Blistering Distal Dactylitis: A Narrative Review

Mohammad Daher1, Bendy-Lemon Salameh1, Roba Ghossan2, Aren Joe Bizdikian3, Fouad Fayad2* and Sami Roukoz3

1Saint-Joseph University, Faculty of Medicine, Beirut, Lebanon

2Rheumatology department, Saint-Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon; Hotel-Dieu de France Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

3Orthopedics department, Saint-Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon; Hotel-Dieu de France Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

Submission:June 23, 2021; Published: July 02, 2021

*Corresponding author: Fouad Fayad, Department of Rheumatology, Hotel Dieu De France Hospital, Saint Joseph University of Beirut, Alfred Naccache Street, Achrafieh, Beirut, P.O. Box 166830, Lebanon

How to cite this article: M Daher, B L Salameh, R Ghossan, A J Bizdikian, F Fayad, S Roukoz . Blistering Distal Dactylitis: A Narrative Review. Ortho & Rheum Open Access J. 2021; 18(4): 555991. DOI: 10.19080/OROAJ.2021.18.555991

Abstract

Blistering distal dactylitis (BDD) is a localized bacterial infection of fingers characterized by tense fluid-filled bullae. It is mostly found in children. The pathogenesis of BBD is still not clearly elucidated and seems to be multifactorial. The most predominant bacterial agents are Staphylococcus aureus and Group A Streptococcus. The diagnosis is generally based on clinical findings alone but may be confirmed with further testing. Its potential incidence in any age group as well as the presence of multiple differential diagnosis make the diagnostic process more challenging. A review of the literature was conducted to gain a better understanding of this disease and to reduce the discrepancies that surround its diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Blistering distal dactylitis; BDD; Streptococcal infections; Staphylococcal infections

Introduction

Blistering distal dactylitis (BDD) is a localized bacterial infection of the finger that was first described by Hays & Mullard [1]. This rare dermatological disease involves the volar fat pad of the distal phalanx of digits with fingers being more commonly affected than toes. It usually presents as non-tender fluid-filled lesions [2] (Figure 1). The most frequent etiologic agent is Staphylococcus aureus [3]. BDD is a diagnosis that relies on clinical reasoning. Its potential incidence in any age group as well as the presence of multiple differential diagnosis make the diagnostic process more challenging. A review of the literature was conducted to gain a better understanding of this disease and to reduce the discrepancies that surround its diagnosis and management.

Epidemiology

Blistering distal dactylitis (BDD) is commonly seen in children of 2 through 16 years of age [4]. It is of rare occurrence in adults regardless of their immune status and even more so in the elderly population [5]. However, physicians should be vigilant about this disease no matter the age group [6]. Rare cases of BDD have also been seen in children under 24 months of age [7].

Etiology

The pathogenesis of BBD is still not clearly elucidated. When seen in children [8], BDD is primarily caused by group A beta-hemolytic Streptococci [5]. Also, group B beta-hemolytic Streptococci are a possible etiologic factor in this age group [9]. Due to the major burden of group A Streptococcal disease worldwide, it was critical to detect changes in disease distribution using epidemiological surveillance methods. Among several available methods for defining strains, the typing of the M cell surface protein, a major virulence and immunological determinant of group A streptococci, is a universally used method. Interestingly, there were contrasting differences in the M protein gene typing profile known as emm sequencing between low and high-income countries as well as different clinical presentations of group A Streptococcal disease. For instance, emm 1 and 12 have been the most encountered types in invasive infections or scarlet fever occurring in high-income countries [10,11].

Furthermore, Staphylococcus aureus is becoming an increasingly incriminated agent in BBD3 with methicillin resistant strains described in one of the reported cases [12]. While Streptococcus and Staphylococcus-BDD are clinically indistinguishable, Staphylococcus is mostly detected in adults8 and may be associated with multiple blisters and a more extensive disease. In some cases, two different microorganisms may be isolated simultaneously. The most frequent associations include beta-hemolytic Streptococcus with Staphylococcus aureus [13,14], beta-hemolytic Streptococcus with Staphylococcus epidermidis [15] and Staphylococcus aureus with Herpes simplex virus [16]. BDD occurs more commonly in the fingers than in the toes [11,17] with the index and the thumb being the most frequently concerned digits [12]. The predilection for fingers may be partly explained by the theories behind the development of the disease such as the autoinoculation of the fingers due to nose-picking [6], finger sucking (especially in children aged 1 to 3 years old), exploring the mouths of adults, animal bites [14] and anthropophilic transmission [18,19], traumas like abrasions, finger pricks, and burns [5,7], abnormal skin appendages [20], and iatrogenic causes of intravascular inoculation such as forearm injections [21]. BDD may also be caused by undetectable infections of the anus, conjunctiva or the nasopharynx [8].

Clinical Presentation

Patients with BDD usually present with small (10-30mm in diameter), tense and oval bullae on an erythematous base at the level of the fingers or toes. Most patients report trauma or lesions disrupting the skin of the affected digits, such as insect bites, burns, needle pricks or abrasions. These bullae mostly affect the index fingers and thumbs and tend to occur on the volar fat pads of the distal phalanges but may extend dorsally toward the free edge of the nail, or proximally toward the palm of the hand. These lesions are generally non-tender but may progress into erosive lesions. Multiple lesions occur more frequently with Staphylococcus aureus infections. Upon closer examination, a blood-tinged or purulent liquid is generally found. As is the norm with superficial infections of the digits, systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, and weight loss are rarely reported [5,6,8,12,22,23]. When systemic symptoms do occur, a concomitant infection must be eliminated [12].

Even though herpetic whitlow is considered as a differential diagnosis, these two entities have been reported to coexist, potentially complicating the clinical picture [8]. Moreover, one study suggested screening all patients with BDD for perianal streptococcal dermatitis, however this claim was not backed by any reported cases in the literature [8].

The diagnosis is generally based on clinical findings alone but may be confirmed with further testing [5,8,12]. In the case of ruptured bullae, the enclosed liquid may be collected by swabs previously soaked in sterile normal saline. If no liquid is readily available, collection may be obtained by puncture with a needle and syringe. Direct microscopy and gram staining generally reveal polymorphonuclear leukocytes [23] and gram-positive cocci that are either in chains in the case of Streptococcus pyogenes, or in clusters in the case Staphylococcus aureus. If cultures are taken, they should be performed for both Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus and are considered as the gold standard method.

Recently, group A streptococcus rapid antigen testing has been shown to be an effective testing method, with a sensitivity of 93.5%, specificity of 89.7%, and positive and negative predictive values of 84.1% and 86% respectively when compared to bacterial cultures. The study also argued that, when compared to PCR testing, the specificity of rapid testing would increase, since cultures of cases where Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes coinfection had occurred showed negative Streptococcus pyogenes growth probably due to the inhibitive properties of Staphylococcus aureus on the growth of other bacteria in the culture medium. However, caution should be taken when utilizing rapid testing in the setting of BDD, as use of these testing methods outside of pharyngitis remains off-label [11,17,24]. Blood works are generally not performed in cases without systemic symptoms, and when carried out, they tend to come back normal in cases of uncomplicated BDD.

Differential Diagnosis

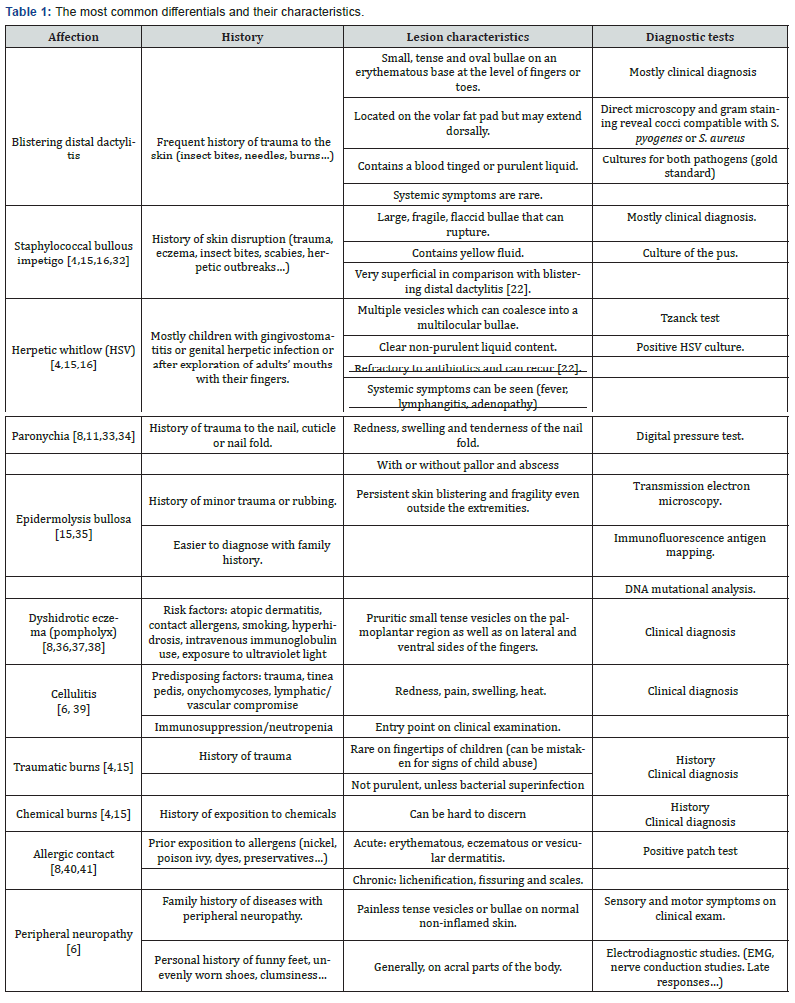

Differential diagnosis for blistering distal dactylitis is relatively broad (Table 1). It mainly includes chemical, thermal or traumatic burns, Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) infections, Staphylococcal bullous impetigo [4,15] (Figure 2) as well as acral psoriasis, insect bites, dyshidrotic eczema (pompholyx) (Figure 3), allergic contact and irritant dermatitis, foreign body reactions and pustular dermatosis of the hands [8]. Vasculitis, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, peripheral neuropathy (with or without thermal injury), peripheral arterial disease and thromboembolism were also mentioned [6]. While both are caused by the same bacteria, bullous impetigo is very superficial in comparison with BDD [25]. HSV infections are characterized by their recurrence [26] and their non-response to antibiotics since they are of viral nature [5]. Both herpetic whitlow and staphylococcal bullous impetigo can be distinguishable by appropriate cultures and smears [15]. In addition, epidermolysis bullosa simplex type Weber-Cockayne should also be considered as a differential diagnosis [15]. While BDD is localized on the distal volar fat pad of fingers and toes and can also extend dorsally to the nail folds [14] it is different from paronychia, which generally involves the skin at the edge of the nail [8,11].

Complications

BDD is rarely complicated and is generally known to subside with proper treatment [22]. Cases of recurrent BDD have been described, and this is especially encountered when the greater toe is affected along with an ingrown nail [25]. A solitary case of osteitis and auto-amputation of the distal phalanx has been reported in a 9-month-old girl with HIV who had not received proper treatment until 2 months after the onset of symptoms [26]. One case of recurrent BDD in an immunocompetent elderly woman was found in the literature and was associated to the concomitant initiation of treatment by amiodarone, an antiarrhythmic drug known to be associated to cutaneous vasculitis. After discontinuation of amiodarone for a period of 2-weeks, the blisters had resolved and treatment with amiodarone reinstated6. No cases of post-streptococcic glomerulonephritis have been reported in the literature [23].

Treatment and follow-up

BDD is classified as an uncomplicated superficial skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI), and if adequately treated, carries a low risk for limb amputation and bacteremia [27]. Choosing an adequate treatment plan depends on the severity of the local infection, the existence of systemic signs and the presence of comorbidities. Treatment of BDD should start with incision and drainage or deflation with a sterile needle of the bullae followed by the application of wet to dry clean gauze on draining wounds and erosions [8]. In most cases, the diagnosis of BBD is solely clinical and does not require extensive tests. Moreover, with the increasingly poignant universal threat of antibiotic resistance and with Staphylococcus aureus becoming the leading bacterial pathogen worldwide [28], a course of empiric B-lactamase-resistant antibiotic should be initiated to cover both Gram-positive causative agents of BBD, according to local resistance patterns. In the absence of systemic signs, treatment can be carried out in the outpatient setting [27,29,30]. Topical antibiotics can be used in very mild cases but are often not sufficient alone. The mainstay of treatment is a systemic course of antibiotics.

Patients should start improving 24 to 48 hours after the initiation of antibiotics and treatment is continued for 7 to 14 days depending on the clinical response. However, patients who do not improve after 48 hours, develop systemic signs or have worsening local symptoms, need to be re-evaluated by sending specimens for culture and susceptibility testing to tailor the antibiotic treatment and assess for potential admittance to the hospital to avoid worrisome outcomes. In most cases, a multidisciplinary approach improves the management of these patients [31].

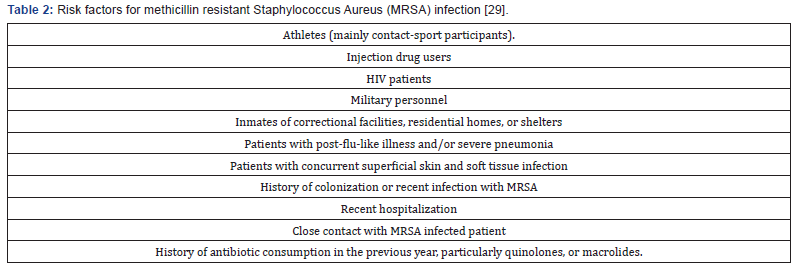

Healthy outpatients do not need systematic empirical coverage for methicillin resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) in the absence of risk factors (Table 2) [29]. Oral agents effective against MRSA in adult patients in the absence of signs of severity include Linezolid, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), and tetracycline (doxycycline or minocycline) among other antibiotics [27]. If coverage of both Streptococci and MRSA is desired in adults for uncomplicated SSTI, oral treatment options include the combination of either TMP-SMX or doxycycline with a B-lactam, clindamycin monotherapy or linezolid as a single agent. Rifampin monotherapy or add-on is not recommended.

In children, tetracyclines are not recommended below eight-years old and Linezolid can be considered starting 12 years of age [30]. In most cases, there were no recurrences [5,7,8] and follow-up was not needed.

Conclusion

BDD is a blistering acral skin and soft tissue infection mostly found in children. The pathogenesis is unclear and seems to be multifactorial. The most frequently isolated pathogens are Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus Aureus. The diagnosis is mainly clinical and does not allow to differentiate between the two pathogens in most cases. Diagnostic tests are not required initially as they have low yield in uncomplicated cases. They are most effective in non-responding or severe cases where they play an important role in tailoring the antibiotic treatment. Patients are treated with incision and drainage of the bullae followed by an empiric antibiotic treatment. Follow-up is not required as most cases are mild and resolve completely after treatment.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Hays GC, Mullard JE (1972) Can nasal bacterial flora be predicted from clinical findings?. Pediatrics 49(4): 596-599.

- Kowtoniuk R, Bednarek R, Maroon M (2018) Blistering Distal Dactylitis. JAMA Dermatol 154(12): 1480.

- Veraldi S, Schianchi R, Nazzaro G, Cambiaghi S. Seven Cases of Blistering Dactylitis. Acta Derm Venereol 100(14): adv00196.

- Benson PM, Solivan G (1987) Group B streptococcal blistering distal dactylitis in an adult diabetic. J Am Acad Dermatol 17(2 Pt 1): 310-311.

- Kollipara R, Downing C, Lee M, Guidry J, Robare-Stout S, Tyring S (2015) Blistering Distal Dactylitis in an Adult. J Cutan Med Surg 19(4): 397-399.

- Hinkamp CA, Shah NH, Holland N, Wright A (2018) Recurrent blistering distal dactylitis due to Staphylococcus aureus in an immunocompetent elderly woman. BMJ Case Rep 2018: bcr2017222772.

- Lyon M, Doehring MC (2004) Blistering distal dactylitis: a case series in children under nine months of age. J Emerg Med 26(4): 421-423.

- Scheinfeld NS (2007) Is blistering distal dactylitis a variant of bullous impetigo?. Clin Exp Dermatol 32(3): 314-316.

- Frieden IJ (1989) Blistering dactylitis caused by group B streptococci. Pediatr Dermatol 6(4): 300-302.

- Steer AC, Law I, Matatolu L, Beall B, Carapetis J (2009) Global emm type distribution of group A streptococci: systematic review and implications for vaccine development. Lancet Infect Dis 9(10): 611-616.

- Jung C, Amhis J, Levy C, Vincent Salabi, Berkani Nacera, et al. (2019) Group A Streptococcal Paronychia and Blistering Distal Dactylitis in Children: Diagnostic Accuracy of a Rapid Diagnostic Test and Efficacy of Antibiotic Treatment. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 9(6): 756-759.

- Fretzayas A, Moustaki M, Tsagris V, Brozou T, Nicolaidou P (2011) MRSA blistering distal dactylitis and review of reported cases. Pediatr Dermatol 28(4): 433-435.

- Zemtsov A, Veitschegger M (1992) Staphylococcus aureus-induced blistering distal dactylitis in an adult immunosuppressed patient. J Am Acad Dermatol 26(5 Pt 1): 784-785.

- Hays GC, Mullard JE (1975) Blistering distal dactylitis: a clinically recognizable streptococcal infection. Pediatrics 56(1): 129-131.

- McCray MK, Esterly NB (1981) Blistering distal dactylitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 5(5): 592-594.

- Ney AC, English JC 3rd, Greer KE (2002) Coexistent infections on a child's distal phalanx: blistering dactylitis and herpetic whitlow. Cutis 69(1): 46-48.

- Cohen R, Levy C, Cohen J, F Corrard, P Deberdt, et al. (2014) Diagnostic des tournioles à streptocoque du groupe A Diagnostic of group A streptococcal blistering distal dactylitis. Arch Pediatr 21 Suppl 2: S93-S96.

- Norcross MC Jr, Mitchell DF (1993) Blistering distal dactylitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Cutis 51(5): 353-354.

- Schneider JA, Parlette HL 3rd (1982) Blistering distal dactylitis: a manifestation of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. Arch Dermatol 118(11): 879-880.

- Wannamaker LW (1970) Differences between streptococcal infections of the throat and of the skin. I N Engl J Med 282(1): 23-31.

- Dauendorffer JN, Amouyal C, Mardare C, Ille O (2009) Staphylococcal blistering distal dactylitis after injections into the forearm]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 136(5) :451-452.

- Woroszylski A, Duran C, Tamayo L, Orozco M, Ruiz-Maldonado R (1996) Staphylococcal blistering dactylitis: report of two patients. Pediatr Dermatol 13(4): 292-293.

- Kliegman R, St Geme J, Blum N, et al. (2019) c. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier Inc, pp. 3549–3559.

- Cohen JF, Cohen R, Bidet P, Corinne Levy, Patrice Deberdt, et al. (2013) Rapid-antigen detection tests for group a streptococcal pharyngitis: revisiting false-positive results using polymerase chain reaction testing. J Pediatr 162(6): 1282-1284.e1.

- Telfer NR, Barth JH, Dawber RP (1989) Recurrent blistering distal dactylitis of the great toe associated with an ingrowing toenail. Clin Exp Dermatol 14(5): 380-381.

- Oyedeji OA, Oluwadiya KS, Aremu AA (2011) Blistering Digital Dactylitis Complicated by Osteomyelitis and Amputation in an HIV-Positive Infant. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 10(5): 280-282.

- Sartelli M, Guirao X, Hardcastle TC (2018) WSES/SIS-E consensus conference: recommendations for the management of skin and soft-tissue infections. World J Emerg Surg 13: 58.

- Reddy PN, Srirama K, Dirisala VR (2017) An Update on Clinical Burden, Diagnostic Tools, and Therapeutic Options of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Dis (Auckl) 10: 1179916117703999.

- Bystritsky R, Chambers H (2020) Cellulitis and Soft Tissue Infections. Ann Intern Med 172(10): 708 Ann Intern Med (2018) 168(3): ITC17-ITC32.

- Larru B, Gerber JS (2014) Cutaneous bacterial infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes in infants and children. Pediatr Clin North Am 61(2): 457-478.

- Cunto ER, Colque ÁM, Herrera MP, Viviana Chediack, Maria Ines Staneloni et al. (2020) Infecciones graves de piel y partes blandas. Puesta al día [Severe skin and soft tissue infections. An update]. Medicina (B Aires) 80(5): 531-540.

- Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G (2014) Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 90(4): 229-235.

- Rerucha CM, Ewing JT, Oppenlander KE, Cowan WC (2019) Acute Hand Infections. Am Fam Physician 99(4): 228-236.

- Burge TS (2004) Removing adhesive retention dressings. Br J Plast Surg 57(1): 93.

- Bardhan A, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Chapple ILC, Jo-David Fine, Natasha Harper, et al. (2020) Epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Rev Dis Primers 6(1): 78.

- Nishizawa A (2016) Dyshidrotic Eczema and Its Relationship to Metal Allergy. Curr Probl Dermatol 51: 80-85.

- Lofgren SM, Warshaw EM (2006) Dyshidrosis: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and therapy. Dermatitis 17(4): 165-181.

- Calle Sarmiento PM, Chango Azanza JJ (2020) Dyshidrotic Eczema: A Common Cause of Palmar Dermatitis. Cureus 12(10): e10839.

- Bailey E, Kroshinsky D (2011) Cellulitis: diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther 24(2): 229-239.

- Esser PR, Martin SF (2017) Pathomechanisms of Contact Sensitization. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 17(12): 83.

- Snyder M, Turrentine JE, Cruz PD Jr (2019) Photocontact Dermatitis and Its Clinical Mimics: an Overview for the Allergist. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 56(1): 32-40.

- Leung AK, Barankin B, Hon KL (2014) Dyshidrotic eczema. Enliven: Pediatr Neonatol Biol 1: 2.