Non-Leukemic Femoral Myeloid Sarcoma: An Uncommon Finding Evolving from A Polycythemia Vera

LSR Resende1*, FX Jerves2, MJJ Torres3, FG Faustino1, MAC Domingues4 and L Niero-Melo1

1Hematology Service of Internal Medicine Department, Brazil

2Internal Medicine Residency Program, Morristown Medical Center, Morristown, NJ, USA

3Internal Medicine, Cuenca, Azuay, Ecuador, Cuenca

4Department of Pathology, Botucatu Medical School, Sao Paulo State University - UNESP, Botucatu, SP, Brazil

Submission: October 14, 2021; Published: October 26, 2021

*Corresponding author: LSR Resende, Hematology Service, Department of Internal Medicine, Botucatu Medical School, Sao Paulo State University – UNESP 18618-687, Botucatu – SP, Brazil

How to cite this article: LSR Resende, FX Jerves, MJJ Torres, FG Faustino, MAC Domingues, et al. Non-Leukemic Femoral Myeloid Sarcoma: An 002 Uncommon Finding Evolving from A Polycythemia Vera. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2021; 19(3): 556013. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2021.19.556013

Abstract

Background: Myeloid sarcomas (MS) may present at any site in the body and at any time regarding diagnoses of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndrome or chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. Although, in the subset of chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms they are mostly found in chronic myeloid leukemia and are especially uncommon evolving from an underlying polycythemia vera (PV).

Objective: To describe an uncommon case of non-leukemic MS which evolved in a patient with underlying PV.

Case Report: A 64-year-old Caucasian male presenting a current PV was diagnosed with a destructive tumor mass proximally in his left femur. CD45 immunohistochemistry was the only positive marker in the mass biopsy specimen demonstrating its hematological origin. There was none acute leukemic transformation in his bone marrow at that time, and diagnosis was defined as an MS evolving from the underlying PV. The patient was treated with several AML-based chemotherapy regimens with no improvement. Only local irradiation provided mild clinical response for a while. Side effects combined with poor clinical response did not allow other intensive treatments and the patient died 20 months later under palliative care. During end-stage disease he experienced massive local MS invasiveness but bone marrow leukemization never occurred.

Discussion: Non-leukemicMS are rarely seen as evolution of underlying PV. Diagnosis of this type of isolated tumor is always challenging given that it may be confused with other tumors. Despite using a broad immunohistochemistry panel on his tumor biopsy specimen, MS diagnosis was only possible based on 3 characteristics: fast-growing tumor mass appearing in a patient with underlying PV; cell morphology matching monocyte lineage on H&E stain; tumor cell positivity for CD45. According to literature, the studied patient MS partially responded to radiotherapy but not to systemic AML-based chemotherapy protocols, being his death determined by the end-stage local tumor growing and invasiveness under palliative care.

Conclusion: A rare case of non-leukemic MS was described which was uncommonly seen evolving from a PV; anatomical site was also unusual. The authors highlighted the challenge of MS diagnosis reinforcing that along with immunohistochemistry, tumor histologic features and patient clinical context may be crucial in differentiating a non-leukemic MS from other tumors.

Keywords: Myeloid sarcoma; Non-leukemic;Polycythemia vera; Immunohistochemistry

Abbreviations: MS: Myeloid Sarcoma; AML: Acute Myeloid Leukemia; PV: Polycythemia Vera; CD: Cluster of Differentiation; WHO: World Health Organization; JAK2: Janus Kinase 2; JAK2 V617F: V617F Mutation in the Gene JAK2; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Image; H&E: Hematoxylin-Eosin Stain; TdT: Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase; HD-araC: High-dose Cytarabine; ICE: Ifosfamide + Carboplatin + Etoposide; CVP: Cyclophosphamide + Vincristine + Prednisone; LCA: Leucocyte Common Antigen; B: B Lymphocytes; T: T Lymphocytes; NK: Natural Killer Lymphocytes

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), myeloid sarcoma (MS) is a tumor mass consisting of myeloid blasts with or without maturation occurring in sites other than the bone marrow which affects respective tissue architectures [1]. It is a rare finding that may present at any site in the body and at any time regarding a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes or chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms [2]. In the set of chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms only about 10% of polycythemia vera (PV) patients may evolve into an acute leukemic transformation [3], and the occurrence of non-leukemic MS is rarer still [4-6]. We report a case of a previously diagnosed PV patient who presented an MS proximally in his left femur without showing any bone marrow leukemization. As far as we know, this is the first report of a non-leukemic MS in this anatomical site evolving from underlying PV disease [7]. Besides, the MS diagnosis challenges was highlighted by the authors who reinforced that beyond the immunohistochemistry profile, tumor histological features along with patient’s clinical context may be crucial to differentiate between non-leukemic MS and other tumors.

Objective

Objective: To describe a rare case of non-leukemic femoral MS evolving from underlying PV disease.

Case Report

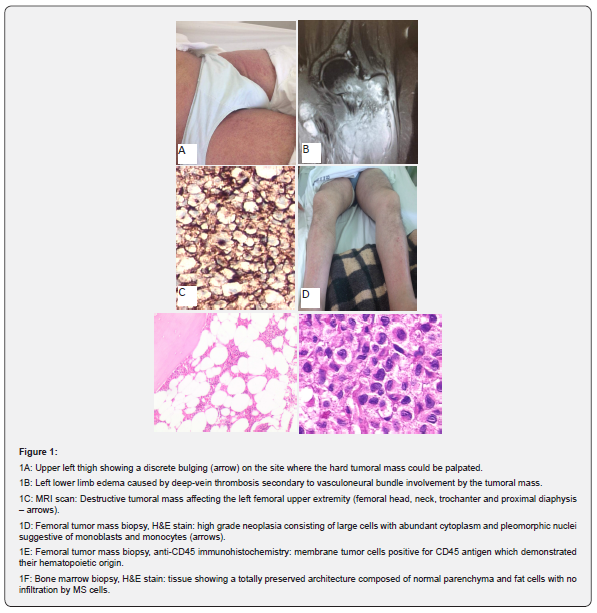

After having 2 acute myocardial infarctions (AMI) plus a transitory ischemic attack (TIA) within the previous 8 years, a 64-year-old Caucasian male was diagnosed with a PV according to 2016 Revised WHO Diagnostic Criteria for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms [7], by showing the following laboratory tests: hemoglobin and hematocrit of 18.7g/dL and 58% respectively, bone marrow tri-lineage proliferation with pleomorphic mature megakaryocytes, presence of JAK2 V617F mutation, and serum erythropoietin level < 1.0mU/mL. Since he had high-risk PV (age > 60 years with JAK2 mutation; clinical history of AMI and TIA), the hematology team initiated a treatment regimen with hydroxyurea plus a daily aspirin. Three months later he was again admitted showing a 10cm diameter fast-growing hard mass in his left thigh close to the groin (Figure 1A). He could not walk due to local pain and swelling affecting the whole lower left limb (Figure 1B). Venous doppler ultrasound showed deep thrombosis affecting both femoral and peroneal left-side veins. Sequential magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a bone destructive tumor mass proximally in the left femur which was infiltrating surrounding soft tissues and the vasculoneural bundle (Figure 1C). Tumor mass biopsy stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) showed a high-grade neoplasia consisting of large cells with abundant cytoplasm and pleomorphic nuclei suggesting monocyte lineage (Figure 1D). The immunohistochemistry panel revealed CD45 as the only positive marker (Figure 1E) with all the following markers being negative: MPO, lysozyme, TdT, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD15, CD20, CD30, CD56, CD68, CD117, CD138, CD163, ALK, fascin, S-100, AE1/AE3.

Kappa and lambda marker results were inconclusive. Final tumor mass diagnosis was MS of monocyte lineage based on its morphology and emergence from an underlying PV. A bone marrow biopsy ruled out any acute leukemic infiltration (Figure 1F). Expecting the patient to develop severe thrombocytopenia during further intensive chemotherapy for MS (7 + 3 AML-based protocol with cytarabine plus idarubicin), an inferior vena cava filter was promptly placed. In total, the patient received 1 cycle of 7 + 3, 1 cycle of HD-araC, and 2 cycles of ICE with no subsequent mass reduction. Thus, local radiotherapy led to pain reduction and lower left limb edema improvement, allowing him to walk again with a walker. While undergoing these treatments, warfarin was only introduced when platelet count was above 30 x 103/mm3. As the patient had suffered repeated episodes of high-risk febrile neutropenia, he was directed to palliative care receiving only oral CVP cycles. After 1 year of palliative care the tumor mass grew quickly, infiltrated overlying skin, becoming ulcerated and infected. At admission, a new skin biopsy showed the same histological and immunohistochemistry pattern as observed in the previous underlying mass specimen. Similarly, less than 5% of myeloblasts were seen in a new bone marrow sample which means there was no MS leukemization. Considering the patient was in very bad shape, he was discharged according to family wishes, and died at home 1 week later. The time between the MS diagnosis and death was 20 months.

Discussion

MS is a broad designation that includes uncommon extramedullary tumors consisting of immature myeloid cells such as myeloblasts, monoblasts, and myelomonocytes [8]. As they show a predominantly granulocytic or monocytic differentiation they are respectively called granulocytic sarcoma and monoblastic sarcoma [9]. MS precede or simultaneously occur with AML although they also have been described in patients with underlying myelodysplastic syndromes or chronic myeloproliferative neoplasias [10,11], which usually means a further transformation of these latter disorders into an AML [12] that may occur over a variable time span [11]. If isolated in an extramedullary site, MS are also known as de novo, primary or non-leukemic [12], which means concurrent leukemization has not occurred until that point. MS most commonly affects skin, soft tissues, the gastrointestinal tract, lymph nodes, or bones [10,11].

Regarding chronic myeloproliferative neoplasias, MS mostly occur in a chronic myeloid leukemia setting, usually preceding or co-occurring with its blast crisis [12]. With respect to PV only about 10% of patients evolve into an AML within 20 years of follow-up [3]. The occurrence of a non-leukemic MS is even more uncommonly seen as result of a PV progression [4-6]. Our patient showed this last rarer clinical presentation.

Non-leukemic MS can be histologically confused with other tumors such as ‘small blue round cell tumors’, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, melanoma and poorly differentiated carcinomas [8] which make their diagnosis challenging [9-11]. It is recommended to use a broad panel of monoclonal antibodies during a non-leukemic MS investigation [8]. Despite taking this approach, most tested antigens in our patient biopsy were negative. The most common non-hematopoietic neoplasias were excluded by immunohistochemistry. In fact, CD45 was the only positive antigen. Formerly called leucocyte common antigen (LCA), CD45 is an evolutionary highly conserved receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase exclusively expressed on all nucleated cells of the hematopoietic system [13]. So, it is possible to state that our patient tumor mass was of hematopoietic origin. The other used antibodies, however, failed to demonstrate to which hematopoietic lineage those cells belonged, given that markers for myeloid cells, lymphoblasts, B, T and NK lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and for some lymphomas were all negative. Although the biopsy cells showed a clear monocytoid morphology, the CD68 marker was also negative on the sample. CD68 is a lysosomal/endosomal-associated type I transmembrane glycoprotein peptide that generally is highly expressed on mononuclear monocyte/macrophage lineage cells [11,14]. Thus, MS could only be diagnosed based on three characteristics: a fast-growing tumor mass appearing in a patient with underlying PV; cell morphology matching monocyte lineage on H&E stain; tumor cells positive for CD45. Shallis et al. (2020) assert that if correct histologic features and clinical context are observed, a diagnosis of MS can still be made if other non-hematological tumors are ruled out [14]. This was how our patient MS was diagnosed.

The pathophysiology of MS is still poorly understood, however, altered homing mechanisms for myeloid lineage blasts have been suggested. MS blasts showing aberrant expression of receptors for chemokines involved in tumor cell interactions with endothelial cells or extracellular matrix may infiltrate organs distant from bone marrow [15].

The best therapy for MS is unclear. Mostly patients receive any form of systemic chemotherapy although critical therapy analysis is complicated by patient- and disease-specific factors [14]. These tumors appear to be highly sensitive to radiotherapy which provides palliation for local symptoms in up to 90% of patients [14]. As our patient showed no improvement with systemic AML-based chemotherapy protocols, his MS was irradiated giving him the most comfortable time since diagnosis. However, poor clinical response combined with his age and the comorbidities triggered by PV plus MS no longer allowed the specific treatment to continue with the patient being directed to palliative treatment until death. Despite a local invasiveness due to the end-stage tumor growth, there was never any bone marrow infiltration by the MS.

Conclusion

We describe a rare case of femoral non-leukemic MS evolving from a PV. Besides being uncommon itself, a non-leukemic MS is rarer still when arising from an underlying PV. It also seems that femoral MS has never been described in a PV patient. The challenges of MS diagnosis were also highlighted in this paper and the authors reinforced that along with immunohistochemistry, tumor histologic features and patient clinical context may be as crucial for differentiating a non-leukemic MS from non-hematopoietic tumors as in determining to which hematopoietic lineage the tumor cells belong.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Botucatu Medical School.

References

- Pilleri SA, Orazi A, Falini B (2017) Myeloid Sarcoma In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al (eds). WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th rev ed. Lyon: IARC pp. 167-168.

- Magdy M, Karim NA, Eldessouki I, Gaber O, Rahouma M, et al. (2019) Myeloid Sarcoma. Oncol Res Treat 42: 219-224.

- Tefferi A (2015) CME Information: Polycytemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 90(2): 162-172.

- Seymour PC, Line BR (1996) Bone scan of advanced polycythemia vera with malignant transformation. Clin Nucl Med 21(11): 844-846.

- Pilleri SA, Ascani S, Cox MC, Campidelli C, Bacci F, et al (2006) Myeloid sarcoma: clinico-pathologic, phenotypic and cytogenetic analysis of 92 adult patients. Leukemia 21(2): 340-350.

- Nafil H, Tazi I, Mahmal L (2013) Myeloid Sarcoma Developing in Prexisting Hydroxyurea-Induced Leg Ulcer in a Polycythemia Vera Patient. Case Rep Med 2013: 497593.

- Tefferi A, Barbui T (2016) Polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 92(1): 95-108.

- Kaur V, Swami A, Alapat D, Abdallah AO, Motwani P, et al. (2018) Clinical characteristics, molecular profile and outcomes of myeloid sarcoma: a single institution experience over 13 years. Hematol 23(1): 17-24.

- Klco JM, Welch JS, Nguyen TT, Hurley MY, Kreisel FH, Hassan A, et al. (2011) State of art in myeloid sarcoma. Int J Lab Hematol 33(6): 555-565.

- Yilmaz AF, Saydam G, Sahin F, Baran Y (2013) Granulocytic sarcoma: a systematic review. Am J Blood Res 3(4): 265-270.

- Seifert RP, Bulkeley W, Zhang L, Menes M, Bui MM (2014) A practical approach to diagnose soft tissue myeloid sarcoma preceding or coinciding with acute myeloid leucemia. Ann Diagn Pathol 18(4): 253-260.

- Almond M, Charalampakis M, Ford SJ, Gourevich D, Desai A (2017) Myeloid Sarcoma: Presentation, Diagnosis and Treatment. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 17(5): 263-267.

- Rheinlander A, Schravena B, Bommhardta U (2018) CD45 in human physiology and clinical medicine. Immunol Letters 196: 22-32.

- Shallis RM, Gale RP, Lazarus HM, Roberts KB, Xu ML, et al. (2020) Myeloid sarcoma, chloroma, or extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia tumor: a tale of misnomers, controversy and the unresolved. Blood Rev 47: 100773.

- Faaij CMJM, Willemze AJ, Revesz T, Balzarolo M, Tensen CP, et al. (2010) Chemokine/Chemokine Receptor Interactions in Extramedullary Leukaemia of the Skin in Childhood AML: Differential Roles for CCR2, CCR5, CXCR4 and CXCR7. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55(2): 344–348.