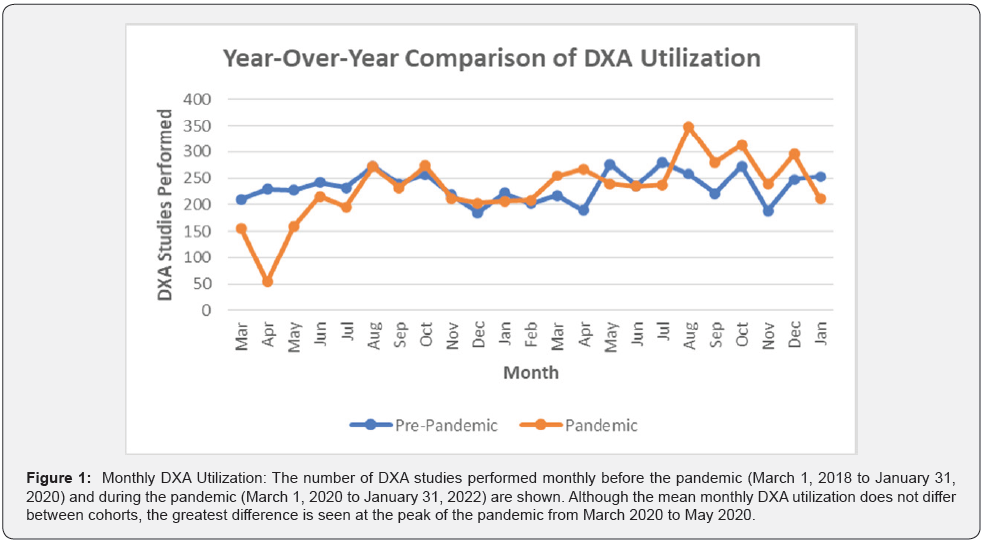

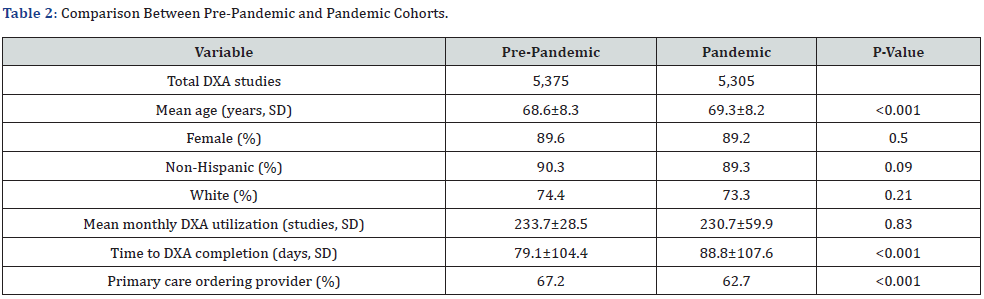

Results: In total, 10,680 DXA studies were completed at our institution over the study period. From March 1 2018, to January 31, 2020, 5,375 DXA studies were completed (pre-pandemic cohort). From March 1 2020, to January 31, 2022, 5,305 DXA studies were completed (pandemic cohort). Mean monthly DXA utilization did not differ between cohorts (233.7±28.5 vs 230.7±59.9 studies, p=0.83).

Conclusion: In our retrospective study, we found that DXA utilization to screen for osteoporosis was not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, DXA completion was more delayed, and the ordering providers were more likely to be non-primary care providers.

Keywords: Osteoporosis; Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA); COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a debilitating metabolic bone disease that accounts for approximately 51% and 24% of hospitalizations for fractures in women and men, respectively [1]. Osteoporosis and osteoporotic-related fractures often negatively affect a person’s quality of life by making it more difficult for the individual to participate in daily routine activities. Over time, some patients may lose function and independence. It is estimated that the number of fragility fractures and the cost of care due to osteoporosis will double in the next fifty years as the population ages [1]. Osteoporosis manifests as decreased bone mineral density (BMD) through the deterioration of bone tissue over time. Patients with osteoporosis are often asymptomatic, which is why it is sometimes referred to as the “silent disease” [2].

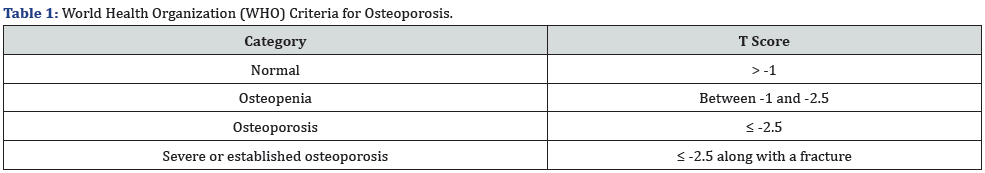

Several tools are used to screen for osteoporosis, but the gold standard remains screening with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). DXA is used to determine BMD, an indicator of bone health and a predictor of fracture risk. These x-rays are usually taken in the hip and spine, and data are reported in the form of Z or T scores [3]. Test results are then compared to a standardized set of established references organized by age, sex, and ethnicity [4]. Osteoporosis is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a T score ≤-2.5 on DXA (Table 1) [5]. Given the economic and healthcare burden of osteoporosis, many organizations recommend timely bone health evaluation for patients with risk factors for osteoporosis such as advanced age, previous fracture, and maternal history of hip fracture [6,7]. Despite having safe and effective screening and treatment for osteoporosis, this metabolic bone disease remains underdiagnosed and undertreated worldwide [8-13].

The COVID-19 pandemic has only made it more difficult for patients to receive appropriate osteoporosis care [14]. During various phases of the pandemic, healthcare facilities have limited their in-person visits to minimize the spread of SARSCoV- 2 infection. Some institutions temporarily closed bone density centers during the early months of COVID-19 as others transitioned to virtual clinic visits only [14]. Overall, studies have shown that osteoporosis screening procedures have drastically declined during the pandemic [14]. For this reason, it was imperative for us to look at our institution’s experience to confirm whether DXA screening has declined during the COVID-19 pandemic in comparison to pre-pandemic. This study aims to determine if there was a decline in osteoporosis screening due to the COVID-19 pandemic at UC Davis Medical Center, which is based in Sacramento, California and serves 33 counties spanning a 65,000-square-mile area. UC Davis has a large patient population as it admits approximately 30,000 patients per year with more than 800,000 visits. In investigating osteoporosis screening, we hope to continue to bring awareness about this condition that is often undiagnosed and undertreated, has substantial financial consequences on our healthcare system, and reduces the quality of life of our patients. We hypothesize that there has been a decline in the use of DXA for osteoporosis screening during the pandemic.

Methods

Patients ≥50 years who received DXA screening at our academic institution were included. Patients with DXA completed between March 1, 2018 to January 31, 2020 (pre-pandemic cohort) were compared to patients with DXA completed between March 1, 2020 to January 31, 2022 (pandemic cohort). Basic demographics including age, gender, race, and ethnicity were evaluated. DXA utilization was calculated as the number of DXA studies completed monthly. The ordering providers (primary care vs specialty care providers) and mean time from initial order to DXA completion were compared between cohorts. Chi square tests were performed for categorical data, while independent t-tests were performed for continuous data, with significance set at 0.05. This retrospective study received IRB approval from the UCD Institutional Review Board and waived requirements for informed consent.

Results

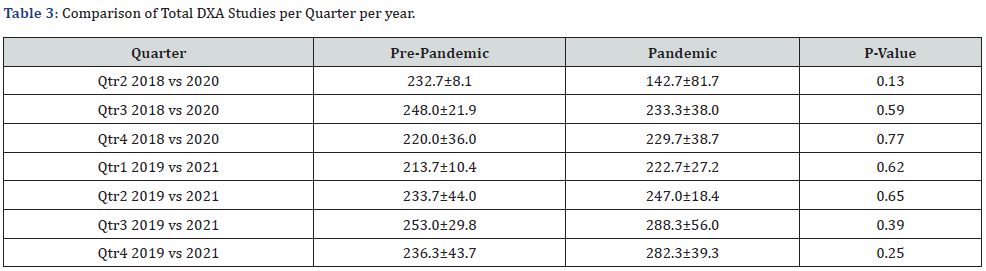

In total, 10,680 DXA studies were completed at our institution over the study period (Table 2). From March 1, 2018 to January 31, 2020, 5,375 DXA studies were completed (pre-pandemic cohort). From March 1, 2020 to January 31, 2022, 5,305 DXA studies were completed (pandemic cohort). Mean monthly DXA utilization did not differ between cohorts (233.7±28.5 vs 230.7±59.9 studies, p=0.83) (Figure 1). There were also no statistically significant differences when comparing total DXA procedures per quarter per year between cohorts (Table 3). Patients were older in the pandemic cohort at the time of DXA completion 68.6±8.3 vs 69.3±8.2 years, p<0.001). The distributions for gender (89.6% vs 89.2% female, p=0.5), ethnicity (90.3% vs 89.3% non-Hispanic, p=0.09), and race (74.4% vs 73.3% White, p=0.21) did not differ between cohorts. The mean time from initial order to DXA completion was shorter for the pre-pandemic cohort (79.1±104.4 vs 88.8±107.6 days, p<0.001). The ordering providers (67.2% vs 62.7% primary care providers, p<0.001) also differed.

Discussion

Our study did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in DXA utilization between the pre-pandemic and pandemic cohorts. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic did not significantly affect osteoporosis screening at our institution. This is in contrast to recent studies published in the United States and other countries. For example, Peeters et al (2021) determined that DXA screening declined during the pandemic in the Netherlands [15]. Similarly, Fuggle et al. (2021) found that during the pandemic, only 29% of patients globally were able to obtain DXA as recommended [16]. However, both were survey studies administered to healthcare professionals who provide osteoporosis care rather than quantitative assessment of the number of DXA studies being performed.

A quantitative analysis of DXA utilization in a Northern Italy orthopaedic hospital documented a nearly 50% decline in DXA examinations from January to May 2020 in comparison to January to May 2019 [17]. This drastic decline was due to complete cessation of DXA studies performed at that institution in April 2020 due to the pandemic. The authors noted a slow return of DXA utilization when DXA studies resumed in May 2020. Similarly, Cromer et al (2021) noted that their Bone Density Center in Boston, Massachusetts closed from mid-March to early June 2020, resulting in a 40% decline in DXA studies during the pandemic [14]. Similar findings were reported in Norway and Dubai [18,19]. Unlike the previous studies, there was no complete cessation of DXA studies at our institution. Therefore, while there was a sharp decline of DXA studies in April 2020 (54 studies) compared to April 2019 (229 studies), DXA utilization quickly normalized, and we could not identify statistically significant differences in mean monthly DXA utilization or DXA utilization per quarter per year between cohorts. Other than April 2020, there was no additional significant decline in DXA utilization during subsequent waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study is the first to evaluate age at time of DXA completion, time from initial order to completion of DXA study, and prescriber ordering the DXA study between the cohorts. We found that patients were older at the time of DXA completion during the pandemic. On average, during the pandemic, patients had to wait 10 days longer to receive their DXA study. We hypothesize that this could be due to the six-week transition to telehealth by UC Davis Health during the peak of the pandemic (March and April of 2020). Our institution saw a 5000% increase in telehealth visits, amounting to 1,000 patients per day within two weeks. This could have then caused the decline in DXA procedures performed in April 2020 due to temporary cessation of in-person clinic visits, leading to radiology imaging delay affecting patients whose studies were ordered after April 2020. Additionally, our results indicate that the percentage of DXA scans ordered by specialists increased during the pandemic. Huston et al. (2020) demonstrated that non-COVID-19 primary care services decreased because of clinics prioritizing the pandemic. This led to primary care clinic closures and a decrease in medical resources [20]. It can therefore be postulated that primary care clinics had less capacity to address patients with non-COVID-19 conditions, such as osteoporosis, as they were focused on treating COVID-19 patients and providing vaccinations.

Our study highlights several findings that are consistent with prior osteoporosis research. In particular, both the pre-pandemic and pandemic cohorts exhibited a much higher female distribution. There is a gender disparity in osteoporosis screening, where women are screened more often than men. Although women are at greater risk for osteoporosis, one study demonstrated that in addition to being under-screened, men have a greater risk for secondary osteoporosis and hip fracture [21]. In terms of race and ethnicity, our results showed a greater predominance of Non-Hispanic and White patients who underwent DXA screening. Similarly, studies have demonstrated that Non-Hispanic Black women are the least likely to obtain osteoporosis screening [22]. These findings emphasize the need to improve access and equity with regard to osteoporosis care for all patients.

Our study has several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, our study population was limited as it was from a single academic institution. Each healthcare organization, county, state, and country had varying degrees of COVID-19 severity, restrictions, and availability of resources. UC Davis Health is a tertiary referral hospital and has ample resources, helping mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and potentially explaining why a decline in DXA screening orders was not observed. For instance, UC Davis Health assembled a team in January 2020 to assist with COVID-19 identification, case management and faculty also assisted in creating guidelines for patient care. Therefore, the impact of COVID-19 on DXA use most likely differs by location and therefore results from this study are not generalizable to other institutions. Furthermore, confounding variables outside of COVID-19 may have influenced DXA utilization and timing to DXA completion. Finally, this study only evaluated osteoporosis screening and not how the pandemic affected osteoporosis treatment and outcomes.

What can we take away from this pandemic regarding osteoporosis care? In any health crisis, as urgent services become prioritized, management of chronic diseases such as osteoporosis may be interrupted. Facility constraints and closures can reduce the opportunity for patients to complete their DXA study in a timely manner, thus potentially delaying osteoporosis treatment. This makes matters worse for a disease that is already underdiagnosed and undertreated. Other studies have shown that complete cessation of osteoporosis care during the pandemic will lead to significant reduction of DXA utilization and a slow return to normalcy. However, as evidenced in our study, maintaining access to DXA screening during the pandemic will result in only a temporary reduction of DXA utilization with a rapid return to normal DXA utilization thereafter. This is the first study to quantitatively compare the rates of osteoporosis screening before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In our retrospective study, we found that DXA utilization to screen for osteoporosis was not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, DXA completion was more delayed, and the ordering providers were more likely to be non-primary care providers.

Statements and Declarations

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Conflict of Interest

Lauren Hisatomi, Alex Villegas, Micaela White, Dagoberto Pina, Alec Garfinkel, Dr. Garima Agrawal, Dr. Nisha Punatar, Dr. Barton Wise, Dr. Polly Teng, and Dr. Hai Le declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Atik OS, Gunal I, Korkusuz F (2006) Burden of osteoporosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 443: 19-24.

- Liscum B (1992) Osteoporosis: the silent disease. Orthop Nurs 11(4): 21-25.

- Lupsa BC, Insogna K (2015) Bone Health and Osteoporosis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 44(3): 517-530.

- Hain SF (2006) DXA scanning for osteoporosis. Clin Med (Lond) 6(3): 254-258.

- Kanis JA on behalf of the World Health Organization Scientific Group (2008) Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical Report. WHO Collaborating Centre, University of Sheffield, UK.

- Force USPST, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Douglas K Owens, Michael J Barry, et al. (2018) Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 319(24): 2521-2531.

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, E M Lewiecki, B Tanner, et al. (2014) Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10): 2359-2381.

- Haffner MR, Delman CM, Wick JB, Gloria Han, Rolando F Roberto, et al. (2021) Osteoporosis Is Undertreated After Low-energy Vertebral Compression Fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 29(17): 741-747.

- Rozental TD, Makhni EC, Day CS, Bouxsein ML (2008) Improving evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis following distal radial fractures. A prospective randomized intervention. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90(5): 953-961.

- Barton DW, Behrend CJ, Carmouche JJ (2019) Rates of osteoporosis screening and treatment following vertebral fracture. Spine J 19(3): 411-417.

- Hooven F, Gehlbach SH, Pekow P, Bertone E, Benjamin E (2005) Follow-up treatment for osteoporosis after fracture. Osteoporos Int 16(3): 296-301.

- Schurink M, Hegeman JH, Kreeftenberg HG, Ten duis HJ (2007) Follow-up for osteoporosis in older patients three years after a fracture. Neth J Med 65(2): 71-74.

- Simonelli C, Chen YT, Morancey J, Lewis AF, Abbott TA (2003) Evaluation and management of osteoporosis following hospitalization for low-impact fracture. J Gen Intern Med 18(1): 17-22.

- Cromer SJ, Yu EW (2021) Challenges and Opportunities for Osteoporosis Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 106(12): e4795-e4808.

- Peeters JJM, van den Berg P, van den Bergh JP, Marielle H Emmelot-Vonk, Gijs de Klerket, et al. (2021) Osteoporosis care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands: A national survey. Arch Osteoporos 16(1): 11.

- Fuggle NR, Singer A, Gill C, A Patel, A Medeiros, et al. (2021) How has COVID-19 affected the treatment of osteoporosis? An IOF-NOF-ESCEO global survey. Osteoporos Int 32(4): 611-617.

- Messina C, Buzzoni AC, Gitto S, Almolla J, Albano D, et al. (2021) Disruption of bone densitometry practice in a Northern Italy Orthopedic Hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Osteoporos Int 32(1): 199-203.

- Hofmann B, Anderson, ER Kjelle E (2021) What Can We Learn From the SARS-COV-2 Pandemic About the Value of Specific Radiological Examinations? BMC Health Serv Res 21(1): 1158.

- Alshaali A, Elaziz SA, Aljaziri A, Farid T, Sobhy M (2022) Preventive Steps Implemented on Geriatric Services in the Primary Care Centers During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Public Health Res 11(2): 2593.

- Huston P, Campbell J, Russell G, Goodyear-Smith F, Phillips Jr R L, et al. (2020) COVID-19 and Primary Care in Six Countries. BJGP Open 4(4): bjgpopen20X101128.

- De Martinis M, Sirufo M, Polsinelli M, Placidi G, Di Silvestre D, et al. (2021) Differences in Osteoporosis: A Single-Center Observational Study. World J Mens Health 39(4): 750-759.

- Noel S, Santos M, Wright N (2021) Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Bone Health and Outcomes in the United States. J Bone Miner Res 36(10): 1881-1905.